Kimberly Mata-Rubio pulls her thick black hair into a ponytail, laces up her purple-and-black Brooks running shoes, and sets off on a three-mile loop through her hometown of Uvalde, at the edge of the Texas Hill Country, eighty miles west of San Antonio.

From her house, she heads west, then she makes a left and runs alongside the magnificent oak trees lining North Getty, one of Uvalde’s main streets. She runs past the softball fields where her ten-year-old daughter Alexandria “Lexi” Aniyah Rubio used to practice her hitting, past the two-story homes that Lexi used to dream of living in, past Julien’s, where Kim chose her dress for Lexi’s funeral. A few blocks away is First Baptist Church, where the funeral was held.

Just before she reaches the downtown plaza, Kim makes another left, on East Nopal Street, then makes a right and comes to a stop in front of a mural of her daughter, 20 feet tall and 23 feet wide, painted on the side of a brick building—one of 21 such murals spread throughout downtown depicting all the children and teachers who were slain in their classrooms at Robb Elementary School on the morning of May 24, 2022.

Lexi is wearing a wide-brimmed brown hat. She is surrounded by yellow sunflowers and blue butterflies, and she is smiling as if she doesn’t have a care in the world. Kim always makes a point of staring into Lexi’s eyes. “Lexi,” she says. Then she runs on, her breath steady, her slender arms pumping like pistons, and her Brooks shoes slapping against the pavement.

More often than not, Kim finishes her run as she began it, focused and with a steady breath. Occasionally, however, during the third mile, she begins to push herself too hard. A numbness comes to the hollow of her chest, and she lets her mind wander back to the day of the shootings—to her terrified little girl turning from a killer who was shooting children so quickly that they didn’t have time to scream. Half crying and half gasping for air, Kim will stagger home and fall into her husband’s arms.

When 19 children and 2 teachers are killed in a town of more than 15,000, the math works like this: You either loved one of the victims or you know someone who loved one of the victims—you know an aunt, a cousin, a close family friend. You know someone who tucked them into bed the night before, who argued with them about brushing their teeth, who told them to keep it down, who read them a story or maybe a poem and said goodnight, and then good morning, and then goodbye. This year alone, according to the Gun Violence Archive, there have been some 190 mass shootings in America. They have occurred everywhere—at a church school in Nashville (six dead); at a bank in Louisville, Kentucky (five dead); at a dance studio in Monterey Park, California (eleven dead); at a sweet sixteen party in Dadeville, Alabama (four dead); at a house in Cleveland, Texas (five dead), and on and on and on.

What is just as disturbing is that all of us seem to be growing numb to the horror. We receive news alerts about one shooting, then days later, perhaps hours later, another. It feels horrific but distant. There are now so many shootings that the math means we are, each of us, getting closer to that outer ring of victims, the ones who know the ones who loved the ones who died.

This is a story that starts on a day filled with hope and pride. On that May morning, Kim and her husband, Felix Rubio, walked into the cafeteria at Robb Elementary School to watch Lexi participate with her fourth-grade classmates in their end-of-the-year awards ceremony.

Kim was then 33 and worked part-time as a reporter for the Uvalde Leader-News, the town’s twice-weekly newspaper, covering everything from city council meetings to the weather. Two days a week she drove to San Antonio, where she took history classes at St. Mary’s University. She was a shy, soft-spoken woman, “the kind of person who prefers to stay in the background,” she told me. In her free time, she liked reading—Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, Michael Ondaatje’s The English Patient, and Elie Wiesel’s Holocaust memoir Night were among her favorites.

Felix, who was 35, was a strapping man, five feet eleven and 210 pounds. He worked as a patrol deputy with the Uvalde County Sheriff’s Department, usually handling 911 calls. Like Kim, Felix was quiet and reserved. When they met in 2008, on MySpace, he already had a son from a teenage relationship, and she had a daughter and son from a teenage marriage. On their first date, they went to a Uvalde High School football game with their children. Less than a year later, they married at a justice of the peace’s office, ate cake at Kim’s grandmother’s home, and left with their children for a one-day honeymoon at San Antonio’s SeaWorld.

Over the next few years, Kim and Felix added three more children to the family. “You’ve put together a basketball team,” one of Kim’s friends told her. Now, in the spring of 2022, the six children—Julian, Lexi, Jahleela, David, Kalisa, and Isaiah—ranged in age from eight to eighteen. Kim and Felix were devoted parents. They were always up before sunrise to get the kids ready for school, and they picked them up in the afternoons to ferry them to sports practices and games. In the evenings, Kim fixed large family dinners—fettuccine Alfredo being everyone’s favorite—and on Friday movie nights, she served popcorn mixed with nacho cheese, accompanied by shots of pickle juice. The family squeezed onto two brown leather couches in the living room to watch comedies like Ghostbusters, The Croods, and Instant Family. They shared blankets, told jokes, and roared with laughter. “Everything we did was about family,” Kim told me. “Usually, when the kids had a birthday, they didn’t ask to have their friends come over. They preferred celebrating with their brothers and sisters.”

