Political cartooning is a dying profession, but there are more cartoons with politics than ever

IN 2007, AT THE AGE OF TWENTY-FOUR, I went to the Mayflower Hotel, in Washington, DC, to attend the fiftieth annual gathering of the Association of American Editorial Cartoonists. It was my first time there; I’d been invited as part of a cohort of about ten young people, an outreach by old-timers to the next generation. Newspapers were declining, and the AAEC was interested in how our profession could make money on the internet. A panel posed the question, “What is the future of editorial cartoons?”

At the time, the answer was me. I’d been cartooning professionally for four years, and I’d recently signed a syndication deal with United Media—home of Garfield and Nancy—that made me the youngest syndicated cartoonist in the country. I had nearly full-time employment drawing three editorial cartoons a week, and I filled every other waking hour with freelance illustration and work on a graphic novel. Roaming through the convention, feeling awkward in a borrowed blazer amid the chandeliers and Pulitzer winners, I felt that perhaps I had chosen something of a real profession—one that could garner respect, or enough of a living that I could toast myself and my colleagues in a ballroom once a year.

Later, I would come to see that convention and its open bar as a last hurrah. The event was a financial disaster for the AAEC, leaving it mired in debt. Over the next decade-plus, the organization’s venues became smaller and humbler, and the number of attendees dwindled and aged. I watched my peers move into other careers like graphic design and animation, which came with higher and steadier paychecks. Meanwhile, my promising start in syndication never paid me more than twenty thousand dollars a year. It turned out I wasn’t the future of editorial cartoons; I was one of the last people making a go at it.

Cartoonists often blame editors for their lack of interest and visual illiteracy—“words people,” we call them.

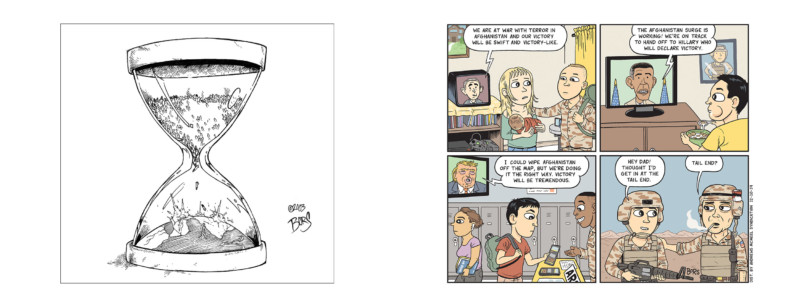

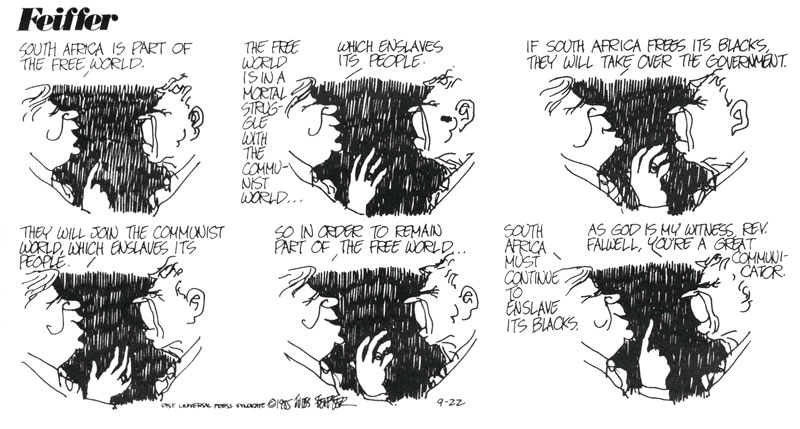

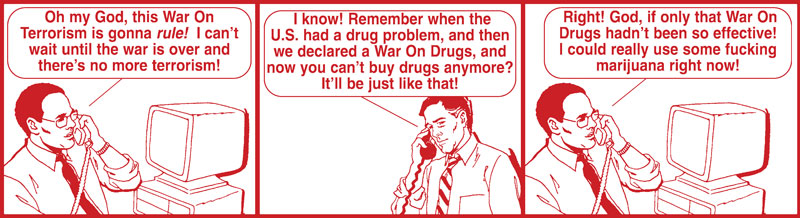

Matt Bors In a 2003 comic for syndication (left), I worried that the global war on terror would become a “forever war.” My prediction was correct; sixteen years later, I found myself drawing a version of the same cartoon for The Nib (below). Left: Courtesy Matt Bors, 2003; right: The Nib, 2019

