When volunteers at Venue Church in Chattanooga, Tennessee, arrived at their pastor’s house last November, they were hoping to raise his spirits with a surprise visit. Instead they got a shock: Pastor Tavner Smith was alone with a female church employee—she in a towel, he in his boxers.

The charismatic 41-year-old hurriedly explained that the two of them had been making chili and hot dogs and gotten food on their clothes, according to one volunteer who was present. But, as the volunteer put it, “I don’t think none of us was that dumb.”

“If she dropped chili on her clothes, why are you in your boxers?” she recalled thinking. “Was y’all like, throwing chili at each other?”

For the volunteer, the scene confirmed something she had long suspected—that Smith, then married with three children, was secretly carrying on an affair with the employee, who was married to another church staffer. Smith has denied any affair took place, but rumors about it have nonetheless led to something out of a daytime soap opera, involving two divorces, one secretly recorded video, and the departure of nearly all the church’s full-time staff.

And former staffers, members, and volunteers told The Daily Beast they are still struggling to come to terms with the maelstrom that left one of the country’s fastest-growing mega churches in shambles.

“Everyone used to say, ‘Venue is a cult, Venue is a cult,’ and I was like, ‘No, it’s not,’” the volunteer who witnessed the chili incident told The Daily Beast. “And now as I look back I’m like, ‘I don’t think I was in a Godly place.’”

Venue Church’s lead pastor, Tavner Smith

To hear Pastor Smith tell it, he came to Chattanooga by divine intervention. In 2012, as a lowly student pastor at Ron Carpenter’s massive Greenville, South Carolina, megachurch, Smith says he was called by God to move his wife and kids to Tennessee and start a church of his own, in the hollowed-out building of an old Sam’s Club. He claims he was once banned from the mall for recruiting there eight hours a day, and that he recruited hundreds of new members by dropping 50,000 eggs from a helicopter on Easter Sunday. (The egg drop, of course, was God’s idea.) By 2015, Venue was on Outreach Magazine’s list of fastest-growing churches in the country; by 2020, it had campuses in two states and pulled in nearly 2,000 people on a given Sunday.

The services at Venue are standard megachurch fare, where sermons are preceded by rock shows complete with strobe lights and fog machines, and the preaching is heavy on “prosperity gospel”—the idea that donating to the church will increase your own financial fortunes. When Smith takes the stage—usually in a hoodie or a trendy button-down and ripped jeans—he is greeted with a standing ovation. When he makes a joke or preaches something especially meaningful, he is met with a chorus of amens. (At least one volunteer said they were encouraged to respond audibly to Smith’s sermons so the crowd would, too.)

The sermons are heavy on Smith’s personal life, usually consisting of tales of how he overcame insurmountable odds and how you can do it, too, if you accept Jesus Christ as your savior—and donate 10 percent of your income to Venue. In one sermon, Smith insisted that whenever he speaks, “heaven moves” and “angels pay attention.” In another, he claimed God created time zones in order to space out people’s prayers.

“People [in Chattanooga] say, ‘Don’t drink the orange KoolAid,’” one former volunteer said, referring to the vibrant color of Venue’s logo. “They really say that.”

Smith’s sermons also lean heavily on recruitment. Many of them feature stories of him haranguing strangers—a sad young waitress, the real estate agent who sold him the church—into joining the congregation. (They always say yes; they usually cry.) Before Christmas last year, he told his flock to do whatever they could do to pack people into the pews, including leaving baked goods on neighbors’ doorsteps. “If you’ve invited people 72 times and they’ve all but cussed you out and told you to leave them alone,” he instructed, “one more time, invite them to Christmas at Venue Church.”

Once the neighbors got to Venue, there was another message waiting for them: Donate, donate, donate. Attendees said Smith preached over and over about tithing, or the practice of giving a portion of your income to the church every week. Many churches address tithing as a suggestion, but attendees said Smith treated it like an obligation.

