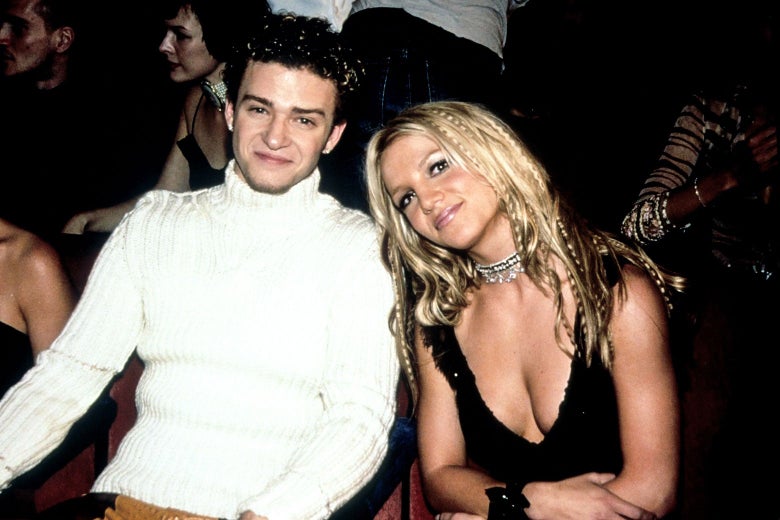

On Sept. 23, 2002, a newly single, 21-year-old Justin Timberlake sat down for a radio interview. It wasn’t routine: He was set to appear on The Star & Buc Wild Morning Show, on the most influential hip-hop station in the country, Hot 97. At the time, hosts Star and Buc Wild were the ultimate tastemakers. Their radio show was famous for irreverently grilling celebrities like A Tribe Called Quest, Busta Rhymes, and Nas. They’d established a wide fan base for their fearless, blunt interviewing style. Timberlake, meanwhile, had recently split from both his boy band, *NSYNC, and his girlfriend, Britney Spears. A week before, he’d debuted his solo single “Like I Love You,” featuring Clipse. His chaste public persona was in the midst of a major revision.

Timberlake paused for a brief moment, letting out an awkward laugh. “Oh man.” His inflection shifted, and he exclaimed, “OK, I did it!”

“Justin Timberlake Admits Oral Sex With Spears,” read one headline. “Justin’s Low Blow May Send Britney Over the Edge,” read another.

A decade later, Star still remembers how that interview played out behind the scenes. “There were about five people in that room with us,” he told me recently, “and two of those people were representatives from Jive Records”—both Timberlake’s and Spears’ record label at the time. “The other three, I think, were part of Justin Timberlake’s management team.” Back then, Hot 97 wasn’t too enthusiastic about playing Timberlake’s music, despite the soloist’s attempts to self-brand as an “R&B” singer instead of a pop star. But Star liked him. “I said, ‘Hey man, I’m not trying to squeeze you and I’m not trying to be disrespectful, but you know, you and Britney just broke up,’ ” he explained. “He didn’t really want to talk about it, but I was like, ‘Look, I’ll play this goddamn song of yours, I swear to you, two times a day for two weeks if you could just give me some information here.’ ” Timberlake “kind of smiled, he almost turned beet red,” Star said. “I said, ‘Hey man, I’ll play it four times a day.’ Then I said, ‘Goddamn it, I’ll play this record five times a day, Justin, what do you think?’ ” They were just joking around, Star said. Then Justin gave him a quote to shock the tabloid world.

Publicly, 2002 Timberlake was the sensitive ex–boy bander, a heartbroken heartthrob too genteel to speak ill of his ex but savvy enough to burn her in his songs (without naming her, of course). Simultaneously, there were rumors that he privately said things like “Dude, smell my fingers” to choreographers to brag about having sex with America’s impossible sweetheart: objectified and infantile, the bang-able vestal virgin next door. When Justin admitted to having sex with Britney, it was a significant blow to Spears’ brand; at the time, she had told the press she wanted to try to remain celibate until marriage. But only recently has Timberlake’s reputation been affected by the way he acted and spoke back then, due in no small part to the popularity of the New York Times film Framing Britney Spears.

The conversation is likely to continue: The Times is releasing a new documentary on Friday, this time focused on Timberlake’s infamous Super Bowl incident with Janet Jackson. It’s a searing reminder of the part he played in the performance, its fallout, and the media’s continued scrutiny of female artists whose sexuality was inextricable from their image. Twenty years later, in a drastically changed cultural landscape, 2000s-era Justin Timberlake looks a lot different.

