Your gut microbiome weighs about 2kg and is bigger than the average human brain. It’s a bustling community of trillions of bacteria, archaea, fungi and viruses, containing at least 150 times more genes than the human genome. We are filled to the brim with microbes, which form microbiomes on our skin, in our mouths, lungs, eyes, and reproductive systems. These have co-evolved alongside us since the beginning of human history. But the gut’s is the largest and most significant for our short- and long-term health. It is massively complex and its residents vary enormously from person to person. According to a study in 2020 by the European Bioinformatics Institute, which pooled more than 200,000 gut genomes to create a genetic database of human gut microbes, 70% of the microbial populations it listed – 2,000 species – hadn’t yet been cultured in a lab and were previously unknown.

Studies suggest having a diverse population of gut microbes is associated with better health. But when human populations urbanise, microbial diversity declines. Professor Jack Gilbert is an award-winning microbiome scientist at the University of California San Diego and author of Dirt Is Good. “Over the past 80 years and since the dawn of antibiotics, there has been multi-generational loss of microbes that appear to be important for human health,” he says. “They’re passed from mother to child [during birth, via breastmilk and skin contact] throughout the generations, but at some point in the last three or four generations, we lost some. We’re not entirely sure if the cause was our lifestyle, our diet, cleanliness in our homes or the use of antibiotics. We’re also missing certain immune stimulants that people in the developing world have plenty of.”

Gut microbes do things the gut can’t do, liberating or synthesising nutrients from food, especially from plants and their polyphenols, living off non-digestible substrates, producing thousands of metabolites – useful chemicals –and making vital short-chain fatty acids that are involved with immunity, with keeping the gut and colon healthy, with moderating the body’s inflammatory responses and with the metabolism of glucose. To do this, microbes need about 30g of fibre a day, but the average intake in the UK is just 10-15g. Is this why modern, low fibre, ultra-processed, high-sugar diets seem so problematic for human gut health?

“It’s very hard to know exactly what it is in junk food that is causing a problem,” says Spector. (When he talks about junk food, Spector means most prepared and packaged foods – including things such as vegetarian lasagne.) “It’s not the fat, carbs and protein, it’s the extra chemicals. The data is probably best for artificial sweeteners that are derived from things like paraffin and the petrol industry, so our bodies and our microbes are not used to breaking them down. But it could be other stuff, like the enzymes you don’t get on the label, or emulsifiers. There are few studies on emulsifiers, and nearly all in animals, but they show that you get reduced diversity and more inflammatory microbes. The idea is that they’re doing the same as they are in cooking: sticking your microbes together, creating an emulsion. Or it could be the lack of fibre and the fact that everything is refined. We haven’t nailed it down, but I think it’s safe to say that ultra-processed foods are bad for your gut microbes and we should avoid eating them regularly.”

The great opportunity – but also the great difficulty – of gut microbiome science is that poor gut health is associated with such a vast range of conditions, from obesity and degenerative brain diseases to depression, inflammatory bowel disease and chronic inflammation. “The microbiome is associated with everything,” “Pick a disease, it’s associated,” says Kinross. The microbiome is like a convergent science – you have to be an ecologist, a geneticist, a bioinformatician, a clinician and an epidemiologist, to try to make sense of it.”

“Everything we’re doing now is scratching the surface,” says Spector. “We are maybe 10% of the way there, because every week, we’re discovering something new. Humans want an easy answer [to improve our gut health], but you shouldn’t take anyone seriously who doesn’t say it’s complicated,” he says. “There’s a massive industry that needs a simple message to sell its products. They want to say all you’ve got to do is eat this bar, this yoghurt or this protein drink.”

