Ken Eto rose through the ranks of the Chicago mob, and then it tried to kill him. The underworld would never be the same.

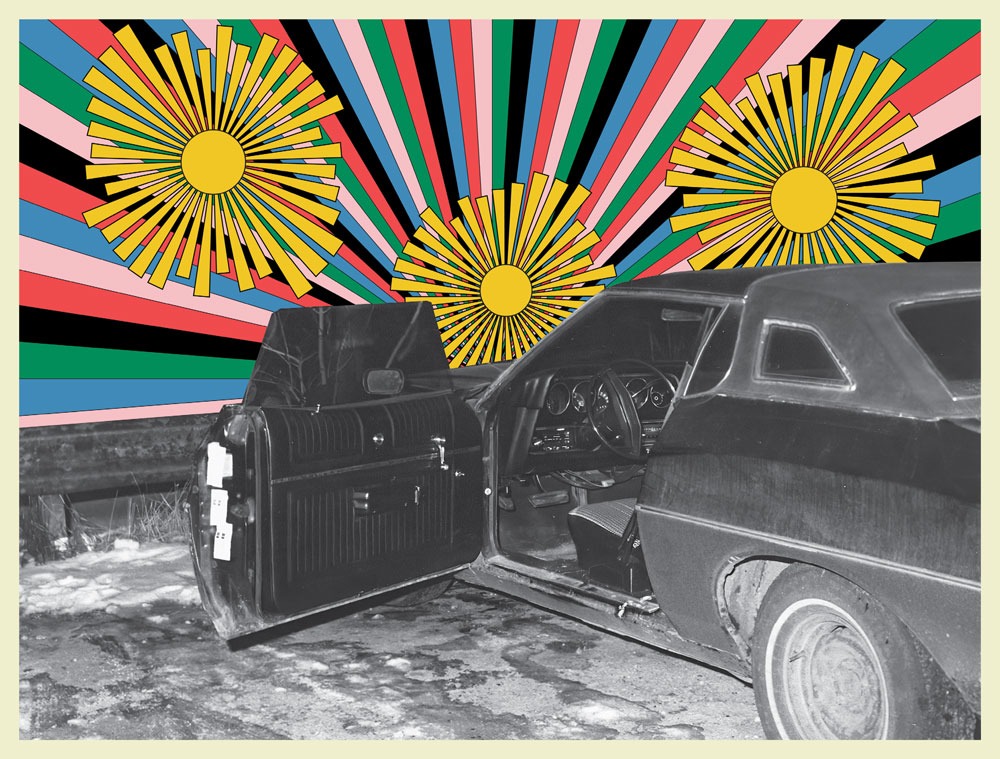

en Eto left the meeting at Caesar DiVarco’s club on Wabash knowing they were going to kill him. It was midday. The plan was to get up with Johnny Gattuso and Jay Campise that evening, then they’d take him to Vince Solano and they’d all have dinner together. Eto walked back to his black ’76 Torino coupe, illegally parked, and saw he’d gotten a ticket.

He drove around for a while. He had to figure out what to do, or what he could do. Around 3 p.m., he got back home to Bolingbrook. The thing was the life insurance. Mary Lou needed to know where the $100,000 policy was. He also had to give her the pawn slips — tell her to get everything out of hock by the end of next week, February 18, 1983, or she’d lose it all. And the lease for the restaurant in Lyons — Mary Lou needed to make sure it got signed. That way, after he was gone, at least some money would be coming in.

He was going out that night, he told his wife — his last dinner with his friends. She asked if he wanted her to go with him.

No, he didn’t. “I hope,” he added, “they’ll be happy.”

Eto took a bath. Drying off, the 63-year-old put on a yellow woven dress shirt, dress slacks, his gray, blue, and white tweed sports coat from Morry’s, and his brown Florsheim buckled loafers. It was already dark out. He had to get to Portage Park by 7:30. He slipped on his tan raincoat and gloves and walked out the door.

Ken Eto sat in his Torino. The temperature had dropped below 30, and the car’s heater wasn’t working. His friends, his good friends, like the ones he’d see tonight, called him Joe. He didn’t know the restaurant they were going to, the one where they’d meet Vince. After nearly half an hour of sitting in the cold, he turned the ignition, reversed into the street, and set off to Chicago.

Driving by the American Legion post where Campise had a regular card game, Eto could see Gattuso already outside, scanning the street. By the time he parked, they were both on the sidewalk, Gattuso and Campise. They took off their right gloves to shake his hand, saying their hellos.

The three of them started walking down the street. Eto asked whose car they were taking.

“Why not yours?” Campise said.

Gattuso squeezed into the back seat of the coupe, settling into the passenger side. Campise rode shotgun, directing Eto where to go. It was a nice little Italian place off Harlem, he said — if he took Narragansett all the way down to where it met Fullerton, then took a right, it was around there.

Eto looked at Gattuso in the back seat. Gattuso didn’t say much.

As they got closer, Campise told Eto to turn at the alley and keep going back — there was a parking lot close to the restaurant, near an old movie theater.

“Go park at the other end,” Campise said, gesturing, “so we don’t have to walk far.”

Eto turned the Torino down the alley. There was only one other car in the lot, an empty old two-door beater. He drove to the end of the lot and slipped the coupe into park. Looking out the windshield, beyond a rusted metal guardrail, he saw a dark stand of bare trees and the rear of the Montclare Theatre.

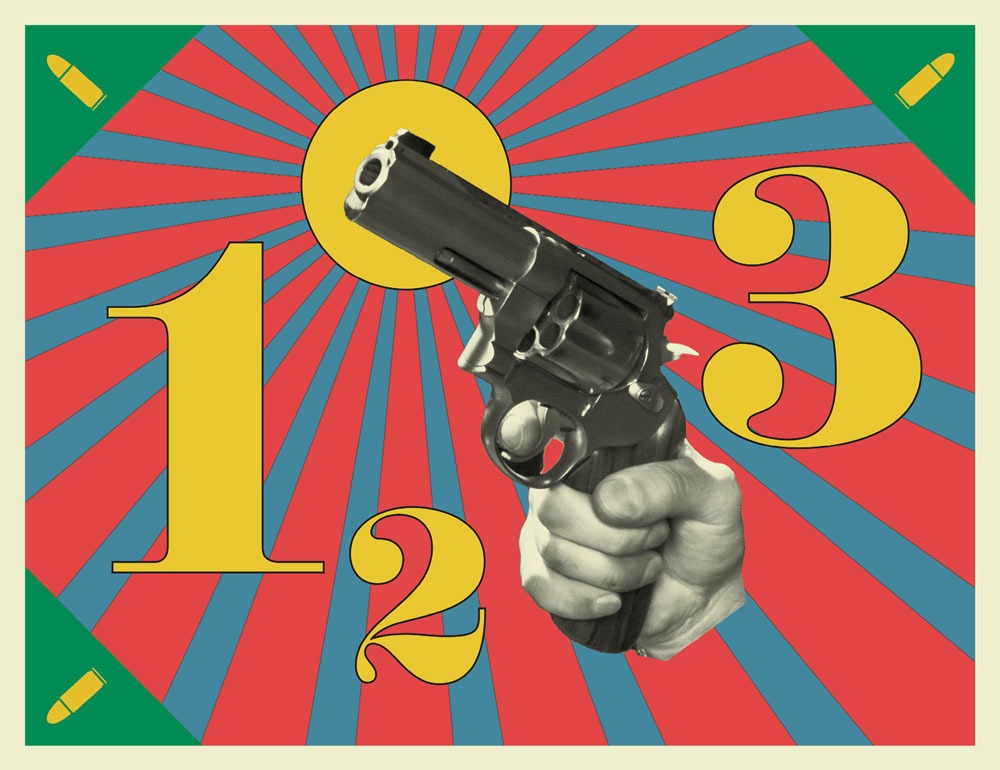

Johnny Gattuso raised the .22 behind Ken Eto’s head and fired. Then he fired again, a ricochet cracking the windshield. Convulsing, Eto slumped over across the front seat. Johnny fired once more into his head.

Campise and Gattuso scrambled out of the car and into the night.

The trouble had all started about two and a half years earlier, in the summer of 1980. It was a Wednesday. Ken Eto had been sitting in room 127 at the Holiday Inn in Melrose Park, tabulating the week’s numbers-betting slips on his Royal portable, when there’d been a knock at the door. He got up and opened it to a pretty brunette he’d never seen before.

“Oh,” she said, flustered. “You’re not my husband.”

Johnny Gattuso raised the .22 behind Ken Eto’s head and fired. Then he fired again, a ricochet cracking the windshield. Convulsing, Eto slumped over across the front seat.