This was Kim and Felix’s second trip to the school after morning drop-off. Earlier, they had watched their youngest child Julian’s second-grade awards ceremony. Now they were back to see Lexi. Kim liked to call Lexi the family’s overachiever. She did her homework without being asked, made straight A’s, and starred on the girls’ basketball and softball teams. She often told her mom that she too planned to attend St. Mary’s, but to study math (her favorite subject) and then enroll at St. Mary’s law school after graduation so that she could one day become a lawyer and fight injustice.

“I used to tell Felix, ‘Lexi’s going to make a difference in this world,’ ” Kim said. “ ‘Just wait and see.’ ”

For her awards ceremony, Lexi was wearing a blue St. Mary’s hoodie, gym shorts, and white sneakers. She had her hair lightly streaked with caramel-colored highlights—a popular trend among girls her age in Uvalde. Her teacher, Arnulfo Reyes, presented her with both an A honor roll certificate and the Good Citizen certificate, and, as the ceremony came to an end, she had her photo taken with Kim and Felix.

It was at that moment, Kim would later tell me, that she had a feeling—“something like a mother’s intuition, a voice speaking to me,” she said—that she should withdraw Lexi from school for the rest of the day. Maybe, she thought, she would take her to the Dairy Queen for one of Lexi’s favorite treats, a mint-chocolate-chip Blizzard, to celebrate the end of another successful school year.

But Lexi was already headed back to her classroom. Kim called out to her, saying she’d pick her up that afternoon when school was out. Both she and Felix told Lexi “I love you.” Lexi turned around, gave her parents a smile, and then turned a corner and was gone.

Kim asked Felix to drop her off at the Leader-News, where she needed to finish a story about a new events space opening in town. The office was quiet. Only three other employees were at their desks. Kim turned on her computer and started writing.

Thirty minutes later, the police scanner in the office crackled to life. A dispatcher said gunshots had been heard on Diaz Street, just a few blocks from Robb Elementary. A few minutes passed. Then the scanner crackled again. The dispatcher said the elementary school had just been placed on lockdown.

Kim texted Felix, who was at home, having taken the day off work. “What’s happening at Robb?” she asked. He called his supervisor at the sheriff’s department but got no answer. He threw on his uniform, jumped into the squad car that he was allowed to keep at his home, and raced to the school. When he arrived, another officer pointed toward a low-slung, one-story classroom building on the west end of the Robb campus. Felix grabbed his rifle and ran that way.

By then, dozens of officers from different law enforcement agencies—the Uvalde school district’s police department, the Uvalde Police Department, Uvalde’s own sheriff’s department, the state’s Department of Public Safety, and the U.S. Border Patrol—were already at the building. Some were milling about outside, waiting for orders. Others were inside, scattered up and down the main hallway.

It turned out that the gunman was a troubled eighteen-year-old Uvalde High School dropout named Salvador Ramos who lived on Diaz Street with his grandmother. Earlier that morning, he had argued with her about his cellphone, shot her in the face, seriously wounding her, and then had driven her pickup toward Robb. He had crashed the truck into a ditch next to the school, emerged carrying an AR-15-style semiautomatic rifle and a backpack filled with ammunition, entered the school building through an unlocked door, headed down the hallway, burst inside one of two interconnected classrooms, Room 111 and Room 112, that were filled with fourth-grade students—and opened fire.

Felix made his way into the building and peered down the hallway. Footage from a security camera would later show another sheriff’s deputy standing behind Felix, gripping the back of his bulletproof vest, perhaps to make sure he didn’t dash down the hallway to try to save his daughter.

Although police officers had been taught in active shooter training to immediately hunt down the gunman and bring him down before he had a chance to kill more victims, a senior police official in the hallway that morning, Pete Arredondo, the chief of the Uvalde school district’s police force, was focused on acquiring equipment to enter the classrooms. (He later said he thought the shooter had barricaded himself in one of the rooms and was no longer an active shooter.) Arredondo’s hesitation, however, meant that wounded students and teachers were denied urgent medical care that might have saved their lives.

The standoff lasted for more than an hour. A few children dialed 911 on cellphones, whispering for help. Frantic parents, including Kim, began gathering outside the school. Even after the gunman let loose with another brief spray of gunfire, no order was given to breach the classroom doors.

Finally, at 12:50 p.m., 77 minutes after the gunman had first walked into the building, agents from BORTAC, a tactical unit of the U.S. Border Patrol that was based in the town of Del Rio, used a master key to enter Room 111. They saw the gunman standing in front of a closet, and they shot and killed him.

