A great teacher can change a child’s life. As this school year ends, we ask cultural figures including Charles Hazlewood and Kerry Hudson to remember a teacher who inspired them

This year, more than any year, teachers deserve our thanks. It’s too soon to know the true cost of the pandemic on students’ and teachers’ mental health, but it’s clear that the lack of clarity, the incompetence and mismanagement of examinations, the bias and the appalling lack of knowledge shown by government about the majority of children and young people’s experiences of education, have had a profound effect on attainment, on confidence, on a generation’s love for learning. And all the time, from those first uncertain days in March 2020 to this imminent end of term in July 2021, teachers have been on the front line – trying to support pupils, to teach students, to decipher the mixed messages coming from politicians and local authorities, withstanding unwarranted and ill-informed attacks from sections of the media. Because, in the end, teachers have done their best to keep things going for the students in their care, in spite of the obstacles put in their way. They have been frontline staff without the protection, they have kept a watching brief for vulnerable children to make sure they didn’t slip through the cracks. A year and a half of never quite knowing where they stand, what the rules are, what they are allowed and are not allowed to do. Many months of educational leaders not being listened to or being criticised by those who know nothing about what it means to stand up in front of a class of 30 boisterous 12-year-olds and bring history to life, maths to life, music to life.

Some of us loved school, others had a terrible experience or look back with indifference or a faded sense of relief that their lives are no longer dominated by the ringing of a bell dividing the day into lessons. I was lucky enough to have some fantastic teachers at my 2,000-strong girls’ comprehensive school, fortunate enough to be at a school that understood that theatre and music and painting were as important as arithmetic, science and technology, a school where there was a library and a playing field.

From the teachers who remained after school every day to rehearse the school play, or run the rounders club, or the hockey team, almost all of us can remember one particular teacher, someone who saw promise when no one else did, who gave support or sparked interest in a subject – woodwork, football, drama, physics, computing, English literature, art, modern (and ancient) languages. Well-judged words on an end-of-year report giving a child confidence, seeing something that everyone else has missed, giving encouragement to stick at it and to be oneself. Two stand out in my mind: my Latin teacher Mrs Hooper, brilliant and political, taught us as much about Roman dictatorship and Greek democracy as about conjugating verbs; and my gentle English teacher, Miss Lowther, who, when the lesson was done, could be persuaded to tell us stories of her time working in missionary schools in south-east Asia in the 1930s. I can still remember the sound of their voices, that peculiar atmosphere in a classroom mid-afternoon, Mrs Hooper’s fierce commitment and Miss Lowther’s halo of white hair, the scratch of chalk on a blackboard, listening.

My 90-year-old mother-in-law, known to everyone locally as Granny Rosie, began her career as a teacher in 1947. Having raised enough money to support herself at teacher training college, she was first employed by West Sussex county council for £3 a month. Each morning, she’d present herself at County Hall in Chichester to be sent anywhere in the district on her bicycle for a day’s work. For the next 40-odd years, she taught in primary schools in Hampshire, in Sussex and, for a term, in Devon, finishing her career in the 1980s at the local school for children with severe and complex educational issues. Rosie takes everyone as she finds them, sees all the things a person can do rather than focusing only on the things they can’t; she approached every teaching day with energy and commitment and, most of all, fun. Her pupils loved her and even now, when we walk through town, parents of children who were once in her care will stop her wheelchair to say thank you, to say how they have never forgotten her kindness and her interest.

That’s it, really. Teachers can – and do – make a difference. Sometimes, the difference. So, in the spirit of saluting all the extraordinary teachers of today who’ve kept our schools going over these strangest, and sometimes darkest, of times, who’ve kept students motivated and hopeful, here are some thank you letters to teachers in the past who made that difference. Kate Mosse

Kate Mosse is the founder and chair of the Women’s prize for fiction and the author of 10 novels, including Labyrinth, The Taxidermist’s Daughter and The Burning Chambers. Her latest book is An Extra Pair Of Hands, a memoir about caring for ageing loved ones (Wellcome Collection/Profile Books)