FBI special agent Elaine Corbitt Smith had meant to knock on the door of a room across the hall, the surveillance post from which her fellow federal agents were staking out Eto. After watching him for months through binoculars and telephoto lenses, it was the first time she had been face to face with the man.

Impassive, Eto closed the door.

Agent Smith turned and walked to the right room. The G-men inside snickered as she entered.

Ken Eto’s power to intimidate might not have been apparent in that brief encounter or to any of the thousands of people passing him each day downtown. Per his FBI file, Eto — “Hair: Black, Straight,” “Complexion: Dark, Sallow,” “Occupation: Gambler” — stood 5-foot-5 and weighed less than 150 pounds. He enjoyed dancing, cooking, and watching baseball. He had some knowledge of Spanish. His specialty as a gourmand was chicken Vesuvio, with peas and buttery wine sauce.

Eto had been married three times and was father to six children; his youngest son, Stevie, was his fishing buddy. As Steve Eto tells it, his dad always preferred children to adults, and fishing to the world of adult doings. But there were other ways Ken Eto was very unlike other fathers.

For one, other dads weren’t mentioned in the Chicago newspapers constantly — described invariably as gangsters, racketeers, underworld kingpins. “I used to keep a scrapbook of clippings in a little box of things of my father,” Steve recalls. “I remember at some point thinking, Well, my dad is doing something that’s not quite legal.”

He had seen his dad holding court at a restaurant on Rush Street, receiving envelopes that were jammed with money. “There was one time I asked him, ‘So what do you do for a living?’ ” says Steve. “And he said, ‘It’s none of your fucking business.’ So I didn’t ask him again.”

Growing up half-Japanese in the Chicago suburbs of the ’70s wasn’t easy for Ken Eto’s youngest son. One day, Steve approached his father, seeking advice. Bullies at his predominantly Italian American high school were harassing him. What should he do?

“Next time one of those kids comes up to you,” Steve remembers his father saying, “pull out a weapon.”

Steve wasn’t a violent kid. But he dutifully armed himself; an old-fashioned corkscrew, T-shaped with a wooden handle, would do. And one day at school, one of the usual tormentors walked up to him.

Steve pulled out the corkscrew. “I popped him in the arm with it. And when I pulled it out, it pulled out a chunk of his muscle,” Steve recalls. “He looked at me and he looked at the corkscrew and he ran.”

Later, Steve remembers, the police came to his house. His mother, Judith, called Ken, who talked to the officers on the porch as Steve watched out the window. Suddenly they left. His father came back into the house. There would be no further legal consequences for what had happened. But there was something Steve needed to know.

“If you ever use a weapon on somebody, kill him,” his father said. “ ’Cause if you kill him, I’ll get you off.” Then he added: “If you don’t kill him, you’ll have an enemy for the rest of your life.”

“I knew my dad was somebody,” says Steve. “He wasn’t a run-of-the-mill Joe.”

Elaine Smith would have agreed. For much of 1980, Ken Eto had been her obsession. A Chicago native, Smith had started at the FBI just the previous year, when she was 34, surviving the formidable recruitment and training regimen to become one of about 300 female agents in the bureau at the time. She joined her husband, Tom, her high school sweetheart, as a special agent, and from her first day, the former schoolteacher had been hell-bent on joining the Chicago office’s organized crime unit. After only four months as an agent, she succeeded.

Smith began doing her research on the vast shadow economy of the Chicago underworld. On March 18, 1980, opening a file passed along by a friend, Smith encountered Ken Eto for the first time. FBI No. 276-777-3. Chicago Police Department record 191-799. Known aliases: Joe Montana, Tokyo Joe, and Joe the Jap.

Looking over Eto’s file, marveling at the unlikely prominence of a Japanese American in the Chicago Outfit, Smith saw something profound: “a potential jewel,” in her words, a man she would come to believe to be a sleeper kingpin in the Chicago underworld, and one who had escaped any meaningful consequences for decades.

“He was known to be as high-ranking as one could be in the Chicago Outfit, as high-ranking as a non-Sicilian could be,” says Jeremy Margolis, who served as an assistant U.S. attorney for the Northern District of Illinois from 1973 to 1984. “He was known, he was trusted. He was in the inner circle. And he was the most prolific numbers boss that the Chicago Outfit had.”

The Outfit owned the night in Chicago. There was no force greedier, nor icier in their greed. While their New York brethren favored flashier, public gunfire, the Outfit preferred to deal death quietly — forced disappearances, the fear and dread of the missing’s loved ones confirmed only weeks, months, years later, when an abandoned car in some godforsaken neighborhood finally got popped open. “Trunk music,” as they called it.

This was the underlying threat that had maintained the power of the Outfit. By the time Smith had zeroed in on the Chicago mob, it was an international enterprise. Swollen with money from the bathtub gin and rum-running of the Prohibition era, trailblazing gangster Johnny “the Fox” Torrio had bequeathed his empire to a well-liked former bookkeeper named Alphonse Capone in 1925. In the postwar era, reigning don Tony “Big Tuna” Accardo professionalized the venture, until the Outfit operated much like a massive corporate conglomerate, dominating a mix of legitimate and illegal businesses stretching from Chicago to California and far beyond. According to one mob historian, at the height of Accardo’s rule, the Outfit was earning an estimated $6 billion a year in global revenue.

“The sole goal of organized crime is to enrich the members. That’s all they care about,” says John J. Binder, author of Al Capone’s Beer Wars. And, while not Italian, Ken Eto was one of its biggest moneymakers. Eto’s lofty position in the Chicago underworld was unusual for an outsider, but the syndicate had always been more farsighted than other crime families in promoting gangsters of other ethnicities.

It was less a mark of tolerance than proof of its ambition. Ever since Capone first employed his squad of “American Boys” — a gang of Midwestern killers who looked more like police officers than Mafia hit men — non-Italians had occupied important positions in the Outfit. But all these men had been white. Ken Eto was not. And he wasn’t some despised underling; he was one of the bosses.

Eto was with the North Side crew, a crown jewel of the Outfit’s Chicago holdings, based out of the Rush Street nightlife strip. “He looked after the mob’s gambling interests, particularly,” says legendary reporter John “Bulldog” Drummond, the former resident “mobologist” at CBS-2. Chief among Eto’s illicit enterprises was bolita, a lottery game similar to the longer-established policy racket and hugely popular within Chicago’s growing Latin American community.

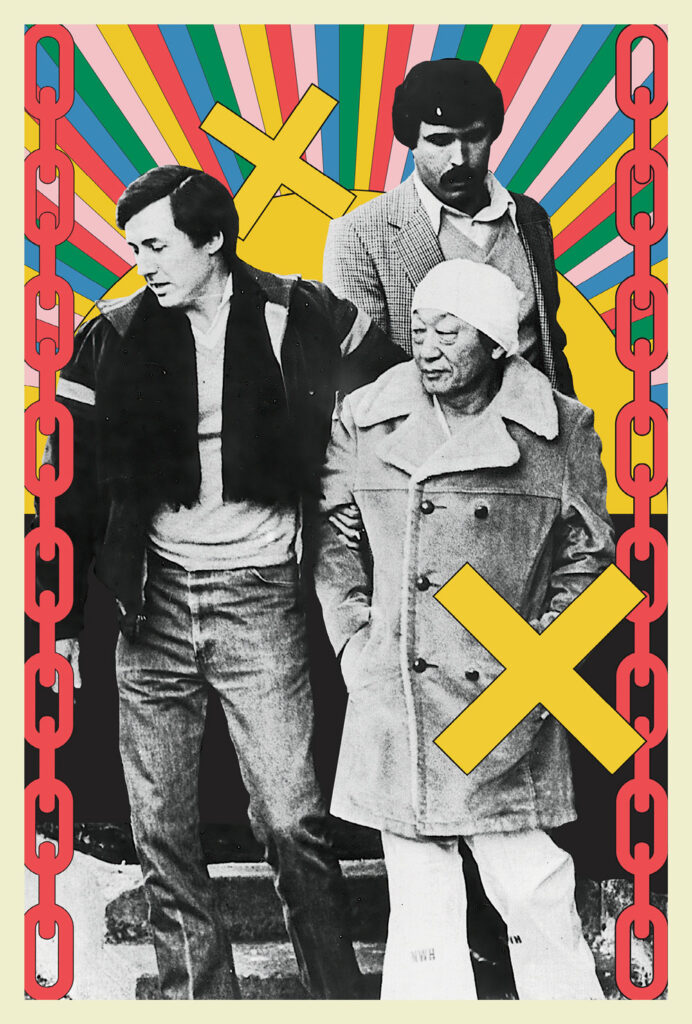

FBI agent Elaine Smith marveled at the unlikely prominence of a Japanese American in the Chicago Outfit, a man she would come to believe to be a sleeper kingpin.