Other officers rushed into the two classrooms. Felix’s fellow deputy continued to hold him back. If Felix had been allowed in, this is what he would have seen: children and teachers sprawled on the floor, their bodies ripped apart by the high-powered gunshots. A doctor said one child had been decapitated by the force of the bullets. Another had a baseball-size hole in his chest. Blood was spattered on the walls and was sprayed over the fourth graders’ drawings and books and backpacks. The acrid odor of gunpowder hung in the air.

Felix was led out of the building, and another deputy drove him downtown to Uvalde’s civic center, which was where all Robb parents were being sent to learn the fates of their children. Kim met him there. They watched the yellow school buses arrive, one after another, filled with uninjured children who ran to their crying parents. Before they arrived at the center, Kim and Felix had learned that their son Julian had earlier gotten off a bus and was taken home by Kim’s father. As the afternoon wore on, however, there were fewer children getting off buses. And there was no news about Lexi.

At around 3 p.m., Kim and Felix decided to look for her themselves. One of Kim’s friends drove them to Uvalde Memorial Hospital, thinking Lexi might have been wounded and taken there. A hospital staffer told Kim and Felix that nobody matching Lexi’s description had come in. They then drove to a Uvalde funeral home where they had heard some students had been brought. But no students were there.

“Lexi still must be at the school,” Kim said to Felix. “We need to get there.” When employees at the funeral home, knowing the protocols around crime scenes, told Kim she wouldn’t be allowed near the school, Kim pulled off her flimsy leather sandals and started running. She sprinted barefoot toward the school, a mile away, the soles of her feet pounding the asphalt road. Bits of glass and gravel pierced her skin. But still she kept running, dodging traffic. Felix followed, trying to catch up to her, calling out Kim’s name.

Kim reached Robb’s main entrance and begged officers guarding the school to take her to Room 111. “Please, if Lexi’s in there, just let me sit with her,” Kim said. “All I want to do is be with her. I don’t want her to be alone.”

But the officers shook their heads. They told her the school was officially a crime scene. A fireman drove Kim and Felix back to the civic center, and they were eventually taken to the county attorney’s office. There, they were told that Lexi was among the dead.

Kim and Felix headed out of the office. They wrapped their arms around each other, and both of them began to sob. Kim could feel her feet throbbing.

They were so bloodied and bruised she could barely walk.

Within 24 hours of the massacre, Texas governor Greg Abbott held a press conference at Uvalde High School to announce that “evil” had come to Uvalde. Other politicians arrived to offer the impotence of their thoughts and prayers, as if checking off a box. Reporters flew in to knock on doors, trying to find someone who could explain why anyone would shoot up yet another school.

When a CNN correspondent and a camera crew showed up at the Rubios’ home, the entire family came outside and huddled together on the front porch. Everyone was weeping. The family showed the correspondent a photo of Lexi posing in that wide-brimmed hat. They also shared an image of Lexi throwing a ball at a softball game. Kim mentioned that Lexi wanted to go to law school, and Felix said Lexi dreamed of traveling to Australia.

In those first days after the shooting, Kim and Felix spent hours staring at photos of Lexi. They barely sipped water, and they ate so little that Kim’s mother, Cindy, a nurse, threatened to take them to the hospital and hook them up to IVs. They didn’t leave the house, and at night they lay in bed with their younger kids piled tightly around them. Because the kids said they were afraid of the dark, Kim and Felix kept the bathroom light on.

Neither Kim nor Felix slept for more than an hour or two at a time, and in the mornings, after the sun rose, they would get out of bed, walk into the living room, and stare at each other, wondering how they were going to make it through another day.

The truth was that everyone in Uvalde seemed overwhelmed with grief. In the downtown plaza, 21 white crosses were placed around the fountain, each bearing the name and photo of a child or teacher who had been killed. Another 21 crosses were erected on the front lawn of Robb Elementary, next to a brick sign that read “Welcome. Robb Elementary School. Bienvenidos.”

Day and night, townspeople and visitors placed stuffed animals, bouquets of flowers, rosary beads, balloons, Bibles, photos, and handwritten notes around the crosses. They held candlelit prayer vigils, listened to a mariachi band on the plaza perform “Amor Eterno,” and attended a memorial service at Uvalde’s indoor bull-riding arena. Pastors, speaking in turns in English and in Spanish, asked the audience sitting in the bleachers to keep trusting in God. “God still loves these little children,” one preacher proclaimed. “We don’t understand it, but he does.”

Aweek after the shooting, Kim received a call from a staffer with the U.S. House of Representatives’ Committee on Oversight and Reform. He said the committee was about to hold a hearing titled “The Urgent Need to Address the Gun Violence Epidemic,” and he was looking for residents from Uvalde and Buffalo—which also had just experienced a deadly mass shooting, at a grocery store—to testify. The staffer said he had been told by people who knew Kim that she would make a good witness. He asked if she would be willing to fly to Washington, D.C., to testify about Lexi’s life and death.