“They kept on saying, ‘Bring your friend, bring your friend, bring your friend,’” said the former volunteer, who said she donated up to $300 a week to the church as a high schooler. “And then you get there and it’s like, ‘Oh gosh, he’s preaching on tithing again.’”

The message appears to have worked. Financial records for the church itself are unavailable, but property records show the building alone is worth $4.9 million. A child support worksheet in Smith’s divorce proceedings lists his monthly income as $16,666. According to other divorce records, Smith and his ex-wife owned three houses in and around Chattanooga worth $981,330 combined, and maintained a real estate investment account worth $20,000.

Colt Helton, a church volunteer of more than seven years, said Smith flaunted his growing wealth over the years through designer duds and new cars. After a while, Helton said, he stopped recognizing the church he had joined. “The whole church kinda turned into this kinda shoe and jersey fetish,” he remarked.

But it was the beginning of the pandemic when things really started to change. In early 2020, the usually clean-shaven Smith started growing out his hair and beard, getting new tattoos and piercing his ears. The most noticeable change was how much time he started spending with a certain female employee. Starting that year, one former volunteer said, Smith and the employee seemed “conjoined at the hip.” One volunteer said she saw them having frequent one-on-ones in his office, another she noticed them posting effusive comments on each other’s social media. Rumors began circulating that the two appeared to be having an affair.

The chatter was troubling, but Smith and Venue had accrued a lot of goodwill. Almost everyone who spoke to The Daily Beast credited Venue with turning their life around somehow; by reintroducing them to God or saving their marriage or giving them a community. Volunteers and employees went through strenuous courses and signed strict pledges that bound them together; they were rewarded with seats at the front of the church and beautiful team retreats in the woods. At the beginning, at least, Smith spent quality time with attendees and counseled them through their issues, even giving one couple gift cards so they could take themselves out on date night. “It was super-personable, I felt like people really cared about me,” said one woman who started volunteering with the church in 2016. “Honestly, I kind of did feel like it was God speaking to me at certain points in my life."

Slowly, however, members started noticing a trickle of long-time staff members leaving the church. First was a campus pastor who’d come from South Carolina, one former volunteer recalled. Then—according to multiple former members—a number of full-time staff exited at the end of 2020. Smith and the female employee continued to spend the bulk of their time at church together, while Smith’s wife became increasingly scarce. But whenever anyone confronted the two about the rumors, they denied anything was going on. “It was almost like we were smacked in the face with a pie and then it was just getting all smothered in,” one longtime volunteer said. “Like, lemme make sure I get that pie allll over your face."

In January 2021, Smith announced to the congregation what many staff and volunteers already suspected: He and his wife were splitting for good. He said the board had asked him to take a break from preaching and attend six weeks of counseling. But two weeks later, according to multiple former attendees, he was back at the pulpit, claiming God had told him to return.

As the situation at Venue deteriorated, Smith’s sermons took on an air of desperation. He started calling people out in public for not donating enough and spoke frequently about not associating with “the enemy”—which some took to mean the people who had left the church. The final straw for some was a 16-week series Smith hosted called "Dirty Destinies,” which centered around people in the Bible who had done terrible things but later recovered.

"It was at that point that I started saying, ‘Is this to make him feel better about his decisions?’” one attendee said. “We were kind of like, at that point, how much longer is this going to drag out?"

That former attendee said she had given Smith the benefit of the doubt for months. Both she and her husband had talked to Smith and his alleged paramour, respectively, and both had denied the affair. She figured it was nothing more than a friendship gone a little too far—but still, something in the church felt off. She and her husband were discussing their reservations last month when someone from the church sent them a video. It showed Smith and his employee sitting close together in a restaurant, looking friendly, until she leaned in for what appeared to be a very discreet kiss.

“At that point we were just kind of like, ‘OK that’s the physical evidence,’” the former attendee recalled. “That was the moment that we were like, ‘That’s what we needed.’”

Smith quickly called a meeting with staff and employees to address the video, which was circulating quickly online. The former church member and her husband were in attendance, and said the pastor was evasive and refused to answer questions directly. She said she was stunned by his seeming lack of concern.