Drummond, known for surprising gangsters on the street with a cigar clenched in his teeth, first met Eto in the early ’70s as the mobster was being bailed out of police custody by one of his many young girlfriends. “He seemed like a mild-mannered guy, although I don’t think he was,” says Drummond. “He was a good provider for the mob. In other words, he produced money, and that’s the name of the game with those guys.”

While the slight, raspy-voiced Joseph “Caesar” DiVarco served as Eto’s immediate manager on Rush Street, the greater North Side was skippered by Vince Solano. Officially, Solano was president of the Laborers’ International Union of North America Local 1. But unofficially, he was in charge of all Outfit business north of the river, between the lake and the North Branch. A cautious, experienced, and somewhat stiff labor racketeer, he rarely socialized with his soldiers. He had stopped holding the annual North Side Christmas parties, at which he handed out envelopes of cash, for fear of FBI surveillance.

From his perch on Solano’s North Side, running Rush Street nightclubs like Faces and Bourbon Street, Ken Eto served as the Chicago Outfit’s most adept minority relations specialist — a gambling czar of the highest caliber, able to extract millions of dollars over the years from Chicago’s Puerto Rican, Black, and Chinese American communities. In just the couple of months leading up to Smith knocking on Eto’s door, the total sum of betting in the bolita racket exceeded $3 million.

Such moneymaking acumen in his roughly three decades working for the Outfit had earned Eto his reputation. About once a month or so, he would call up Solano at the union hall, saying it was “the pizza man,” and they’d meet at a nearby IHOP on the Northwest Side for Eto to update him on gambling operations.

But Eto wasn’t just some harmless guy running a profitable enterprise. “He was generally viewed,” says Margolis, the former prosecutor, “to either have had blood on his hands directly or certainly indirectly. He was viewed as a very bad and dangerous man.”

In 1958, the police had questioned him about a gruesome homicide. Santiago “Chavo” Gonzalez was still well dressed when found in a vacant lot, befitting his monied stature in the Puerto Rican community as a bolita operator. He had been disemboweled. Gonzalez’s frantic widow said it must have been about gambling — he’d been badly beaten with a tire iron by some men the year before on Clark Street, and though she had not seen him among the men who’d dragged Chavo out of their home, she was unequivocal that “a Chinese man named Joe” was their boss.

Delving deeper into Eto’s file, Elaine Smith would soon find there were more homicides attributed to his takeover of the bolita and policy rackets in the 1950s and ’60s, all unsolved. Men dragged from their homes, dumped in vacant lots, their throats slit and bellies slashed. But even more troubling was Smith’s suspicion that Eto must have enjoyed the protection of corrupt Chicago police officials.

A few days after the hotel door mishap, there was another knock at room 127. Eto had arrived about 10 minutes earlier and was just settling into the count. Walter Micus, his slovenly flunky, got up to open the door. Standing there was a federal agent heaving a battering ram backward, caught in midswing.

Micus took one look at the swarm of feds, fell to his knees, and vomited all over himself. FBI agents flooded the room. Eto was cuffed face-down on the floor. He remained stonefaced as agents helped him back up to his feet and began searching the room.

This time, they had a warrant. And there all the slips were, on the table, in front of the Prince of Bolita himself, vassal of the Outfit, the crime syndicate powerful enough to forge history and break cities. Ken Eto, still handcuffed and betraying no emotion, asked if a federal agent could take his glasses out of his front pocket, please, and put them on his face.

In the leather-bound journal he kept in 1919, now falling apart with age, Mamoru Eto recorded an entry on October 19, at 7:45 p.m., in kanji so old-fashioned it is difficult to read today: “My wife safely delivers. I am truly grateful. … And he is a boy. My joy knows no bounds.”

While Mamoru had been born in a little town on Kyushu, the southwesternmost of Japan’s main islands, his firstborn son, Ken, had entered the world on the outskirts of Stockton, California, at the edge of the San Joaquin Valley. The Golden State may have been the winner’s circle to those who’d stormed west, but for the Japanese who’d crossed an ocean to get there, America’s back garden was only the beginning of their journey.

In old photos of him as a young man, with his shaved head and black eyes, Mamoru Eto blazes with presence. A decorated combat veteran of the Russo-Japanese War, Mamoru claimed descendance from samurai, the caste of warriors who’d been stripped of their swords and powers a decade before his birth. He was already 34 when he’d left for the United States, planning to stay only long enough to study in Massachusetts. When he arrived in San Francisco, he saw migrant workers who had come to America hoping to someday return to their homelands, only to gamble away their earnings each night.

He’d intended to complete his studies and return to Japan’s Kwansei Gakuin University as a professor armed with an American education. He would coach rugby and teach kendo, the Japanese art of swordsmanship. But Mamoru never made it to Massachusetts; instead, he sent for his wife, Kura, and 2-year-old daughter, Hitoko, to join him in California. Two years later, Ken was born, and the family moved an hour southeast to Livingston, where, acre by acre, from tenancy to small holding, Japanese farmers were gaining a foothold in California agriculture.

Something had altered Mamoru Eto in California. He had seen it one day in the sky over the fields where he worked as a laborer: a religious vision, an image of God. The severe Christianity he zealously adopted would dominate the rest of his life, and the lives of his young family.

Most of the year, Mamoru would work on the farm, but in the winter, he would leave his family to travel across California, preaching in Japanese to other migrant workers across the state. Kura was left behind to care for the children, surrounded by towns where billboards with messages like “No More Japanese Wanted Here” loomed over the roads.

When Ken was in the fourth grade, the entire family moved to Pasadena, where Mamoru had secured a job tending gardens. As Ken’s sister Helen recalled years later, her father established the First Japanese Nazarene Church in their living room, preaching incessantly at home. Under the unrelenting strain of Mamoru’s Christian fundamentalism, his wife suffered the most. Kura seemed invariably confined to her bed, prone to deep, dark bouts of depression.

The Eto patriarch was an abusive martinet who meted out strict punishment. In one instance, he seriously burned Ken’s younger brother by holding his wrist to a heating pad. The oldest son, Ken increasingly chafed at his father’s brutal treatment. His younger brothers looked up to him as a “tough buddhahead,” who stood up to not only their father but also the white children who bullied him for being Japanese.

Even as a young teenager, Ken Eto was not going to put up with anything he didn’t want. Around the lowest point of the Great Depression, with a quarter of America’s workforce unemployed, he ran away from home, drifting across California and up to the Pacific Northwest. He would never return to live with his family again.

More than two years after his arrest by the FBI, Ken Eto had accepted that he was going to prison on the bolita charges. He had taken a stipulated bench trial, putting up no defense but not pleading guilty. Summarily convicted on January 18, 1983, he’d take whatever term the judge gave him in the sentencing hearing coming up February 25. It wouldn’t be much.

As Eto got his financial affairs in order, he got a call at home: It was Joseph “Big Joe” Arnold, DiVarco’s right-hand man. DiVarco wanted to meet. When Eto got to the car dealership on the West Side the next morning, DiVarco explained that the skipper, Vince Solano, was concerned. He hadn’t heard from Eto recently, amid all this business on the federal charges.

Eto said there’d been nothing to report. He didn’t have any games going, no rackets, no bolita. No sportsbook, even with the Super Bowl a week or so away. He knew he was going to prison and was resigned to it. Nonetheless, DiVarco said, Solano wanted to see him.

The next morning, Eto went to a pay phone and dialed Local 1. It’s the pizza man. Solano told him to meet at the usual spot around lunchtime.

When Eto arrived at IHOP, he saw that the boss was already there, alone outside. Eto joined him, and Solano started walking away from the restaurant. He was hunched over, his face cast down at the sidewalk. “I thought I told you to take a trial,” he said.

Eto didn’t recall Solano saying that. He had figured he’d get less time and still preserve appeals possibilities the way he’d done it. It would only annoy judges and prosecutors to draw out a slam-dunk case, while the Outfit’s overlords would never take kindly to a guilty plea.

Well, Solano said, Eto had three choices. One: Appeal. Two: Do his time. Three: Run away.

The two gambling charges carried a max of five years each, and Eto knew he wasn’t going to get that much. He certainly wasn’t going to run away.

“Appeal it,” Solano told him.

OK, he’d appeal it. Vince turned back toward the IHOP. Eto turned alongside him.

“What are you looking back for?” Vince asked, jumpy.

“I thought we were going back,” said Eto.

“No.”

