The timeless, futile effort to fix circadian rhythms with tech

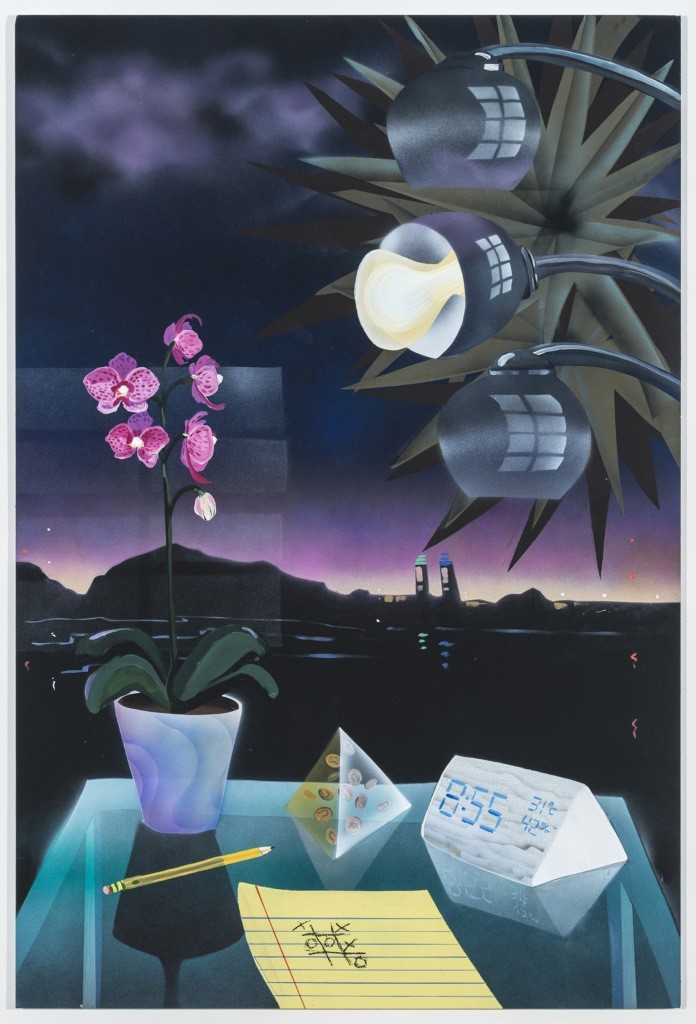

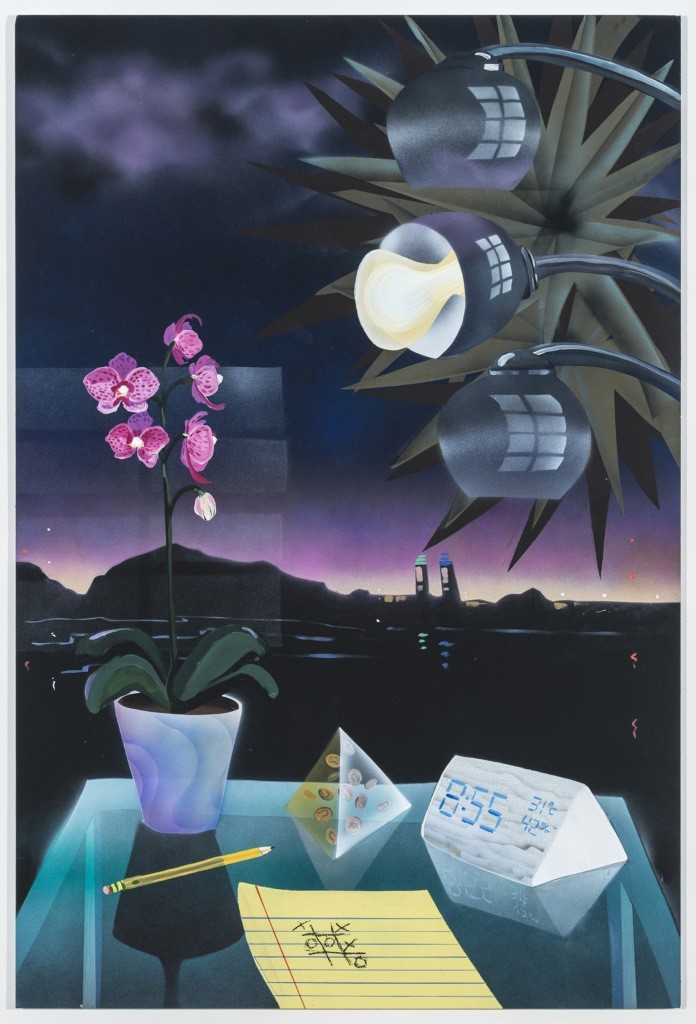

Image: Miami Nocturne (2018) by Melissa Brown. Courtesy the artist.

In 1998, as part of an ambitious marketing campaign for their line of “Beat” watches, Swatch proposed a total overhaul of the global timing system. It involved abolishing time zones and establishing a new meridian located at their headquarters in Biel, Switzerland, from which time would be measured not in 24 hours, but in 1,000 “beats” after midnight — each one equivalent to about a minute and 26.4 seconds. Among others, Nicholas Negroponte, founder and then-director of the MIT Lab, attended the launch. “Now is now and the same time for all people and places,” Negroponte was quoted on the Swatch Internet Time website. “Cyberspace has no seasons. The virtual world is absent of night and day. Internet Time is not driven by the sun’s position, it is driven by yours — your location in space and time.”

