Is present in your nightmares, in your pull towards despair

And the sickness of the culture, and the sickness in our hearts

Is a sickness that’s inflicted by this distance that we share

– Kae Tempest, Tunnel Vision (from Let Them Eat Chaos, 2016)

Archbishop Thabo Makgoba was giving the Holy Communion. As he nodded to each supplicant it struck me how the Eucharist, this ancient Christian ritual, requires that each week priests have to look into people’s eyes. By doing so they must acknowledge someone else’s existence at a deeper level.

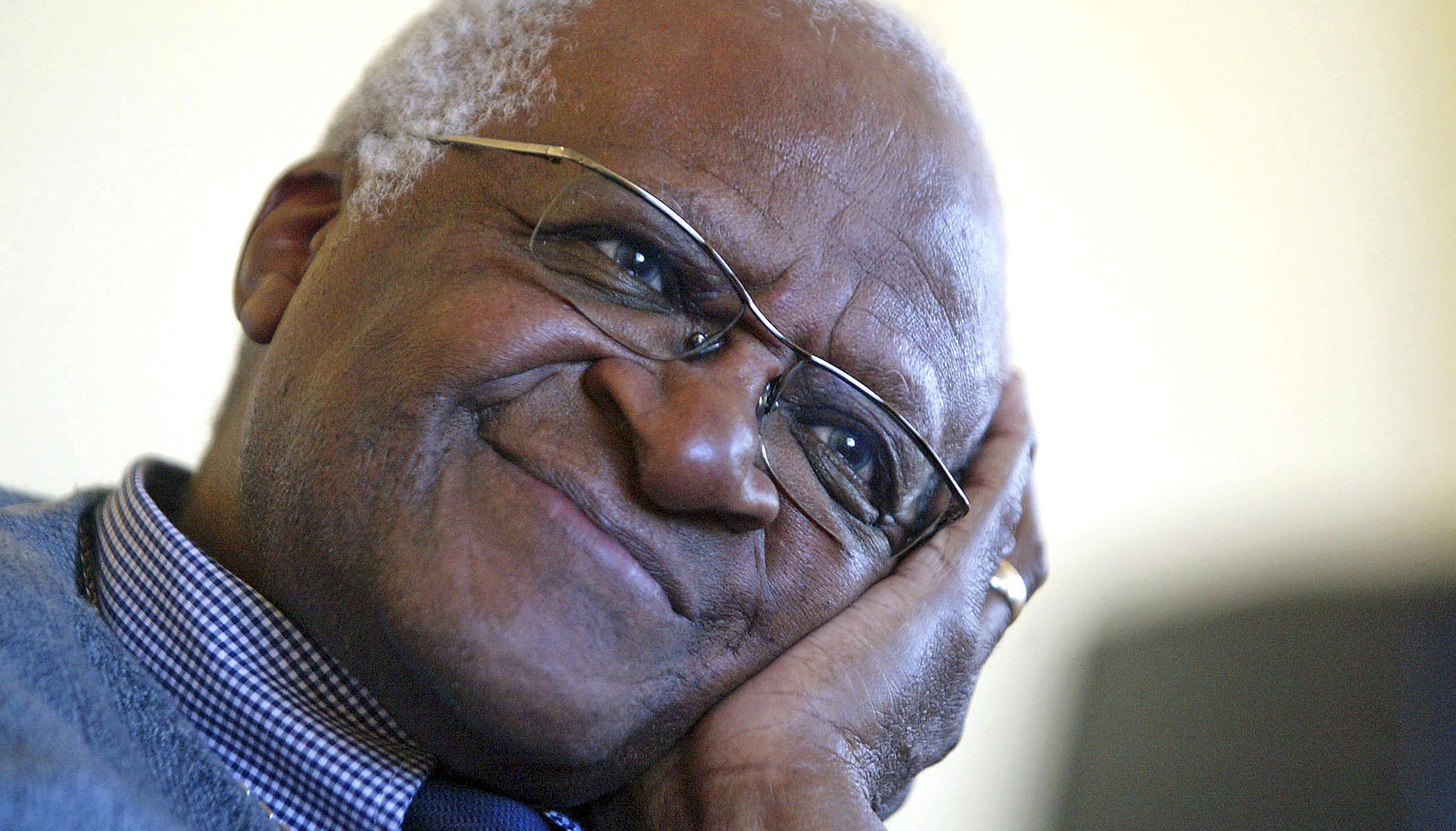

I thought this must have been one of the reasons Desmond Tutu always remained grounded in humanity and passionate about social justice throughout his life; because, as a priest, he always had to look into people’s faces.

