The poet began life in a hidden village by the sea. But then her father became stricter and more suspicious of the corrupting influence of ‘Babylon’ …

We lived by the seaside until I was five years old, in our tiny fishing village called White House, which belonged to the fishermen of my mother’s family, her father and grandfather. Hidden just beyond the margins of the postcard idea of Jamaica was our little community, a modest hamlet shrouded behind a wall of wind-gnarled trees and haphazard cinder blocks, a half mile of hot sand browned from our daily living and sifting between bare toes, glittering 300 yards in every direction to the sea. Here there was no slick advert of a “No Problem” paradise, no welcome daiquiris, no smiling Black butler. This was my Jamaica. Here, time moved slowly, cautiously, and a weatherworn fisherman, grandfather or uncle, may or may not lift a straw hat from his eyes to greet you.

My family lived in close quarters and knew the subtle dialect of each other’s dreams. Under a zinc roof held together with sandy planks and sea-rusted nails, we lived in the shrinking three-bedroom house my grandfather had built with his own hands. I shared one room with my parents and my brother, Lij, who was two years younger than me, all four of us sleeping on the same bed, while my newborn sister, Ife, who was four years younger, slept in a hand-me-down playpen next to us. My aunts Sandra and Audrey shared a room with my cousin, while my grandfather and his girlfriend slept with their three young daughters in their own room. Somewhere in this house, or the next, is where my mother keened her first cry, and my grandmother keened her last.

We had no electricity, no running water. With the windblown houses and ramshackle beach, indoor plumbing was a luxury, so none of the houses in the village had bathrooms. Instead, all the villagers shared a pit-latrine, about 300 yards away from the farthest house. Children were not allowed to use the latrine, since we were in danger of falling in, so we were each tasked to keep a plastic chimmy in the house, emptying it into the sea every morning. My parents washed outside in a communal shower hastily built with thrown-away plywood, while my siblings and I bathed in basins set down close by, next to a standpipe in the yard.

The sea was the first home I knew. Out here, I spent my early childhood in a wild state of happiness, stretched out under the almond trees fed by brine, relishing every fish eye like precious candy, my toes dipped in the sea’s milky lapping. I dug for hermit crabs in the shallow sand, splashed in the wet bank where stingrays buried themselves to cool off.

Each day my joy was a new dress my mother had stitched for me by hand. She and her sisters laughed like happy sirens wherever they went, crashing decibels that alerted the whole village to their gathering. Whenever the sisters sat together on the beach talking, I clung to their ankles and listened, mimicking their feral cackling, which not even the herons overhead could escape. I never loved any place more than this.

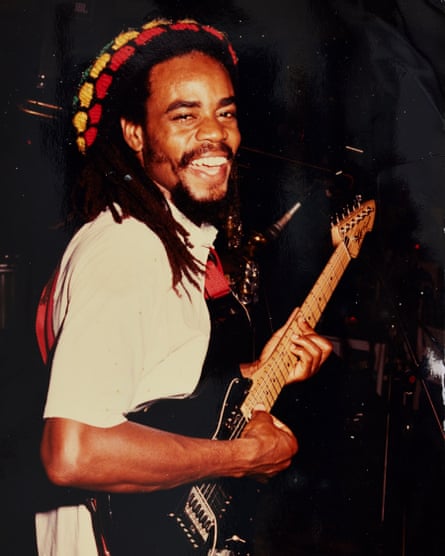

My father was not from the seaside, so he never felt at home at White House. He was a man who lived among fishermen but did not eat fish, adhering in all ways to an ascetic Rasta existence: no drinking, no smoking, no meat or dairy, all tenets of a highly restrictive way of living the Rastafari called Ital. Already, at 26, his thick beard and riverine dreadlocks gave him the wizened look of an augur whose tea leaves only foretold catastrophe. Some days he would bring his guitar to the sand and belt out his reggae songs, forecasting the impending peril of Black people with a stormy austerity that must have seemed misplaced at the seaside.

There was no time for idling with Babylon on the prowl, he would warn, often trapping villagers into long talks about fortifying their minds and bodies against the evils of the western world. “For a weak mind is ripe for the worms of Babylon,” he would caution, slowly sharpening his look into a gaze that could overcloud the sun. A gaze that my siblings and I would later come to know all too well.

