When I was six, a chance encounter with rhythmic gymnastics – all ribbons, sequins and smiles – opened up a sublime, sometimes cruel new world. By 12, I had quit. What had it all meant?

When I first caught sight of rhythmic gymnastics, I knew nothing of this. The reasons the sport is mocked – the sequins, the balletic dancing, the kilowatt-bright, beauty-pageant smiles of the gymnasts – were the reasons I found it delightful. I was six, sitting in my kitchen in Auckland, staring at the television. On screen, a gymnast at the 2000 Sydney Olympics tossed a bright red ribbon high into the air before catching it with astonishing ease. She was, to me, the height of womanly sophistication: beautiful, graceful, and covered in glitter. I dragged my mother into the room, pointed to the television and announced that this was the sort of lady I would like to become.

My mother was used to this. When I was a baby, she had moved us to New Zealand, while my father stayed in China, working to support our lives abroad. Like many immigrant parents, she wanted to provide her child with opportunities that she, growing up as one of four siblings in rural 1970s China, did not have. By the time I was a toddler, I was going to Chinese dance lessons, which I loved, and Chinese language classes, which I hated. As I grew older, I built up a near-maniacal collection of hobbies. I wanted to play piano, then violin. I wanted to be a ballerina. I was gripped by figure skating. Much later, my mother started worrying about the lack of male influences in my life and I was sent to after-school electronics clubs, where I spent a lot of time soldering.

These fixations were intense and brief. I usually lost interest within weeks. But with rhythmic gymnastics, it was different. Not long after my epiphany in front of the TV, my mother searched through the Auckland Yellow Pages and found a gymnastics club near our house. A few weeks later, we set off on a 15-minute journey through the suburbs for my first class. It was a good opportunity, my mother thought, for her daughter to get some regular exercise.

Later, when my gymnastics career was behind me, after all the accolades and the trophies and the gold medals, I would loudly reminisce about it to my friends, teachers, acquaintances, anyone who would listen – a 13-year-old wistfully reflecting on her glory days. But as I grew older, embarrassment crept over me. I wondered what it had meant to dedicate so much of my childhood to a sport that now seemed shamefully girly and unfeminist. This is a sport that first asks women to be graceful and model-thin, then scrutinises their every movement and facial expression for imperfections. The lifecycle of an elite rhythmic gymnast would please the most ardent misogynist. Ideally, you begin as early as possible, so you develop maximum flexibility before the grim reaper (puberty) comes knocking. Then, in the years when you are allegedly at your most beautiful, and certainly at your most emotionally insecure, you are expected to dazzle. Once you are no longer capable of dazzling, you exit the stage. Senior competitive gymnasts commonly retire in their early 20s.

