He dominated state politics for 25 years with bayou charm, razor-sharp mind, quick wit

A relaxed Edwin Edwards leaves the Federal Courthouse grounds in Baton Rouge after showing up to give his reaction to the indictment handed down against him today. Former Gov. Edwin Edwards is indicted. U.S. Attorney Eddie Jordan talks to reporters outside Federal Court in Baton Rouge after his grand jury handed down its long-awaited indictment of Edwin Edwards. Friday, November 6, 1998

- G. Andrew Boyd

Former Louisiana Gov. Edwin Edwards, standing with his wife, Candy, left, and daughter, Anna Edwards, listens to a question from the media Monday, Jan. 8, 2001, on the steps of the federal courthouse in Baton Rouge, La. Edwards, was sentenced to 10 years in prison and fined $250,000 Monday for extorting payoffs from businessmen applying for riverboat casino licenses.

- STF

Former Louisiana Gov. Edwin Edwards arrives at the Ecumenical House, a halfway house, to begin serving the remainder of his prison sentence, after being released from the Oakdale Federal penitentiary after serving eight years for a corruption conviction, in Baton Rouge, La. The 83-year-old Democrat completed six months of home detention and regular reporting to the Baton Rouge halfway house, one of his remaining requirements after being released from federal prison earlier this year. 2011

- Gerald Herbert

Former Gov. Edwin W. Edwards, who embodied Louisiana’s populist era in the late 20th century — championing the poor and ushering Black people and women into state government but also facing repeated accusations of corruption before finally being sent to prison for taking bribes — died Monday at his home in Gonzales.

He was 93.

The cause of death: respiratory problems that had plagued him in recent years, said Leo Honeycutt, his biographer. Friends and family surrounded his bedside.

A Democrat, Edwards dominated the state’s politics for 25 years and even enjoyed a brief and spectacular turn in the national spotlight during the 1991 governor’s race when he faced off against former Ku Klux Klan grand wizard David Duke, a Republican. Edwards won 1,057,031 votes, the most ever in a Louisiana gubernatorial election.

With his bayou charm, razor-sharp mind and quick wit, Edwards personified the state's "Let the Good Times Roll" motto, proudly proclaimed himself as the first Cajun governor in the 20th century and, by defeating Duke, became the only person elected to lead Louisiana four times and serve 16 years.

“He was extremely intelligent, and he was able to analyze problems and find solutions where other people couldn’t find them,” said former U.S. Sen. John Breaux, who was his assistant when Edwards was in Congress and succeeded him as Louisiana’s 7th House District representative. “I think he had a very big heart and a good feel for people who were less advantaged than he was.”

But many of his achievements — including the modern state constitution that has served Louisiana since 1974 — were overshadowed by the fallout from his catch-me-if-you-can philosophy that ended with him getting caught and serving 8½ years in prison.

Edwards was released in 2011 and, true to reputation, promptly married his third wife, Trina — she was half a century younger — and moved to Gonzales. In 2013, he fathered a son with Trina, named Eli. Edwards already had four adult children with his first wife, Elaine, and they were old enough to be Eli’s grandparents.

Later, while continuing to proclaim his innocence, Edwards said being sent away was a blessing in disguise.

“I wasn’t glad I went to prison,” he said during a 2018 interview. “But I figure that meeting (Trina) and having Eli as a child more than compensates for the unfairness and the agony of being there.”

The stain of political corruption typically sinks a politician's reputation, but Edwards enjoyed renewed popularity in the years after his release.

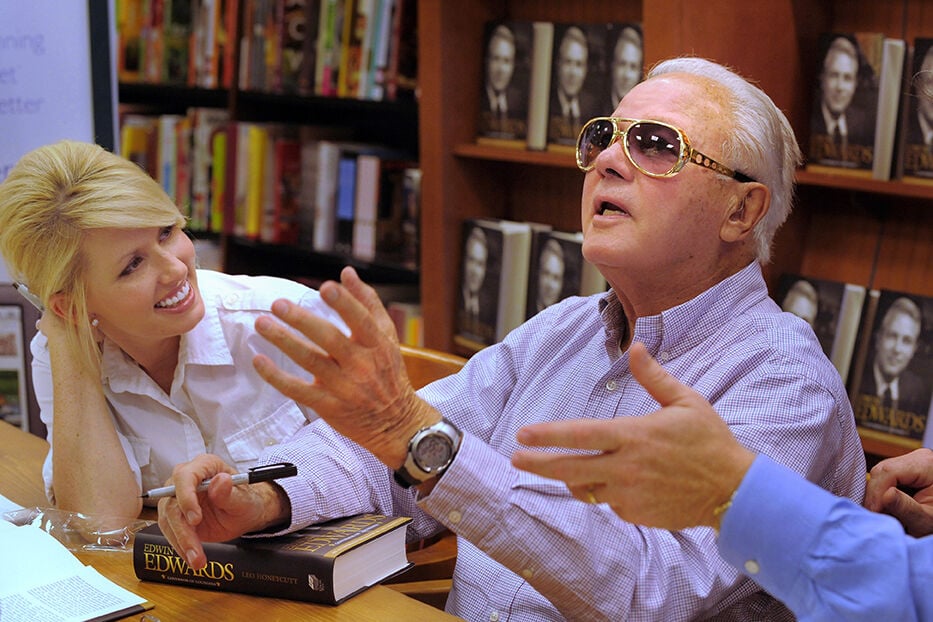

Political clubs, chambers of commerce and other groups invited him to speak. His authorized biography became a bestseller in Louisiana.