They kept walking. It was hovering around freezing.

Then Solano asked Eto a question: He still had that restaurant and nightclub in Lyons, right? Yeah, Mary Lou’s, named for his wife. It was vacant now, sitting unused. He had an offer on it, a good offer, from a guy in La Grange.

Well, Solano said, Johnny Gattuso had a backer, and Jay Campise wanted to come in as his partner, so Joe should see about meeting with them.

It was an unexpected request, far below Solano’s pay grade. And on behalf of Gattuso, of all people, who wasn’t even made. Nonetheless, Eto agreed to take the meeting: Orders were orders. He would set something up.

The two men made their way back to the parking lot and Eto’s car. Suddenly Solano asked Eto what was in his pocket.

Eto had his hands in his pockets and took one out, holding a pack of cigarettes. The boss eased a bit.

“I thought I saw something,” he said.

In the weeks after the March 24, 1942, order from the U.S. Army’s Western Defense Command that “all persons of Japanese ancestry” on the West Coast would be subject to an 8 p.m. curfew — in response to Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor — one 22-year-old drifter would be caught in violation and arrested near Tacoma, Washington. This was the inaugural entry on the rap sheet of a young Ken Eto.

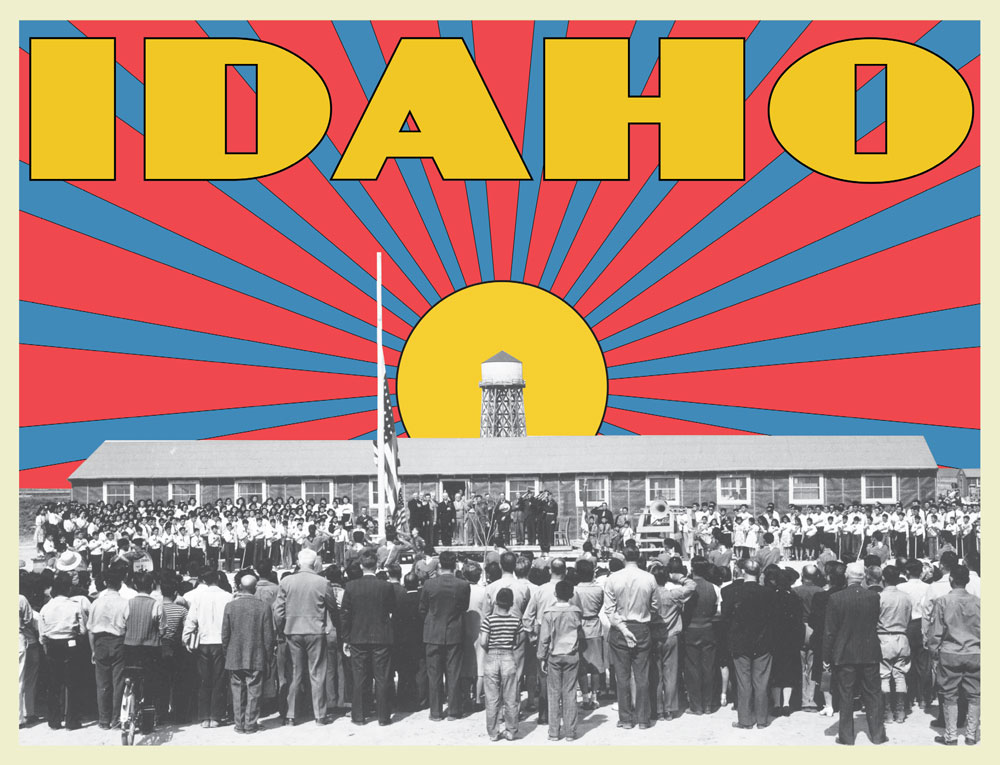

The curfew was a mere prelude to what was to come. Soon the Western Defense Command would launch a massive civil operation on the Pacific Coast: the forcible detention of ultimately more than 120,000 Japanese American men, women, and children in desolate concentration camps in the American interior. Eto was sent to the Minidoka War Relocation Center, hastily constructed on the Snake River Plain in the high desert of southern Idaho. His family was held at a camp in Arizona.

Plagued by frequent dust storms, prone to days that hit triple-digit temperatures and nights that fell below freezing, Minidoka, with its armed guards and barbed-wire fences, was a forbidding place. Living in drafty shacks with gaps in the floorboards and little more than tarpaper roofs to keep out the cold, Eto, along with more than 13,000 other Japanese Americans, would spend time there during World War II.

Up until then, Eto had supported himself with seasonal jobs, picking fruit and working in canneries. To survive as a teenage runaway, he’d learned to suss out danger quickly, clocking people who couldn’t be trusted, exploiting any opportunities for making money — and observing his fellow migrant workers at the labor camps, particularly while they gambled.

“I understand that you have a job to do,” Eto told Smith, “and trying to convince me to be a snitch is part of it. But that is not who I am.”

In a similar way, internment would not be a total waste for Ken Eto. As recounted in the pages of the Minidoka Irrigator, the inmate-run newspaper, gambling rings were organized throughout the camp system to provide a distraction from the tedium, and Eto took part in them. “He was a great gambler,” says former assistant U.S. attorney Margolis. “Just a super card player who understood the numbers.” Later, Eto would describe Minidoka as his finishing school, a place that gave him ample opportunity to perfect his skills.

Not that he didn’t harbor other feelings about his time in the camp. “We talked about what being a Japanese American meant to him,” recalls Margolis, “what it meant to him to be treated the way he was treated. I think that had a real impact on him. He might’ve done something else with his life had he not felt that kind of bitterness and resentment, and rightly so.”

Anight or two after he’d met Vince Solano at the IHOP, Ken Eto got another call from Big Joe Arnold. Johnny Gattuso and Jay Campise were going to be near Eto’s restaurant in Lyons the next morning. They’d like to talk to him over coffee about leasing it. At the meeting, the two said they wanted to turn it into a pizzeria. Eto explained that he’d already found someone to lease it, and that another pizzeria in Lyons hadn’t done well.

Well, Gattuso said, the way he saw it, he was doing Eto a favor, taking the place off his hands. He promised he’d bring his financial backer the following day at 10 a.m. for a final decision.

That morning, Eto had to drop off his Torino with a mechanic to have the radiator fixed. So Mary Lou followed her husband to the auto shop, then gave him a ride to the restaurant bearing her name. They sat waiting in the parking lot. The weather was terrible, and Johnny Gattuso was late.

Around half past, Gattuso finally rolled up in an orange Chevy Camaro, a beater. He was alone. Eto got out of the car and ushered him into the vestibule of Mary Lou’s. Gattuso said he couldn’t get in touch with his backer — it was a long story.

Well, the guy from La Grange was ready to sign for the place, Eto told him, so Gattuso should write down the guy’s phone number and call him as soon as he’d had a chance to talk to his backer. Gattuso took out a pen and opened his wallet for a scrap of paper, revealing a Cook County sheriff’s badge tucked inside.

Oh, don’t worry about that, said Gattuso. He wasn’t a cop. Well, he was a sheriff’s deputy, technically, but it was as a part-time employee, a process server who’d supposedly deliver warrants a few days a month. This kind of thing had long been done for connected guys. Besides, it wasn’t the worst idea, in their line of work, to have a badge.

Meanwhile, Mary Lou waited outside in the parking lot. She wasn’t alone. Across the street, she noticed two men sitting in a brown car parked on Ogden, facing the club. They seemed to be in their 40s, each wearing some type of hat.

About 15 minutes later, she watched the man she’d later learn was Johnny Gattuso exit the club and drive off. The thing she’d remember, some weeks later, was that at just the same time, the two men in the brown car drove off, too.

Months later, as a Chicago Tribune story would report, the FBI figured out what happened: The Outfit had lured Eto to be shot in the vacant restaurant. But there had been an unexpected wrinkle: Mary Lou, playing chauffeur that morning, had likely spooked the hit men.

A leaky radiator had granted Ken Eto a stay on his death sentence. For a little while, at least.

It was two days before Christmas 1950. Prisoner No. 8092 had been in the Idaho State Penitentiary since October, when he’d been sentenced to 14 years. Along with two coconspirators, Ken Eto had used a variation on the classic “pigeon drop” scam to swindle a local out of $5,000. He persuaded the mark to front some money for a shipment of jewels he had coming in, in return for a bigger payout later. In reality, of course, there were no jewels.

Now, after interviewing the convict, an institutional parole officer at the prison submitted his admission summary. There was much to like about his subject. Eto, 31, was “of high normal intelligence,” with an IQ of 109, and “very friendly, outgoing … at turns frank and revealing and at other times somewhat evasive and noncommittal.”