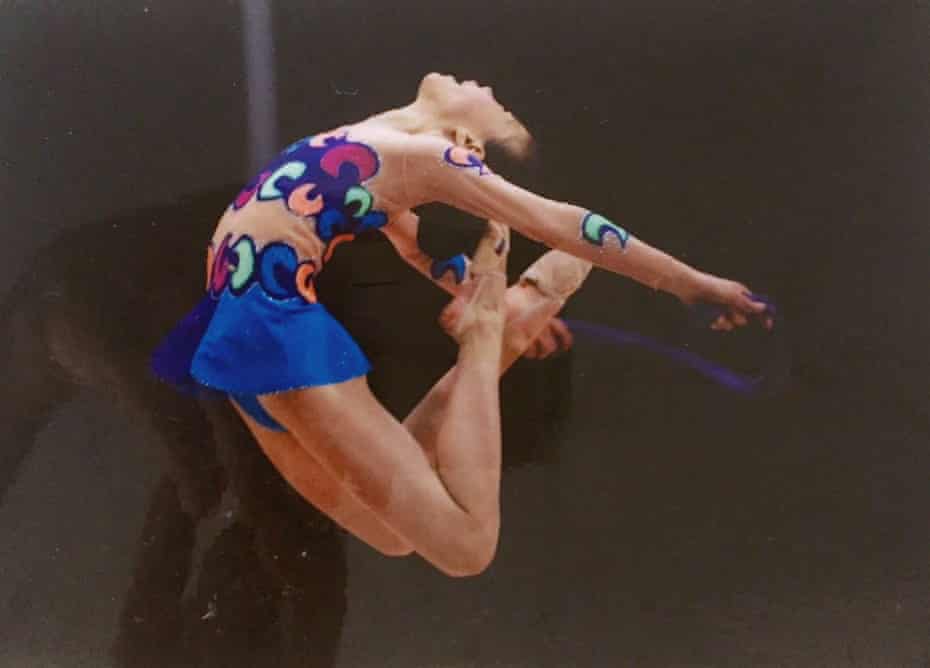

At university, I made peace with my childhood passion by presenting it cynically, showing friends photos of myself on the gym floor, clad in makeup and sequins, with an air that said, “Yes, I, too, have semi-read The Second Sex”. Mostly, though, when I looked at these photos, I felt old. One summer, watching yet another round of gymnasts getting their taste of Olympic glory, all of whom seemed to be rudely getting younger and younger, I phoned my dad in a panic, telling him that I had become a has-been. He replied that I was 18, and thus still had plenty left to live for.

Almost a decade on, I recently searched online for any remnants of my life in rhythmic gymnastics. Gone. I asked my mother if she still had any of the medals. Lost in an old house move. What about that time I was interviewed in the local paper? Gone, gone, gone. That child national champion, so driven and so athletic, feels like another person who somehow inhabited my body decades earlier, before bolting it without warning, shutting the windows and doors and leaving no trace. Was that even me?

Iwas hooked on rhythmic gymnastics from the very start. I loved the rush of feeling my body stretching and moving, propelled by the hope that I, too, might one day be as graceful as that ribbon-throwing Olympian. Under the tutelage of two kind teenage sisters, I began my education. Rhythmic gymnastics, I learned, is not just about sparkly leotards and ribbons; it is about sparkly leotards and ribbons and the ball, rope, hoop and clubs (in reality, two small batons). For each apparatus, rhythmic gymnasts have a separate routine.

To the six-year-old me, always prone to catastrophising, one of the most appealing things was that there were no terrifying, gravity-defying flips or tumbles. The movements, set to music, are instead rooted in dance and ballet. You have leaps and jumps; rotations, otherwise known as spins and pirouettes; and balances (just throw your leg out behind you to make an arabesque, then bend your knee and kick your foot towards your head, then catch it. Easy!). As you perform these movements, you must also effortlessly juggle, spin, throw and catch your ribbon or ball or rope or hoop or clubs. Yes, it is a real sport.

Judges score each routine by two criteria: the difficulty of the moves, and the execution of the performance. Afterwards, the gymnast, her face beaded with sweat and flushed with nervous euphoria, heads to the “kiss and cry” area to await her score. Thus rhythmic gymnastics combines the pleasure of seeing ludicrously skilled athletes test the limits of what the human body can do, with the campy theatrics of shimmering leotards and slickly gelled hairdos, and the psychological drama – heightened by the wait for the judges’ verdict – of reality TV, where behind the gorgeous spectacle lurks the shadow of a knife.

Internationally, rhythmic gymnastics is dominated by Russia, Ukraine and Belarus: Russia has won every Olympic gold for the past five games, and are favourites to win again in Tokyo this year. In New Zealand, it was a niche sport; underfunded, misunderstood, not the thing to pursue if you wanted mainstream recognition. You could be the best rhythmic gymnast in New Zealand but struggle to place internationally.

And yet, from that first lesson on, life in Auckland became, for me, about spending time in the back seat of my mother’s car being shuttled to and from gymnastics practice, forever stuck in traffic. The drive to my local club in the eastern suburbs wound past other childhood touchstones – my primary school, my favourite McDonald’s, the dodgy hotel with a buffet my friends and I would go to on birthdays, the public library. But the place that mattered most was the gym.

After a few months of practising, I was ready for my first competition. Watching gymnasts pile in from other parts of Auckland, then studying them up close through the fog of hairspray in the changing room, I grew nervous. Something you don’t see when watching gymnastics on television is that as one athlete is performing their routine, another is standing in the wings watching, psyching themselves up to go next. I remember these moments in the shadows more clearly than I ever do performing. Performing takes you into the realm of the familiar and rehearsed, allows you to get lost in the music and the delight of showing just how good you are at this thing. The waiting, however, is hell.