Even at this young age I knew that my parents were unusual. They were the only ones at White House who had dreadlocks, and the only people I had ever heard call out the name of Haile Selassie in reverence, though it would be some time before I questioned why. Most days my father journeyed far away to the hotels lining our coast, where he played his reggae music for tourists, his guitar and dreadlocks heavy dreams slung over his back. When he was gone, my pregnant mother spent her few free hours while my baby brother slept scouring the beach for empty conch shells, or chopping mounds of almonds to make a sugary confection called almond drops to sell to tourists, supplementing the family’s income. Before he left for work, my father would always stoop down, hold me eye to eye, and warn me to stay away from the sea. I promised him that I would. As the light grew longer with the passing months, I grew more curious, roaming ever closer to the boundary of the shoreline, away from my mother’s watchful eye, testing how far along our beach I could go.

Firstborn of four, I had claimed this beach as much as it claimed me. As a toddler, I would wade into the shallows to wash my chimmy with my mother, while the steady clamour of Concorde jets shrieked across the sky, their white contrails crisscrossing our blue. Each one an iron bird, a bird of Babylon.

I had grown accustomed to the constant roaring of planes leaving from the airport next door, a place forbidden to us. Next to the airport, looming along the borders of our village, were hotels with high walls made of pink marble and coral stone, flanked on top by broke-glass bottles, their sharp edges catching the light in cruel warning: to live in paradise is to be reminded how little you can afford it. Each new hotel they built was larger than the last, until the resorts resembled our still-standing colonial houses and plantations, many of which served as attractions and wedding destinations for tourists. This was the fantasy tourists wanted to inhabit, sunbathing at hotels along the coast named Royal Plantation or Grand Palladium, then getting married on the grounds where the enslaved had been tortured and killed.

Every year, Black Jamaicans owned less and less of the coastline that bejewelled our island to the outside world, all our beauty bought up by rich hoteliers, or sold off to foreigners by the descendants of white enslavers who earned their fortunes on our backs, and who still own enough of Jamaica today to continue to turn a profit.

But my great-grandfather would not sell our little beachside. He held on to his home, even as the hotels grew grander on both sides of the village, even as we lived deeper and deeper in their shadow, until eventually the coral reefs he fished in blanched and disappeared, his livelihood gone.

Now most of Montego Bay’s coastline is owned by Spanish and British hoteliers – our new colonisation – and most Jamaicans must pay an entrance fee to enter and enjoy a beach. Not us. Today, no stretch of beach in Montego Bay belongs to its Black citizens except for White House. My great-grandfather had left the land title and deed so coiled in coral bone, so swamped under sea kelp and brine, that no hotelier could reach it. This little hidden village by the sea, this beachside, was still ours, only.

The first time I disobeyed my father and walked into the sea alone, I was four years old. The afternoon heat was perishing. My father had already left for work, and my pregnant mother was sweating somewhere out of sight, bathing my baby brother in the same red plastic basin she’d use to handwash our clothes, or bending over to feed her own baby sister, her father’s newest newborn, who she’d delivered from his scared teenage girlfriend on our bedroom floor only a month before. While cooling down under the palms outside in the sand, I spotted something glinting in the water, caught under the sun’s glare. Calling me.

Hello and I love you, said a reedy voice from the sea, speaking the kind language of a small child, and so I stepped in, first one foot in the sinking sand and then another, warm sea-froth snaking around my tiny ankles, then rising quickly to my knees. It didn’t matter to me that I didn’t yet know how to swim. I turned one last time to look at our house – my grandfather’s house – a hundred feet away, crouched small on the sand, sun glimmering off its zinc roof, the ripe almond trees on either side, and saw no one reaching for me, so I threw myself quietly into the rollicking waves.

The seawater rose to my chest, the waves splashing against my torso, my dress clinging frantic to my skin. Saltwater filled my nostrils and mouth as I kicked my arms and legs uselessly, my body sinking in slow motion, my hands reaching up, reaching out, and feeling only sea, touching nothing and nowhere but the darkening blue below.

What I remember next was red. Red shirt, red in the water. Blood.

Suddenly, my mother’s arms were around me, lifting and gasping, and the world unsealed itself and sang every song in my ear. My mother held me tight, too tight, and screamed my name. She sobbed and looked into my face, darted between my eyes, touched my head, counted my fingers, kissed them, and sobbed and sobbed.