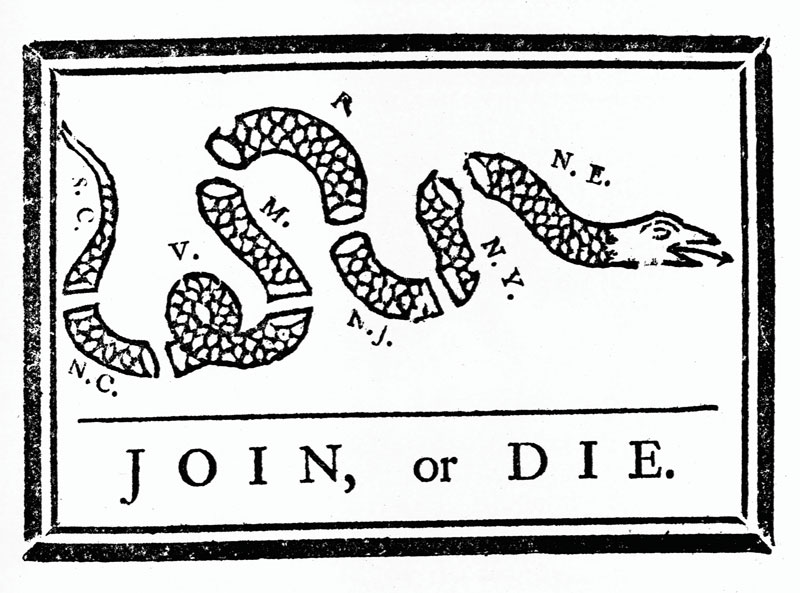

Ask a political cartoonist when the profession began, and you’re likely to hear that it all started with cave drawings—an answer that casts us as a fundamental part of society. In fact, Benjamin Franklin is credited with one of the first official political cartoons—“Join, or Die,” a commentary on the disunity of the colonies—in 1754 for his newspaper the Pennsylvania Gazette. In Great Britain, around the same time, William Hogarth, an artist and social critic, drew satirical illustrations. But the field didn’t coalesce into something with a name until 1841, with the arrival of a British humor magazine, Punch, which would soon coin the term “cartoon.”

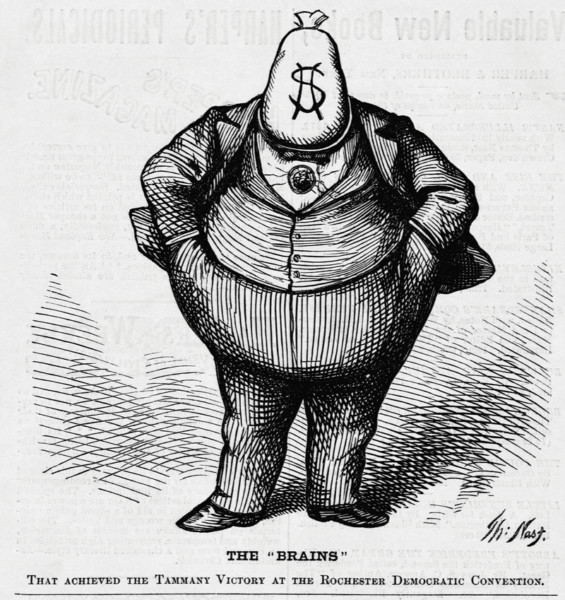

Political cartoons took off in popularity in tandem with the explosion in newspaper publishing facilitated by mass printing technology; illustrations were a convenient means to break up text-heavy pages. The godfather of the field, Thomas Nast, popularized such figures as the Democratic donkey and Uncle Sam. Cartooning in the second half of the nineteenth century for Harper’s Weekly, Nast devised intricate ink drawings that were painstakingly etched into engraving plates by assistants; his claim to fame was helping usher in the downfall of William “Boss” Tweed, a corrupt New York City politician convicted of stealing millions of dollars. Those were the glory years, when printed matter ruled the cultural conversation and political cartoons often appeared on newspapers’ front pages.