As I stepped out on to the mat, something strange happened. Facing an audience and a panel of judges, I bloomed. My body expertly followed the directions issued by my mind. I instinctively felt what jump went when. I remembered to flash my smile to the crowd. The rapturous delight of showing off, the sudden bravado that blasted my nerves away, the rush of feeling my body leap and jump and spin – all this was new. Total pleasure, shot through with a complete conviction in my own power. I wanted to feel this way again.

I won a bronze for one of my routines, and on the car ride home I held the medal tight to my chest. I had no expectations for what would come next. All I knew was that they had given a few prizes to a select few kids that day, and, on my very first try, I had been one of them.

What can I say? Did I, at six – at seven, at eight, at nine – ever sit down and think, “Yes, I want to embody a conventional vision of femininity in the uncanniest and most unsettling of ways?” No. I had simply wanted to be pretty. Follow the ideological road from a childhood defined by Barbie dolls and ballerinas, and you may find yourself pining to be a rhythmic gymnast: conventionally beautiful, perennially cheery and shunted away from public life at 22.

The lack of respect that rhythmic gymnastics receives is hard to separate from the gender politics of the sport. Rhythmic gymnastics is women-only and unabashedly girly. (Men’s rhythmic gymnastics does exist, but it is not recognised by the sport’s governing body.) The rules stipulate that gymnasts “communicate feeling or a response to the music with facial expression” to convey “strength, beauty and elegance”. In other words, rhythmic gymnasts must not only endure pain, but smile through it, too.

There is one version of this story that casts me as a victim of the patriarchy, obediently smiling through my suffering. Perhaps in a sense I was. But that’s not the whole story. It is easy to see how rhythmic gymnastics is constricting. What is harder to see is how liberating it can feel. When I was on the floor, there was a deep pleasure in letting the audience, and myself, know that I could triumph over impossible demands. Under the scrutiny of judges, competitors and the crowd, I knew that I was here to conquer. My smile felt less sweet and obliging than a dark challenge: go on, idiot, underestimate me.

Gymnastics unlocked something sublime and powerful, opening up planes of existence normally closed off to girls: the feeling of bloodlust pumping through my body, the hunger for glory, and the all-consuming joy of losing myself in something greater. Yes, these dark emotions were channelled through something extremely girly. But these hyper-feminine things – like gymnastics, like dance, like pageants – were, and remain, some of the few ways in which women can experience those feelings without censure.

At that first competition my performance caught the eye of coaches from a more competitive club across town. I had hit the big leagues. Now the drive took 45 minutes, juddering along a choked-up motorway before winding past the sprawling villas of Auckland’s central suburbs.

As the months passed, my leaps got higher and higher, my turns got more complicated and my splits became hypersplits (in which you put one leg up on a bench for a deeper stretch). Six months after my bronze, I won gold in a competition in Auckland. The next month, I won another. Then another. Soon we were far beyond my mother’s initial hope that I might find a hobby that would get me exercising. My coaches began teasing the prospect of international competitions – maybe even the Commonwealth Games, maybe even, whisper it, the Olympics. (“Maybe” being the key word: New Zealand rarely qualified.)

When I wasn’t training or competing, I was reading my way through rhythmic gymnastics websites and message boards. As I waited for the sites to load, I practised my splits.

While browsing one day when I was eight, I made a startling discovery. I read that by age 10 I would be past the golden period in life for flexibility training. At that moment, in my mind, the clock started ticking. I resolved to train harder so I would be prepared for the day my body would become a decrepit flesh cage – my 10th birthday.

Films about girls and sport usually share a common structure. There’s the initial encounter, followed by the arduous journey to greatness, which culminates in a final, glorious contest. Accompanying the protagonist on her journey is a group of supportive friends, some mean girl rivals, and inevitably, a boy.

Over the next two years, my life adhered to the sporting side of that script, but not the social one. Today I barely remember the people I met, the coaches and other athletes. What I remember is how it felt to win. The flesh-and-blood world felt far less compelling than the prospect of sporting greatness.

The other gymnasts I competed with were nice white girls from middle-class families that did not resemble my own. They were friendly, but we were not friends. I absorbed, like many immigrant children, a latent awareness of my difference, and thus a thirst to gain what others did not appear to need to fight for – acceptance. I was the proverbial contestant in the reality television show who was not here to make friends. I was here to win.

