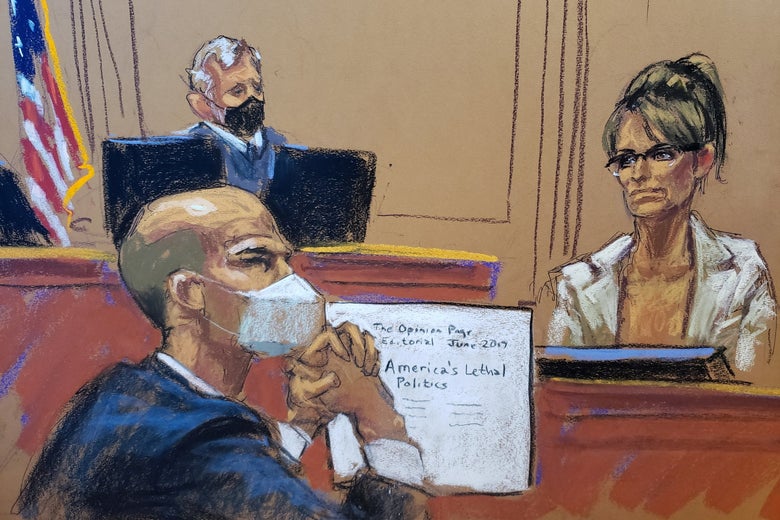

Sarah Palin took the stand this morning—on day six of her libel trial against the New York Times—clad in a black pencil skirt, cream boucle blazer, and megawatt smile. She delivered dollops of down-home charm. She was, at first, a compelling witness.

When she spoke about the deceased victims of the 2011 mass shooting that badly wounded then-Rep. Gabby Giffords, Palin was careful to say their full names and to convey the sadness she felt when she thought of their grieving families. She recalled that the 9-year-old girl who was murdered that day had been around the same age as her daughter Piper. In the courtroom, she displayed some of the gifts that had made her, for a time, a political sensation.

I admit, at this point in her testimony, I was a little impressed. Palin in no way resembled the caricature I had in my head. She was confident, articulate, and—somewhat to my surprise—quite lucid. I’m not saying she was Stephen Hawking, but she at least evinced a sort of horse sense, paired with grinning charisma, that you could imagine might make her an effective mayor or governor. Then, about a half-hour in, the wheels came off.

Palin’s lawyer tried to help her clean it up. Judge Jed S. Rakoff invited her to clarify what she meant. But Palin doubled down, saying, “My view was the Times took a lot of liberties” in the wake of the Giffords shooting and that the paper had “led the charge” against her back then. Confused looks sprouted on everyone’s faces. Reporters exchanged glances. Palin grew flustered, recognizing that something had curdled but not exactly sure what she’d screwed up. And here she reverted to the caricature: that fidgety posture and those looping, meaningless sentences. “I don’t have the specific references in front of me,” she said, desperately scrambling to recover.

The judge and all the lawyers seemed to agree, in what felt like silent assent, that an immediate sidebar had become necessary. They retreated to a separate room to hash things out in private. When they returned, everybody just moved on, with no mention of the previous flub. But the spell had been broken. Perhaps it was only a matter of time. I now remembered (and felt a little ashamed that I’d let myself forget) why Palin was, in her heyday, such a frequent figure of ridicule.

That first half-hour of testimony was sort of a microcosmic recapitulation of Palin’s 2008 debut on the national stage. When she gave her “hockey mom” speech at that year’s GOP convention, bringing down the house, it seemed like the vice presidential nominee might be a formidable force in politics for decades to come. Then—and it sure didn’t take long—she turned into a bumpkin pumpkin.

This was a good line. It was clearly one she’d prepped in advance. And it was, of course, a bit of an exaggeration. Palin isn’t the superstar she once was (only a handful of paparazzi waited outside the courthouse to photograph her this morning when she arrived with her reported beau, former New York Rangers hockey star Ron Duguay), but she still has more than a million followers on Twitter and more than 4 million on Facebook.

When a lawyer for the Times cross-examined Palin, he first asked whether that initial round of false accusations, back in 2011, had in fact hurt her reputation much. She acknowledged that she continued to make appearances on Fox News, and even signed a new contract with the network in 2013. She was also the featured character in multiple reality television shows.

Then the lawyer brought up The Masked Singer. Palin appeared on this prime-time show in 2020, well after the story she’s suing over ran in the Times. In the run-up to this trial, her attorneys filed a motion to bar any showing of the video in the courtroom. Now, Palin tried to bar any mention of the incident. “Objection,” she said, in an earnest way that made it sound like she actually thought she had the ability, as a witness, to object. The courtroom burst into chuckles. Rakoff informed her that this was a power not accorded to her. Forced to talk about the show, Palin said it was “the most fun 90 seconds of my life” and, when asked how much she was compensated, allowed that it had “paid some bills.”

Later, the Times’ lawyer asked what kind of mental anguish Palin had endured as a result of the publication of the Times editorial. She said she lost a little sleep, but admitted she’d never seen a doctor about it or taken any medication. She never hired a PR firm to restore her allegedly tarnished image. She’d also never consulted a pastor or a therapist. “I’ve never operated that way,” she said. “I holistically remedy issues that are caused by stress. Meaning running, hot yoga, those kinds of things.

Yesterday, I felt like James Bennet—who wrote the allegedly defamatory passages Palin is suing over, and is now co-defendant with the Times—failed to convey his contrition from the witness stand. Today, I felt Palin failed to convey her suffering. I’m sure it is no fun at all to be falsely accused of inciting the murder of, among others, a young girl. It must be horrible. But Palin didn’t really manage to get that across in her testimony. And by filing this lawsuit in 2017, just a couple of weeks after the Times piece ran, one might argue Palin actually gained more attention (and goodwill from right-wing partisans) than she would have otherwise enjoyed, as her political prospects shriveled and her star continued to dim.

At the end of the day, both sides rested. Tomorrow, we’ll hear their closing statements. And then this will all be in the hands of the jury. No pressure on them—it’s only, potentially, the future of American journalism that hangs in the balance.

No comments:

Post a Comment