“Are you OK?” she cried, breathless. “Are you OK? Are you OK?”

She had flown to me from hundreds of yards away. As she dashed, something in the sand had ripped through her bare foot, a broken bottle or old tin can, and now she bled all over the sand, all over me. She didn’t seem to notice or feel it, as she touched me gently here and there, pleading, “Are you OK?”

“Yes, I’m OK,” I told her, with what my mother has described as an unnatural calm, before I slipped my wrinkled thumb into my mouth and sucked, looking away from the horizon. I placed my head against her heaving chest, relieved to gulp the rush of air, and breathed when she breathed.

She never told my father about my near-drowning, I discovered three decades later. They had both wished for a Rasta family for so long that she could not bear to name the danger we’d only narrowly escaped – danger that my father soon began to foresee in every corner.

Ever since I had known him, my father had the stony demeanour of a general on the eve of a decisive battle, and in my youth I revered him. Though he had a naturally frail frame and was no taller than my mother, he could quiet the whole house just by walking through the door, with an air as perishing as His Majesty’s. Under Haile Selassie’s scorpion-gaze, I was small. His portrait hung high from our living room wall, searing into me whenever my father spoke.

We lived in a noisy tangle with my mother’s family, who my father called baldheads and heathens, the unprincipled men and women of Babylon. Living in the same house meant there was no gate to guard me and my siblings from them, and there were no fences to keep the other villagers away. This troubled him. Steadfastly devoted to Rastafari, my father had a strict binary of rules by which he measured everything. What was righteous and what was wicked. Who was blessed and who was heathen. Though my siblings and I were all under six, the purity of our spirits obsessed him because there was no way for him to know that my “livity” was righteous – that I followed the true path of Rastafari – once I scampered away from the heat of his gaze.

Throughout my life, my father was the main breadwinner in our family, and was always gone to the hotels for work. Six nights a week, he travelled for hours by bus to the resorts, then often stayed overnight, so he was gone when we left for school in the early mornings, and gone again when we came home in the afternoons. There was no other option. Being a musician was just about the only way a Rastaman could be gainfully employed in Jamaica.

By 1989, when we lived at White House, reggae’s promise of cultural revolution and freedom for Black people had waned. Bob Marley had been dead almost a decade, Selassie dead for almost 15 years, and the Rastafari movement had gone back to the fringes of society, with most reggae musicians relegated to performing cabaret shows at the new palatial resorts devouring our northern coastline. Reggae’s original mission of anticolonial rebellion and spreading the message of Rastafari had been defanged. My father was convinced that reggae’s erasure by dancehall in the 1990s was a deliberate ploy by Jamaica’s white rightwing prime minister, Edward Seaga, and the CIA, an agency he believed to be the villainous heart of Babylon itself.

Though my father sang at these hotels to make a living, first and foremost for him, reggae was a religious experience. He believed that if he kept playing his reggae with righteous conviction, this crooked world would wake up and change. If he kept playing, he could save Black people’s minds, and we would reach Zion, the promised land in Africa.

What the tourists couldn’t discern, as they drank and ate dinner while my father sang and flashed his dreadlocks on stage, was his true motivation for singing. Night after night he sang to burn down Babylon, which was them.

after newsletter promotion

At the seaside, we had a small radio but no television, so we got our news of Babylon like roots wine and bitters from my father’s mouth. He was our god of history, god of media, and high priest all in one. Every week my brother, my sister and I kneeled in front of him like disciples as he taught us Black history; all the crucial knowledge that Babylon kept from us, he said. He told us of African kings and conquerors, of unsung Black inventors and pioneers, proof of our glory, our greatness. He wanted us to know we were mighty. Like most members of Rastafari, my father’s most enduring wish was repatriating to Africa, and he sang us psalms of the motherland so we would know ourselves. “Africa for Africans!” was his frequent rallying cry, quoting Marcus Garvey, and we would bellow the words back to him in response, feeling our power.

Whenever the spirit of Jah flowed through him, my father pointed his hands into a sacred Rasta symbol called the sign of the Power of the Trinity, and my brother would follow along, both of them looking regal and militant with their index fingers pointed down into a diamond, like the emperor did above our heads. Once, I tried linking my fingers into the sacred sign as well, but my father firmly peeled my hands apart. He shook his head at me and said: “This is not for you. This is only for bredren.” I crumpled away, wondering why I was unworthy, and let my hands hang limp as a soaked flower.