Between Britney and Janet, Justin once skated through controversies that had grievous PR effects on the women around him. Fortified by his undeniable musical talent—and make no mistake, he is one of the greatest performers of recent history—Timberlake’s boy-next-door identity endured for decades, even in the face of evidence that contradicted it. The new reckoning around him feels like a cultural exorcism, a chance to use the boy band vessel to purge ourselves of the evils he now represents to many. But behind the scenes, he was at once a canny self-marketer and a blank, withholding presence at the hub of conflict, surrounded by publicists and media and managers who were crafting his image, too. Timberlake has become the perfect emblem of a bygone era that rewarded guys exactly like him—until it didn’t.

Justin Timberlake was once the center of the universe, if you can remember far back enough: At the turn of the millennium, when fear of an unknown future could be pacified by the sugary-sweet five-part harmonies of Y2K boy bands, Timberlake was it. The pinnacle. *NSYNC’s rising star. An all-American, good-ol’ mama’s boy with a warm lyric tenor from Shelby Forest, Tennessee, Timberlake was blessed with a symmetrical face and thick curls hoisted to the gods and given the appearance of ramen.

He was born in 1981. His stepfather, Paul Harless, was a Baptist church choir director, and his mother, Lynn Harless, was soon to become one of the greatest stage parents in American pop music history. (Justin’s biological father, Randy Timberlake, whom Lynn referred to as the “sperm donor” in a 2006 Rolling Stone cover story, played bass and sang high harmonies in a bluegrass band. She credits him for her son’s virtuosity.) By 12, Timberlake was selected to star in Disney’s All-New Mickey Mouse Club. For two seasons, he was a star. At 13, the show was canceled, and the following year, *NSYNC’s Chris Kirkpatrick called Timberlake’s mom about a new vocal group. With a co-sign from the Disney Channel, *NSYNC became massive: 2000’s No Strings Attached sold more than 1.1 million copies in its first day and more than 2.4 million in its first week, setting a world record they held for 15 years. And Justin was their leader.

He was also a child when he entered the entertainment industry, and he was exploited by it: by manager Lou Pearlman, who had him and the other boys sign what litigator Helene Freeman labeled “the worst contract in music history,” according to fellow band member Lance Bass’ memoir, earning pennies on the dollar for the laborious hours worked. In 2006, Timberlake told Rolling Stone he felt the band “was being monetarily raped by a Svengali.” The next year, a landmark Vanity Fair article alleged that Pearlman had been far more than financially exploitative; he had sexually assaulted multiple boys whose careers he made. (Unlike the other members of *NSYNC, like Lance Bass, who released a documentary on Pearlman’s financial exploits in 2019, The Boy Band Con: The Lou Pearlman Story, Justin Timberlake has rarely spoken about the manager.)

It is also key to remember that as a product of the child-star system, Justin most likely grew up with media training in adolescence that meant internalizing publicity strategies intended to help him maintain relevance—such as staying quiet and listening to the professionals. Silence meant that his remarkable talent could speak for itself. It also meant that his public persona would come across as totally neutral, available to everyone.

John Norris, a former MTV VJ, remembers that his earliest interviews with Timberlake were during the 1999 *NSYNC tour, where Britney Spears was an opening act. Compared with the “frat boy” vibes of some of the other band members, Timberlake seemed less goofy, more self-aware. At one point, Timberlake took Norris for a drive in his new car. Hanging from his rearview mirror were the letters “WWJD.” “I’m such a heathen and know so little about being a good Christian boy that I knew nothing about the expression, ‘What would Jesus do,’ ” Norris recalled. “So, I was like, ‘What is that thing hanging there?’ And Justin downplayed it, ‘Oh, it’s just a thing for, like, checking yourself.’ And I’m like, ‘What do you mean? Does it stand for something?’ He didn’t want to go into it.” JT had the foresight not to make an explicitly religious statement; from a young age, he was “pretty resolutely anti-political,” said Norris, and “singularly uninterested in getting too divisive.” (Timberlake’s representatives did not respond to multiple requests for comment.)