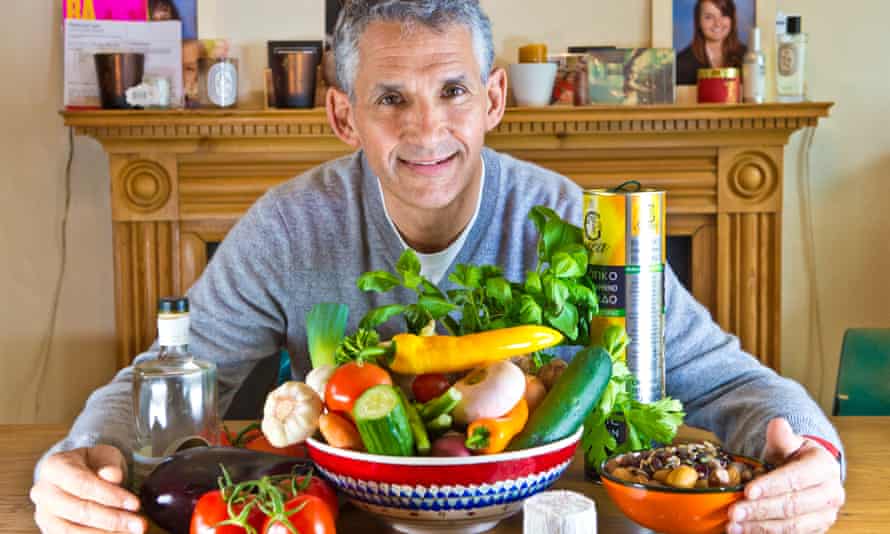

Spector does, however, have skin in this game. He and Jonathan Wolf, a machine-learning and data science expert, founded ZOE four years ago with the aim of creating personalised diets based on what an individual’s specific gut microbes needed. It has already launched in the US and later this year people in the UK will be able to buy into the ZOE testing process. The price for the UK programme hasn’t yet been finalised, but in the US it costs $360 for six months. (The #bluepoopchallenge, started by ZOE, is free, though – the recipe for blue muffins, which hundreds of thousands of people have already used to track their digestion, is on the ZOE site.)

The theory behind ZOE is that our varying gut microbes explain, at least partially, the big differences in individual responses to food: why one person who eats a lot of fat or sugar doesn’t put on weight, while another does, or why some of us can tolerate particular foods better than others, even why particular people become obese. If we knew which microbes were associated with a higher risk of obesity – because they’re more efficient at accessing calories, perhaps – or which best protect brain health, then we could tailor our diets to feed them.

Spector’s 30-year-long study of 15,000 twins, TwinsUK, and his PREDICT studies have shown that even genetically identical people respond to the same foods very differently (our microbiomes are so variable that twins share only 30% of the same gut microbes). By feeding participants the same meals on different days, he was able to show that responses to the same meals also vary hugely between individuals, influenced by both the microbiome and genetics. This matters, says the ZOE team, because our response to food is linked to our risk of heart disease, type 2 diabetes and obesity, but also because it blows apart the tired and useless mantra “calories in, calories out”, which doesn’t make sense in a world where two people’s blood glucose levels can be hugely different after eating the same slice of cake.

Microbiome testing has been around for a while, but it’s never been particularly useful as a way for people to understand what’s going on inside their bodies because not enough is known about what microbes do or how they interact. As Dr Megan Rossi, AKA the Gut Health Doctor, a dietitian and research fellow at King’s College London, and author of Eat Yourself Healthy, puts it: “I see patients in clinic with [microbiome] tests, and it would really help me to be able to use them to get patients better, but they just don’t have clinical translation. I absolutely believe in the future they will. But we’re not there yet.”

Spector hopes his tests – which don’t just test for microbes, but also assess blood fat and blood glucose responses to specific foods – will change this. “We’re just starting to get to the point where we can suggest individualised foods. This is not just isolated microbiome testing,” he says. “We have trials in place to quantify this, but the initial results are exciting, with nearly everyone reporting weight loss and improved energy levels without any calorie counting or traditional weight loss methods. Previous microbiome tests have been sub-optimal [but the] ZOE approach is completely different: using state of the art sequencing allows us to detect species and strains and find strong associations between these microbes and both foods and health.”

This is done via algorithm, as Wolf explains, combining his machine learning with the microbiome science. “But if we were going to do this, we were going to do it the right way; to carry out what’s turned out to be the largest in-depth, nutritional science study in the world, in order to collect the raw data for the machine learning,” he says. “And that meant getting thousands of people to do very intensive studies. We identified 30 key microbes that are indicators of health and linked to specific foods,” he says of his PREDICT 1 study, co-created with a team at Harvard and the University of Trento, involving more than 1,000 people and published in Nature Medicine.

If our microbes are so important, can’t we just package up the right ones and put them in a pill? Professor John Cryan is chair of the department of anatomy and neuroscience at University College Cork and principal investigator at the APC Microbiome Institute. “We will get strains of bacteria to have beneficial effects,” he says, but he laughs when I ask him how he feels about probiotics. “That’s like asking me, ‘Do I like drugs?’ If I have a pain in my head, I want to take a drug that has efficacy for headaches. I wouldn’t just randomly pick one. But that’s what we’re doing with probiotics right now. The science needs to catch up. We’re lumping them together as if they’re the all the same thing, but, like drugs, they may do very, very different things. We need to get precision into probiotics and then I can be excited about them. But most of what’s out there is complete nonsense.”

