Attendance was “integral to the fulfilment of defence international affairs”, a government spokesperson said.

Support from many African leaders and governments for Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine – or at least reluctance to condemn it – has dismayed western officials.

At the UN general assembly resolution 17 African nations abstained – almost half all abstentions – and one voted against condemning Russia for its ‘aggression’ and demanding a withdrawal from Ukraine, though a majority of African countries gave it their backing. The resolution passed by 141 to 5.

“It harks back to cold war days and the divisions we saw then. But … the objective reality of the international system is so different now this raises a lot of questions about some African countries’ commitment to the post-cold war order and its values,” said Priyal Singh, researcher at Institute for Strategic Studies in Pretoria.

Since the ambassador’s party, the ruling African National Congress party in South Africa has doubled down on its refusal to criticise Russia, saying it hopes to remain neutral and encourage dialogue.

Others on the continent have followed a similar line, calling for peace but blaming Nato’s eastward expansion for the war, complaining of western “double standards” and resisting all calls to criticise Russia.

That the new divide looks like the one which split Africa decades ago is no coincidence. Many countries across the continent are still ruled by parties that were supported by Moscow during their struggles for liberation from colonial or white supremacist rule, analysts say. Though few among their youthful populations experienced the bitter battles of the 1960s, 1970s or 1980s, leaders of ruling parties in South Africa, Zimbabwe, Angola and Mozambique remember how Soviet weapons, cash and advisers helped win freedom.

Mozambique also abstained at the UN, arguing like others that it hoped to encourage dialogue to resolve the violence. So too did Algeria, once seen as a “revolutionary” state close to Moscow.

In recent years Russia has moved to exploit such historic links, underlining ties in public statements, at big conferences and on repeated trips across Africa by foreign minister Sergei Lavrov. Moscow has also pushed its agenda through covert social media networks which portray Moscow as on the side of Africans against western “imperialists”.

“In the Sahel there is a strong anti-western feeling, an anti-imperialist tendency in public opinion and anti-imperialist means anti-US and the west,” said Pauline Bax, deputy director of the Africa Programme at the International Crisis Group.

Mali has recently renewed ties with Moscow after a military takeover there, and the country’s new rulers have called in paramilitary mercenaries linked to the Kremlin to fight Islamic insurgents as French and other western troops withdraw. The Wagner group is run by a businessman who is a close associate of President Putin and is now thought to be present in at least six African countries, including the CAR and Sudan which both abstained at the UN. Boris Johnson announced sanctions against Wagner on Thursday.

Sudan has also tilted closer to Moscow in recent months. The country, where a military coup last year derailed a fragile transition to democratic rule, has concluded a big deal offering Russia a port on Africa’s eastern coast for 25 years. Eritrea – the only nation on the continent to vote against the UN motion– is a brutally repressive authoritarian state which Moscow has also wooed.

Other Russian ties across the continent are strengthened through investment in mining, financial loans and the sale of agricultural equipment or nuclear technology. Rosatom, the Russian state corporation involved with military and civil use of nuclear energy, has sought to expand in Africa in recent years. Russia was the largest arms exporter to sub-Saharan Africa in 2016–20, supplying almost a third of total sub-Saharan arms imports, up from a quarter in 2011–15, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

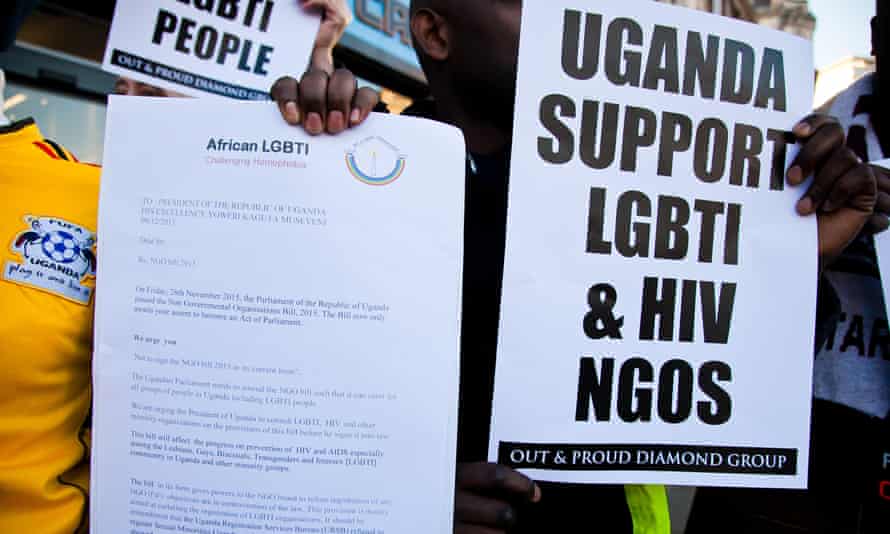

Western officials have been particularly disappointed by Uganda, which has received huge sums of western aid. A once close relationship with the US and the UK has soured over the crushing of political dissent and western pressure to recognise LGBT rights. Yoweri Museveni, in power since 1986, has accused the west of interfering in domestic affairs.