In the early 2000s, this was what the culture demanded of mega pop stars. Apolitical rhetoric that, more often than not, veered conservative, the kind of post-9/11 patriotism that pretended not to take a side. Think Jessica Simpson, Christina Aguilera, and the next generation of Disney Channel starlets like Hilary Duff. If and when controversy arose—like in 2003, when Madonna and Spears shared a kiss at MTV’s Video Music Awards, with a camera trained on Timberlake in the audience—it was more often than not artfully staged. It was curated controversy, obsequious to the audience, orchestrated without requiring that stars take a particular ideological stand. (Consider the alternative: When Natalie Maines of the Dixie Chicks told a crowd in London that her group was “ashamed the president of the United States is from Texas” in advance of the U.S. invasion of Iraq, the group was blacklisted from radio, kneecapping the Dixie Chicks’ careers. People organized CD burnings in protest.)

During that era, the relationship between celebrities, paparazzi, and tabloid media was also particularly symbiotic and toxic. The supermarket magazine industry—not yet fully pummeled by the internet (TMZ, Just Jared, and PerezHilton.com didn’t appear until the mid-2000s)—was brutally competitive. Magazines like Us Weekly and People and Star were obsessed with obtaining exclusives, which required constant negotiation with celebrities and their publicists. And stars, in turn, were also dependent on tabloids to shape their own narratives.

After *NSYNC called it quits in 2002—largely because JT wanted to pursue a Michael Jackson–esque career—he released “Like I Love You,” from his then-forthcoming album Justified, recorded with the Neptunes and Timbaland, the very same track Star promised to blast multiple times a day on Hot 97. Today, many have argued that JT rose to solo fame on the shoulders of Black talent without fully giving them their due. Janet Jackson was featured on a late album cut, “(And She Said) Take Me Now,” just a few years before the infamous Super Bowl.

“Like I Love You” hit No. 11 on the Billboard Hot 100, an impressive benchmark for any performer, but not enough of a splash for him as a soloist, considering the total ubiquity of his group. It also arrived with a new, carefully cultivated image: Justin Timberlake was now the inoffensive everyman with some bite, done wrong by his perfidious ex-girlfriend.

It stands to reason that JT’s team recognized his breakup with Britney Spears made for some incredible publicity. If he couldn’t crack the Top 10 on his own, perhaps the narrative of America’s favorite power couple calling it quits, with JT as the tender-guy victim, would do the trick. According to tabloid sources from that era, Timberlake on his own was not a huge draw for readers. “He’s a pretty closed book. We always had trouble generating a lot of interest, and the interest was always in relation to whoever he was dating,” one former celebrity magazine editor from the 2000s told Slate. But the Britney breakup was a rare moment when Timberlake and his people played ball with the press. “I think we had five minutes with him and a photographer that he knew.” The tabloid editor recalled that they’d heard “Britney was sleeping with dancers or something like that,” but suggested “that was clearly his people getting in front of that story and being proactive.” (Rumors of infidelity have never been confirmed, though they continue to crop up.)

“The whole thing was a post-breakup cooperative,” he continued. “And we were telling the story that Britney cheated on him. That was the whole setup.” Given the imminent release of Timberlake’s new heartbreak album, the tabloid editor believed that “it was all very choreographed to be a revenge story.”

That new album was anchored by Justin’s first solo hit, “Cry Me a River”—a not-so-thinly-veiled critique of Britney, starring a video-actor lookalike. (“You don’t have to say what you did/ I already know, I found out from him,” he sang. “You told me you love me/ Why did you leave me all alone?”)

It cemented his identity as a deep-feeling solo artist. His sound recalled a white neo-soul Usher, indebted heavily to the Neptunes and Timbaland’s production, and his ethos was sexy, single, suit and tie–toting bachelor. He claims he wrote “Cry Me a River” in two hours. The messaging worked: Celebrity media tended to side with “Team Justin,” with headlines like “solo in every way, the sexy singer sets the record straight.” (There might be no better representation of the twisted cultural mores of the time than a 2002 Details cover line: “Can we ever forgive Justin Timberlake for all that sissy music? Hey … at least he got into Britney’s pants.”) Meanwhile, Britney headlines trumpeted: “Did she betray him?”, “Britney cracks up!”, and “Boozing Britney out of control.” As a result, her own interviews became damage control: No, she doesn’t do drugs. She likes red wine but never drinks in excess. She’s still the same girl we always knew her to be.

What frequently goes unmentioned about Justin’s relationship with ’00s tabloid culture is that he wasn’t actually very cooperative with the magazines that supported him. “Justin really despised paparazzi. Didn’t care about them one bit,” said Danny Ramos, a former paparazzo. “I couldn’t go up to him like, ‘Hey Justin, how you doing?’ He’s probably going to have me in a headlock.

“You get Justin Timberlake and a paparazzi together, and it’s explosion,” Ramos said. “It’s not going to go down good.”