Kim wasn’t so sure she would make a good witness. Although she regularly voted, she had never before gotten involved in any political movement or social cause. Nor had she ever given a speech—“not once in my life,” she said. The idea that she would appear before a congressional committee in Washington made her stomach churn.

Over the years, however, Kim had complained to Felix about the dearth of gun control in America. It made no sense, she said, that an eighteen-year-old could legally purchase an AR-15—an exceptionally powerful semiautomatic assault rifle designed to be a weapon of war. Felix agreed with his wife. Like any cop, he had no interest in confronting a criminal with an assault weapon. Felix encouraged Kim to speak before the committee, and he promised to be right beside her as she did.

Kim told the congressional staffer that she wouldn’t be able to fly to Washington. She said they needed to stay in Uvalde to prepare for Lexi’s funeral, which was scheduled to take place only three days after the hearing. The staffer reassured Kim that she could speak to the committee over Zoom. “Okay,” Kim said. “I don’t know what I’m going to say, but I’ll do it.”

On the day of the hearing, the committee watched a prerecorded statement from Miah Cerrillo, a Uvalde fourth grader who had survived the carnage by covering herself in a classmate’s blood and pretending to be dead. She said she watched the gunman shoot her friends, her teacher, “and the whiteboard.” Her father spoke next, telling the committee that Miah hadn’t been the same since the shooting. Roy Guerrero, Uvalde’s sole pediatrician, testified about the children who had been brought to the hospital that day, their bodies “pulverized” by the killer’s bullets.

Then the video screens in the hearing room lit up, and there was Kim, sitting on one of the brown couches in her living room—the spot where Lexi had sat on Friday movie nights. Kim wore a black sweater, and her dark, waist-length hair was carefully brushed back behind her ears. Felix, wearing a button-down khaki shirt, sat closely beside her.

Kim stared at a printout of her speech that she had written and rewritten on her laptop the night before. She took a breath and began to read. With a shaky voice, she told the lawmakers about Lexi, describing her as “intelligent, compassionate, and athletic.” Kim also recalled the moment after the fourth-grade awards ceremony when she and Felix had said goodbye to Lexi. “We told her we loved her, and we would pick her up after school,” Kim said. “I left my daughter at that school, and that decision will haunt me for the rest of my life.”

Because of the tears pooling in her eyes and blurring her vision, Kim was having trouble reading the copy of the speech she was holding. Kim said she recognized there would be intense opposition to any new law that would restrict ordinary citizens from obtaining the type of weapon that was used to kill Lexi. “We understand that for some reason, to some people, to people with money, to people who fund political campaigns, that guns are more important than children,” she said.

Nevertheless, she continued, the time had come to ban all assault rifles and high-capacity magazines. At the least, there should be a new law raising the minimum age to purchase such weapons from 18 to 21.

When Kim came to the last paragraph of her speech, she lifted her eyes and stared into the tiny dot of her laptop’s camera. “Somewhere out there is a mom listening to our testimony and thinking, ‘I can’t even imagine their pain,’ ” Kim said. But, Kim added, that mother needed to realize that the pain was not far away. Someday soon—perhaps very soon—another gunman might very well come barging into her own child’s school, brandishing an AR-15, mowing down everyone in his path.

“Our reality will one day be hers,” Kim said. She paused. “Unless we act now.”

Kim shut her laptop. “You did good, Babe,” Felix said, using his favorite nickname for his wife. But Kim was inconsolable. She was already thinking about Lexi’s upcoming funeral. “We’ve got to bury her,” she told Felix. “How are we ever going to get through that?”

Kim and Felix were not members of any religious congregation, but they had arranged for Lexi’s funeral to be held at Uvalde’s First Baptist Church, to accommodate everyone who wanted to attend. Kim asked those who were invited to wear bright colors because that’s what Lexi loved to wear. Kim wore a pink-and-yellow floral dress that a salesperson at Julien’s had given her for the occasion. Felix was in a yellow button-down shirt.

Lexi was dressed in her blue St. Mary’s hoodie, gray sweatpants, and tie-dye Crocs. The top of her child-size casket was decorated with paintings of sunflowers, butterflies, ice cream cones, a softball glove and bat, and a photo of Lexi. (SoulShine Industries, in the South Texas town of Edna, had donated customized caskets for nineteen of the victims.) Because the morticians were able to hide Lexi’s wounds—she had been shot in the back of her head—her casket was kept open during the service, giving the mourners a chance to see her one last time.

When the service began, Kim made her way to the pulpit and recited the famous e. e. cummings poem that she’d often read to Lexi. “I carry your heart with me (I carry it in my heart),” she began. “I am never without it (anywhere I go you go, my dear; and whatever is done by only me is your doing, my darling).”

An acquaintance of Kim’s, Vennessa McLerran, sang “You Are My Sunshine,” and after the benediction, everyone proceeded to the Hillcrest Memorial Cemetery, at the edge of town, to watch Lexi being lowered into the ground.