Since his release from Minidoka (according to one story Steve Eto heard, his father got out “by saying he was Chinese”), Ken Eto had spent most of his 20s traveling across the country solo, just as he had along the West Coast earlier. But this time, instead of supporting himself as a migrant laborer, he had worked as a dealer, cardsharp, and pool shark. For two years, he dealt cards off and on at a club in Denver, building his own bankroll on the side. He’d spent so much time gambling across the High Plains states that he earned the nickname Joe Montana.

Eto moved back to Idaho in 1949. By his own admission, he’d developed a “greed for easy money” as a grifter, and soon he was fleeing the state for Chicago. It was there that he married his first wife, Teresa, one of the city’s many Polish Americans, and became a father. Teresa would give birth to five of Eto’s six children.

It was also in Chicago, on Valentine’s Day 1950, that Ken Eto was arrested on the Idaho charges. In the nine months he spent locked up, he was a model inmate. He worked as a janitor in the prison hospital and became an avid student, taking courses in English, citizenship, restaurant management, and bookkeeping.

What had happened in Idaho wouldn’t happen again, Eto assured the parole officer. He’d learned his lesson. “Prognosis,” the officer concluded, “is considered favorable. Further delinquency involvement does not appear to be indicated.”

Eto returned to Chicago, where his wife would play a role in her new husband’s future career. Teresa Eto was a gambler herself and ran a card game that drew Outfit affiliates. “She’s the one who introduced him to people that were connected in organized crime,” says Steve Eto, who would come to know her as Aunt Terry.

Years later, an informant would furnish an additional insight into Ken Eto’s underworld education: Delinquent on a juice loan he’d taken from an Outfit loan shark, the young gambler had been beaten by mob enforcers. But Eto, according to an FBI report, “displayed such stoicism that he impressed the hoodlums and was eventually employed by them.”

The last time Elaine Smith saw Ken Eto before he was shot in the head was at the Chicago FBI office on September 16, 1980 — a few months after the Holiday Inn bust. After taking his fingerprints, obtaining a mug shot, and administering a handwriting test to see if his penmanship matched that on the bolita slips, Smith sat down with two coffees.

“You know, Mr. Eto, we would very much like you to cooperate with us. We need the help of people like you to defeat the Outfit,” Smith told him, as she recalled in the memoir she wrote years later.

What Eto did next surprised her: He took her hands in his. “I understand, Agent Smith, that you have a job to do, and trying to convince me to be a snitch is part of it. But that is not who I am.”

He continued: “I know I may go to prison for some time. But I could do that standing on my head.”

This was the first time the taciturn racketeer, old enough to be her father, had ever really spoken to her. Elaine Smith knew little of his past then — his childhood, Minidoka.

“I will never cooperate,” Eto added. He withdrew his hands from hers. “This is nothing to me.”

Afew days after Ken Eto met Johnny Gattuso at the restaurant, Big Joe Arnold called again. Caesar DiVarco wanted to meet with him at his social club, Oldsters for Youngsters, at 11:30 a.m. the next day.

Eto arrived and greeted DiVarco and Arnold, along with a Greek bartender named Pete. Arnold had to run some errands, so he put his coat on and left.

DiVarco sat down with Eto to talk about this lease. Eto explained that he had never heard back from Johnny Gattuso, so he’d made the deal with the La Grange guy.

Well, Caesar said, tonight Eto needed to meet Gattuso and Jay Campise at the American Legion. And then they’d all go have dinner with Vince Solano, the North Side skipper.

In the decades since he had first met Solano in the ’50s, in all the years he’d dutifully sent millions of dollars in gambling proceeds up the chain, Eto had never been invited to dinner with the boss.

Walking back to his car, now decorated with a parking ticket he’d never pay, Eto knew that after all this time, after all the work he’d done for them, the Outfit, his associates, the men he thought respected him, the men he’d enriched for years — they didn’t know him at all. He would never snitch.

They were going to kill him for nothing.

Inside the Torino, Ken Eto’s body was slumped across the front seat, blood still dripping out the six entrance and exit wounds. A few minutes had gone by. Eto opened his eyes and sat upright.

When the first shot had hit the back of his head, he’d thought: I knew it. So this is it, just like I’d figured. But then, as the second bullet hit, he’d realized: I ain’t dyin’. By the third shot, he’d started shaking, falling to his side, convulsing, pantomiming his own death throes. He heard the sound of Campise’s and Gattuso’s footsteps growing fainter as the men ran from the car.

He’d been shot three times in the head and hadn’t even lost consciousness. His blood had soaked his shirt, and pooled on the front seat, and dripped all the way down into his loafers. He was in a lot of pain, tremendous pain, and he couldn’t hear too well, either — but he was alive.

Looking out the windows, Eto couldn’t see anybody else around. He got the driver’s side door open and lurched out. As he staggered across the icy parking lot, blood drops spattered from his head onto the asphalt. He slipped and fell to the ground, struggled to his feet again. That beater car Eto had seen when he drove into the lot was gone.

When the first shot had hit the back of his head, he’d thought: I knew it. So this is it, just like i’d figured. But then, as the second bullet hit, he’d realized: I ain’t dyin’.

Eto stumbled back toward the street, blood trailing him in the snow. Reaching Grand Avenue, he saw the lights of a bar up ahead. That didn’t seem like the best idea. He kept walking. An old-fashioned neon marquee sign on the façade of the Terminal Pharmacy was lit: “Free Delivery.”

Eto walked in sometime after 8 p.m. Morris Robinson, the pharmacy’s owner, was on duty. “I just asked him what was wrong,” he would tell John Drummond the next day for a TV news report. “And he didn’t say anything. I said, ‘What happened to you?’ He said he was shot. I said there weren’t any doctors here. He asked me to call him an ambulance. I called him an ambulance.”

The paramedics arrived minutes later. Along with a police cruiser.

In addition to the six holes in his head and a screaming headache, Eto had gained some other new problems in the past half hour — chief among them a healthy fear of the Chicago police. It was the first time he’d been afraid of the cops in years. But now the days of ingratiating himself with his old friend, Detective Fred Pascente, with dinner for him and his pals on the Organized Crime Task Force were over, just like that.

The corrupt Chicago police force wasn’t going to protect him anymore, and he knew it. It might even try to finish the job of killing him. So as the paramedics tended to his wounds and loaded him into the ambulance, Eto, dazed though he was, insisted the younger of the two cops on the scene, a rookie, get in the back with him for the ride to the hospital.

Elaine Smith was out of town in Colorado when the phone rang in her hotel room. It was Bill Brown, her supervisor at the FBI. Ken Eto had been shot. Not only that, he had survived and was asking for her.

Smith was astonished. Why would they shoot him? It made no sense. Facing a year or two at most on the gambling charges, Eto had remained stone silent in the face of all efforts by the FBI to turn him. She knew this personally.

Who might have been the triggerman? Brown asked.

Smith was gobsmacked. Obviously, this had come down from the bosses on the North Side — a hit like this would need to be sanctioned, possibly even by the upper echelons in the suburbs. After a few moments, Smith threw out a couple of names, including a veteran North Side soldier.

“Jasper Campise?”

By 9 p.m., a phalanx of federal and city authorities had descended on Eto’s hospital room, sealing him off in tight protective custody. It was unfamiliar terrain for all involved. In the history of Chicago crime, plenty of gangsters had been felled by a hail of bullets. But few had survived — certainly never a mob boss as prominent as Eto.

By 11:30, Eto had been stabilized. Trauma doctors at Northwest Community Hospital quickly concluded that not only had he suffered no brain damage, but none of the bullets had even cracked his skull. The .22 had always had a reputation for reliability with Outfit hit men, but here it had failed them. Perhaps the assailants had used old ammo or tampered with the gunpowder to reduce the noise.

Whatever happened, three point-blank shots to the head had miraculously left Eto with little more than superficial wounds, his braincase intact. He had a nasty concussion. But he was conscious and able to talk.

With Elaine Smith in Colorado, any initial breakthrough in getting information from him would have to be made by someone else. But Eto had enough of his wits about him to refuse to talk unless he could be assured it would not lead to charges against him. And he knew what talking meant: Not only would he be turning informant, but he would also be turning the page on his decades of syndicate service. Once he mentioned a single name, there would be no going back.

The FBI needed a federal prosecutor who could offer Eto immunity. So they called on assistant U.S. attorney Jeremy Margolis.