While this notion of the internet’s independence from organized time persists, the excitement surrounding it does not. Recent years have seen a wave of research lamenting the effects of internet usage on sleep patterns and eating habits. As the authors of A Very Short Introduction to Circadian Rhythms explain, we are living through a time of “Great Circadian Disruption,” in which sleeping patterns and bodily demands are increasingly divorced from natural stimuli. The reign of the clockface — and of the astronomical rhythms it approximates — has ostensibly ended, giving way to a soup of digital time in which timecodes persist as a way of organizing an endless flow of information, rather than referring us back to a world outside of the screen. Our relationship to the elusive flow of “natural time” is presumed to be in crisis, just like our relationship to the wider “natural world.”

The body is now presumed to have more in common with the segmented clock than with the “vapor” of internet time

“Natural time,” however, proves difficult to define: Is it the regimented rhythm of the clockface, or is it the movement of the moon and stars that governed social rhythms before it? Temporal ideals emerge as ghosts of what has been lost in the digital age, paving the way for a range of additional technologies — including SAD Lamps, blue-light filters, smart watches and time-specific social media such as BeReal — that promise to help users calibrate their rhythms with an imagined standard. In seeking an objective sense of time to structure our experiences of the internet, we ignore the fact that time is fundamentally relative. We need new ways of theorizing time in the digital age, which don’t presume the existence of a static, natural relationship to time, common to all.

When Christian Marclay’s beloved film The Clock came to the Tate Modern in 2019, I waited in line for two hours around 1 a.m. to get my glimpse of it. When I got in more than one person in the theater was snoring. I was also struggling to keep myself awake and I remember nearly nothing of what I saw, except for that I had a vague sense of witnessing something important; even if we’d missed the midnight hour (supposedly the film’s most exciting part) and even if we never made it to the 3 a.m. mark (a famed moment in a different way, when Marclay supposedly ran out of footage and resorted to compilations of footage of clocks going haywire). I do remember that sitting in the theater was inexplicably calming; like sitting inside a lullaby.

The Clock is a 24-hour supercut of shots of clocks and time-pieces from primarily Western films and television shows, collected painstakingly by a team of volunteer researchers. A large part of its widespread allure resides in the fact that it unfolds in “real time,” with the result that the activities of the characters onscreen supposedly reflect the engagements that the audience are missing in order to sit in the cinema theater. In some ways, The Clock provides an experience of immediacy or liveness, bringing fiction closer to reality and the past closer to the present. But as Stacey D’Erasmo writes for the New Yorker, in another sense it portrays clock time as a lost relic, something that now only belongs to fiction or to the past. On the internet, D’Erasmo writes, the contemporary day is “not a pie but a vapor, a tenuous notion” — in light of which the enormous popularity of the synchronized precision of Marclay’s work can be seen as a nostalgic reaction, “akin to the rise of the nature special as species were disappearing at a rapid rate from the planet.”

Writing in the 1970s, “chronogeographers” Don Parkes and Nigel Thrift argued that the experience of time was made up of the interplay of internal and external factors, and that harmonizing these factors was a key factor in wellbeing. They drew attention to the importance of “pacemakers” — events like the evening news, tied to clock time, that would synchronize rhythms on a local, city-wide, or even national scale. If the internet is largely seen as having dissolved the pacemakers that were embedded in “old media,” then Marclay’s work allows viewers to experience a sense of belonging to a shared rhythmicity that emerges not only between disparate films, but also between Marclay’s montage and the viewer. As Richard Martin summarizes: “the clips that appear just before the top of the hour are full of people rushing to appointments, excited about meeting someone or anxious about catching a train. The clips that appear just after the hour has struck are more melancholic and involve a certain slackening of time — moments of regret at missed opportunities or absent lovers.” The poetry of Marclay’s work comes from the organicism of these shifts and the fact that they seem to have been as unconscious for the filmmakers as they are for the fictional characters that populate the scenes.

The daily-task format of certain apps promises a limited sphere of intervention

Writing about Swatch Internet Time in the early ’90s, Negroponte emphasized the individuality of lived time within cyberspace as a source of freedom (“internet time is not driven by the sun’s position — it is driven by yours”). Today, it is precisely this sense of disconnection from rhythmic external stimuli that leads theorists like Jonathan Cary to lament the deadness of 24/7 time (internet time), which, he writes, is more aligned with the machine (“the inanimate, inert and unchanging”) than with the human body. The Clock advertises an ideal of shared time — a secret temporal logic which unites people even in the most spontaneous of actions. This shared time is neither distinctly social nor distinctly biological, because there is a sense that the two exist in harmony: Little rhythmic shifts seem to come from the body as much as they come from cultural norms.

But clock time was not always viewed as being this organic. The accusation that is today leveled against the internet — that it distorts natural rhythmicity and turns the human body into a machine — was once leveled against clock time itself. In 1944, Canadian writer George Woodcock wrote an essay entitled The Tyranny of the Clock in which he argued that “the clock turns time from a process of nature into a commodity that can be measured and bought and sold like soap or sultanas,” as a result of which “men actually became like clocks, acting with a repetitive regularity which had no resemblance to the rhythmic life of a natural being.” The body is now presumed to have more in common with the segmented clock face — which at least approximated natural rhythms, even if it locked them into a standard compatible with the needs of capital — than it does with the “vapor” of internet time.