In the weeks that followed, every day—and sometimes twice a day—Kim and Felix went back to the cemetery to be with Lexi. On one trip, they brought a red oak sapling, barely five feet high, that they planted next to the grave so that she would have some shade during Uvalde’s brutally hot summer afternoons. Because they didn’t like the idea of Lexi having to be by herself in the cemetery at night, alone in the darkness, they strung solar-powered LED fairy lights around her grave that automatically switched on after the sun set. And on some of their trips to the cemetery, Kim and Felix placed Lexi’s favorite meal from McDonald’s on top of the grave: Chicken McNuggets stuffed inside a plain hamburger, which she used to call a “Lexiburger.”

“It’s still hard to believe she’s really gone,” Kim told me when I met up with her and Felix at the cemetery early one evening. “We still want to talk to her. We want to have dinner with her. When our oldest daughter, Kalisa, comes to the cemetery, she literally lays face down on Lexi’s grave. She whispers to Lexi that she misses her and that it’s time for her to come home.”

As we talked, other families began to arrive to spend time with their loved ones. One family sat on a blanket next to a grave, eating a picnic dinner. Another family brought their dog. Two little boys kicked a soccer ball, and another boy rode his bike with training wheels.

“It’s like you have your own little community out here,” I said to Kim.

“And none of us are going anywhere,” she replied as she watched Felix pour water from a plastic container onto their red oak. “We’ll all be coming out here for the rest of our lives.”

After her congressional testimony, Kim had no plans to make any more speeches. But in July, Javier Cazares, another Uvalde parent who had lost a child in the shooting, announced that he was organizing a march from Robb Elementary to the downtown plaza to protest both the inadequate police response to the shooting and the lack of what he described as “sensible” gun laws in America. He also asked family members of the victims, including Kim, to speak. In triple-digit temperatures, more than five hundred people participated in the march. When it came time for the speeches, Kim stepped up to the microphone, with Felix once again at her side. There was polite applause. “I want my daughter back,” Kim said. Her voice began rising. “If I can’t have her, then those who failed her will never know peace!” The protesters, many of whom knew Kim only as the quiet young woman who worked for the newspaper, let loose with a roar, the sound of their cheers echoing off the downtown buildings.

Days later, Kim sat down in an airplane seat for the first time. She and Felix had agreed to fly to D.C. so that she could speak at a rally put on by March Fourth, a nonprofit gun control group that was pushing for a ban on all assault weapons. Kitty Brandtner, the group’s founder, told me she had seen footage of Kim addressing the congressional committee, “and she was sincere, passionate, inspirational, and heartbreaking.”

Kim squeezed Felix’s hand as the jet lumbered down the runway, but within minutes she had stopped looking out her window and was working on a new speech, which she delivered the next day on the steps of the U.S. Capitol before a few hundred demonstrators. Kim said she had never stopped thinking about the morning Lexi was shot in Room 111. “I picture which side of the room she and her classmates huddled against as an eighteen-year-old man fired toward them,” she said. She also said she was haunted by “what if” questions regarding the shooting—namely, what if that Uvalde teenager had never been able to get his hands on an AR-15-style rifle in the first place. “I want that question to be the first thing to cross [the politicians’ minds] in the morning and the last thought they have before they go to bed each night. Because we are no longer asking for change, we are demanding it, and we are angry as hell!” Kim proclaimed. Just like in Uvalde, the crowd roared.

Kim and Felix then rushed to the airport so they could get back to San Antonio that night. They landed and drove directly to the Uvalde cemetery. It was the first time they had been away from Lexi for more than 24 hours. They saw the LED lights around her grave, flickering in the darkness.

“We’re here, Lexi,” Kim said. “We’re here.”

In mid-July, a few days after their Washington trip, a realtor showed Kim and Felix a two-story, four-bedroom brick-and-stone house that was in foreclosure in a neighborhood in north Uvalde. Since the shooting, they had been looking for a new place to live. One of their daughters, Jahleela, who was eleven, wouldn’t walk into the bedroom she had shared with Lexi. “The memories at home were too painful,” Kim said.

The new house needed repairs and a paint job, but Kim liked its location. It was in a neighborhood within walking distance of the public high school, the middle school, and another elementary school. Kim told me that if another shooter ever came into one of those schools, her children would be able to run home to safety.

“You worry about another school shooter coming to Uvalde?” I asked.

“Of course I do,” she said. “Every time I hear a police siren, I get panicky.”

Kim and Felix bought the home and were moving in by early August. They packed up not only their own belongings but all of Lexi’s clothes and shoes, her stuffed animals, her sports trophies, her basketballs, her softballs and softball gloves, her backpacks, her books and her journals. Kim even had Felix move Lexi’s bed and dresser from the old house and store them in the garage of the new house.

