We scrambled over jagged rocks that lined the mouth of the cave, and stepped into darkness.

The craggy entrance gave way to an inky chamber, one with a padlocked metal door. It blocked access to a dizzying array of tunnels that snaked into and under a mountain of granite and limestone.

The expedition’s aim: to find a subterranean canyon where a tidal river washed over black sand fabulously rich in gold.

Headlamps flashed over damp sediment, illuminating a startling handwritten sign that alerted trespassers of something sinister.

“Bad air,” it read.

I eyed the warning warily, but the veteran miner leading our group explained that it was a fiction of his own design, one meant to keep out vandals and wildcatters.

The lock clicked open. We slipped past the sign.

This was Mt. Kokoweef.

The notion that there’s a mother lode beneath the California peak, which is about 100 miles northeast of Barstow, was popularized in the 1930s by a miner who claimed to have seen it during a daring, four-day voyage. But he and his contemporaries never extracted any treasure from the mountain.

These days, a different mining outfit is trying — on land it leases from a private company that owns the property. The miners are led by an 84-year-old who has spent more than half his life looking for the bonanza beneath 6,038-foot Mt. Kokoweef.

With funding from about 900 investors, he’s chasing what he believes is a $1-trillion strike.

The story of how a handful of 21st century “forty-niners” wound up searching for gold on a singed landscape studded with Joshua trees arcs back nearly 100 years, entangling an eclectic cast of characters. Among them is a surprising figure whose treasure map would, decades after its publication, jump-start a new adventure in the Mojave Desert. This one.

The tale of that man, his map, and the place it led to is really one about Southern California’s twin mirages — fame and fortune — and the people who seek one or the other. Or both.