This happened to be the monthly Thursday night that Margolis’s terrorism task force in Chicago got together for what they called “choir practice.” Explains the prosecutor, a native Chicagoan who was 35 at the time: “From 7:30 until about 12:30, we would sing and dance and have a cocktail or two at the BeefSteak Inn on Sheridan Road and Morse Avenue.” As he was leaving that night, his pager pinged. He was to call the FBI right away. After Margolis found a pay phone and dialed in, the bureau patched him through to the FBI’s top man on the scene at the hospital, Ed Hegarty.

“Tokyo Joe has just been shot. Can you get down here immediately?”

Speeding in his U.S. Marshals Service squad car, Margolis made it in less than 12 minutes. He arrived to find Hegarty, Bill Brown, and, he recalls, “many, many, many other agents and Chicago police officers” in the hospital corridor.

The federal agents brought Margolis up to speed. Eto would likely ask for immunity. He would likely ask about the witness protection program. And he needed to be flipped — now.

Journalists were beginning to gather that there was something drawing the police to the hospital. Once word filtered back to the Outfit that Eto had survived, if it had not already, its first move would be to kill the hit men who’d messed up. “Once they got whacked,” says Margolis, “you have no witnesses to identify Vince Solano, who was the boss that we all assumed was the guy who ordered the hit.”

Alongside Hegarty, Brown, and Chicago police investigator Phil Cline (who would later become superintendent), Margolis entered the hospital room. Eto was sitting in bed, hooked up to an IV drip, his head now heavily bandaged. Blood shimmered through the gauze. Someone turned on a tape recorder. They began talking.

“There is no more bond,” Margolis told Eto. “It’s not you that’s breaking it. They broke it. They broke it by trying to kill you.”

Eto knew that of the men around his hospital bed, only the young prosecutor had the power to immunize him. He requested that everyone leave the room except Margolis. They did. The tape recorder was turned off. It was just the two of them and the sounds of monitors beeping and whirring.

“I understand what you’re thinking, and I understand the difficulty that you’re facing,” Margolis told Eto. “I know what face and respect means to you.”

Eto was a man of his word. Margolis knew this. He also knew betrayal would not come easily to Eto, who had been told by his father that he was descended from samurai — warriors of virtue, chamberlains of the feudal lords, expected to fall on their swords rather than betray their masters. The federal prosecutor shared some ground with him on this: Like Mamoru Eto, Margolis’s father was a swordsman, belted in aikido, karate, and kendo. Margolis told Eto of his own journey to become a seasoned judoka, of the Ginza festivals he’d attended at a local Buddhist temple, of the code of courage and loyalty to which Margolis knew Eto adhered: both the warrior’s code of Bushido and the gangster’s code of omertà.

Eto wasn’t a sentimental man. Margolis saw him as a cold, calculating figure; his business required nothing less. But as Margolis became less of a stranger to Eto, the prosecutor sensed the walls between them beginning to fall.

Margolis leaned in. He began to make the bigger point: Eto was no longer obligated to the Outfit. “There is no more bond,” he said. “It’s not you that’s breaking it. They broke it. They broke it by trying to kill you — because they didn’t understand that you would’ve gone to your dying day without breathing a word about them. You know that, I know that. They didn’t trust you.” He paused, letting the words sink in.

“You know why?” Margolis continued. “Because you’re Japanese.”

With the concussed Eto having trouble hearing, Margolis leaned in closer. “They didn’t trust you because you’re not like them, and they tried to kill you because you’re not like them. And it’s not that you now owe them less. You now owe them nothing. The vow is gone. They tried to kill you unnecessarily, improperly, wrongfully.”

The injured mobster eyed him warily. Margolis moved on to the cold truth of Eto’s situation. “You and I both know that you have no choice. The issue isn’t what must you do. The issue is how quickly you do it.”

Margolis estimated they had somewhere under an hour left to find and arrest Eto’s assailants before word leaked out that their target had survived. By not talking now to the feds, Eto wouldn’t just be putting his life in further danger, Margolis reasoned with him; he’d be losing something precious: the chance for revenge. “You give us their names,” vowed Margolis, “and we will go out and get them and then try to get Vince Solano for what he tried to do to you.”

Eto thought about it. To run headlong in the opposite direction from the one his entire life had taken, with only a few minutes of consideration — this was the demand. Violence had always trailed Eto, had robbed him of his childhood, of his freedom. It had defined him. And then he had mastered it. He had found his place within it. He had become a man to be respected and feared. But now the violence that had ordered his life had turned against him again.

Ken Eto looked at Jeremy Margolis.

“OK.”

Having gotten the answer he wanted, Margolis exited into the hall, where the assembled agents and cops burst into applause. They had overheard everything. Margolis hadn’t realized he’d been shouting at the deafened Eto. But they still had to make things official. So Margolis and the other high-ranking officials walked back into the room, a tape recorder now running.

Margolis put his badge and federal credentials into Eto’s hands, then clasped his own hands over Eto’s, which were smeared with the blood that had seeped through the bandages. Perhaps for the first time in his life, Ken Eto began thinking aloud for an audience.

“They took my freedom away,” he rasped. “I can’t walk the street. I have to fight them. They had their shot. They muffed it. I think I would be better off if they didn’t muff it. But as long as they muffed it, maybe I shall go this route.”

And with that, they then cemented the deal: immunity in exchange for cooperation.

Elaine Smith was woken again by a second phone call. This time, it was from Bob Walsh, another supervisor at the FBI: Eto had flipped. He’d named the gunman: Johnny Gattuso. Jay Campise had been there, too, to set Eto up.

The Chicago police had arrested Gattuso at his home in Glenview before dawn, then Campise at his condominium in River Forest. When she was back from Colorado, Walsh continued, they would need her help to turn Eto into their star witness and bring the Outfit down.

Smith was breathless. Eto had been her case. She would be on the next plane, whatever it took. Walsh stopped her.

She should have her vacation, and get some rest and relaxation. When she got back, Eto would be all hers.

Jay Campise and Johnny Gattuso had been plunged into an inferno. The men who had conspired to murder Ken Eto had now traded positions with him. While Eto recuperated under tight federal protection, Campise and Gattuso were confined to the hell of the Metropolitan Correctional Center, the grim, wedge-shaped federal jail in the Loop.

Neither Campise nor Gattuso had so far talked to the FBI, but the authorities felt sure the Outfit would try to kill both regardless. The challenge facing Margolis and the other principals of Operation Sun-Up, the federal operation launched off Eto’s cooperation, was to keep them alive long enough to be persuaded to talk.

After the two made bail on state charges of attempted murder, Margolis, fearing their immediate elimination once out on the street, indicted Gattuso and Campise on federal charges of violating Eto’s civil rights. “I argued for very, very high bonds, arguing that they were huge flight risks,” recalls Margolis. “And the argument was, ‘They have no choice but to run.’ ” The gambit worked. With bail set at $1.8 million for Campise and $1.5 million for Gattuso, authorities figured neither would be leaving lockup anytime soon.

Margolis had to convince only one of them that their survival depended on talking. But turning them would not be easy. Jasper “Jay” Campise, 67, was an experienced Outfit soldier. A potbellied, toad-faced juice loan man rarely seen without a cigar hanging from his mouth, he had narrowly avoided a murder charge in 1966 and had little patience for federal prosecutors.

“Fuck off, kid,” Margolis recalls Campise barking as he came calling at the MCC.

Sitting across from the aging crook, Margolis realized that Campise truly believed his Outfit status would get him a pass for the Eto fiasco. Even in jail, he felt untouchable. “I told him, ‘You’re dead,’ ” says Margolis. “And I could tell in his face that he didn’t believe it.”

While the overweening Campise had been defiant, Margolis encountered an entirely different demeanor when confronting the man who’d actually shot Eto. Gattuso, petrified and exhausted, “looked defeated,” recalls Margolis.

John Gattuso, 47, was a mere mob associate — a hanger-on, relegated in the past to managing syndicate restaurants, strip clubs, gay bars, and bathhouses. Perhaps shooting Eto had been his opportunity to become a made man with the Outfit. The revelation that he’d become a sworn deputy while moonlighting as a mob hit man had caused significant embarrassment for the Cook County sheriff’s office. But that was nothing compared with the shame Gattuso had brought upon the underworld.

“His shoulders were slumped, his eyes were downcast,” recalls Margolis. “He just looked like a beaten, beaten, beaten pup.”

Aiding in Margolis’s efforts to turn him was a remarkable discovery: An attempted hit on Gattuso inside the MCC had been unearthed. A weapon had even been found: a shiv fashioned from the metal sheathing of an air conditioner, Margolis recalls.

The prosecutor returned to the interrogation room and showed Gattuso the savage-looking jailhouse knife. Margolis was blunt: If Gattuso didn’t cooperate, the mob would get to him eventually.