A while ago, I saw a tweet where someone claimed to be able to tell what time zone someone was tweeting from without any other information: an early morning post (energetic, well-punctuated, logical) was different than a late-night post (impulsive, riddled with spelling errors, a bit horny). The tweet was a joke, but it hinted at a desire to relocate the body in the temporal flow of the online. In 2017, researchers from the University of Bristol analyzed over 800 million tweets from the UK over four years in order to determine whether the circadian rhythm’s influence on mood could be detected in social media patterns. By using machine learning to detect words associated with different emotions, the study found “strong, but different, circadian patterns for positive and negative moods.” The expression of anger online, in particular, was seen to mirror the known variations of plasma cortisol concentrations that make people more likely to be angry at certain times of day. What would happen if someone, following Marclay, attempted a supercut of the internet? Would there be similar revelries at midnight, 3 a.m. lull, periods of heightening excitement as the hour approaches and periods of reflection as it passes?

One of the primary anxieties of the digital age is that an online life is a kind of half-life; that time spent on the internet is wasted time rather than lived time. Temporality and rhythmicity is the most popular way to differentiate between the live and the inanimate, the natural and the artificial, even if it is not the most accurate: hence the alarm that a McDonalds burger doesn’t seem to go bad over a 10-year span. In moments when the internet feels truly timeless — when it begins to feel repetitive, predictable, and divorced from external shifts — it begins to feel dead. Researcher Ludmila Lupinacci, tracing the experience of “liveness” in social media (which she defines as “what feels animated, pulsating, injected with life”) notes that often the experience of using traditional social media — which involves “navigating aimlessly and pointlessly through an apparent unceasing waterfall of content” — is associated with impressions of deadness or lifelessness. We can step into the content waterfall at any point in the day, and it will still be there: endlessly, lifelessly flowing.

Reinjecting the internet with a sense of life involves attention to temporal variation

Reinjecting the internet with a sense of life involves attention to temporal variation, which is perhaps why newer platforms like BeReal aim to provide a more authentic antidote to other social media by intervening in the temporal structure of user communication. Like in Marclay’s The Clock, BeReal — in requiring that all its users post only once at an assigned, randomized point in the day — offers the experience of witnessing “real time” while simultaneously participating in it. In The Clock, I am balanced on the edge of sleep just as those onscreen are drifting off, united by the demands of the body. On BeReal, I make coffee at 3 p.m. and I post about it, while at the same one of the 10 or so friends I follow makes their own afternoon coffee. We react to one another’s posts.

Because the internet is seen to have contributed to the eradication of social “pacemakers” (the evening news, the close of the working day), something else has to provide the sense of an overarching “communal time” on the internet. Writing about BeReal, Rob Horning argues that, as in The Clock, “what is perceived as “real” … is the fact of social coordination itself rather than the particular contingencies of any individual’s contribution.” As Horning writes, BeReal can be seen as part of a wider trend of apps that center on a daily task. A recent example is Wordle; earlier ones include the app HQ Trivia, a daily live trivia game by the creators of Vine which was released in 2017, and Dispo, a photo-sharing app which replicated the experience of a disposable camera (photos would “develop” overnight and appear at 9 a.m. the following morning). The daily-task format promises a limited sphere of intervention, unlocking more “free time” away from the internet. This is misleading: in confining itself to a randomized two-minute window, apps like BeReal also extend their reach over the entire 24-hour cycle, creating a daily event which is preceded by anticipation, and succeeded by reflection (looking over other’s posts, watching the reactions roll in).

The pacemaker-style app attempts to bring an experience of communality back to the highly individuated temporal flow of the online experience, playing on nostalgia for an age when media had a more predictable temporal structure. This is never an explicit part of the branding. What emerges through BeReal is not a social rhythm so much as a kind of shared arrhythmia which professes to highlight the innate patterns of the day rather than intervening in them. BeReal separates itself from the “timeless” world of the internet by situating itself in the “real” flow of objective time. The app is in many ways a communal work of fiction: It tells us more about how we construct different points in the day — how we build pictures of the day’s “natural shifts” — than how people actually experience those shifts.

With time, as with space, the locus of the “natural” is constantly shifting. Caught between two fictions — the rigidity of clock time, and the undifferentiated soup of internet time — people hoping to rediscover a “healthy” or rewarding relationship to time increasingly turn to the purest, most natural, and most objective timepiece of all: the body clock. Fears around the internet’s disruption of time often revolve less around its interventions in the fabric of social life than around its bodily manipulations. The body’s relationship to time is often evoked as a lost source of synchronization, and therefore of community. This is why “blue light exposure” late at night has become such a social fixation, with a whole economy of technologies that promise to help us tune our screens to natural lighting shifts, rather than focusing on what exactly we are doing with the screen, or how that might influence our mood, alertness, or sense of rhythm. Even the recognition of “chronotypes” — different inherent attunements, such as the early-rising “lark” and the late-rising “owl” — creates the sense of different communities based around shared bodily conditions. Thrown out of sync by the demands of contemporary life, we apparently need to first tap into our own bodily needs in order to re-discover a temporality that we can share with the earth, and with others.