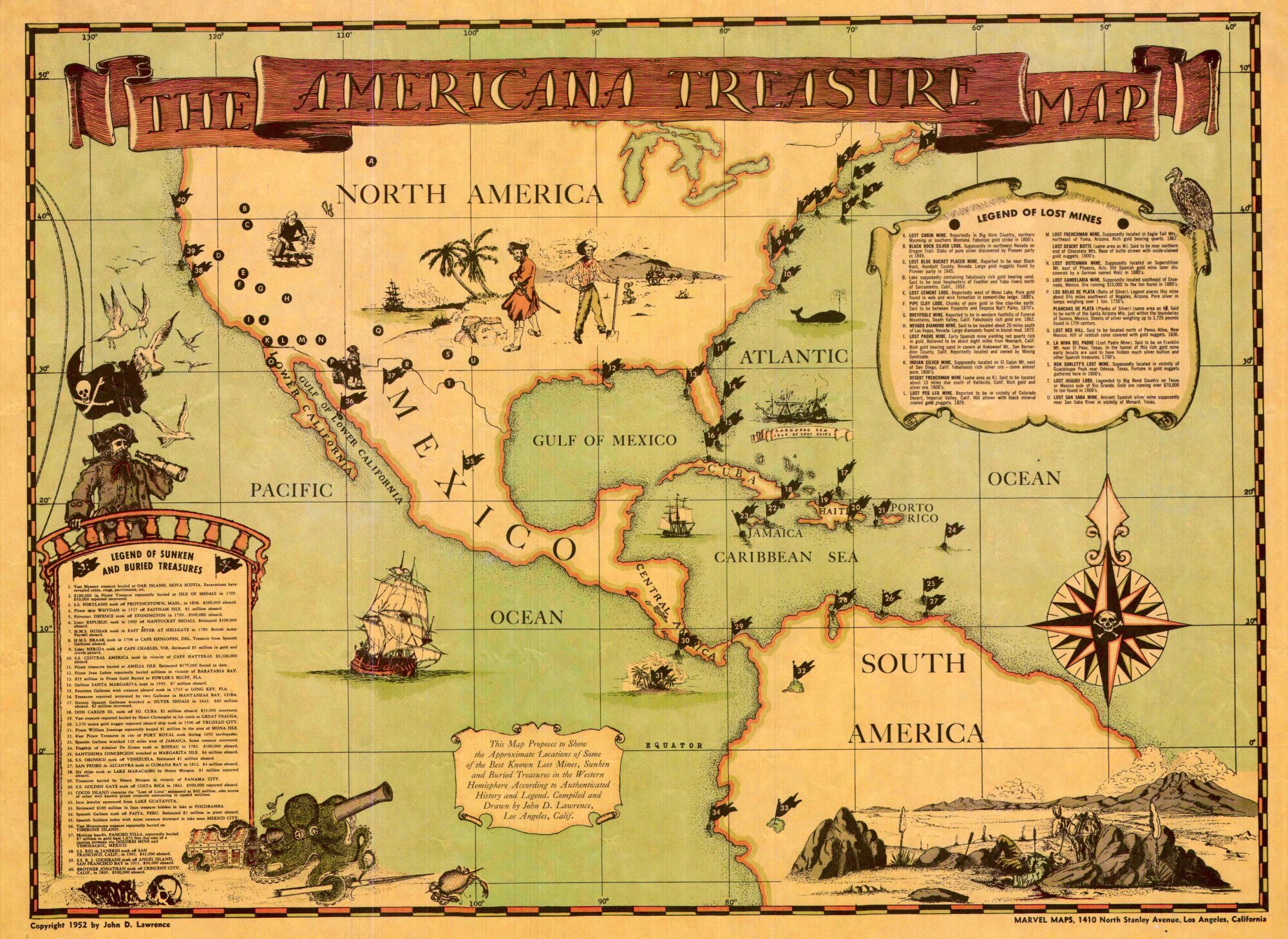

Printed on delicate yellow paper that was almost translucent, “The Americana Treasure Map” was decorated with drawings of galleons, pirates and a compass rose embellished with a skull and crossbones. It promised riches — and danger.

“This map proposes to show the approximate locations of some of the best known lost mines, sunken and buried treasures in the Western Hemisphere according to authenticated history and legend,” it proclaimed.

Published in 1952, the map highlighted 63 spots. Among its points of interest was a lost mine in Texas where Jesuits had hidden silver bullion, an island off Central America that was home to the $60-million “Loot of Lima,” and, of course, the abundant “gold bearing sand” of San Bernardino County’s Mt. Kokoweef.

Enchanted by its suggestion of swashbuckling adventure, I acquired the map in December 2019. One day in April 2020, I found myself staring at it, lost in the intricacy of the artwork, when something printed on the bottom right corner caught my eye: “Marvel Maps, 1410 North Stanley Avenue.” That was just a few miles from where I lived. In another corner was a man’s name: John D. Lawrence.

Lawrence, I’d soon learn, had been a mapmaker, actor and Hollywood executive. He hailed from Utah and dreamed of making it in the movies, and eventually carved out a decades-long career in Tinseltown.

He died nearly 50 years ago, but the actor’s relatives could still easily summon gilt-edged memories of him from their teenage years. Lawrence, it seems, made an impression.

“Dark hair, mustache, looked like he could’ve been a movie star but he never was,” said Steve Retter, a nephew.

Bill Retter, another nephew, has a copy of one of Lawrence’s other maps — “Ghost Towns of the Old West” — hanging in his home.

“He would investigate, did all the artwork,” Retter said.

But a question loomed: Did Lawrence’s treasure map actually lead to a trove?

His relatives didn’t know the answer, but they knew this: Lawrence had been a treasure hunter. “I think he was — in his own right,” said Donna Retter, a niece. “He spent a lot of time in the desert.”

The map featured only one local point of interest in a desert: Mt. Kokoweef.

Talking to Lawrence’s kin piqued my curiosity about the man behind the map.

Born in Salt Lake City in 1910, Lawrence made his way to L.A. by 1935, according to U.S. Census Bureau records, and, as of 1940, was an actor working in L.A.’s “picture industry.”

One of his first film roles came in 1939’s “Of Mice and Men” in the uncredited part of a ranch hand. That was the sort of work he typically landed, mostly appearing as an extra.

Lawrence’s Screen Actors Guild records indicated that he served two years in the U.S. Merchant Marines during World War II and was discharged in March 1945. Lawrence would publish “The Americana Treasure Map” seven years later.

‘Dark hair, mustache, looked like he could’ve been a movie star but he never was.’

— Steve Retter, nephew of John D. Lawrence

The mapmaker was something of a Renaissance man — relatives said he pursued photography, worked as a chauffeur and served as an executive with the Screen Extras Guild, then a union for background actors. He did it all while cutting a suave figure. “He was like a Frenchman who would kiss your hand — he was just amazing,” Donna Retter said.