Margolis felt he had made his case as best he could. But while Ken Eto had been calculating even in his hospital bed, weighing his odds of survival, Gattuso seemed to lack such analytical instinct. “He just didn’t have the courage to fix it,” says Margolis. “He just didn’t have the courage to turn his back on the people that he lived with for decades, that way of life.”

It was all Gattuso had ever known. And it would be what he would return to — for better or worse — following another surprise development: Campise and Gattuso were being released on bond. “Organized crime affiliates were raising money and posting some houses, relatives’ houses and the like, to help satisfy the bond,” explains Margolis.

It was what the Outfit wanted. Gattuso was a free man again, a walking target. Out on the street, he visited an associate on the North Side. Chuck Renslow, a famed photographer and pioneer of gay Chicago nightlife, had long operated a series of leather bars in Caesar DiVarco’s territory, kicking up the requisite tax to Gattuso, his main Outfit contact. But during this visit, as Renslow would later recall to a biographer, it was clear that “something was wrong.”

Gattuso explained to Renslow that he had been tasked with killing Tokyo Joe, the gambling boss, and had mucked it up. Sitting across from his unlikely confessor, an exhausted Gattuso told the founder of the International Mr. Leather competition where he thought it was all heading.

As Renslow recalled: “He said, ‘I won’t be around too long.’ ”

Now back in Chicago, Elaine Smith was getting up to speed on Operation Sun-Up. Eto’s account of the weeks that preceded the shooting presented tantalizing indications that Big Joe Arnold and Caesar DiVarco had been intimately involved in setting him up. The parking ticket had even provided a bit of corroborating evidence, confirming Eto had been near DiVarco’s club the day he’d ordered him to dinner with Vince Solano.

Whether or not Gattuso or Campise talked, Smith and her fellow agents hoped more physical evidence could do some talking for them. Eto’s Torino had been sitting in a police garage since the shooting but had not yet been examined for forensic evidence. That was where Smith would start. Just what evidence might be gleaned, however, was unclear. Eto had said both Campise and Gattuso had worn gloves; fingerprint analysis would be fruitless. No shell casings had been found in the car, indicating a revolver had been used, but no such weapon had been recovered, making ballistics evidence a likely dead end. A search for clothing fibers probably would be futile since Gattuso and Campise had no doubt discarded the suits and winter jackets they wore that night.

That left one other type of trace evidence. Campise had sat in the front passenger seat; Gattuso, in the rear, on the driver’s side. Loose hairs, if recovered from the headrests and cushions, could be compared against samples plucked from Campise and Gattuso when they were in FBI custody.

While FBI technicians tore apart the Torino in a federal lot, painstakingly indexing and wrapping every part of the interior for analysis at FBI headquarters, Elaine Smith turned to what was still her greatest piece of evidence: Ken Eto himself. Eto was recovering comfortably within the secure confines of Naval Station Great Lakes, about 20 miles north of Chicago. He had an entire medical ward to himself, surrounded by 20 vacant beds and a sweeping view of Lake Michigan.

Steve Eto, accompanied by FBI agents, was flown in to visit his father at his bedside. Ken Eto reassured his son, by then a young man living in Minnesota, that he was recovering well — and would be taking his revenge against the people who’d done this to him. “Well, you’re gonna hear a lot of things, that I turned rat,” Ken told him. “I gave them their chance. So now it’s my turn.”

Round-the-clock FBI protection within a U.S. Navy installation ensured that even the most nefarious Outfit hit men would be unable to get to Eto. It also gave the feds a safe haven to begin quizzing the mob figure on more than three decades of underworld history — the potential germ of many more investigations to come.

While Smith was on vacation in Colorado, two other agents had taken the lead on debriefing Eto. But as the one who had first busted him, and the one he had asked for from his hospital bed, Smith had a unique relationship with the bureau’s newest cooperator. And this time, she’d be speaking to him as an ally.

Smith would describe this first exchange in her memoir. She approached Eto, who was reading a newspaper in bed.

“So you remember me, Mr. Eto?” she asked.

Eto removed his reading glasses. It was his first time seeing her since that day in the Chicago FBI office. “How could I forget?” he said. “You run the show!”

Sitting down at his bedside, Smith found Eto in good spirits. “I guess you got what you wanted, huh?” he said.

Hardly, Smith adamantly assured him. She’d never wanted it to happen this way, for him to come so close to death. How had that happened, anyway?

The two made their way down the hall, where they settled into chairs to discuss it all: the fuss over the lease, that uncomfortable walk he’d taken with Vince Solano, the first gunshot. Talking that afternoon, Smith also received a crash course in just how massive, sleek, and powerful the Outfit was — and how thoroughly it had corroded public institutions in Chicago. Eto was insistent: No less an official than William Hanhardt, the chief of detectives for the Chicago Police Department, had been Outfit property for decades.

And the Outfit’s influence extended far beyond Chicago. A machinery of payoffs had ensnared police officials, judges, and a multitude of political operatives at the local, state, and national levels, Eto explained. The Outfit’s downtown “Connection Guys,” as they were known, had enabled mass exploitation to make a few men rich, allowing monstrous acts of violence to go unpunished.

As they shared a pot of terrible coffee, Smith eyed the mob boss sitting across from her in slippers, a bathrobe, and a halo of gauze. She asked why Eto had gone to the dinner appointment, knowing it was likely a setup.

“I thought maybe there was a small percentage of an edge, but very small, and I had to take it,” he answered. “For me, I had no other choice, but once Jasper directed me to the alley, I knew it was all over.”

Now, perhaps, the Outfit would be taken for a one-way ride, too.

On July 14, 1983, a resident of the Pebblewood Condominiums complex in Naperville noticed a blue-silver 1981 Volvo parked in the space next to his own. He was sure it had not been there the day before. Normally, he would have ignored it, but something smelled awful — and it was coming from the car.

Two days earlier, sometime around 9 a.m. on Tuesday, July 12, Jay Campise left his wife, Josephine, at home in River Forest to make arrangements for a wake. He’d planned to meet his brother at the chapel where they’d be laying out a family friend, and then he might head to the antiques store he’d kept as a front for years. Around the same time, about 11 miles east, Johnny Gattuso left his wife, Carmella, in Little Italy to pick up some materials for the drywalling he was doing in their apartment.

The Outfit was sending a message, leaving the corpses somewhere so public. They had wanted the car to be found.

In the five months that they had been free on bond, Ken Eto’s assailants had avoided each other, working on the assumption that it would be their best insurance policy: Should one go missing, they figured, at least the other would have a sporting chance of making it to the police. But then, the previous Thursday, prosecutors had disclosed to Campise’s and Gattuso’s attorneys, both longtime Outfit lawyers, a huge piece of pretrial discovery evidence. Hairs recovered from the front passenger and rear driver’s side seats of Eto’s Torino had been matched to their clients. It would not just be Eto’s word against theirs; the feds now had corroborating physical evidence.

Ultimately, it wouldn’t matter. Even before the cops got to the Volvo, they knew what they were going to find. Elaine Smith raced to the western suburb on her rare night off. When the police popped the trunk of Campise’s car, their suspicions were confirmed.

Jay Campise’s blue dress slacks were pulled down around his ankles. His blue jacket was hiked up to his armpits, revealing numerous stab wounds to his distended abdomen. His head looked like a gray basketball, with rivulets of blood dried across his face. He was missing his shoes. Johnny Gattuso was lying along the opposite end, his head at Campise’s feet. His white undershirt, stained brown with blood, had been forced up his torso as his stomach swelled from decomposition, revealing similar stab wounds. Gattuso’s face had turned black. A garrote was still wrenched around his neck.

Since Tuesday evening, when Gattuso and Campise had failed to return home, the Chicago area had been broiling in temperatures in the low 90s. With the victims swollen to a disgusting size by the heat, the responding investigators would have to wait to tow the car back to a police garage before attempting to scrape the dead mobsters out of the trunk.

The Outfit was sending a message, leaving the corpses somewhere so public. They had wanted the car to be found. Their choice not to use a firearm was a message, too; the deaths of Jay Campise and Johnny Gattuso had not been quick. The body of Gattuso, in particular, bore signs of torture.

His car would be found days later, parked near an Outfit-controlled adult bookstore — a racket associated with the North Side crew — providing the first fresh clue in the new murder investigation. But barring a break in the case, it was all speculation who’d done it. In Eto’s opinion, Vince Solano had not just ordered this double murder — he had almost certainly participated himself, perhaps killing the pair in his own home.