Chronobiology — a field of biology that examines the effects of cyclic processes on living organisms — tells us that our bodies possess an internal clock that is tuned (“entrained”) by certain environmental stimuli, known as “zeitgebers,” literally “time-givers” (light is the primary zeitgeber, which is why screen-light is thought of as a circadian disruptor). Chronobiologists Russell Foster and Leon Kreitzman estimate that in the average human body, across a 24-hour time span, there is a peak in libido from 6–8 a.m., or 10 p.m.–12 a.m.; a peak in logical reasoning from 10–12 a.m.; a peak in serotonin from 2–4 p.m.; a peak reaction time at 3:30 p.m.; and many other variations in body temperature, blood pressure, grip strength, melatonin release, bowel movements — though they note that testing whether these rhythms persist in controlled conditions is incredibly difficult.

Circadian science hasn’t been around all that long: its contemporary form dates back to around the 1950s, and its presence in popular culture is even more recent. The research around the impact of blue light on sleep patterns, which is the most widely cited example of how technology intervenes in the circadian rhythm, is in its infancy, and in culture its importance is generally overstated. It makes sense that the rise of popular interest in the circadian rhythm — as well as the popularity of its attendant technologies, such as the SAD Lamp, Night Modes and f.lux — would coincide with both the rise of digital culture, and with a heightened awareness of ecological breakdown. The idea that our bodies are innately responsive to environmental phenomena is a comforting reminder that humans are still innately “part of nature.” The desire to locate the circadian body-clock within the internet is a way of fumbling around for our “true selves,” and for a sense of belonging to a shared temporal rhythm.

We are haunted by the specter of an innate, perfect rhythm, the antidote to the endless lonely day of the internet

But what is the rhythmic life of a natural being? It has of course never been the case that “we all have the same 24 hours in the day.” People spend their time in different ways, and some people have more to spend than others. If an app like BeReal were reflecting a “real” picture of time, it would tell quite a different story, revealing the ways in which our time is intensely differentiated. “If standardized time was a fiction more or less driven by capitalism,” writes D’Erasmo, “it might be possible that [internet] atemporality is a fiction more or less driven by capitalism as well.”

In her book In the Meantime: Temporality and Cultural Politics, Sarah Sharma writes that while theorists spend a lot of time lamenting the end of “public sphere” in spatial terms, there has been little attention paid to what the public sphere might mean in temporal terms. She critiques the idea that time under capitalism is universally “speeding up,” instead paying attention to the ways in which time is made to work unevenly. Public time isn’t just an abstract synchronization, it is relational. Digitally-enabled 24/7 time means a very different thing for the person who orders an UberEats burger at 2 a.m. than it does for the person who delivers it. These two experiences of time are not individualized, but interdependent.

For Sharma, the discourse of speed that accompanies characterizations of contemporary non-stop 24-hour life only masks the ways that achieving “the perfect calibration” to an ideal temporality is an unattainable goal; and how “slowness” is a luxury that can necessarily only be enjoyed by some under capitalism. The idea that we are living in a “dangerously sped-up culture” only fuels the desire to outsource undesirable tasks (perceived as “non-time”) to others. Early conceptions of internet time tapped into the optimism and sense of freedom that surrounded the early internet, but they also conjured a vision of an intensely individualized relationship to time, in which one’s use of time had no consequences beyond one’s own individual timeline. “Internet Time is not driven by the sun’s position, it is driven by yours,” said Negroponte; it would be more accurate to say that the particular way time bends and warps and unfolds for each of us is based not primarily on the position of the sun, nor on an internal body clock, but instead on the living and non-living entities that we share time with.

Sharma argues that the contemporary relationship to time is characterized by “the looming expectation that everyone must become an entrepreneur of time control.” Each of us must “recalibrate” to temporal expectations that vary widely along lines of power and privilege.

Increasingly, technologies offer to assist in this recalibration. As Dylan Mulvin has argued, night modes and blue-light blocking filters individualize responsibility for exhaustion and fatigue. SAD Lamps encourage us to take control of internal rhythms in order to better comply with externally-imposed temporalities. Apps like SelfControl” and Apple’s Screen Time feature encourage us to manage the ratio of time spent online, while circadian apps like BeReal designate a correct moment to be in the internet, one which remains fundamentally unpredictable. These technologies play on the sense of being out of sync, isolated from a communal time, and suggest that each one of us is responsible for rediscovering the flow of natural time in which we will feel at home once more. The sense of temporal not-belonging is thus felt as a personal failure to manage one’s own time effectively. This is what makes an experience like The Clock so poignant to so many people today, and perhaps why I experienced the work as calming: temporal communality at last! Floating in the Great Flow of Time! Without effort!

In Zadie’s Smith’s short story “The Lazy River,” she evokes a donut-shaped swimming pool with an artificial current. “The Lazy River” is “a metaphor and at the same time a body of artificial water,” located in a holiday resort in Southern Spain dominated by British tourists. The lazy river enforces the “principle of universal flow,” but this flow is variously navigated. Some use elaborate flotation devices. Others try as hard as they can to swim against the current. Two young girls, glued to their phones, obsessively document their holiday, and they spend less time in the river than anyone else. “All life is in here, flowing. Flowing!” Smith writes — but as the story flows on, exceptions abound. All life here flowing, except for “the ladies who plait hair, one from Senegal and the other from the Gambia.” Except for the Tunisian twins, Rico and Rocco, hired to entertain the hotel guests in the evening. And except for the pool cleaners — a man with a long mop held in place by another man, “who grips him by the waist, so that the first man may angle his mop and position himself against the strong yet somniferous current and clean whatever scum we have left of ourselves off the sides.”