Benjamin Franklin This cartoon, first published in 1754 in the Pennsylvania Gazette, accompanied an editorial in which Franklin called for the American colonies to band together for protection against Native Americans and the French. Library of Congress / Corbis / VCG via Getty Images

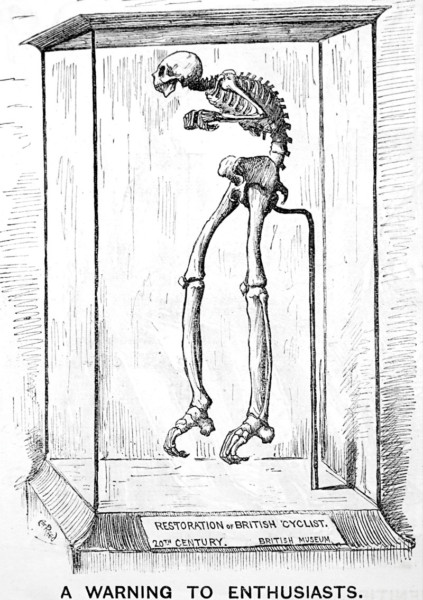

Punch An 1889 cartoon in Punch, a satirical magazine, warns cyclists about the penny-farthing. © CORBIS / Corbis via Getty Images

According to the Herb Block Foundation—a nonprofit established in 2001 by the bequest of Block, who had been a Washington Post cartoonist—by the start of the twentieth century there were an estimated two thousand editorial cartoonists employed by American newspapers. With the advent of radio, television, and other media, newspapers began a long, slow decline—and with them went the cartoonists. In 1957, the year the AAEC was formed, the association counted two hundred seventy-five staff cartoonists. Today, fewer than thirty political cartoonists are employed full-time, and every year the survivors are winnowed further by buyouts, layoffs, and age. In 2020, Pulitzer Prize winners Signe Wilkinson and Tom Toles retired from the Philadelphia Daily News and Washington Post, respectively; their jobs were not filled.

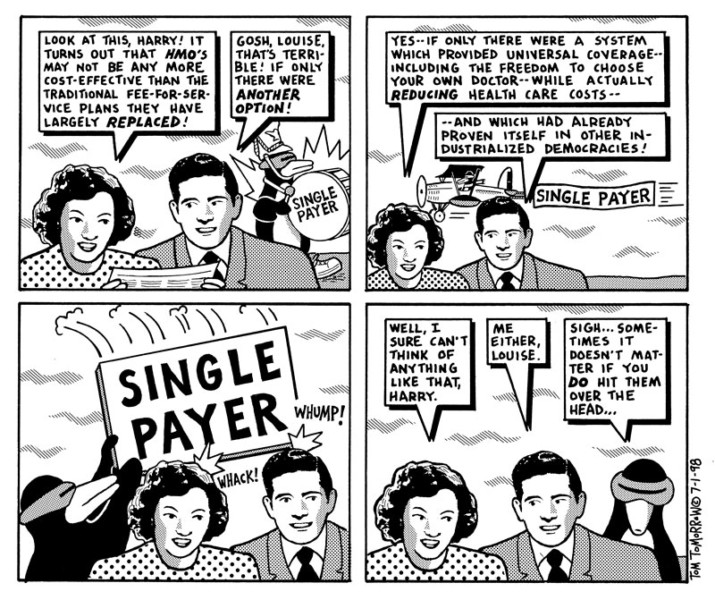

Even as the cartooning profession faded, the art of political cartooning grew sharper. Starting in the seventies, cartoonists experimented with new styles and modes of storytelling in the alt-weekly press. Jules Feiffer’s comics in the Village Voice, for which he eventually earned an annual salary of seventy-five thousand dollars, filled full pages with dialogue-heavy panels that reflected the rhythms of everyday life; in 1986, he became the first and only “alternative” cartoonist to win a Pulitzer. Matt Groening’s “Life in Hell,” which first appeared regularly in the Los Angeles Reader in 1980, wasn’t exactly a political cartoon, but when he took shots at Reaganomics, his work had more teeth than what was appearing in the daily papers. In the nineties, artists such as Derf and Tom Tomorrow infused political cartoons with more idiosyncratic artwork and cutting jokes.