That charm must have worked on the woman for whom Marvel Maps was named.

Marvel Retter was born in Wakefield, Kan., in 1914. According to family lore, Marvel and Lawrence met while she was working at a relative’s fruit stand. He was passing through Kansas on his way to the World’s Fair in Chicago, which began in 1933.

“Uncle John came through, and [took] one look and was smitten,” Steve Retter said.

Lawrence made a promise to Marvel: “I’m going to be back.”

They married in L.A. in 1936.

Like her husband, Marvel built a low-profile career in Hollywood, though her fame would eventually eclipse his. She had a stint with “The Andy Griffith Show” in the 1960s, working in the costume department and regularly appearing as an uncredited background character known among fans as “Nice Dress Nellie.” Devotees of the comedy spent years trying to identify her until 2020, when a crew member helped them solve the mystery.

“She’s in it so much — she deserves recognition among fans,” said “Andy Griffith Show” aficionado Randy Turner of Liberty Township, Ohio, who assisted in uncovering the actor’s name.

Though the Lawrences never achieved stardom, they managed to brush up against greatness.

The couple became close friends of Julian Eltinge, a vaudeville luminary who also starred in silent pictures. They lived with Eltinge for a time at his Silver Lake estate, Villa Capistrano, an ornate Spanish Colonial Revival property built for the actor. They resided there starting in 1936, according to a story in the Salt Lake Telegram, Lawrence’s hometown newspaper.

Eltinge was famed for his female impersonation, which prompted questions about his sexuality, though the actor presented himself as heterosexual.

Judy Retter, a niece, said that Marvel had, in conversations with her, insinuated that Eltinge was gay — and that she played a role in the actor keeping up appearances, accompanying him to social events where they “appeared as a couple.”

“She was happy to … help him with his life in Hollywood,” Retter said of Marvel, who died in 2000.

In a nod to Eltinge’s apparent desire for privacy, Villa Capistrano looks to have been constructed so as to not be seen. Shrouded in greenery high above the Silver Lake Reservoir, it was once likened to an “impregnable fortress” by Architectural Record.

Indeed, the mansion’s seclusion in a teeming city has always been its defining feature. Perhaps Villa Capistrano could reveal something about Lawrence.

The brick stairs knifed past a garden, where lizards darted among eroded stone sculptures and palm trees wore their dead fronds like mangy beards. With each step, more of the weathered hillside mansion was revealed.

Built in 1918, Villa Capistrano had seen better days — the pink house’s trim was peeling and some of the Spanish roof tiles were missing. Still, there was a kind of beauty in the decay.

Sitting at a table near the top of the stairs, owner Charles Knill gestured past an archway that framed the reservoir. “That,” he said, “is a favorite view.”

Over the years, Knill had collected Eltinge memorabilia including film posters displayed inside the villa. His cache also contained items related to the Lawrences, among them a 1939 L.A. Examiner story that featured a photo of Eltinge and a beaming Marvel walking arm in arm.

Villa Capistrano had once been host to many glamorous soirees, including the Lawrences’ wedding.

The Salt Lake Telegram reported that they had married in a ceremony that featured music by a renowned Tin Pan Alley composer. Marvel wore a pink chiffon dress and carried carnations. Her father had died in the 1918 flu pandemic, leaving a void in her wedding party. So, the story said, “The bride was given in marriage by Mr. Eltinge.”

Knill couldn’t offer any insight into Lawrence’s treasure map. That left one place to find out the truth of it. I decided to venture to Mt. Kokoweef.

My guide there would be Steve Bisyak, camp manager for Kokoweef Inc., which operates the mining concern at the mountain. The outfit is following the path of Earl Dorr, who, in 1934, claimed to have explored more than eight miles of caverns beneath the peak, including a vast underground canyon where a river flowed.

Dorr, whose story earned newspaper coverage in subsequent years, claimed the sand there was “very rich in placer gold.” The canyon ledges, he attested, were too. The website for Kokoweef Inc. said that Dorr sealed the entrance to the caverns to protect his find, intending to return later. However, the site said, “circumstances made that impossible.” (One explanation for Dorr’s inability to access the caves again: He didn’t hold a mining claim there.)

Among treasure seekers, Dorr’s tale became fairly well known, prompting others to try their luck at the mountain, including members of Kokoweef Inc.