Sharma writes: “Capital invests in certain temporalities — that is, capital caters to the clock that meters the life and lifestyle of some of its workers and consumers. The others are left to recalibrate themselves to serve a dominant temporality.” Some float in the lazy river, and others clean it. Sharma advises that we learn to live with temporal awareness; to see the ways everything exists in time and is made of time. Most of all, she cautions that seeking to “reclaim” time stolen from us by the internet will never be an adequate response to the sense of being “time-poor” under capitalism, because the idea of “free time” is at its heart an individualistic solution, rather than a systemic one. In Sharma’s words: “living with a temporal awareness means recognizing how one’s management of time has the potential to further diminish the time of others.”

I don’t pretend to understand the theory of general relativity, but I understand what relativity means in a general sense. If spacetime is a fabric, as Einstein tells us, then the shortcomings of the idea of “free time” become obvious: pulling the duvet over to your side of the bed always leaves someone over the other side a little exposed. This idea of relativity is what is often left out of the narrative that the internet has broken our relationship to “natural time.” It is presumed that if we could synchronize a perfect harmony between inner and outer time, we would rediscover a sense of belonging to the planet and to each other. We are haunted by the specter of an innate, perfect rhythm; the antidote to the endless lonely day of the internet, lying just out of reach.

The internet is not a timeless zone, but it is not surprising that the experience of using the internet sometimes feels that way. It does produce the sense of being alienated from social time, but this is not because of anything inherent about the internet — its straddling of time-zones, or its dependence on light-emitting screens. Instead, that sense of alienation is a product of the fact that the internet as it is serves what Sharma has identified as a dominant temporal order: one that locks each person into their own individualized time-scale, making them feel fully responsible for their success or failure to adhere to the particular temporality that is assigned to them. Instead of searching for a natural time-structure, we can learn to think of our rhythmic or temporal lives as always simultaneously internal and external, and always connected to the rhythms of those around us, whether we are online or offline.

Lauren Collee is a London-based writer and PhD student. Her essays and short fiction have appeared in Another Gaze, Uneven Earth, Eyot Magazine and others.

Temporal Belonging

The timeless, futile effort to fix circadian rhythms with tech

Image: Miami Nocturne (2018) by Melissa Brown. Courtesy the artist.

In 1998, as part of an ambitious marketing campaign for their line of “Beat” watches, Swatch proposed a total overhaul of the global timing system. It involved abolishing time zones and establishing a new meridian located at their headquarters in Biel, Switzerland, from which time would be measured not in 24 hours, but in 1,000 “beats” after midnight — each one equivalent to about a minute and 26.4 seconds. Among others, Nicholas Negroponte, founder and then-director of the MIT Lab, attended the launch. “Now is now and the same time for all people and places,” Negroponte was quoted on the Swatch Internet Time website. “Cyberspace has no seasons. The virtual world is absent of night and day. Internet Time is not driven by the sun’s position, it is driven by yours — your location in space and time.”

While this notion of the internet’s independence from organized time persists, the excitement surrounding it does not. Recent years have seen a wave of research lamenting the effects of internet usage on sleep patterns and eating habits. As the authors of A Very Short Introduction to Circadian Rhythms explain, we are living through a time of “Great Circadian Disruption,” in which sleeping patterns and bodily demands are increasingly divorced from natural stimuli. The reign of the clockface — and of the astronomical rhythms it approximates — has ostensibly ended, giving way to a soup of digital time in which timecodes persist as a way of organizing an endless flow of information, rather than referring us back to a world outside of the screen. Our relationship to the elusive flow of “natural time” is presumed to be in crisis, just like our relationship to the wider “natural world.”

The body is now presumed to have more in common with the segmented clock than with the “vapor” of internet time

“Natural time,” however, proves difficult to define: Is it the regimented rhythm of the clockface, or is it the movement of the moon and stars that governed social rhythms before it? Temporal ideals emerge as ghosts of what has been lost in the digital age, paving the way for a range of additional technologies — including SAD Lamps, blue-light filters, smart watches and time-specific social media such as BeReal — that promise to help users calibrate their rhythms with an imagined standard. In seeking an objective sense of time to structure our experiences of the internet, we ignore the fact that time is fundamentally relative. We need new ways of theorizing time in the digital age, which don’t presume the existence of a static, natural relationship to time, common to all.

When Christian Marclay’s beloved film The Clock came to the Tate Modern in 2019, I waited in line for two hours around 1 a.m. to get my glimpse of it. When I got in more than one person in the theater was snoring. I was also struggling to keep myself awake and I remember nearly nothing of what I saw, except for that I had a vague sense of witnessing something important; even if we’d missed the midnight hour (supposedly the film’s most exciting part) and even if we never made it to the 3 a.m. mark (a famed moment in a different way, when Marclay supposedly ran out of footage and resorted to compilations of footage of clocks going haywire). I do remember that sitting in the theater was inexplicably calming; like sitting inside a lullaby.