Thomas Nast In this Harper’s Weekly cartoon from 1900, Nast lampoons the corrupt New York administration led by “Boss” Tweed and the Tammany Society. Universal History Archive / Universal Images Group via Getty Images

I discovered these nineties cartoonists in the run-up to the Iraq War, when I was nineteen, after having spent my childhood reading superhero fare. Suddenly my interests were political, and I found myself drawing editorial cartoons. My peers—people like David Rees, whose “Get Your War On” strip in Rolling Stone was thrilling and deceivingly simple, nothing more than clip art of office workers cursing about the war on terror—challenged the presumption that cartoonists needed to be trained artists to make political points. I started my career just in time to catch the tail end of the alt-weekly era, landing work in the Boston Phoenix and Seattle’s The Stranger. Cartooning in the Bush era felt important; wars without end and abuses of civil liberties were rolling out with high public approval, and reporters seemed to have abandoned their role as critics. More than a hundred years after Nast, the political cartoonists of this era made a strong argument for the field’s relevance by being right about the most consequential issues of the day.

But it was during the same period that alt-weeklies got swallowed by chains and revenues tanked across the newspaper industry. The idea that every newsroom should employ a cartoonist quickly dissolved. Without stable jobs, we met our audiences directly, on social media; many of my cartoons took off with tens of thousands of shares and millions of views. There was no money in posting online, but we learned to turn follower counts into merch sales and commercial gigs; eventually, some of us signed up for Patreon and Substack.

Cartoonists have in recent years gravitated more toward memoir and essay, freeing them from reacting to the news of the day.

Jules Feiffer In 1986, when Feiffer was a staff cartoonist for the Village Voice, he was recognized with a Pulitzer in Editorial Cartooning. Courtesy of the Village Voice

Tom Tomorrow I was inspired to draw political comics when I discovered artists like Tomorrow in the alt-weeklies of the Nineties. He and others of that era would become regulars at The Nib. Courtesy Tom Tomorrow, 1999

Along with the fire hose of social media attention came corporate capital. In 2013, I got my first staff job, as a cartoonist and editor at Medium. The role was vague and in constant flux, but the company was willing to experiment on an idea for an all-comics publication: The Nib. I’d edit it, Medium would fund it, and we’d make a new online home for political cartoons and nonfiction comics of all kinds.

The Nib was popular, reaching millions of readers every month. But Medium was not there to serve cartooning; cartooning was there to serve it. Not quite two years after it started, almost all the editorial staff was laid off. I took a buyout and retained The Nib. For a few years, I took The Nib to First Look Media—and then was laid off again.

Some online media companies are figuring out the future better than others. It’s become clear by now, though, that political cartoons won’t be along for the ride. They never really were. From the beginning, digital outlets rarely made space for political cartoonists as staffers or even as freelance contributors—and so the move away from print has permanently decoupled political cartoons from news journalism. Cartoonists often blame editors for their lack of interest and visual illiteracy—“words people,” we call them. I have often marveled that The Nib was ever able to exist at all. Surely, I thought, my top talent would be poached by media companies with deeper pockets. But it never happened.

David Rees From “Get Your War On,” published in 2001 in Rolling Stone. mnftiu.cc, 2001

In April, I quit political cartooning. I was thirty-seven, and I’d drawn about sixteen hundred cartoons over eighteen years. Deep burnout had set in over the course of the pandemic, and I decided to devote time to other kinds of work—genre comics, nonfiction graphic novels. It was mostly a creative decision, but there was also a financial incentive: while the market for political cartoons is shrinking, graphic novels are booming. Last year, graphic novels and comic books accounted for $1.28 billion in sales in North America. (The revenue from political cartooning, meanwhile, must be the combined income of the last thirty people doing it.)