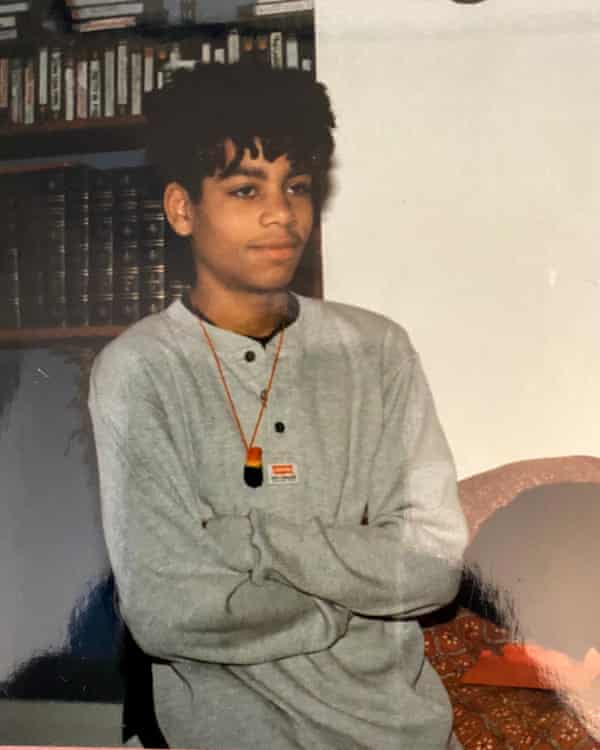

Ben Bailey Smith: ‘This was History with a capital H and an NWA soundtrack’

Ben Bailey Smith began his career as rapper Doc Brown before moving into acting, standup comedy, screenwriting and children’s books. His latest book for children, Something I Said, was published in June by Bloomsbury

Dear Mr Lyle and Ms Dauphin,

Remember that slightly crumbly old state school, Hampstead School? It always made me chuckle because it wasn’t in Hampstead, it was in Cricklewood, and if you remember anything about north London in the 90s you’ll know why that’s funny.

Put simply, people from Hampstead didn’t go to Hampstead. It was rough and ready to say the least but – in the late 90s anyway – it seemed to produce the best kind of young adults at the other end. Maybe not world-leading academics, but rounded, progressive, street-smart folk who could hold their own in any room with anyone from any walk of life at any time.

I often think about the alchemy of this. It was a place where I experienced some of my most galling social moments: unrequited love, teasing, bullying, PE changing rooms, endless detentions and worst of all, no uniform. If you’re like me and your mum didn’t believe in spending more than £15 on trainers, you’ll feel my pain. And yet, I was regurgitated out at the other end with an inner strength and sense of purpose that I don’t think I even realised I had until I entered the world of further education and work... Y’know, like when you work with that guy from the countryside who’s never been friends with a black person and thinks saying everything in a comedy Indian voice is hilarious, or when you study at uni alongside that private school guy who’s in awe at how you managed to develop morals despite having been to a comp… Hampstead grads always knew what to say.

There were, of course, a plethora of unquantifiable elements that made the Class of ’96 this way. It was not just one thing. Ours was a microcosm of what felt like the fruit of the London experiment – every type of kid you could imagine thrown into the mix in the hope that good old British tolerance would prevail. And I have to admit, it very much did.

No small parts of this heady concoction were you, my two history teachers, Gary Lyle and Helen Dauphin. That rarest of rare breeds at the time: both black, both young, both fiercely intelligent, both determined not to leave the strugglers struggling. Back in the days when the curriculum could be bent to a smart teacher’s will, you operated in spectacular tandem, peeling back layers of the old stories written by victors and wowing us with dynamic tales we hadn’t heard: the New Cross fire, the Brixton riots, the Middle Passage, the oppression inherent in governing. This was History with a capital H and an NWA soundtrack. And although there was never any favouritism, if you were a young black boy who daydreamed, passed stupid notes or generally goofed off (raising my hand here), you came down extra hard on us.

Now, I’ll be honest. I didn’t excel in history. Crucially, though, the desire not to let you both down – the distinct feeling that you really gave a shit – pushed me to find worth in my work and worth in myself. I scraped a pass, jumped into A-levels in English and theatre and forgot all about stupid old maths (what? I’ll hire an accountant), boring old science (I’m sure someday they’ll invent a phone or something that can solve problems for me) and history.

But I never forgot you – my two amazing history teachers who taught me not just about where I came from, but where I could be going.

With love and respect,

Ben Bailey Smith

Kerry Hudson: ‘I didn’t have a computer, so you sat in your office with me while I typed my Ucas form with one finger’

Writer Kerry Hudson was born in Aberdeen in 1980. Her novels include Tony Hogan Bought Me An Ice Cream Float Before He Stole My Ma and Thirst. Her most recent book is the memoir Lowborn (Vintage)

Dear Ian Gordon,

I liked learning. But a chaotic childhood and the subsequent wild teen years didn’t give me much of a chance. School felt irrelevant – and often downright hostile – so when I left at 15 it made sense to work as a waitress, to earn some money for the first time in my life. That is until I began to realise I was grinding myself into an even deeper hole.