The Clock is a 24-hour supercut of shots of clocks and time-pieces from primarily Western films and television shows, collected painstakingly by a team of volunteer researchers. A large part of its widespread allure resides in the fact that it unfolds in “real time,” with the result that the activities of the characters onscreen supposedly reflect the engagements that the audience are missing in order to sit in the cinema theater. In some ways, The Clock provides an experience of immediacy or liveness, bringing fiction closer to reality and the past closer to the present. But as Stacey D’Erasmo writes for the New Yorker, in another sense it portrays clock time as a lost relic, something that now only belongs to fiction or to the past. On the internet, D’Erasmo writes, the contemporary day is “not a pie but a vapor, a tenuous notion” — in light of which the enormous popularity of the synchronized precision of Marclay’s work can be seen as a nostalgic reaction, “akin to the rise of the nature special as species were disappearing at a rapid rate from the planet.”

Writing in the 1970s, “chronogeographers” Don Parkes and Nigel Thrift argued that the experience of time was made up of the interplay of internal and external factors, and that harmonizing these factors was a key factor in wellbeing. They drew attention to the importance of “pacemakers” — events like the evening news, tied to clock time, that would synchronize rhythms on a local, city-wide, or even national scale. If the internet is largely seen as having dissolved the pacemakers that were embedded in “old media,” then Marclay’s work allows viewers to experience a sense of belonging to a shared rhythmicity that emerges not only between disparate films, but also between Marclay’s montage and the viewer. As Richard Martin summarizes: “the clips that appear just before the top of the hour are full of people rushing to appointments, excited about meeting someone or anxious about catching a train. The clips that appear just after the hour has struck are more melancholic and involve a certain slackening of time — moments of regret at missed opportunities or absent lovers.” The poetry of Marclay’s work comes from the organicism of these shifts and the fact that they seem to have been as unconscious for the filmmakers as they are for the fictional characters that populate the scenes.

The daily-task format of certain apps promises a limited sphere of intervention

Writing about Swatch Internet Time in the early ’90s, Negroponte emphasized the individuality of lived time within cyberspace as a source of freedom (“internet time is not driven by the sun’s position — it is driven by yours”). Today, it is precisely this sense of disconnection from rhythmic external stimuli that leads theorists like Jonathan Cary to lament the deadness of 24/7 time (internet time), which, he writes, is more aligned with the machine (“the inanimate, inert and unchanging”) than with the human body. The Clock advertises an ideal of shared time — a secret temporal logic which unites people even in the most spontaneous of actions. This shared time is neither distinctly social nor distinctly biological, because there is a sense that the two exist in harmony: Little rhythmic shifts seem to come from the body as much as they come from cultural norms.

But clock time was not always viewed as being this organic. The accusation that is today leveled against the internet — that it distorts natural rhythmicity and turns the human body into a machine — was once leveled against clock time itself. In 1944, Canadian writer George Woodcock wrote an essay entitled The Tyranny of the Clock in which he argued that “the clock turns time from a process of nature into a commodity that can be measured and bought and sold like soap or sultanas,” as a result of which “men actually became like clocks, acting with a repetitive regularity which had no resemblance to the rhythmic life of a natural being.” The body is now presumed to have more in common with the segmented clock face — which at least approximated natural rhythms, even if it locked them into a standard compatible with the needs of capital — than it does with the “vapor” of internet time.

A while ago, I saw a tweet where someone claimed to be able to tell what time zone someone was tweeting from without any other information: an early morning post (energetic, well-punctuated, logical) was different than a late-night post (impulsive, riddled with spelling errors, a bit horny). The tweet was a joke, but it hinted at a desire to relocate the body in the temporal flow of the online. In 2017, researchers from the University of Bristol analyzed over 800 million tweets from the UK over four years in order to determine whether the circadian rhythm’s influence on mood could be detected in social media patterns. By using machine learning to detect words associated with different emotions, the study found “strong, but different, circadian patterns for positive and negative moods.” The expression of anger online, in particular, was seen to mirror the known variations of plasma cortisol concentrations that make people more likely to be angry at certain times of day. What would happen if someone, following Marclay, attempted a supercut of the internet? Would there be similar revelries at midnight, 3 a.m. lull, periods of heightening excitement as the hour approaches and periods of reflection as it passes?

One of the primary anxieties of the digital age is that an online life is a kind of half-life; that time spent on the internet is wasted time rather than lived time. Temporality and rhythmicity is the most popular way to differentiate between the live and the inanimate, the natural and the artificial, even if it is not the most accurate: hence the alarm that a McDonalds burger doesn’t seem to go bad over a 10-year span. In moments when the internet feels truly timeless — when it begins to feel repetitive, predictable, and divorced from external shifts — it begins to feel dead. Researcher Ludmila Lupinacci, tracing the experience of “liveness” in social media (which she defines as “what feels animated, pulsating, injected with life”) notes that often the experience of using traditional social media — which involves “navigating aimlessly and pointlessly through an apparent unceasing waterfall of content” — is associated with impressions of deadness or lifelessness. We can step into the content waterfall at any point in the day, and it will still be there: endlessly, lifelessly flowing.

Reinjecting the internet with a sense of life involves attention to temporal variation

Reinjecting the internet with a sense of life involves attention to temporal variation, which is perhaps why newer platforms like BeReal aim to provide a more authentic antidote to other social media by intervening in the temporal structure of user communication. Like in Marclay’s The Clock, BeReal — in requiring that all its users post only once at an assigned, randomized point in the day — offers the experience of witnessing “real time” while simultaneously participating in it. In The Clock, I am balanced on the edge of sleep just as those onscreen are drifting off, united by the demands of the body. On BeReal, I make coffee at 3 p.m. and I post about it, while at the same one of the 10 or so friends I follow makes their own afternoon coffee. We react to one another’s posts.