And there was never a boy. Boys did not magically rearrange the world to make it look more beautiful and more true. Boys did not get you written about and photographed for the local paper. Medals did.

I was in a battle against time: my body was fast on its way to being too old. I was in a battle against myself: each gold medal was a challenge issued by myself to keep up this streak. To an outside observer, I was a little girl in a sparkly leotard throwing a hoop back and forth, but in reality, my life in rhythmic gymnastics felt less like a sleepover-friendly teen drama than one of those hardboiled stories about a steely renegade on a single-minded quest – usually a man, hardened by middle-age, gripped by an obsession so pure and powerful that it alienates everyone around him. At nine years old, I was that man.

My peak, though I didn’t know it then, came at the 2003 national championships, which brought together athletes from all gymnastics disciplines for the most important competition of the season. On the first day, the gigantic Auckland arena was teeming with activity. Artistic gymnastics and trampoline competitions were held simultaneously, and a bang of the vault or a thundering rush of applause would bleed over into the already humming rhythmic gymnastics zone. It felt like attending a mildly out-of-control party full of inordinately flexible people.

And there, on the rhythmic gymnastics mat, I soared. My scores broke national records. I came first in every equipment category in my age group. During the prize-giving ceremony, a disembodied voice from a microphone echoed round the arena, announcing the results for my age group. To me, it was something like the voice of God.

I climbed on to the top podium trembling with glee. Then came the icing on the cake: I was crowned New Zealand’s 2003 gymnast of the year. My head was dizzy with excitement; I lost myself in the applause of the crowd. I knew even then that tomorrow the cycle would begin again – the hard-knuckled training, the battle against the ravages of time, the fear that any moment my winning streak might end. But those were tomorrow’s fears. At the top of that podium, I felt loved, perfect and immortal.

The better I got, the longer the journey to training. After the 2003 national championship, I moved to a new club that would prepare me for international competition. On the new hour-long drive, we would pass my old club on the way to the Auckland harbour bridge. Every time we crossed the bridge, I would turn my head to look at the towering blocks of the city we were leaving behind, slowly disappearing across the glinting blue-green sea.

I was now the youngest in a group of teenage girls who were occasionally distracted by the teenage boys who trained in artistic gymnastics on the other side of the gymnasium. I would watch my teammates pass them notes and linger for a chat in the hallway. I did not take part; the other girls sweetly told me that at nine, I was “too young”. But as I stretched in my hypersplits, obnoxiously convinced that boys were for other people who did not have my iron discipline, I felt very old.

The prospect of ageing weighed heavy. At the club, there was a largely unspoken expectation that you’d watch your weight, but at nine, I knew I was still safe. The trouble would come later, when puberty threatened to slow down my metabolism and render my body unsuitable for uninhibited jumping and spinning and running. (This fear wasn’t just a gymnastics thing – it was also how I heard teenage girls and women speak about their bodies in the world beyond.) The horrifying prospect of growing breasts hung over me like a dark, hideous cloud.

At this club across the harbour, the aura that surrounded gymnastics in my mind began to fade a little. Gossip and drama crept in, and I started to sense that lurking in the corners of this beautiful thing I loved lay hints of violence. In recent years, abuse in gymnastics has been well documented. Last August, New Zealand website Stuff published an investigation into the allegations of psychological and physical abuse of former artistic and rhythmic gymnasts. Athletes told stories going back to the 90s about having their bags searched for food, their bodies criticised and injuries ignored. Many alleged that they had been psychologically abused by coaches. In 2018, the US gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar was convicted of abusing at least 265 gymnasts over several decades; in February this year, 17 British gymnasts began a legal case against British Gymnastics over alleged physical and psychological abuse.

I didn’t experience anything like this, though I recognise the milieu that made these stories possible. Competitive sports lock you in a small world. For every jubilant victory, there are many heart-shattering lows: failing to catch your equipment, injuring yourself in training, trying your best but just not being good enough. In other settings, you might be encouraged to “see the bigger picture” – that there is a larger world out there full of other things you can do. But the buzz of competitive sports comes precisely because the sport, for those in it, is the whole picture. It is the source of your identity, the focus of your dreams. It is why, in far too many cases, abuse will be quietly tolerated or ignored. A lot of harm can be done by those in power when a world narrows like that. Add to that the fact that many of these athletes are young women who have likely, as I did, gone into the sport early on in their lives, and you get a setting ripe for cruelty.

