Benedict's resistance to what he saw as campaigns to secularize the church, promote women as priests and "normalize" homosexuality led to his characterization as “God’s Rottweiler.”

Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, the Bavarian-born theologian whose conservative Roman Catholicism earned him the nickname “God’s Rottweiler” and who shocked his flock by suddenly resigning the papacy after just eight years, died Saturday, the Vatican said.

He was 95.

Benedict was the longest-living pope, having surpassed Pope Leo XIII in September 2020.

“With sorrow I inform you that the Pope Emeritus, Benedict XVI, passed away today at 9:34 in the Mater Ecclesiae Monastery in the Vatican,” the Vatican said in a statement early Saturday. No cause of death was provided. "Further information will be provided as soon as possible,” the statement said.

The Vatican said Benedict’s remains would be on public display in St. Peter’s Basilica starting Monday for the faithful to pay their final respects.

Benedict, the first pope to voluntarily give up the pontifical reins in nearly 600 years, spent his twilight years living at the Vatican in a refurbished monastery, rarely appearing in public with the man who replaced him, Pope Francis.

But he continued to advise his far more liberal-minded successor in private. His influence was felt in August 2016, when Francis, who had made attempts to reach out to the LGBTQ community, took an unexpectedly hard line against schools’ teaching children that they could choose their gender.

“We must think about what Pope Benedict said — ‘It’s the epoch of sin against God the Creator,’” Francis said at a gathering of Polish bishops.

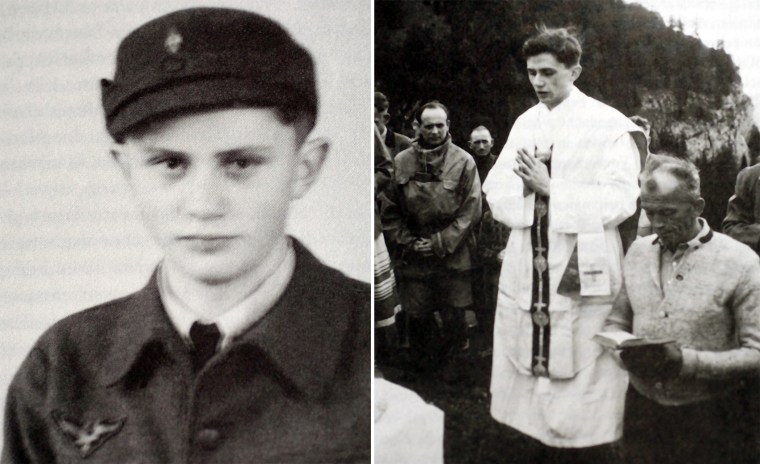

Born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger on April 16, 1927, in Marktl, in Germany, Benedict, the son of police officer Josef and Maria, grew up in a Germany infected by Nazism. Like his father, Benedict opposed Hitler. But at age 14, he was forced to join the Hitler Youth. And two years later, while still in the seminary, the future pope was conscripted into the German army and sent to the front.

With the Allies on the verge of victory, Benedict deserted and went home. After a brief stint in a POW camp, he returned to the seminary and, along with his brother Georg, was ordained a priest on June 29, 1951.

Unlike most priests, Benedict logged little time in parishes. Instead, he embarked on an academic career and found himself moving to the conservative right as German campuses moved to the liberal left in the 1960s.

Unlike the wildly popular John Paul II, Benedict was a stern and forbidding figure with little of his Polish predecessor’s charisma. He was seen more as a transitional pope — a keeper of John Paul’s flame.

Like John Paul, Benedict was a witness to the Holocaust and made it his mission to reach out to Jews and to fight antisemitism. In 2008, Benedict became the first pope to visit a Jewish house of worship in the United States when he prayed at the Park East Synagogue in New York City.

Benedict also made a historic pilgrimage to ground zero in New York City, where he prayed with the families of the victims of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001.

Benedict was considered a dominant intellectual figure in Roman Catholicism as he moved toward more conservative positions in the 40 years before he assumed the papacy. By 1981, he had become the prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, the council — known during the 16th century as the Spanish Inquisition — that promotes and enforces church doctrine.

His fierce resistance to what he saw as campaigns to secularize the church, promote women as priests, "normalize" homosexuality and encourage a liberal Latin American strain of Catholicism known as liberation theology led to his characterization as “God’s Rottweiler.”