Because the internet is seen to have contributed to the eradication of social “pacemakers” (the evening news, the close of the working day), something else has to provide the sense of an overarching “communal time” on the internet. Writing about BeReal, Rob Horning argues that, as in The Clock, “what is perceived as “real” … is the fact of social coordination itself rather than the particular contingencies of any individual’s contribution.” As Horning writes, BeReal can be seen as part of a wider trend of apps that center on a daily task. A recent example is Wordle; earlier ones include the app HQ Trivia, a daily live trivia game by the creators of Vine which was released in 2017, and Dispo, a photo-sharing app which replicated the experience of a disposable camera (photos would “develop” overnight and appear at 9 a.m. the following morning). The daily-task format promises a limited sphere of intervention, unlocking more “free time” away from the internet. This is misleading: in confining itself to a randomized two-minute window, apps like BeReal also extend their reach over the entire 24-hour cycle, creating a daily event which is preceded by anticipation, and succeeded by reflection (looking over other’s posts, watching the reactions roll in).

The pacemaker-style app attempts to bring an experience of communality back to the highly individuated temporal flow of the online experience, playing on nostalgia for an age when media had a more predictable temporal structure. This is never an explicit part of the branding. What emerges through BeReal is not a social rhythm so much as a kind of shared arrhythmia which professes to highlight the innate patterns of the day rather than intervening in them. BeReal separates itself from the “timeless” world of the internet by situating itself in the “real” flow of objective time. The app is in many ways a communal work of fiction: It tells us more about how we construct different points in the day — how we build pictures of the day’s “natural shifts” — than how people actually experience those shifts.

With time, as with space, the locus of the “natural” is constantly shifting. Caught between two fictions — the rigidity of clock time, and the undifferentiated soup of internet time — people hoping to rediscover a “healthy” or rewarding relationship to time increasingly turn to the purest, most natural, and most objective timepiece of all: the body clock. Fears around the internet’s disruption of time often revolve less around its interventions in the fabric of social life than around its bodily manipulations. The body’s relationship to time is often evoked as a lost source of synchronization, and therefore of community. This is why “blue light exposure” late at night has become such a social fixation, with a whole economy of technologies that promise to help us tune our screens to natural lighting shifts, rather than focusing on what exactly we are doing with the screen, or how that might influence our mood, alertness, or sense of rhythm. Even the recognition of “chronotypes” — different inherent attunements, such as the early-rising “lark” and the late-rising “owl” — creates the sense of different communities based around shared bodily conditions. Thrown out of sync by the demands of contemporary life, we apparently need to first tap into our own bodily needs in order to re-discover a temporality that we can share with the earth, and with others.

Chronobiology — a field of biology that examines the effects of cyclic processes on living organisms — tells us that our bodies possess an internal clock that is tuned (“entrained”) by certain environmental stimuli, known as “zeitgebers,” literally “time-givers” (light is the primary zeitgeber, which is why screen-light is thought of as a circadian disruptor). Chronobiologists Russell Foster and Leon Kreitzman estimate that in the average human body, across a 24-hour time span, there is a peak in libido from 6–8 a.m., or 10 p.m.–12 a.m.; a peak in logical reasoning from 10–12 a.m.; a peak in serotonin from 2–4 p.m.; a peak reaction time at 3:30 p.m.; and many other variations in body temperature, blood pressure, grip strength, melatonin release, bowel movements — though they note that testing whether these rhythms persist in controlled conditions is incredibly difficult.

Circadian science hasn’t been around all that long: its contemporary form dates back to around the 1950s, and its presence in popular culture is even more recent. The research around the impact of blue light on sleep patterns, which is the most widely cited example of how technology intervenes in the circadian rhythm, is in its infancy, and in culture its importance is generally overstated. It makes sense that the rise of popular interest in the circadian rhythm — as well as the popularity of its attendant technologies, such as the SAD Lamp, Night Modes and f.lux — would coincide with both the rise of digital culture, and with a heightened awareness of ecological breakdown. The idea that our bodies are innately responsive to environmental phenomena is a comforting reminder that humans are still innately “part of nature.” The desire to locate the circadian body-clock within the internet is a way of fumbling around for our “true selves,” and for a sense of belonging to a shared temporal rhythm.

We are haunted by the specter of an innate, perfect rhythm, the antidote to the endless lonely day of the internet

But what is the rhythmic life of a natural being? It has of course never been the case that “we all have the same 24 hours in the day.” People spend their time in different ways, and some people have more to spend than others. If an app like BeReal were reflecting a “real” picture of time, it would tell quite a different story, revealing the ways in which our time is intensely differentiated. “If standardized time was a fiction more or less driven by capitalism,” writes D’Erasmo, “it might be possible that [internet] atemporality is a fiction more or less driven by capitalism as well.”