While many microbiome scientists don’t have much time for the commercial probiotics industry, there is growing interest in what are now called live bio-therapeutics – probiotics designed and tested to be used clinically (none are yet licensed for medical use in the US or Europe). Professor Ingvar Bjarnason is a gastroenterologist who has conducted double-blind, placebo-controlled studies on specific probiotic blends. “There is no data whatsoever for the vast majority of the probiotics on sale,” he says. But he is curious about a blend he has already studied for its impact on IBS, called Symprove, and its potential as a treatment in hospitals for acute Covid. “We think of Covid as a virus of the lungs, but the microbiome of people with acute Covid can be altered very severely. Very ill people with Covid have a cytokine storm where they have multi-organ failure, due to an enormous amount of really strong inflammatory markers. The suspicion is this inflammation may come from the gut, and when the gut has been examined in acute Covid patients, it is abnormal.”

A very small Italian study using a similar commercial probiotic, Sivomixx, piqued his interest after it suggested acute Covid patients treated with it might be less likely to end up in ICU or to die, and eight times less likely to suffer respiratory failure. Bjarnason is hoping to start a larger study in the next few months.

Several other gut bacteria are also being studied as biotherapeutics. “One of the bugs that appears to have disappeared from Europeans, North Americans and Chinese people over the last 50 years, is bifidobacterium longum infantis,” says Jack Gilbert. This bacteria seems purpose built to digest oligosaccharides in breast milk, sugars which babies born in developed areas simply poo out. “That’s why in the western world, baby poo is sloppy, whereas in the developing world, baby poo comes out pretty solid, more like adult poo, because their breast milk is being digested by the bacteria in their intestine – kids growing up in Africa and certain parts of Southeast Asia Africa and certain parts of Southeast Asia that aren’t developed have tonnes of bifidobacterium longum infantis. If we put it into a mouse and feed it breast milk, it digests all the sugars. There are clinical trials ongoing, putting this bug back into children, especially in preterm infants in neonatal intensive care units, to see what impact it has.”

The final frontier for gut microbiome exploration is its relationship with our brains, something the new fields of nutritional psychiatry and psychobiotics are digging into. We already know the gut has its own nervous system, the enteric nervous system, and contains 100m neurons. We also know the gut-brain axis, via the vagus nerve, shoots neurotransmitters produced within the gut around the body and to the brain, which is why Cryan’s lab has studied the impact of particular bacteria on sleep and how certain types of fibre can improve complex cognitive processes.

Kimberley Wilson is a chartered psychologist and author of How to Build a Better Brain. She uses nutrition as part of her treatment plans. “The short-chain fatty acids produced from microbial fermentation of fibre [in the gut] are quite similar to some mood-stabilising prescription drugs,” she says. “Some of the association that we see between healthier diets and better brain health could be because your microbes are producing psychoactive substances from your diet to help stabilise your mood. In the future, we might actually prescribe certain types of fibres for certain mental health conditions.” For now, she simply prescribes a lot more fibre to feed what many scientists now consider our second – much larger – brain. “The more fibre you eat, the more substrates the microbiome has available. And the better off we’re going to be, psychologically. I think that’s incredible.”

Improve your gut health

Seven simple ways to keep the right balance

Eat more fibre Most of us eat only half the recommended 30g a day. But start slowly – our guts don’t like rapid change

Eat the rainbow Choose colourful fruits and vegetables and try to eat

30 different plants, nuts and seeds every week

Eat foods rich in polyphenols These include dark chocolate and red wine

Eat fermented foods Tim Spector favours kombucha, kefir and kimchi, as well as unpasteurised cheeses

Eat more omega 3 New research suggests a relationship between gut microbes, omega 3 and brain health

Let kids play with dirt and dogs Jack Gilbert’s research has shown that since the gut’s population is seeded in early life, allowing small children to dig in soil and play with domestic animals can undo a lot of the damage modern lifestyles do to our microbiomes

Avoid processed foods Cut back on salt and sugar, both of which seem to affect microbial diversity in the gut

Leon Happy Guts: Recipes to Help You Live Better by Rebecca Seal and John Vincent (Octopus Books, £16.99) is available for £14.78 from guardianbookshop.com

No comments:

Post a Comment