I assumed they would be giving all of Lexi’s items away. Kim, however, told me that as soon as one of the older children permanently moved out, she and Felix planned to turn his or her room into a bedroom for Lexi. “She always wanted her own room, and I now want to make sure that she gets one,” Kim explained. She looked at me and tried to smile. “I think Lexi will like that,” she said.

Although Kim quit her job at the newspaper, she did sign up to take four online history and criminal-justice courses for the fall semester at St. Mary’s, knowing that if she passed them all, she could graduate in December. She resumed the three-mile runs she’d been going on for a couple of years, pushing herself hard on the third mile even though she knew her anguish about Lexi’s killer might return.

And she did all of her usual domestic tasks, fixing breakfasts for the kids, dropping them off at their schools (which were now heavily guarded by police officers), doing the laundry, making beds, attending basketball and softball games, and once again cooking big family dinners.

By then, Felix also had decided to resign from his job, at the sheriff’s department. He’s a stay-at-home dad now. The bungled law enforcement response to the Robb shootings, he said, disillusioned him. He wanted to be home with Kim and the kids—to comfort them whenever they felt scared or unsafe or whenever they had one of their nightmares. Although Felix rarely opened up to outsiders (especially to reporters), those who knew him said he was deeply devoted to Kim. As Felix himself told me during one of our brief conversations, “Kim and I are joined at the hip. Whatever she wants to do, I’ll support her.”

And he did indeed remain Kim’s faithful, silent partner as she became one of the new advocates for gun control in America. Kim was regularly interviewed by reporters from NPR, the New York Times, the television networks, Time magazine, the Texas Tribune, and various Texas newspapers and television stations. She spoke at rallies organized by other gun control groups. In September she flew again with Felix to Washington, this time at the request of the prominent Newtown Action Alliance—named after the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School that killed 26 in Newtown, Connecticut—whose chairwoman, Po Murray, wanted Kim to meet Republican senators and push them to back off their positions opposing an assault weapons ban.

One of the senators Murray arranged for the Rubios to meet was Ted Cruz, Texas’s fierce opponent of gun regulations. Kim and Felix each wore a button with Lexi’s image on it. Cruz sat casually, with one of his trademark cowboy boots crossed over his knee. A staffer handed him a Diet Dr Pepper.

Felix pulled out his cellphone and showed Cruz a photo of Lexi in her casket. “That’s our daughter who was murdered at Robb Elementary.” Kim then said she and Felix hoped they could count on the senator’s support for an assault weapons ban. She was about to say more, but Cruz jumped in and told Kim and Felix about his own plan to stop school shootings: he wanted to put more law enforcement officers and more mental health services on school campuses.

A staffer gently interrupted the senator to say he had another appointment. The meeting had lasted less than five minutes, and Kim was not happy. As Cruz stood up to leave, Kim also rose, looked him in the eye, and snapped “You have no idea what you’re talking about, and I’m going to do everything I can to make sure you are not reelected.” Before Cruz had a chance to say anything else, Kim walked out of the office, followed by Felix. A spokesman for the senator later said the senator “saw firsthand” the Rubios’ “pain and grief.” But Cruz wasn’t changing his position on guns. In fact, the spokesman said, right after his meeting with the Rubios, Cruz went to the Senate floor “to fight for his school safety legislation.”

Kim was so dismayed by the meeting with Cruz that she began wearing a T-shirt—yellow for Lexi—with the phrase “You f@#ked with the wrong mom” on the back. She had a tattoo artist ink one of Lexi’s drawings of her and Lexi on her upper left arm, and she rolled up her sleeves so that anyone could see it. “The inaction of our political leaders is the reason my daughter is no longer here,” she told me. “And I am never going to let them forget that.”

On October 20, Lexi’s eleventh birthday, Kim and Felix invited friends and relatives to Lexi’s grave site. After their friends and relatives left, the family wrote messages to her on sticky notes, applied the notes to helium-filled balloons, and then released the balloons into the air.

On the evening of November 2, Kim, Felix, and their family gathered again at the cemetery for el Día de los Muertos, the Day of the Dead, the annual holiday that symbolically reunites the living and the dead. Kim and Felix set up an ofrenda, a decorated folding table that served as an altar, filled with keepsakes that reminded them of Lexi, from her lavender water bottle and her softball glove to a plate of fettuccine Alfredo from an Olive Garden in San Antonio, one of Lexi’s favorite restaurants. Townspeople strolled past the grave and said hello to the Rubios. Arnulfo Reyes, Lexi’s fourth-grade teacher, who was shot in the arm, placed a chocolate candy bar for Lexi on the ofrenda. A mariachi band that played contemporary music showed up to perform its version of “My Girl.” Kim, who had spent the evening greeting friends and trying to make small talk, took a seat on a folding chair and stared silently at Lexi’s grave as the song came to an end.

The next day, sitting with Kim at her kitchen table, watching her eat a gordita, I asked how she was dealing with her grief.

“People always tell me that the grief will get easier with time, but so far it’s only gotten worse,” she said. Kim was silent for a few seconds. Then she said, “Some days I wish I wasn’t here. I wish I was with Lexi.”