I told Bisyak about Lawrence. He immediately had a thought: “Crystal Cave ... that’s where this guy was probably focused because that’s where Earl Dorr said he went.”

We made plans for my visit to Mt. Kokoweef — access is by appointment only — and I asked Bisyak how things had been going there. “We are not at the river yet, but we are working on it,” he replied.

The no-nonsense explorer said this with a matter-of-fact confidence, and it took a moment to realize which watercourse he was referencing.

He meant the mythical lost river of gold.

Larry Hahn had a vision. And the president of Kokoweef Inc. — who has been prospecting at the peak since 1977 — wanted to share it before I left with Bisyak and two other miners to explore the mountain’s system of tunnels.

Hahn, who created Kokoweef Inc.’s predecessor company in 1985, said he would use proceeds from his hoped-for $1-trillion gold strike to develop the area into a resort. The 1-million-square-foot domed facility would feature restaurants, bars, theaters and jewelry shops. A bullet train would ferry 100,000 visitors daily to and from Las Vegas for just $1 per ride, said Hahn, who operates a military surplus store there.

But doubters — among them geologists — say there’s no lode beneath Mt. Kokoweef.

“There are a lot of naysayers who think nothing like that can exist,” acknowledged Hahn, who noted his company has spent about $2.5 million — funds raised by selling shares in Kokoweef Inc. to investors — trying to find the treasure. “Everything we have done … says it is there.”

I set out for the mountain with Bisyak and the others in a utility vehicle that jostled past dramatic peaks and otherworldly vegetation. Carrion birds circled over sun-bleached expanses. The land seemed to have a sinister edge to it — one that was confirmed by Bisyak when he spoke of the MS-13 traffickers who slip through the area, along with the deadly Mojave green rattlesnake.

“This is exploration,” said Bisyak, who’s been mining at Mt. Kokoweef since 2010. “This is detective work.”

Before long, we rumbled to a stop. We put on our headlamps and approached an entrance to the tunnel network that had been blasted out of solid rock about 50 years ago. That work, Bisyak said, followed the efforts of a mining syndicate that had found zinc ore here, but no gold.

Flushed with light from the headlamps, a tunnel began to reveal itself. A bat clung to the ceiling. An old, empty can of Modelo Especial lay on the ground. A rusty miner’s lamp and a pack of Marlboro Southern Cut cigarettes were strewn on a dirty table.

We went deeper. Mud streaked with mining muck clotted the soles of our boots. We passed open shafts, some unmarked. Bisyak asked half-jokingly if I wanted to venture down one.

“It’s not like it’s forever,” he said. “Might have water at the bottom.”

This was unsafe. But it was also exhilarating. And the through-line from Lawrence to the explorers of Kokoweef Inc. was evident. They were all dreamers.

I asked if I could visit the area Kokoweef Inc. was actively prospecting, but Bisyak demurred, citing the need for secrecy.

As we hiked out, I found myself looking back — just for a moment — into darkness. The answer to the question that had animated this adventure would not be found here.

Edging away from Kokoweef Inc.’s camp under darkening skies, I headed for the interstate thinking about Lawrence. His story was a strange mix of surprise and disappointment.

Lawrence died in 1974. He was 63. He suffered a heart attack while changing a light bulb in the home of former Miss Nebraska Berniece Graf, the mother of “The Fugitive” star David Janssen, according to Denny Retter, a nephew.

Lawrence’s map had spurred a quest — a fact that might have pleased him — but it hadn’t revealed a lode.

Days later, though, Turner, the “Andy Griffith Show” expert, helped me make sense of the journey. He admitted that he had harbored mixed feelings about identifying Marvel as “Nice Dress Nellie.”

“The anticipation is almost more fun than knowing,” he said. “You almost don’t want to get it resolved. I like the idea that there is some mystery — there are things we may never know.”

Maybe Lawrence just loved mysteries and learned how to hone his fictions in Hollywood. Or maybe he really knew something about treasure. Either way, visiting Mt. Kokoweef hadn’t settled the matter.

Still, Lawrence had mapped 62 other locations scattered across the Americas that were potentially hiding vast riches.

But my hunt ended here.

Because there was a chance that knowing more of John D. Lawrence’s story might diminish it.

Better that his map retain its secrets.

Times researcher Scott Wilson contributed to this report.

No comments:

Post a Comment