“I think that’s the biggest thing: He has no remorse,” she said. “Somebody told me he sees nothing wrong with the decision because he truly believes that’s what God told them to do."

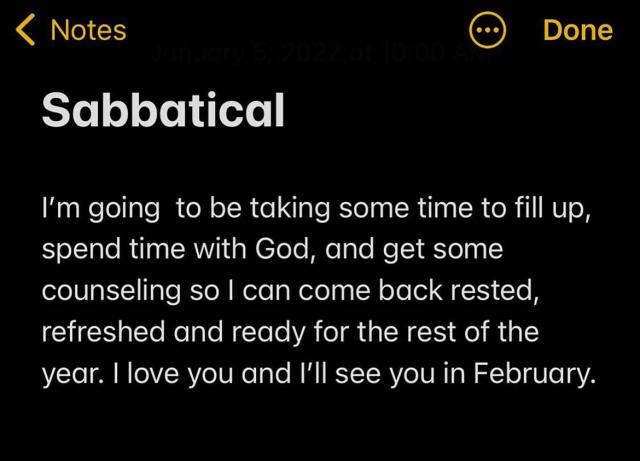

Smith and his wife filed for divorce in May of last year; the split was finalized Dec. 22, the same day the Chattanooga Free Press reported that eight Venue employees had quit. Reports vary on exactly how many staffers remained, but the result was the same: In-person services in Chattanooga were briefly suspended, and the Georgia campus was shuttered entirely. On Instagram, Smith announced that he would be taking a “sabbatical” in order to “fill up, spend time with God, and get some counseling.” He said he would return in February.

Tavner Smith has yet to publicly admit to an affair, but the divorce documents make his ex-wife’s position clear. On her side of the paperwork, she plainly lists the reasons for the split as “adultery.” On a proposed parenting plan, she suggests that the female employee not be permitted around the children at any time, including during church services. (This part did not make it into the finalized parenting plan.) She also requests records of all payments to the woman from Venue Church in 2020 and 2021, as well as records of any of her credit card statements paid off by the church during that time. The employee’s husband filed for divorce this month; his proposed parenting plan suggests none of their children be allowed to attend Venue Church.

Smith’s ex-wife declined to comment for this article, and the most public comment she has made on the divorce is changing her profile picture the day after the divorce was completed. It received more than 900 likes and nearly 300 comments. “Absolutely beautiful heart and soul!” one commenter wrote. “You got this and God will walk you through it all!”

Former staffers and volunteers had been anxious to speak out about the alleged affair, but the emergence of the video opened the floodgates. Former employees, volunteers and attendees took to Facebook to post lengthy missives about their time at Venue, amassing hundreds of comments per post. “I’m so glad this has finally ‘hit the fan,’” one former attendee commented. “I felt betrayed, lied to, and asked to turn the other cheek. I’m just thankful for all the family and friends I met along the way.”

Some of those who left Venue have since found new churches. (The Facebook posts are filled with people inviting the deserters to their own churches, which they promise are truly aligned with God’s word.) Some have even taken up ministry themselves, citing the positive parts of Venue as inspiration. But some former members say their experience at Venue has soured them on church entirely, leaving them questioning what is real and whom they can trust.

Helton, the volunteer of nearly seven years, said he felt Venue has taken advantage of vulnerable people to build the church ranks: low-income workers sucked in by the prosperity gospel, lonely people just looking for somewhere to go. “There were many times people said, ‘We would die for this place,’” he said. “And I was like, ‘Y’all have lost your ever-loving minds.’”

Another former attendee broke down in tears talking about how the church had helped her turn her life around, and how lost she felt without it. Before she joined Venue, she said, she drank, cursed, and was a generally “mean person.” Attending had helped her find her “true self,” she said—or at least she’d thought. Now she didn’t know what to think.

“It was really, really hard, and it’s taken a lot for me to get myself back on track,” she said.