“You actually hope your life will end on earth so that you can be with Lexi?” I asked.

There was another silence. “Yes,” Kim finally said.

“What does Felix say when you say that? Does he get worried?”

“Oh, he knows I’m not suicidal. He knows I would never do anything like that. But he understands. All parents who lose their children understand. It just breaks your heart to know that your child is gone—that she’s alone and that you will do anything to be with her.”

That fall Kim spent her free time going door to door in Uvalde, campaigning for Beto O’Rourke, the Democratic challenger to Abbott in the 2022 gubernatorial election. Abbott was another fierce opponent of gun regulations. He favored legislation that actually loosened restrictions on buying a gun. And he had plenty of supporters. To no one’s surprise, he clobbered O’Rourke on Election Day. Abbott even won a majority of votes in Uvalde County, which devastated Kim. “I wanted to send a message,” she posted on Twitter, “but instead, the state of Texas sent me a message: my daughter’s murder wasn’t enough.”

Kim wasn’t finished. “It doesn’t end tonight,” she wrote. “I’ll fight until I have nothing left to give.”

Not long after, Kim and Felix flew to Washington once again to attend the tenth annual National Vigil for All Victims of Gun Violence, which was held at the historic St. Mark’s Episcopal Church, a block behind the Library of Congress.

President Biden arrived and mentioned the people he’d lost, his wife and daughter in a car accident and, years later, his son Beau to cancer. “It’s like a black hole in the middle of your chest you’re being dragged into. And you never know if there’s ever a way out,” he said. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi also spoke, saying, “There’s no sound that is more painful in the world than to hear a mother find out that she has lost a child.”

One by one, survivors and family members of victims from mass shootings talked about loved ones they had lost. When it was Kim’s turn to speak, she walked slowly to the pulpit. “Lately, I see Lexi as if she is here,” she began, her voice quiet and measured. “Sitting next to me in the stands for her big brother David’s basketball game. Biting her nails in anticipation. Sitting in a front-row pew tonight, holding a candle, giving me a shy smile at the mention of her name.

“When I lay in bed, I turn on my side, envisioning her staring back at me,” Kim said. “I have one hand cradling her face. A thumb caressing her cheek. I kiss her forehead. Relish the smell of her hair. I want so badly to be a part of this alternative reality. But it doesn’t exist. This is my reality. Tonight, here, speaking at the tenth annual National Vigil for All Victims of Gun Violence because my ten-year-old daughter was murdered in her fourth-grade classroom.”

The next morning, she and Felix flew back to San Antonio. Three days later, back in San Antonio, they attended Kim’s graduation ceremony at St. Mary’s University. The Rubio children and much of Kim’s extended family were there. Felix placed a large photo of Lexi on an empty seat next to him. When Kim’s name was announced, everyone cheered as she walked across the stage in her cap and gown to receive her diploma.

It should have been a moment of triumph for Kim and the family. But during that same ceremony, the St. Mary’s law school graduates also received their diplomas. Kim felt her stomach drop. “I thought, ‘Why do they get to walk across that stage, and why will Lexi never get to do that?’ ” she said. “Why do we have to live with that?”

The Rubios headed home and made plans to start the holiday season. Felix normally decorated the outside of their home with blow-up Christmas characters: a snowman, a reindeer, a Santa Claus on a fishing boat. But this year he focused on Lexi’s grave, installing Christmas lights, oversized candy canes, ornaments, teddy bears, toy soldiers, and an artificial Christmas tree.

The family, of course, went out to the cemetery on Christmas Day. Kim had the kids open two wrapped presents that she had bought for Lexi: a sweatshirt and a stuffed, wide-eyed sloth. (Lexi had a great affection for all stuffed animals.) Kim put Lexi’s presents on her grave for a few minutes, and everyone wished Lexi a Merry Christmas.

“It was a sad day,” she said. “I’m afraid it will always be a sad day.”

On January 10, when members of the Eighty-eighth Legislature convened at the Texas Capitol, Kim, Felix, and other Uvalde parents who had lost children began driving to Austin every Tuesday to meet with those legislators, asking them to vote for a series of gun control bills—including one that would raise the minimum age to purchase assault weapons from 18 to 21—that had been filed by Democratic state senator Roland Gutierrez and Democratic representative Tracy King, both of whom represent Uvalde.

It seemed like an opportune time to get at least a couple of new gun laws passed. In early 2023 the country was going through an epidemic of gun violence. Already there had been 131 mass shootings in America in January, February, and March. (The Gun Violence Archive defines a mass shooting as one in which at least four people, not counting the shooter, are injured or killed.) On the morning of March 27, Kim’s cellphone buzzed just as she was wrapping up an interview with CNN about life in Uvalde after the shootings. Her mother, Cindy, was texting. She asked Kim if she had heard about Nashville.