Museveni’s influential son and aspirant successor, Muhoozi Kainerugaba, said on Twitter that “the majority of mankind (that are non-white) support Russia’s stand in Ukraine”.

Uganda’s UN representative said Uganda abstained from the vote on the UN resolution to protect its neutrality as the next chair of the Non-Aligned Movement, a cold war-era group of 120 member states that includes almost every African nation. However Museveni has made little effort to hide his sympathies, criticising the west’s “aggression against Africa” and describing Russia as the “centre of gravity” for the Balkans, like China in south-east Asia.

Nicholas Sengoba, a columnist with Uganda’s Daily Monitor newspaper, said that many authoritarian African leaders like Museveni were pleased to see Putin “stand up to the big boys in the west.”

Analysts say that more recent examples of what is seen as western ‘neo-imperialism” also influences the reaction of many in Africa to the conflict.

“The 2011 Libyan crisis and the Nato intervention there, instability in the Sahel and other experiences mean that many countries buy into the wariness of western dominance and believe that we need a global counterpoint … Russia is seen as representative of the former Soviet Union in this regard,” said Singh.

Reports that some African students have faced discrimination from security officials and others in Ukraine as they attempt to flee the conflict, magnified by social media, have also prompted anger in Nigeria and elsewhere.

But it is unclear how far the positions taken by often elderly leaders reflects broader sentiments, especially among younger populations. The war in Ukraine has laid bare political, social and other divides within countries, as well as among them.

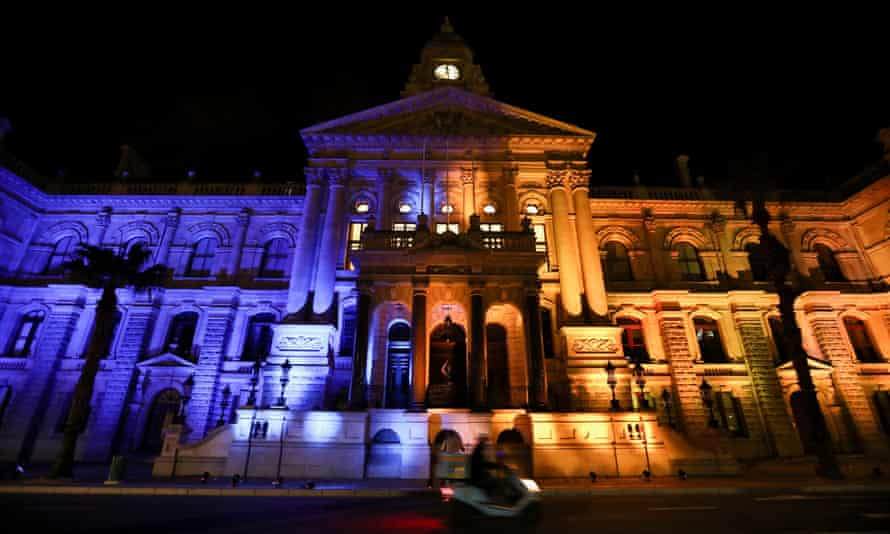

In South Africa, the populist leftwing Economic Freedom Fighters praised Moscow’s action to “avert … a patent and clear security threat to Russian territory and people by Nato forces, and particularly the US”, while the centre right Democratic Alliance projected the colours of the Ukrainian flag on to the provincial parliament in Cape Town, a city it runs, and said it joined “the global condemnation of Russia’s attack on Ukrainian civilians, mostly women and children.”

The anti-western and anti-Nato stance of some on the continent risks overshadowing the early stance against the invasion of Ukraine taken by the African Union, and the speech made by Kenya’s ambassador to the UN, Martin Kimani, who argued that as Africans had suffered imperialist violence themselves for centuries they should not condone efforts to alter or impose frontiers by force.

“It’s important to note that a majority of African nations voted in favour [of the UN resolution] and that regional and continental bodies such as the African Union or the ECOWAS [a West Africa grouping] were quite quick to condemn Moscow,” said Bax.

One recent study found that the 27 African countries that voted for the UN resolution were mostly democracies and all western allies, often actively involved in joint military operations. Most of those that abstained or, like Eritrea, voted against the resolution, were authoritarian or hybrid regimes.