If it sounds aggressive, that’s because it was. There are videos of Justin in the mid-2000s, particularly around the time he dated actor Cameron Diaz (aka, a year after he broke things off with Britney), where he is seen smacking paparazzi cameras out of the hands of videographers. These are violent, protective gestures that would’ve made memorable front-page news if it were Britney doing the attack—and of course, they did—like when she struck Ramos’ truck with an umbrella.

“There are a lot of celebrities”—“like Paris, or Lindsay, or Britney,” Ramos said—“I call it ‘teasing.’ One minute they want it, the next minute they don’t. And so, with Justin, it wasn’t like that at all. Justin was like, ‘Get that shit away from me.’ ” It was inherently gendered—Britney, Paris, and Lindsay were unable to change their minds about paparazzi; Justin was respected for his indignation. And that says nothing about the pressure they must’ve felt, as young women, to play nice with the camera men who knew where they lived and followed them daily.

Ramos, for his part, has started reckoning with this dynamic now in a way he says he didn’t back then. “It [was] a double standard,” he told me. “At that time, you could say it was like male chauvinism. It was, look, ‘Let’s just pick on the girls.’ It was like being bullied. And the guys were not picked on as much as the females.”

The mainstream media jumped on the breakup narrative Timberlake’s team was pushing, too. In an infamous interview with Barbara Walters on ABC News’ 20/20 conducted in 2002, Justin offered a cryptic but kind explanation for his breakup with Britney: “We’re not perfect. I don’t judge anybody.” Then he performed an unreleased track. “Frankly, baby, you ain’t worth the gas in my BMW,” he sang. “But to look at it positively/ At least you gave me another song about a horrible woman/ And that’s you.” Once again, he was a man scorned; Britney was unfaithful and cruel. When Walters asked Justin if he and Britney kept her pledge to wait to have sex until marriage, he laughed and said, “Sure.” Walters responded with a chuckle, “All right. I asked it, you answered, right? We both did our job.” (“I’ve only slept with one person my whole life, two years into my relationship with Justin. I thought he was the one. But I was wrong. I didn’t think he was gonna go on Barbara Walters and sell me out,” Britney told W magazine in 2003. “The most painful thing I’ve ever experienced was that breakup.”)

Britney wasn’t the only one who suffered the repercussions of JT’s media publicity. When Timberlake grabbed Janet Jackson’s chest at the 2004 Super Bowl halftime show—a stunt that was supposed to reveal red fabric and accidentally revealed her breast instead—he was able to return to the limelight unscathed. Immediately following the performance, Justin told Access Hollywood, “Hey, man, we love giving y’all something to talk about.” A week later, Janet was barred from the Grammys, and her career has never fully recovered. Justin, meanwhile, performed and won the award for Best Male Pop Vocal Performance. Even recently, as the Times announced it will turn its attention to this incident in its documentary, headlines referred to it as the “Janet Jackson Super Bowl Scandal.”

Over the next few years, his star continued rising. In 2006, on his solo record following the Super Bowl, FutureSex/LoveSounds, Timberlake essentially rewrote “Cry Me a River” in “What Goes Around … Comes Around.” (“If he hasn’t yet invented a persona intriguing enough to live up to his music, give him credit for being one of the few white men still brave enough to make Black music,” wrote one critic. “These songs update the early-eighties Minneapolis sound: tense drum machines, high-pitched synth squiggles, and staccato funk bass lines.” Beneath the sarcasm of that review, Justin was celebrated for good songs developed out of an infatuation with Black music.) The songs were masterfully crafted, a lesson in how to grow up post–teen pop superstardom. Their message was also a kind of self-victimization disguised as heartbreak. (“All of these things people told me/ Keep messing with my head/ Should’ve picked honesty/ Then you may not have blown it,” he sang in “Cry Me a River.”) The same could be said about his A-list acting roles that followed—Sean Parker in 2010’s The Social Network, Dylan Harper in 2011’s Friends With Benefits, hell, his beloved Saturday Night Live sketch, “Dick in a Box”—allowed Justin to have it both ways: act caddish and do an act sending up what it is to be a cad.