Among his more consequential actions as prefect was to issue a formal letter in May 2001 that was widely interpreted as declaring that investigations into allegations of clergy sex abuse were confidential church matters not subject to review by civil law enforcement agencies. Critics — and attorneys for victims of such abuse — often pointed to the letter as proof that the church was seeking to cover up the burgeoning scandal.

The fallout dogged Benedict from the beginning of his papacy. In 2005, his first year as pope, he was accused in a lawsuit of having personally covered up a priest’s abuse of three boys in Texas. He avoided the lawsuit by requesting and receiving diplomatic immunity from the State Department.

“He could go around and minister to victims, which he did, and I think that was a brave and profound thing to do, but he couldn’t change the definitive elements of the Catholic Church that enable abuse,” said Michael D’Antonio, author of “Mortal Sins: Sex, Crime, and the Era of Catholic Scandal.”

Benedict asked for forgiveness in February for any “grievous faults” in his handling of clergy sex abuse cases, but denied any personal or specific wrongdoing after an independent report from a German law firm criticized his actions in four cases while he was archbishop of Munich.

Benedict’s conservatism extended to the church’s public face. In addition to his native German, he was fluent in Italian, French, English and Latin — the last of which he sought to revive in church ceremony.

In 2007, he issued an official document allowing performance of the Tridentine Mass, also known as the Traditional Latin Mass, in the European and North African countries whose histories had been shaped by Latin. The traditional Mass had been one of the prominent casualties of the Second Vatican Council of the early 1960s, when Pope John XXIII liberalized the church’s practices, liturgy and relations with other denominations.

Benedict, who was often quoted rebuking more liberal theologians who argued that the reforms of the council were a rejection of the church’s previous practices, reinstituted many of the dormant symbols of the church’s power — he wore fur-lined vestments and jewel-laden rings, and he revived the papal tradition of wearing bright red leather shoes, symbolizing Jesus’ bloodied feet as he was sent to his crucifixion.

Such symbols were on par with the massive visual statement the church made through its majestic churches and cathedrals and its unequaled collection of great works of art, Benedict contended.

“All the great works of art, the cathedrals — the Gothic cathedrals and the splendid Baroque churches — are a luminous sign of God, and thus are truly a manifestation, an epiphany of God,” he said in 2008.

Benedict was 78 and already frail in 2005 when he became pope — the oldest pope elected in almost three centuries — and by Feb. 11, 2013, then 85, he had had enough.

“After having repeatedly examined my conscience before God, I have come to the certainty that my strengths due to an advanced age are no longer suited to an adequate exercise of the Petrine ministry,” he said at a Vatican meeting with his cardinals, referring to the Catholic doctrine of papal primacy. “Strength which in the last few months has deteriorated in me to the extent that I have had to recognize my incapacity to adequately fulfill the ministry entrusted to me.”

And with that, Benedict gave three weeks’ notice that he was stepping down at the end of the month.

Benedict took the title pope emeritus and continued to wear the papal white. But he returned the Ring of the Fisherman, which traditionally is ceremonially destroyed with a blow from a hammer after a pope dies. And he asked that he be addressed as Father Benedict.

The former pope also maintained a cordial relationship with Francis. Both men were beaming when they embraced Dec. 8, 2015, before opening the Holy Door at St. Peter’s Basilica to mark the start of the Catholic Holy Year, or Jubilee. In June 2016, Francis kissed Benedict on both cheeks to help celebrate the 65th anniversary of the former pope’s ordination.

Their relationship was fictionalized in the 2019 movie “The Two Popes,” an adaptation of Anthony McCarten’s play “The Pope.” The movie depicts Benedict summoning Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, the liberal archbishop of Buenos Aires, Argentina, who would become Pope Francis, to the Vatican in secret to disclose that he intended to resign.

Over a series of conversations, Benedict, played by Anthony Hopkins, confesses that he can no longer hear God’s words and his belief that perhaps Bergoglio should succeed him as the only man who might be able to shatter the Vatican bureaucracy and reform the institution.

Change is needed, Benedict says, but “change is compromising,” and he is incapable of compromising. “For my entire life, I have been alone, but never lonely, until now,” he says.

No comments:

Post a Comment