In her book In the Meantime: Temporality and Cultural Politics, Sarah Sharma writes that while theorists spend a lot of time lamenting the end of “public sphere” in spatial terms, there has been little attention paid to what the public sphere might mean in temporal terms. She critiques the idea that time under capitalism is universally “speeding up,” instead paying attention to the ways in which time is made to work unevenly. Public time isn’t just an abstract synchronization, it is relational. Digitally-enabled 24/7 time means a very different thing for the person who orders an UberEats burger at 2 a.m. than it does for the person who delivers it. These two experiences of time are not individualized, but interdependent.

For Sharma, the discourse of speed that accompanies characterizations of contemporary non-stop 24-hour life only masks the ways that achieving “the perfect calibration” to an ideal temporality is an unattainable goal; and how “slowness” is a luxury that can necessarily only be enjoyed by some under capitalism. The idea that we are living in a “dangerously sped-up culture” only fuels the desire to outsource undesirable tasks (perceived as “non-time”) to others. Early conceptions of internet time tapped into the optimism and sense of freedom that surrounded the early internet, but they also conjured a vision of an intensely individualized relationship to time, in which one’s use of time had no consequences beyond one’s own individual timeline. “Internet Time is not driven by the sun’s position, it is driven by yours,” said Negroponte; it would be more accurate to say that the particular way time bends and warps and unfolds for each of us is based not primarily on the position of the sun, nor on an internal body clock, but instead on the living and non-living entities that we share time with.

Sharma argues that the contemporary relationship to time is characterized by “the looming expectation that everyone must become an entrepreneur of time control.” Each of us must “recalibrate” to temporal expectations that vary widely along lines of power and privilege.

Increasingly, technologies offer to assist in this recalibration. As Dylan Mulvin has argued, night modes and blue-light blocking filters individualize responsibility for exhaustion and fatigue. SAD Lamps encourage us to take control of internal rhythms in order to better comply with externally-imposed temporalities. Apps like SelfControl” and Apple’s Screen Time feature encourage us to manage the ratio of time spent online, while circadian apps like BeReal designate a correct moment to be in the internet, one which remains fundamentally unpredictable. These technologies play on the sense of being out of sync, isolated from a communal time, and suggest that each one of us is responsible for rediscovering the flow of natural time in which we will feel at home once more. The sense of temporal not-belonging is thus felt as a personal failure to manage one’s own time effectively. This is what makes an experience like The Clock so poignant to so many people today, and perhaps why I experienced the work as calming: temporal communality at last! Floating in the Great Flow of Time! Without effort!

In Zadie’s Smith’s short story “The Lazy River,” she evokes a donut-shaped swimming pool with an artificial current. “The Lazy River” is “a metaphor and at the same time a body of artificial water,” located in a holiday resort in Southern Spain dominated by British tourists. The lazy river enforces the “principle of universal flow,” but this flow is variously navigated. Some use elaborate flotation devices. Others try as hard as they can to swim against the current. Two young girls, glued to their phones, obsessively document their holiday, and they spend less time in the river than anyone else. “All life is in here, flowing. Flowing!” Smith writes — but as the story flows on, exceptions abound. All life here flowing, except for “the ladies who plait hair, one from Senegal and the other from the Gambia.” Except for the Tunisian twins, Rico and Rocco, hired to entertain the hotel guests in the evening. And except for the pool cleaners — a man with a long mop held in place by another man, “who grips him by the waist, so that the first man may angle his mop and position himself against the strong yet somniferous current and clean whatever scum we have left of ourselves off the sides.”

Sharma writes: “Capital invests in certain temporalities — that is, capital caters to the clock that meters the life and lifestyle of some of its workers and consumers. The others are left to recalibrate themselves to serve a dominant temporality.” Some float in the lazy river, and others clean it. Sharma advises that we learn to live with temporal awareness; to see the ways everything exists in time and is made of time. Most of all, she cautions that seeking to “reclaim” time stolen from us by the internet will never be an adequate response to the sense of being “time-poor” under capitalism, because the idea of “free time” is at its heart an individualistic solution, rather than a systemic one. In Sharma’s words: “living with a temporal awareness means recognizing how one’s management of time has the potential to further diminish the time of others.”

I don’t pretend to understand the theory of general relativity, but I understand what relativity means in a general sense. If spacetime is a fabric, as Einstein tells us, then the shortcomings of the idea of “free time” become obvious: pulling the duvet over to your side of the bed always leaves someone over the other side a little exposed. This idea of relativity is what is often left out of the narrative that the internet has broken our relationship to “natural time.” It is presumed that if we could synchronize a perfect harmony between inner and outer time, we would rediscover a sense of belonging to the planet and to each other. We are haunted by the specter of an innate, perfect rhythm; the antidote to the endless lonely day of the internet, lying just out of reach.

The internet is not a timeless zone, but it is not surprising that the experience of using the internet sometimes feels that way. It does produce the sense of being alienated from social time, but this is not because of anything inherent about the internet — its straddling of time-zones, or its dependence on light-emitting screens. Instead, that sense of alienation is a product of the fact that the internet as it is serves what Sharma has identified as a dominant temporal order: one that locks each person into their own individualized time-scale, making them feel fully responsible for their success or failure to adhere to the particular temporality that is assigned to them. Instead of searching for a natural time-structure, we can learn to think of our rhythmic or temporal lives as always simultaneously internal and external, and always connected to the rhythms of those around us, whether we are online or offline.

Lauren Collee is a London-based writer and PhD student. Her essays and short fiction have appeared in Another Gaze, Uneven Earth, Eyot Magazine and others.

No comments:

Post a Comment