It wasn’t until nearly a decade later, with 2018’s critically panned Man of the Woods, that Timberlake’s golden boy status began to fade. JT’s 2013 neo-soul albums, The 20/20 Experience and The 20/20 Experience–2 of 2, were acclaimed for their consistency—glossy pop by a sensitive and sexy bon vivant. When he reappeared a few years later after a musical hiatus, gone were the Armani suits; instead, 2018 Justin played with folk music iconography, writing his own gospel without any eccentric elasticity, like a man in repentance. He seemed much more self-reflective in his art, and vague—the aging American icon leaning into Americana, attempting to come across as the matured family man instead of the flashy, heartbroken-yet-suave bachelor he had been for so many years. Publicly, it looked a lot like a retreat into whiteness—Western, Manifest Destiny–inflected sounds that celebrated the mythical masculinity of the great outdoors, flannel shirts and all, despite the fact that JT continued to work with producers Timbaland and the Neptunes on the project. The R&B was turned down, and so was the fun.

By 2018, cultural appropriation had permeated mainstream discourse. From an outside perspective, Man of the Woods seemed designed in part to signal understanding of the current moment. But the album was a disappointment. Justin was known for extravagant pop records and larger-than-life stadium shows, so when he stripped it back, he lost mainstream acclaim. (Loyal listeners, at least, were endeared to his back-home familism. JT’s son’s name, Silas, means “man of the woods” in Latin.) On one of the record’s better cuts, “Say Something,” with Chris Stapleton, they sing on the bridge, “Sometimes the greatest way to say something is to say nothing at all.” Part of Justin’s charm was always his blitheness, but on record, now, it lacked charisma.

In the years that followed, Justin Timberlake’s pop-star persona floundered. Media coverage shifted from glowing reviews to takedowns of his self-indulgent records. The cultural world around him evolved, too. In 2018, he signed up to work on Woody Allen’s film Wonder Wheel, telling the Hollywood Reporter he chose “not to get into” Allen’s pedophilia allegations. That same year, when cultural conversation was dominated by the #MeToo movement, Justin Timberlake wore a Time’s Up pin to the 2018 Golden Globes, despite working with Allen. He shared a selfie wearing the pin, smiling with his wife, Jessica Biel, and then captioned it—really—“DAMN, my wife is hot! #TIMESUP.”

In 2019, a paparazzo captured him holding hands with co-star Alisha Wainwright from the movie Palmer during a night out, and miscellaneous cheating rumors continued to swirl around him. So he issued a ham-fisted statement that was addressed to his “wife and family” but clearly meant as public damage control, apologizing for putting them through “an embarrassing situation” while insisting that he hadn’t cheated with his co-star. Then came 2021 and Framing Britney Spears. In the film, Timberlake’s interview with Diane Sawyer was put on full display, inspiring new online fervor against him. And so this time he issued a broad apology to all the women he’d—wittingly or unwittingly—hurt. “I have not been perfect in navigating all of this throughout my career,” he wrote on Instagram. He said that he’d “benefited from a system that condones misogyny and racism, and wrote, “I know this apology is a first step and doesn’t absolve the past.”

Timberlake had clearly come to a realization: His formerly marketable silence no longer flies. But his apologies felt to many like a belated, hollow attempt to take a stand after decades of studious neutrality. “I think that the pop zeitgeist, what we want from pop in 2021, or what real pop fans want from male pop artists is so different from what Justin Timberlake was: unassailably male, unassailably straight,” said Norris, the former MTV VJ. “I think there are qualities we celebrate now that were not even possible for a male pop artist in the early 2000s.” It was not “part of Justin’s makeup. I mean, he golfs, for fuck’s sake. Right? That’s it in a nutshell. Does Harry Styles golf? I don’t think so.” (He does, but the point stands.) Today, Timberlake writes songs for children (“Can’t Stop the Feeling!”), voices cartoons (Trolls), and stars in under-the-radar roles that validate his perennial soft-guy identity (Palmer).

But his lapse from the role of cultural darling is hardly a professional demise. Timberlake was simply given an opportunity that Britney Spears and Janet Jackson never got: to ease gently out of the spotlight, to step into the background but not to suffer because of it. He never faced the same harassment from paparazzi or the press that the women around him did, and his career has never really stalled. He performed at Joe Biden’s inauguration ceremony in January and has also been back in the studio—writing the flaccid feel-good song “Better Days” with singer-songwriter Ant Clemons. Hell, Trolls World Tour broke digital box office records and made $100 million in rentals alone last year. In January, Timberlake appeared on his good friend Jimmy Fallon’s Tonight Show, teasing new music. Since then, he’s been lying low amid comeback album rumors, waiting patiently, it seems, for his opportunity to reemerge. After all, Timberlake is a trained chameleon—ready to shapeshift to suit what he thinks the public wants.

No comments:

Post a Comment