WARREN, Ohio — There’s an old saw in boxing that the last thing to go is power. Footwork fades, it gets harder to bob and weave, but if you can still punch—and take punches—you’ve still got a career.

So it is with Don King. Last week, he returned to the cold and snow of the Northeast Ohio of his youth, promoting a slate of fights in Warren, an hour’s drive from his hometown of Cleveland.

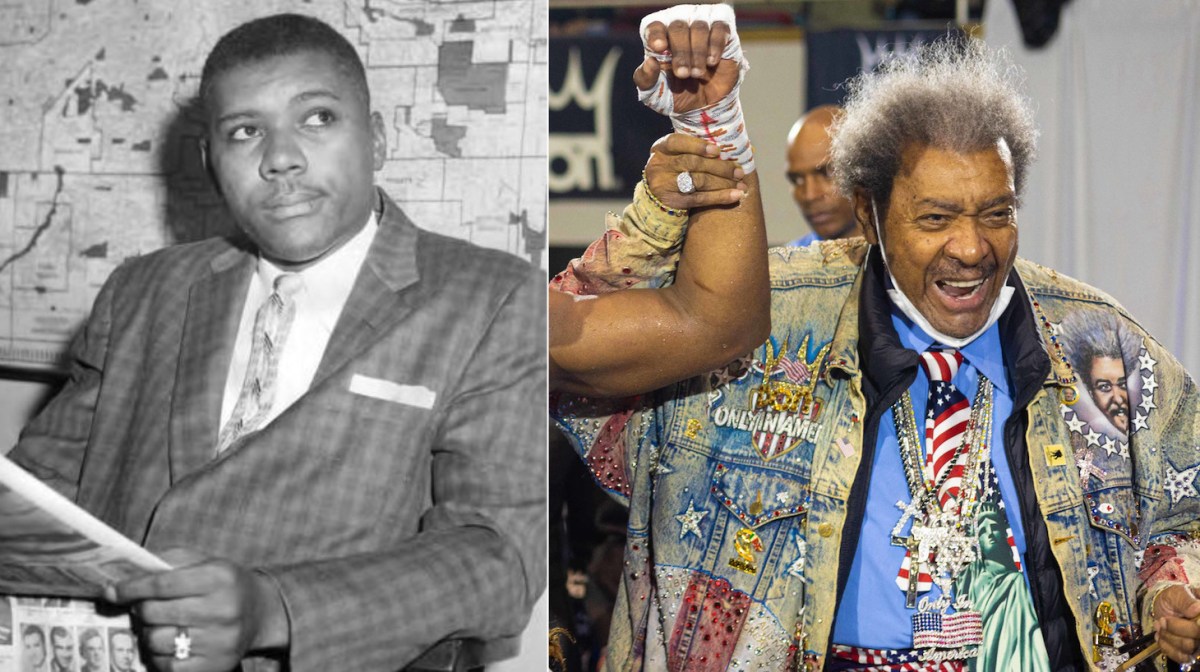

On Wednesday, four days before the fights, he shuffled into a ballroom at a posh, freshly restored hotel outside of Warren for the introductory news conference. He was late enough to make his entrance a grand one, and though he remains an imposing figure with broad shoulders, they stooped as he made his way to the podium. He’s 90 years old, after all.

Once he got there and the lights went on, he was electric. It was the same mile-a-minute patter he’d become famous for back when boxing was a staple of HBO’s Saturday night programming, on various local talk shows and in interviews with his hometown papers, where he was presented as a success story of a black man who’d lived the street life but had made something of himself.

He recited the beginning of the Declaration of Independence. He talked about how there ain’t no mountain high, ain’t no valley low, ain’t no river wide enough to keep this slate of fights from happening. He even dabbled in a little verse.

“Hey everybody, let’s have some fun. Live it once, and when you’re dead, you’re done. No matter whether you are young or old, let the good times roll.”

Even as a young man, King was famous around here. But when his name regularly appeared in Cleveland’s newspapers it wasn’t for sports promotion. Instead it was for his role in the city’s large and well-established organized crime scene. He was, sometimes by turns and often all at once, a numbers runner and bookie and loan shark and enforcer. He fell into boxing promotion only after a stint in prison for killing a man, and remains one of the best-known names in an increasingly marginalized sport.

And he’s still beloved here, where, as Northeast Ohio wilted under the hammer of deindustrialization in the 1980s, King ceaselessly demanded respect for his hometown, advocating for a downtown arena where he could hold events, touting Cleveland as the comeback city.

Last week in Trumbull County, people lined up to speak well of him. King was recognized with a proclamation by the city of Maple Heights, and Warren Mayor Doug Franklin attended the news conference to read his own proclamation, marking Jan. 26 as Don King Day in Warren, noting that he lives, breathes and believes his self-mythologizing catchphrase, “Only in America.”