Felix saw on his phone that someone had entered a private Christian school in Nashville and killed three 9-year-old children and three adults. It was a familiar scene: images of police cars and ambulances, frantic parents standing in the street, children holding hands as they were led out of the school’s front door. Kim looked at Felix and said, “Is this never going to come to an end?”

The next day, Kim and Felix made their weekly drive to the Capitol to lobby more state legislators. They came back the next week and the next. What became clear, however, was that Texas’s Republican politicians were not interested in passing any gun control legislation. During one debate on the Senate floor about the need to protect children from drag shows, Gutierrez asked his fellow senators if there were perhaps a greater need to protect kids from guns. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick quickly gaveled him down, demanding that he “stick to the topic of the issues that you’re asking questions on, or you will not be recognized in the future.” Gutierrez was so frustrated that he told reporters “Patrick and his Republican underlings right now are living in a fantasy land.”

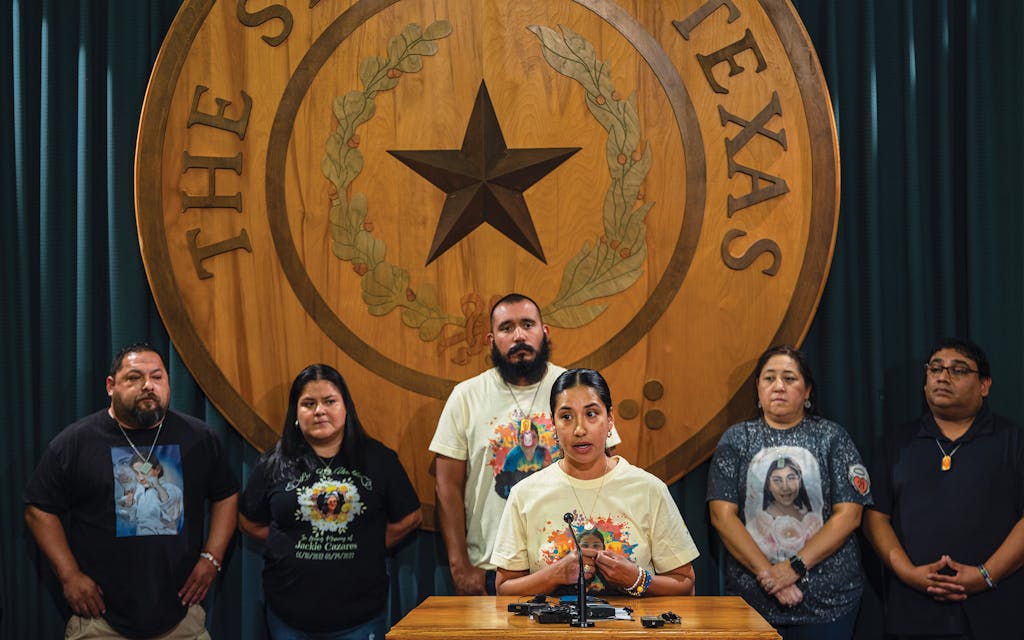

In mid-April, parents and relatives of the Uvalde victims were finally allowed to testify before a state House committee regarding the bill that would raise the minimum age to purchase AR-15-style semiautomatic rifles in Texas to 21.

“No action you take will bring back our daughter,” Kim told the legislators, crying through the three minutes she was given to speak. “But you do have the opportunity to honor Lexi’s life and legacy. I have hope that collectively you have the will, the courage, the judgment, and the strength to do what is just and right.”

Kim was hopeful that her speech would help get the bill voted out of committee. She and Felix stayed at the Capitol until after midnight and drove back to Uvalde the next morning, picked up their children, and went to the cemetery.

It was at least the 300th trip they had made to the cemetery since Lexi was buried, ten months earlier. While Felix poured water over the red oak sapling, Kim wiped the dust off Lexi’s tombstone. Then she and her daughters Kalisa and Jahleela lay down on the grave and sang “We Belong Together,” an old Ritchie Valens song that Kim would sing around the kids.

As night fell and the LED lights flickered on, the Rubio family headed home. Kim fixed dinner, made sure the kids got to bed, and then made a quick trip to Walmart to buy milk so that everyone could have cereal for breakfast. On the way back to the house, she stopped at an empty intersection. She kept her foot on the brake pedal.

At that moment, Kim later told me, she couldn’t stop crying. She said she felt an overwhelming need to talk to her daughter—to tell her how sorry she was for not protecting her, to let her know she would do anything for the two of them to be together again.

“Lexi, all I want is to be with you,” Kim said, her hands gripping the steering wheel.

For a few minutes she was silent, heartbroken that she heard nothing back. She headed to the house, walked inside with the carton of milk, and went to bed, hoping to get a couple of hours of sleep.

As always, the bathroom light was left on.

This article originally appeared in the June 2023 issue of Texas Monthly.

No comments:

Post a Comment