I came to believe if I could get to university, mostly if I could get to university in London, then my horizons would be wider and life would begin. So, at 19, I joined up for a BTEC in performing arts. The course took place in Lowestoft in a little community theatre by the sea called the Seagull theatre. You, in your work boots and jeans, the spit of Kirk Douglas, always made us feel welcome. There were about 10 of us and each one had reasons we might not succeed the way other kids are expected to. Indeed, we might not have, except for you. You who were fiercely determined that we were not just going to make it through that course but be truly educated, creatively nourished and be exposed to all sorts of art.

The course was really hands-on. You taught us acting, lighting, stage directing, clowning skills, stage fighting and scriptwriting. We did performances in the local community. You took us on trips – not to watch stale West End musicals but to the most innovative dance and theatre. You introduced us to films and books we might never have discovered on our own and despite the assumption that a “girl like me” couldn’t appreciate those things you knew I could and they inspired me to expand my thinking.

I honestly don’t believe you viewed being a teacher as a job. Looking back, your teaching feels like it was a radically political act. You taught kids from poor or complex backgrounds who might have been abandoned in another sort of educational setting and showed them what they might do if they chose to. Crucially, you believed we could do anything, so I believed we could do anything too. You touched so many young people’s lives over the course of your career.

I did get to university, thanks to you. I remember struggling to fill out my Ucas form. I didn’t have a computer at home, I didn’t even know how to use one, so you sat down with me in your office while I typed with one finger, helping me with my personal statement. You gave so much of your time and attention to all the students, just to make sure that we were getting through, that we would achieve what we were capable of.

Obviously, I didn’t end up an actress, but the lessons and creativity you taught me, and the art that you gave me access to, have inspired me throughout my career. When I sat down to write my first book, having never dreamed of writing a novel, I knew, deep down, I could do it, because you had told me I was capable of doing anything I put my mind to.

We met up again five years ago in a coffee shop in Walthamstow. Just getting to say thank you meant the world to me. To be able to say: “I wouldn’t have been able to do any of this if it weren’t for those two years with a teacher who really nurtured me and believed in me.”

It means as much today to be able to say thank you. Thank you for investing in me and all of the other young people who you taught over the years – for your commitment to ensuring that kids from poorer backgrounds, with less-than-shining academic records, could consume and make and be truly inspired by art and that, ultimately, could enable us to be whoever we wanted, no matter what society told us.

With admiration and gratitude,

Kerry Hudson

Michael Longhurst: ‘Once when it all got too much, you told me that it wouldn’t always be like this. And you were right’

Michael Longhurst grew up in Bromley, south-east London in the 1990s. He is now the artistic director of the Donmar Warehouse

Dear Ms Withers,

How are you? It’s been more than half a lifetime. I’m writing from rehearsals for the West End revival of Constellations, thrilled to finally be making theatre again. You taught me English, in the mid-90s, at the now-shutdown comprehensive St John Rigby, in Bromley. I hope you’re surviving the pandemic? During the first lockdown I could hear my neighbour teaching on Zoom and was in awe of the stamina and skill it took to inspire class after class over the internet.

Remembering our time together, it probably needs acknowledging how challenging St John Rigby was. Made briefly infamous by our ex-nun headteacher embezzling funds to the tune of half a million (later immortalised by Pauline Quirke in the BBC’s The Thieving Headmistress), by the end, the buses didn’t stop there and the police seemed to have their own parking space. I didn’t fit in; I’m sure it wasn’t your ideal job either. But I wanted to write to say thank you for the profound effect you had on my life: helping a sensitive, eventually-to-discover-he-was-gay kid to find his tribe and career path. One time when it all got too much, you told me that it wouldn’t always be like this. And you were right.

The Portakabin where you taught us was a lunchtime refuge, your perfect copperplate handwriting emblazoned on the chalkboard; you furnished us with scenes and plays and left us to rehearse. My Oberon, king of the fairies, however appropriately cast by you, was somehow both self-conscious and hammy (it would be several more years before I would ditch acting for directing) but I vividly remember a trip you organised to see an RSC’s A Midsummer’s Night Dream at the Barbican. Those automated auditorium doors closing in sync as the lights went down – and fairies wildly cavorting with a donkey in upturned umbrella-bowers that descended from the ceiling. Seared in my memory, it fired my imagination for theatre and the syllabus, making the play alive to me. I remember us all – even the hardest back-of-the-coach boys – being wowed by your fabulous full-length evening gown on a school night! It was a night that changed me and began a love of theatre.

As arts education comes under further attack, it needs to be acknowledged that artists aren’t born but nurtured and empowered through opportunity, investment and exposure. We’re mounting our first Donmar schools tour to local comprehensives, to try to make sure young people don’t miss out on transformative theatre experiences. I hope the students have a teacher as amazing as you to guide them to their future at this challenging time. Wish us luck.