Warren’s about 60 miles away from the East Side of Cleveland, but it seems light years away from where King spent his early years, as what the Call And Post—Cleveland’s African-American weekly newspaper, now owned by King—once called “just about the most important man in the rackets right now.”

“I am a cat with nine lives,” King said at a virtual news conference before the fight, describing the path that led him back home.

It’s hard to convey just how widespread and entrenched organized crime was in mid-century American cities in the Northeast and Midwest. Many cities were ports, and docks were often controlled by organized crime through union operations. Nightclubs were usually the domain of the mob as well, either through ownership or supplying related services, like laundry, trash collection, or coin-operated machines. “Circulation wars” between newspapers wasn’t just hyperbole; newspapers recruited toughs to hold corners for single-copy sales.

But the most lucrative stream of revenue was usually gambling, and Cleveland was rife. In nearby rural hinterlands, clubs were set up to offer card and dice games, as well as entertainment. (In fact, one particularly enterprising set of crooks established their own municipality near Warren for purposes of getting a liquor license for an illegal gambling hall. That step also made them virtually untouchable by local or county law enforcement.)

And then there was “the number.” Thousands of dollars came in daily on illegal lotteries, usually based on some three-digit combination in the day’s news, like stock market figures or racing wagers. It was a particularly popular pastime in poorer ethnic neighborhoods, where you could get in on the action for pennies.

It was in this world, on the East Side, that a young Donald King operated. The East Side was the older part of town, and after World War II, many white people with the economic wherewithal moved to the city’s West Side (where land development was one of the many interests of Mickey McBride, a mob-adjacent businessman who’d served as circulation director for the Cleveland News and is best known for being the original owner of the Cleveland Browns), or to one of the suburbs then sprouting outside the city limits.

King was one of the “Big Five” operators of numbers clearinghouses in Cleveland. Legend has it that his success in those early years was attributable to his memorization and computation skills, allowing him to ply his trade without the paper trail that undid so many competitors. In 1954, men tried to rob one of his numbers houses. He exchanged gunfire with one of them, Hilary Brown, who was fatally wounded. The killing was ruled justifiable.

He also ran a nightclub, where he met R&B singer Lloyd Price, who was one of the first singers—of any color—to realize the value of owning your own catalog and distributing your own records. Price would play a key role in King’s rise.

King was also acquainted with Shondor Birns, a notorious gangster who was just as flamboyant as the young numbers runner. King paid protection to Birns, putatively a restaurateur, but his lengthy criminal career had started as one of McBride’s street toughs hawking the Cleveland News. (Birns would go on to be played by Christopher Walken in 2011’s Kill the Irishman, a movie about the 1970s mob war in Cleveland.)

Ultimately, King stopped paying protection to Birns. Shortly after that, his house was bombed.

The crime would ultimately lead to one of the major Supreme Court cases of the era. A search for suspects led police to the home of Dollree Mapp (the initial tip to police was “widely believed” to come from King himself), who wouldn’t let officers in. Officers returned waving what they claimed was a warrant. They entered and didn’t find the suspect, but did find pornography, for which Mapp was prosecuted and convicted. She appealed, and ultimately, the Supreme Court ruled in 1961 in Mapp v. Ohio that no search warrant was produced or accounted for, and exclusionary protection—the idea that evidence illegally obtained could not be used at trial—extended to state courts. (Previously, it had just been in use in federal cases.) Mapp has been referred to as the Rosa Parks of the Fourth Amendment.

Four months after the bombing, a gunman lying in wait shot King with a shotgun as he walked out to his car. He then testified against Birns—in what ultimately resulted in a mistrial—earning the nickname “The Talker” for his rapid-fire testimony.

In 1967, King was convicted of second-degree murder for the beating death of Sam Garrett a year earlier over a $600 gambling debt, and faced a potential life sentence in prison. But his sentence was initially suspended, and five months after the verdict, Judge Hugh Corrigan suddenly reduced the conviction to manslaughter. In his biography Only In America: The Life And Crimes Of Don King, journalist Jack Newfield alleged that Corrigan was under the sway of organized crime.

Even with a reduced sentence, King was headed to prison. “I was sent to serve time,” he said last week. “I made the time serve me.” He self-educated at Marion Correctional Institution, and when he was paroled after four years, he returned to Cleveland, where Forest City Hospital was foundering. The hospital was known as the city’s “colored hospital,” not only serving the area’s black population, but providing opportunities for African-Americans in the healthcare field.

King, who’d met Muhammad Ali before through Price, impressed on the singer to help him sell the boxer on an exhibition at the old Cleveland Arena. Ali fought several exhibitions against local fighters, and in the end, the gate totaled more than $85,000—$15,000 of which went to the hospital. King reportedly took home $30,000.

Local newspaper accounts suggested concerns that King was using the exhibition to raise a stake to get back into organized crime. Instead, he went into boxing promotion. “I started at the top and never left,” he said Saturday night.