Smith wasn’t convinced Solano would be that reckless. But killing Campise and Gattuso so savagely sure felt like an attempt to save face. Prosecutor Jeremy Margolis, meanwhile, believed it likely that Gattuso had been lured to a meeting by Campise. FBI reports sent to Rome in the months before the pair’s deaths repeated concerns that at least one of the hit men might attempt to flee the country for Italy. Could a promise of safe passage have been a plausible enough ruse to draw Gattuso out into the open?

As for Campise, in all his arrogance, he very well may have participated in the attack, assured that killing Gattuso would be sufficient penance — right up until the knife was turned on him.

Upon hearing about it, even Eto had been surprised by Campise’s murder. He’d figured Gattuso was a goner but that Campise would likely get the pass from the Outfit that he had been so confident of receiving.

Darkly chuckling, he concluded that Vince Solano must have been really angry.

On April 22, 1985, a boogeyman appeared on the 25th floor of the Dirksen Building downtown. Wearing a pointed black hood, with holes cut out for two eyes and a mouth, and a flowing black robe, this strange and ghostly apparition was escorted to his seat before the President’s Commission on Organized Crime. Convened under extra-tight security for three days of hearings, the commission was eager to hear from Ken Eto, now a participant in the federal witness protection program, about his experiences with Laborers’ Union Local 1 official Vincent Solano.

Eto explained that Vince Solano tried to have him killed. The last time they had spoken, he said, “I just felt there was something wrong. He no longer trusted me.” The result of this distrust: “Bang! I got shot in the head.”

Solano, the most reticent of area crew chiefs in the Outfit, had been dragged into the sunlight. Brought before the commission after Eto’s testimony, he looked a bit like a disgraced bank examiner, slightly clammy in his conservative suit. While Eto had been so forthcoming on the stand, appearing to enjoy himself — drawing laughter and amazement in the room as he mimed playing dead in his Torino, wriggling his hands above his hooded head as he slumped over — Solano mostly stayed mum, pleading the Fifth multiple times, always in the same flat tone.

Solano would survive the public appearance relatively unscathed. The slayings of Gattuso and Campise had served their purpose, effectively insulating him from the Eto murder attempt. He was among the few Outfit honchos to escape the raft of prison terms seemingly ushered in by Eto’s cooperation with the feds.

Others weren’t so lucky. In Kansas City, Eto made another cameo appearance, sans cloak and mask, at the massive trial that had resulted from Operation Strawman. That federal probe into Mafia control of Las Vegas casinos had snared not just the leadership of Kansas City’s Civella family but four figures high up in the Outfit: Joey “the Clown” Lombardo, Angelo “the Hook” LaPietra, Jackie “the Lackey” Cerone, and, biggest of all, Joey Aiuppa, street boss of the Outfit, the man who’d likely given the final OK to kill Ken Eto. All were convicted and sent to federal prison.

The Chicago Outfit, insofar as it still exists, is a ghostly presence, reduced to a small-time existence on the margins of the city.

Eto would help close more cases, too, including a homicide Elaine Smith had linked to the Outfit’s takeover of bolita in the 1950s and ’60s. Chavo Gonzalez had been abducted and murdered, his intestines hanging out of his belly, for throwing a pipe at LaPietra, then guarding one of Eto’s card games. Eto identified the four assailants.

The cocaine empire of a syndicate figure named Sam Sarcinelli became an even longer thread to pull; Eto’s description of how Sarcinelli invested the proceeds of his drug trafficking in Eto’s bolita racket was just the start. For years after Eto’s defection, Smith would pursue Sarcinelli’s finances, from Colombia to California and all the way to Manhattan. Taking part in a penny stock scheme Eto was familiar with, Sarcinelli had colluded with the Genovese family to launder drug money on the financial exchanges. The case eventually snared a slew of white-collar crooks, as well as Sarcinelli himself.

Besides Campise and Gattuso, however, no one would pay harder for the Eto bungling than Caesar DiVarco, once the gangster-turned-informant’s direct superior. It would be a slow fall for Little Caesar. Sparing his life, the bosses were satisfied merely to strip the 72-year-old DiVarco of his status as a North Side boss. DiVarco’s old flunky, Big Joe Arnold, was elevated only briefly before he was imprisoned on charges of obstruction of justice — in a trial featuring the testimony of Ken Eto.

DiVarco’s excommunication was, in some ways, worse than death; he lost the only identity he had ever had, built over decades of skulduggery and sleaze. Deprived of power, DiVarco became a sick, lagging member of the pack.

In 1984, DiVarco was given the dubious honor of becoming a test case for the use of RICO statutes in Chicago. Consigned to federal prison, DiVarco died in the process of being transferred to testify before a probe in Washington D.C., an old man abandoned by the syndicate to which he’d given his life.

Which left Ken Eto the last man standing, somewhere in the witness protection program.

Today, at any time of night, on any day of the week, you can take a northwest-bound Blue Line train from the heart of the Loop to the Rosemont stop and there find a free shuttle bus to Rivers Casino in Des Plaines. Owned by the gaming conglomerate Churchill Downs Inc., the 44,000 square feet of table games and slot machines are operated by Rush Street Gaming, the firm of the billionaire real estate developer and major political fundraiser Neil Bluhm.

The downtown corridor of clip joints, gay bars, and somewhat sordid nightspots that gave Bluhm’s company its name has now virtually disappeared. As with the area’s porno theaters and adult bookstores, the out-call prostitution services professionalized in the postwar era by Tony Accardo have etherized over the internet, the madames of previous generations long gone. On the strip where Ken Eto operated, the old buildings are long demolished, replaced with the likes of the massive Waldorf Astoria and the streetfront façade of fashion house Marc Jacobs. The numbers and bolita rackets so expertly administered by Eto’s operation have faded, no match for the ubiquity of state lottery games.

With a large handle of around $20 billion wagered since the state expanded lawful gambling to sports betting in 2020, Illinois — and, more specifically, Chicago — is quickly becoming a hub for legal action. And nowhere will draw as much of it as Bally’s planned casino in River West. Between a slick downtown casino and the infiltration of sportsbooks into sacred venues like Wrigley Field, all this will likely demolish whatever illicit action remains on the street. The Chicago Outfit, insofar as it still exists, is a ghostly presence, reduced to a small-time existence on the margins of the city. Where once the Outfit’s tentacles stretched to Hollywood, today the largely geriatric mobsters struggle to hang on to crumbs.

On January 28, 2004, an obituary appeared in the pages of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution: Joe Tanaka, 84, of Norcross died Friday. The family will have a private service. Mr. Tanaka was a native of Livingston, Calif., and a restaurant owner.

Survived by his six children, “Joe Tanaka,” born as he was to the federal witness protection program, had died peacefully in an area hospice following a battle with cancer.

“He was more than just a mobster,” says his son Steve Eto, himself a father now, nearing the age his dad was at the time of his shooting. Big Joe Arnold — Uncle Joe, as Steve had known him — had approached the son shortly after his father’s disappearance into witness protection, offering $10,000 to betray his father’s location. But Steve refused, and his dad managed to elude the mob.

Steve had felt the full dimensions of Ken Eto in the years since his father had been freed from the Outfit. After driving to Minnesota to deliver a car to Steve, Ken had gotten to meet his grandchildren.

His Justice Department severance pay, secured by Elaine Smith, had been enough to finance a comfortable retirement. When Smith and her husband visited Eto in Hawaii, as she would recall in her memoir, her underworld gem had spoken to her as never before.

“I will forever be grateful to you Elaine, for all you have done for me. For all these years, you have been my friend and one of the few people I ever trusted.”

“My father thinks of you as a daughter,” added Linda, Ken Eto’s real daughter.

Eto had moved to Hawaii to live with Linda, and in beautiful Oahu in the mornings, he’d go fishing, as he always had, and drink his coffee with the other retirees at McDonald’s.

Later, after putting down more permanent retirement stakes in the Atlanta suburbs, he befriended a Latino immigrant family. The last photo of him, the only one he’d allowed to be taken by them, was at their daughter’s quinceañera. The smiling, grandfatherly man in the image — now over 80, sporting a dashing white mustache and twirling the birthday girl on a dance floor — still had Chicago mob bullet fragments under his scalp.

“He was my father, you know what I mean?” says Steve Eto, whose own son has a tattoo of the Chicago skyline emblazoned with two words: “Tokyo Joe.” “And I do love him and I do respect him.”

In his last years of life, if he drove past a river or lake, Ken Eto would park at the shoulder, pop the trunk, and haul his fishing gear to the water. There were no more bets that needed to be hedged in case a number hit. There was no more money to be made. There was just a bucolic river on a beautiful morning before the mosquitoes took full flight, a line to be dipped, and fish to be caught and thrown back.

No comments:

Post a Comment