When you look in someone’s eyes a connection between strangers is established and with that connection must come an unsolicited accountability; for a priest it’s a weekly revelation of the humanity you share with other people, a chance to see into their agony, ecstasy and for the most part just their common-or-garden, everyday humanity.

If and when you look in other people’s eyes you can’t escape other people’s being.

Of course, as with everything, throughout history there have been many priests who can and do cut the ties between their witness and the lives of their congregants, but Desmond Tutu wasn’t that type of priest. He emerged from a generation of religious leaders who took their commandments as much from people’s eyes as from their biblical texts.

This was at the heart of the dispute the South African Council of Churches (SACC) had with the Dutch Reformed Church back in the day.

I don’t do Holy Communion and I’m not a Christian, but this epiphany reawakened my own awareness of the power of connection you feel with people you don’t know that comes through simple greetings – simply seeing them. This is something my friend Claire Keeton has also written about recently.

I often go out to run or ride my bike early in the morning. On the street, the hour or two as light gathers on either side of dawn is always special.

People without private transport amble or hurry to work.

It’s a time before the day has ground people down, the rush taken over; the point when we stop being and are simply doing.

On dawn-time journeys through city streets and parks I observe homeless people, domestic workers, recyclers, shop owners.

I greet every person I meet.

Very few people fail to lift their eyes, pull a small smile, say a few words. Making eye contact with a stranger is like shaking hands with your eyes. It elicits a small smile, a few words, a fleeting sense of connection with a stranger that warms you both.

Connection is important and, just as with Desmond Tutu, it brings accountability and solidarity (or it should).

As I try to process the feelings that connection unleashes, the best place to turn to is poetry because poetry, like the morning, undresses the excuses and rationales we make for our poverty of empathy and solidarity with the people around us, never mind those far away.

“That person on the street that you walk past without looking at,

Or the face on the street that walks past you without

looking back

…

Look again, allow yourself to see them.”

Rummaging through the streets and people of modern London, Tempest happens upon themes and feelings that belong in any city of the world; whatever the geography, human behaviour is pretty much the same.

Tempest writes about ordinary people with unacknowledged stories, “half way between non-existent and infinite”, gangsters and vandals (“inside they’re delicate, but outside they’re reckless” … “in the old days they would have been warriors”/ but in these days they’re out on the high street smoking, nothing to fight for but fighting itself”), and I recognise the brand-new ancients in the people I greet.

Finally, something else Tutu saw in people’s faces – and which I feel every time I connect with a stranger – is the ghost of hope. Against all odds hope keeps us alive in a world that is increasingly broken and despairing. Freed from the machines, freed from people’s expectations and demands, freed from your own whip of depression and despair, there is still a beauty that sits at the heart of our being.

In Let Them Eat Chaos (2016) Tempest writes;

Can’t sleep, can’t wake, sitting in our boxes

Notching up our victories as other people’s losses

Justice, justice, recompense, humility

Trust is, trust is something we will never see

Till love is unconditional

The myth of the individual has left us disconnected, lost, and pitiful

We’re working every dread day that is given us

Feeling like the person people meet

Really isn’t us

Like we’re going to buckle underneath the trouble

Like any minute now

The struggle’s going to finish us

And then we smile at all our friends

…

Even when I’m weak and I’m breaking

I’ll stand weeping at the train station

‘Cause I can see your faces

It’s strange, but not unexpected, how quickly people have moved on from the lesson according to the life of Desmond Tutu. But we do so at the cost of our humanity. If the only thing we did was to look once more into other people’s faces and acknowledge our oneness, accept responsibilities that arise from it, we might be capable of paying a more fitting tribute to Tutu’s life and legacy. DM/MC/ML

Kae Tempest’s recent books of poetry are available on Spotify. In 2020 her play Paradise, a reimagining of Sophocles’s play Philoctetes, was performed at the UK’s National Theatre. Their latest album of poetry, The Line is a Curve, is due to be published in April 2021.

No comments:

Post a Comment