You more or less know the story from there. King promoted fights in Las Vegas, New York, and Atlantic City, where he made friends with an upstart Queens guy who owned one of the casinos; you might have heard of him. King backed that Queens guy’s successful presidential bid in 2016, noting that he wasn’t a politician. Of course, both were skilled promoters with, uh, unique hair, who weren’t shy about deploying hyperbole.

King, a self-described “Republocrat,” has politics that defy pigeonholing. He supported Donald Trump—and George W. Bush in 2000—but also Barack Obama. He isn’t shy about encouraging vaccination against COVID-19 and mask-wearing, saying, “It’s better to have the vaccine and masks and not need them, than to need them and not have them.”

(A Call And Post columnist, Grover Crayton, suggested in 1981—perhaps tongue in cheek—that King himself should run for president. “Remember, the current occupant of the White House was a two-bit movie actor, before he became a ‘public relations gimmick’ for big business,” Crayton wrote. He wasn’t wrong.)

He also promoted fights in Northeast Ohio, where even to this day he can use his own fame to sell tickets. One of those fights was Ali against Chuck Wepner at the old Richfield Coliseum, the fight that inspired Sylvester Stallone to write Rocky.

By the 1980s, when he returned to Cleveland for a series of bouts, he’d achieved the respectability he’d long sought. King was pardoned for his manslaughter conviction by Gov. Jim Rhodes shortly before he left office in 1983. Rhodes said, “Don King has paid his debt to society and earned this pardon through his role in civic affairs.” Letters of support for the pardon came from corners as varied as Cleveland Mayor George Voinovich, Jesse Jackson, Browns owner Art Modell, Indians executive Gabe Paul, and Coretta Scott King.

The site of Saturday night’s fights in Warren was Packard Music Hall, named for William D. Packard, who with his brother James formed an electric company, later part of General Motors, and then an eponymous car company—out of spite. James Packard was dissatisfied with a Winton he bought in Cleveland, and was effectively told, “If you can build a better car, do it.” So he did. That’s one way to get famous around here.

Today, the hall is mostly used for concerts, but Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini, the Youngstown native who was ringside to call the fights for TV, said he’d fought there several times on his way up to the lightweight championship in the early 1980s.

The crowd was a hot one. The parking lot was packed well before the card started, and by the featured event, few empty seats could be seen in the hall, which has a capacity around 2,500. Northeast Ohio has always loved its fights, and more than that, its fighters, and many who aren’t even from the area have taken the region to their hearts as well. Earnie Shavers trained in Calcutta, not far from Pennsylvania and the West Virginia panhandle. Elyria became Leon Spinks’s second home. Mike Tyson bought a mansion in Southington, just outside Warren. (One draw was that he could keep his tigers there; Ohio has lax laws regulating wild animals.) King himself set up a base of operations in Ashtabula County, with a home in Windsor, and a training camp not far from there, in Orwell.

Saturday’s fights were all sanctioned by the North American Boxing Association, affiliated with the WBA, one of the alphabet soup of boxing’s largest sanctioning bodies. It wasn’t a major card by any means, though it’s hard to say that many fights these days are “major.” Four of the six went the distance, including the two feature events. In a cruiserweight title fight, Ilunga Makabu beat Thabiso Mchunu in a split decision, and Trevor Bryan remaining undefeated, beating Jonathan Guidry—a late add to the card—in a heavyweight title match, also a split decision.

Southpaw Johnnie Langston earned the NABA cruiserweight belt by beating Nick Kisner with a five-round TKO, and Tre’Sean Wiggins took the vacant welterweight title by scoring a third-round TKO over Cody Wilson. And in the walkout bout (an undercard fight deliberately held back in case the rest of them end early, and put on after the main event—i.e. when most of the crowd is already walking out), Michael Moore of Cleveland scored a unanimous decision.

“Make sure you tell people you saw six great fights,” King said afterward. “We put on a great show, even better than I prognosticated.”

One of King’s early successes was the “Rumble in the Jungle,” the heavyweight fight between Ali and George Foreman in Kinshasa, Zaire. Makabu is from that country, now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Saturday night must have seemed just like the good old days to King, as fans unfurled a Congolese flag and yelled, in an echo of that long-ago Kinshasa crowd, “Makabu bomaye! Makabu bomaye!” (Makabu, kill him! Makabu, kill him!)

After the fight, someone raised the prospect of a fight in the Congo. Makabu was excited about the idea. Even at age 90, so was King.

“I will slow down when I go to heaven,” he said.

Vince Guerrieri is an award-winning journalist and author in the Cleveland area. He likes Lake Erie perch sandwiches, Jim Traficant and long walks on the field at League Park. His website is vinceguerrieri.com, and you can follow him on Twitter @vinceguerrieri.

No comments:

Post a Comment