When he wasn’t exalting the majesty of Selassie, my father would deliver hour-long lectures about the evil white men who ruled and ruined the world, the men he imagined every time he said “Babylon”. He wanted us to guard ourselves from them, to watch out for the bloodsuckers and baldheads. At night in our bedroom he chanted “Fire bun!” at those duppies out to get us, thorned to anger by those he called cattle, those “simple people” with “simple minds”, telling me and my siblings that Jamaicans were enslaved by Christianity, by America, and by that “damn bugu-bugu noise”, which is what he called dancehall.

“These people are in chains and don’t even see it,” he told us. My mother, listening with her sewn-up silence, smoked her spliff and nodded along. If my siblings and I were unable to escape before one of his lectures began, we were forced to sit in the cramped bedroom and listen to it in full, nodding often and bleating out agreement. And yet, loving him was so easy. It was something I’d learned from my mother all too well – there was only one answer to whatever he said. Yes, Daddy. Whatever lecture or conjecture: Yes, Daddy. A keen face of listening, then Yes, to whatever he said. Accepting his bitters like spring water.

When he was feeling particularly loving, he called me Budgie, after his favourite bird, the budgerigar. “Because of how sweetly you used to coo as a baby.” But my interior was volatile, he said. My giddiness was a weakness, which made me susceptible to the wiles of Babylon. I needed discipline. Like most members of Rastafari, my father believed that a person’s body was Jah’s temple, and should remain pure and uncorrupted, just as the mind should remain vigilant against encroaching evil. Inching ever closer was Babylon and its temptation.

It was baldheads who posed the gravest danger to my purity, my father said. A year before, my family had survived Hurricane Gilbert, which came raging from the sea in 1988, destroying our boats and fish traps, demolishing our house, unpeeling the whole roof, and splintering our furniture to dust. But we had survived. It was not the sea or the hungry mangroves that brought down darkness on I and I, but the heathens right here in the village. Chief among Dad’s accursed heathens were my two aunties. Their livity wasn’t right, my father said, denouncing them as Jezebels who wore too much “jingbeng” – dangling gold earrings and bangles, false fingernails and bright red nail polish. They had chemically processed hair and wore makeup and tight jeans shorts. They were pork-eaters and rum-drinkers. They liked dancehall and gossiped about the men they dated. To my father they may as well have been the grand architects of Babylon. Unclean women, he called them, and skirted them with a screwface and his nose in the heavens.

My auntie Audrey pushed back against his rants, sparring nearly every day with my father. When she could no longer endure his lecturing, she rolled her eyes and told him to shut up, pointing towards the road, telling him to “galang back where yuh come from!”

Auntie Audrey, who had known my father long before my mother did, was distressed by my mother’s radical change after meeting my father, and was a frequent and outspoken critic of his control. Despite what my father told me about her, I loved my auntie. She was beautiful and kind and would loom bright as the north star in my sky. Of the entire village, even the men, she was the only person who ever matched his conviction, standing firm to challenge him, which angered him even more. A rebellious woman like her was “an instrument of Babylon”, my father said.

“Yuh brainwash my pretty sister and hide her ’way,” Auntie Audrey yelled one day in an argument with my father. “I saw you kissing up another woman in the back seat of the taxi while my sister sitting there in the front seat listening to the two of you, silent like stooge.” Her voice quavered at the memory. She could not reconcile this voiceless disciple my mother had become. While they quarrelled, my mother took me and my siblings to the sea and stayed out of it.

Iremember my mother in this time as perpetually silent, her lips pursed as if she might never speak another word. She began smoking ganja the way my father played his music – what began as her way to commune with His Majesty soon became a way to escape the daily strife of living in Babylon, and, before long, it became a fixed aspect of her character.

She followed the smoke into a state of calm, and avoided all conflict. At White House she had been pregnant with three children in four years, and was wary of thinking even a single bad thought, lest it affect the child growing inside her. She wanted none of the nasty argument, so she stayed away, and I was grateful for her quiet shelter, the steady tide of her tranquillity.