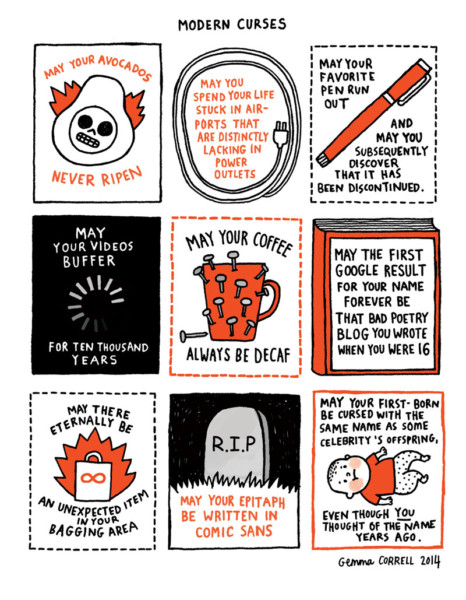

I am still running The Nib—an awkward perch for a retired political cartoonist. The magazine is small and completely independent, funded by subscribers. Many of the comics we publish aren’t political cartoons in the traditional sense, as many cartoonists have in recent years gravitated more toward memoir and essay, freeing them from reacting to the news of the day and giving them more space to make an argument. (Kendra Wells, a thirty-year-old Nib contributor, told me they view political cartoons as “stuffy old guys whose one-panel strips get into newspapers or Time magazine.”)

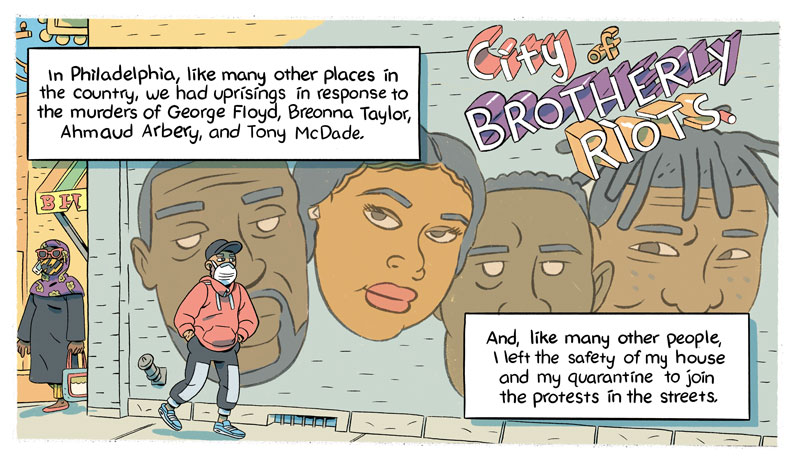

Yet the comics scene as a whole is more fiercely political than ever—far more than when I started drawing. Navel-gazing indie comics, once dominated by white men, have given way to nonfiction work by artists such as Niccolo Pizarro, Ben Passmore, Mattie Lubchansky, and Whit Taylor, who employ a variety of styles to comment on the state of the world. A perusal of my Instagram feed in May showed comic essays on queer identity, illustrations in support of Palestine, and an instructional comic from NPR on how bystanders can intervene in racist attacks on Asians. These comics are political—they just aren’t what we would call political cartoons.

Gemma Correll The early days of The Nib were exciting, though ultimately the publication was short-lived. I wanted to publish political and nonfiction comics by new artists. Correll was one of our first contributors and remains one of the most popular. Gemma Correll 2014 for The Nib

In June, many of us in the field were dismayed to find that, for the first time since 1973—and in one of the most politically tumultuous years of our lifetimes—the Pulitzer Prize board declined to issue an award for editorial cartooning. The AAEC issued a fiery statement to “urge radical structural reform of the award to evaluate modern opinion cartoons by 21st century standards.” As far as I was concerned, the decision confirmed that the stewards of old media just aren’t that into us anymore. I had left at the right moment.

I might dip into political cartoons again someday. Maybe I’m done for good. Maybe The Nib will collapse. Maybe my stress-induced chest pains will kill me. All I know is that, even if political cartoons are disappearing, comics with politics in them are everywhere. I’ve stopped caring what people call them.

Whit Taylor Excerpt from “America Isn’t Ready for a Pandemic,” 2018. The Nib

Niccolo Pizarro “Family Portrait,” 2021. The Nib.

Kendra Wells Opposite page: “More Benefits of Climate Change,” 2020. The Nib

Ben Passmore Excerpt from “A Good Old-Fashioned Screaming Match,” 2020. The Nib

Mattie Lubchansky Excerpt from The Antifa Super-Soldier Cookbook, published in 2021 by Silver Sprocket. Silver Sprocket, 2021

No comments:

Post a Comment