My first, and last, international rhythmic gymnastics competition came in the summer of 2004, when I was 10. I boarded a flight with other gymnasts from my club and our parents, excited for what was to come. On the day of the event, athletes from all around the world piled into the stadium. I watched the two gymnasts from Russia nervously, and began to feel very small. Would my national champion trophy count for anything here?

I performed my routines the best I could. But halfway through one, a knot formed in my rope. I decided to smile through it. Afterwards, I discovered that the points I received for the movements I did after that were not fully counted, because I had done them with a misshapen rope. I got a terrible score.

I won a bronze for the ball, but did not place for my other routines. It was the same result as my first competition. Then, I had been delighted. Now, I felt heartbroken. Like a teenager experiencing their first breakup, I fell into an existential tailspin. What was all the point of this? What was the point of life? There’s always next time, my coach told me on the plane home. All I could do was endlessly replay my split-second decision not to untie my rope, stewing in self-hating regret.

The glow was gone. The world of rhythmic gymnastics, which had once shone to me in rainbow-bright hues of leotards and the glittering gold of trophies, faded to grey. Perhaps it was because of my defeat, or because I was growing older, but life felt more difficult after that. While I still loved being on the gymnastics mat, I was starting to realise how much was beyond my control. My mother, who had taken a full-time job, was finding it increasingly difficult to shuttle me to training and competitions. She also missed her friends and family at home, and needed time to rest. I took a break from the sport, and a year later, when I was 11, we moved to Hong Kong.

That was not quite the end. My family in China had long been proud of their western-raised gymnastics champion, and I was suffering with an identity crisis of my own. Without gymnastics, I didn’t know who I was any more. A few months after the move, we found the nearest rhythmic gymnastics club. It was in Shenzhen, a megacity in mainland China across the border, reachable by an hour-long subway ride.

After the coach – young, stern, sceptical – had evaluated my abilities, I was placed with a group she judged to be my Chinese-trained equivalents: five-year-olds. I hated this humiliating confrontation with my past-its-prime flesh, my useless body that could not bend in the way it was supposed to. I went to two sessions before deciding that this was not fun any more. I suppose that’s one way in which I have surpassed my childhood Olympic heroes. While they took their leave from the sport at 22, I retired at 12.

Two decades later, my childhood visions of bodily decay have long since come true. Running for the bus leaves me breathless, and if you were to throw a ball at me, I would probably duck. After quitting rhythmic gymnastics, I stayed away from competitive sports. It wasn’t until lockdown last year that I started to do regular exercise again, mainly out of boredom. This spring, after feeling a dull ache in my left foot, I called my GP. He gently told me that over the past year he had seen many injuries from people “not used to much exercise” who had suddenly dived into high-intensity routines. There didn’t seem much use in telling him that as a nine-year-old I could place my foot on top of my head. And yet I still wanted to.

For many years, I thought of my life in rhythmic gymnastics as a weight to bear. It was a difficult thing to have been judged the best in a country at the age of nine. Where were you supposed to go after that? And all that training, all those competitions, all that glory: it felt meaningless, like a waste. I wanted it to have left me something lasting, some calling card that could be issued to everyone I met that said: “I was once a national champion.”

These days, it doesn’t seem that way. The whole experience – the accelerated lifespan of my athletic self, compressed into half a dozen years – seems more valuable, a hyper-condensed lesson in loss, humility and absurdity. The pointlessness of the sport feels strangely poignant.

On the rare occasions I’ve come across rhythmic gymnastics as an adult – getting sucked into a YouTube hole or watching it during the Olympics – it has been like meeting a childhood crush, only to realise they’re weirder-looking than you remember, and a little awkward. And yet, if I continue watching, I feel it again. I close my eyes and remember all the moments when my younger self stood on that top podium, garlanded with medals, feeling as if she had unlocked a sphere of living that was sublime and free.

No comments:

Post a Comment