Affectionately,

Mike Longhurst

Sathnam Sanghera: ‘I don’t remember ever asking for help but you sensed how much I needed it’

Sathnam Sanghera was born to Punjabi parents in 1976 and raised in the Midlands. He is author of the 2009 memoir The Boy With the Topknot and this year’s nonfiction bestseller Empireland

Dear Robin Roberts,

It was Catch-22 by Joseph Heller that first got me into literature and writing, taught by you for English GCSE at Wolverhampton grammar school in the 1990s. The book is so naughty and anti-establishment and I connected with you over that humour. You took an interest in me and developed my love of reading and you remained my friend for life. I don’t remember ever asking for help but you sensed how much I needed it.

When I was studying for my A-levels, my sister had a schizophrenic breakdown. There was a ricochet effect between her and my dad – who also had schizophrenia – and things got bad. I had no money and my friends’ houses were too far away to get to, but I always knew that I could walk to your house. Severe mental illness scares people and most run for the hills, but I see now that you and my mum conspired to protect me from the pain. The night my sister was sectioned, my mother ensured I was at yours so I wouldn’t witness the worst.

When you realised I was struggling, you took me on school trips even when I wasn’t meant to be on them. The trip you took me on to Cornwall blew me away. It was the first time I’d camped, and the first time I’d seen sea so blue. I couldn’t believe such beauty existed in Britain. You also gave me my first glass of red wine and good advice about girls. After my first break-up you patted me on the head and told me it would carry on like this and I’d be fine. You were right.

Perhaps I’d be concerned if I heard about a teacher behaving this way nowadays, but I also hope teachers still get the opportunity to do what you did – to fill the gap for kids in trouble. I always thought you were very cool and didn’t give a fuck. Your humour always got me. I remember when I was filling in my Ucas form with you. One question was about jobs we’d done. I’d actually been working illegally in a factory for five years and you suggested we just write that down. So I answered a question about “nature of employment” with “illegal child labour”. I still got into Cambridge. The first in my family, the son of an illiterate labourer, going to university.

Although I thanked you, I don’t think I ever thanked you enough. About a month before you died I emailed to ask if I could take you to Rome as I’d never been and I was feeling bad that I hadn’t seen you properly for a while. You replied that you’d love to but you had a terrible cough. You were dead within the month of lung cancer. I’m glad that the last message I sent you was a loving one. After you died I found you’d kept all the letters I’d ever sent you. It’s a shame you didn’t get the chance to read this one – but I also hope it’s a good final note. A letter to say thank you for saving me.

Love from,

Sathnam

Charles Hazlewood: ‘You taught me about baroque counterpoint, but played piano like a death metal guitarist’

Charles Hazlewood is a conductor, composer and founder of the Paraorchestra, the first in Britain to feature disabled and non-disabled professional musicians. He went to primary school in Gloucestershire and then to Christ’s Hospital school, a charitable private boarding school originally founded for homeless children in the City of London

Dear Mr Edmonds and Mr McKelvey,

I was a very traumatised child, a survivor of sexual abuse, and I was forever searching for adults who felt safe but also inspiring. Mr Edmonds, you were one of them. I remember your music lessons from primary school so clearly. You would sit my class on the school hall parquet floor and blast out music while you sat at the back and chain-smoked. This was the late 1970s, when music was absolutely siloed into “classical” and “popular”. But you swam against the tide. You taught me about baroque counterpoint, but played piano like a death metal guitarist and a shaman. Thanks to you, I’m probably the only conductor in the world whose introduction to impressionist music was via Japanese electronica. I feel certain that something of your spirit lives in me. I’ve made a career as a conductor but, my god, I’m obsessed with Björk and Madlib as much as Verdi.

It was at senior school that I met you, Mr McKelvey. You were director of music at Christ’s Hospital and you took me under your wing. The abuse I had suffered meant I was angry and unmanageable. I had always been a choir boy, but when my voice broke I became completely rudderless. I stopped trying and lost my way.

One day when I was 15 I went to the chapel choir rehearsal (having not darkened its door for a while). You didn’t show up, so after 10 minutes I decided: “Screw this, I’m going to take the rehearsal.” When I started conducting the choir, it was a Damascene moment. I realised this was what I was here to do. I was riding this wave of sonic ecstasy when, suddenly, the organ started. Mr McKelvey, you were hiding in the organ loft all the time, just waiting to see what I would do.

Even though we’d never had a conversation about me conducting, you could smell it was the right thing for me and found a way to make it happen. From that moment on it was clear what was best for me. I became organ scholar at Keble College, Oxford – just as you had been an Oxford organ scholar in your day.

Thank you both for being the most abundantly safe, caring presences in my early life. Thank you for unlocking a world of possibility. You saw the potential in me and helped me find out that music was my safe place and let it work its magic on me.

With love and gratitude,

Charles

No comments:

Post a Comment