When the walls between my father and auntie scorched, my father grabbed his guitar and sang a less peaceful song. Back straight as an ancient tree, he jolted pen to paper, and chanted out “Fire bun!” from the depths of his lungs before he strummed his guitar, decrying his hatred for Babylon, baldheads and bloodsuckers at top volume, pouring his lava into song lyrics. In times like these, his reggae music was also his firebomb, a way to obliterate whatever evil corrupted his and Jah-Jah’s green earth.

He closed his eyes and started singing a pleading croon. I stood outside our bedroom window and listened. He was beseeching Jah to destroy all heathens. As he sang, I felt hot coals burning underfoot. The emperor’s black gaze, even out of sight on the living room wall, made my stomach lurch.

When my father was finished singing, I heard his voice rumbling through the bedroom window as he talked to my mother. Gruff and muffled, I picked out the particular tenor he used whenever he talked about unclean women. “Lay down with mongrel, you ketch flea,” he said. “I man daughters cyaan grow wit heathens and idolise their ways.”

My mom shook her head gravely as he spoke, assuring him that would never happen. He had already forbidden me from playing with my cousin and baby aunts because they were too rough and kept bruising me. But he still rustled awake in his hotel room at night, worried about my adult aunts being around me while he was gone.

“All the sistren dem lost now,” my father said, voice hushed. “Lost. Because they fall under the spell of Babylon.” He pulled on his precept and shook his head. “I man tired of living with Jezebel,” he said.

As he spoke, the words blazed against my mind, fear rattling me as my father cursed on, terrified that I, too, would fall under an evil spell of Babylon and get lost.

“This world has no place for an unclean woman,” my father said, and turned to leave my mother in the bedroom.

I scattered out of sight down the beach and found the hull of an empty sea urchin with which to trouble my hands. I was five years old, heart skittering as I sat alone with this thought, hazy and unformed. The unclean woman. It sounded bad, and dirty. It made my father angry. The idea that I could be someone like that frightened me.

Though I was too young to understand that my father believed the sanctity of my soul was at stake, I was petrified of becoming unclean. It was almost a decade before I learned my ruin had been fixed all along. Rasta bredren believed women were more susceptible to moral corruption because they menstruated. I was destined to be unclean. But at five years old, I wanted only to be good for him. I wanted to be worthy. Though I was born a daughter, I still believed I was a salvageable machine; the correct cogs and automation would someday make me right. At night, I imagined Babylon ramming its three-horned beast into my unsoiled interior and then Jah riding in to purify me.

It was Babylon that drove us away from the sea, in the end. The longer we lived with baldheads who didn’t share my father’s beliefs, the worse his distrust of outsiders became. Growing ever more preoccupied with the encroachment of Babylon, he decided we’d outgrown White House. My mother, still shaken by my near-drowning even a year later, agreed.

My father had found us a new place to move, a place free from Babylon’s system, where we didn’t have to “deal with no ism and schism”. About two weeks later, the moving truck arrived in the closed throat of evening. My parents told no one, neither my aunties, nor my grandfather, nor my cousins, that they were moving that night. In less than two hours, we were ready to go. I don’t think I understood the truth of it then – that we wouldn’t ever be coming back.

It was pitch black when we moved away. The houses were barely visible, and the crickets, I remember, were the only things that sounded against our departure. My parents rolled our life up in the small shell of the pickup truck and told the truckman to start driving as if we had never lived at White House at all. I looked back at the seaside as we left, but it was ink dark. All that was visible was the ghost outline of the waves I knew were there, waves I felt watching as the distance grew between me and the sea. I said goodbye to my village of the lonely and unclaimed. The only place I still call home.

Years later, while cloistered in the countryside and aching for my birthplace by the sea, I would come to understand. There was more than one way to be lost, more than one way to be saved. While my mother had saved me from the waves and gave me breath, my father tried to save me only by suffocation – with ever-increasing strictures, with incense-smoke. With fire. Both had wanted better for me, but only one of them would protect me in the end.

I curled into my father’s lap in the passenger seat and studied his face, the way his eyes only looked ahead. His paranoia that I would be invaded by Babylon would dominate my childhood for years to come, but none of us, not even my mother, knew how far he was willing to go to prevent it.

“Don’t worry, Budgie,” he said to me, smiling. “The next place will be better.”