In 2017, his 90th birthday bash at the Renaissance Hotel in Baton Rouge filled a ballroom with some 500 guests paying $250 per person. Gov. John Bel Edwards, who is not related, and former Gov. Kathleen Blanco were among the attendees.

"I'm 90 years old and I woke up Friday and took my son to preschool," Edwards told the crowd to uproarious laughter.

Edwards' revival even struck Jim Letten, who led the team of federal prosecutors that convicted Edwards in 2000 and later, as a U.S. attorney, repeatedly dismissed calls for leniency from Republicans and Democrats alike.

When Letten ran into Edwards at a New Orleans Saints game in 2014, the former governor reached out his hand, and the prosecutor shook it. “I’ve got to tell you this, governor,” Letten blurted out. “You look amazing. It’s unbelievable.”

Later, Letten said, "Nobody can not agree that he’s not a resilient person.”

Edwards is the fourth former governor to die within the past two years. The others were Blanco, Mike Foster and Buddy Roemer.

Throughout his career, Edwards won fervent support from poor White people and Black people — and grudging respect from his political rivals.

“He was the most effective, skilled, wily politician I ever knew,” Roemer once said of Edwards.

But the question for history is whether he employed those formidable skills to benefit the public or his pocketbook. Although he could point to notable achievements over his 16 years in office, when he left the Governor's Mansion for the final time in 1996, Louisiana remained among the least educated, poorest and least healthy states in the country. Beginning in the 1970s, Edwards opened the state to massive chemical waste dumping to benefit political supporters, and Louisiana continues to live with that legacy.

"He knew how to use power as well as anybody we’ve ever seen, perhaps since Huey P. Long," said Bob Mann, a former congressional and gubernatorial aide who teaches at LSU's Manship School of Mass Communication. "If he had been honest, who knows how far he and the state could have gone?”

Raised during his early years in an unpainted farmhouse in central Louisiana that had neither electricity nor running water, Edwin Washington Edwards was the latter-day heir of the populist era led by the Long brothers — first Huey P. and then Earl — in the years before and after World War II.

Low-key beginnings

In 1954, Edwards got his start in politics when he was elected to the Crowley City Council; he won reelection two more times. In 1964, he defeated an incumbent to win a seat in the state Senate. In 1965, he won a special election to Congress and set his sights on achieving his lifelong goal: being elected governor.

One of 17 Democrats who vied to succeed Gov. John McKeithen, Edwards led the party primary, narrowly defeated then-state Sen. J. Bennett Johnston in the Democratic runoff (both elections were in late 1971) and then defeated David Treen, the Republican candidate, in February 1972.

Edwards was elected governor by forging a coalition of working-class White people — especially Cajuns in his home base — and Black people beginning to flex their electoral muscles. Over the next four years, he oversaw the passage of a number of highly regarded reforms sought by good-government groups. None were greater than the 1974 constitution, which simplified the operation of government, including allowing local governments to make substantive changes without having to win the Legislature’s approval.

Edwards easily won reelection in 1975. Because of term limits, he had to sit out the 1979 campaign won by Treen, who became the state’s first Republican governor since Reconstruction. Edwards overwhelmed Treen in 1983 to win a third term but lost his reelection bid in 1987 after the oil bust ruined the state’s economy.

Edwards made a comeback in 1991 to win a fourth and final term, routing Duke in the runoff election. In 1994, Edwards announced he would not seek reelection, just after marrying his second wife, Candy Picou, a 29-year-old nurse.

In 1997, a year after Edwards left office, news broke that he was under federal investigation, accused of having accepted payoffs from companies seeking a state license to operate riverboat casinos. He was convicted on 17 counts in 2000 and entered federal prison in Fort Worth, Texas, two years later.

In his later years, Edwards would say his greatest political achievements were passage of the 1974 constitution and getting the Legislature to begin taxing oil production based on the market price rather than a flat fee. When oil prices soared in the 1970s, Edwards had plenty of extra money to spend on new roads, bridges, ports, hospitals and schools.

Like Huey P. Long, Edwards throughout his political career urged the state to take care of the underprivileged. And like Long, he cut deals to steer work to favored businessmen, who provided the money he needed to run his campaigns. And also like Long, he faced repeated accusations that he pocketed some of the money.

Whereas Long typically crushed critics with brute political force, Edwards used humor to disarm them. Asked about accepting illegal campaign contributions, Edwards said, “It was illegal for them to give but not for me to receive.”

When news broke in the mid-1970s that South Korean influence peddler Tongsun Park had given his $10,000 to Edwards' first wife, Elaine, Edwards said she had never told him.

Edwards suffered no political backlash when a former top aide, Clyde Vidrine, published a tell-all book in 1977 called “Just Takin’ Orders.” In it, Vidrine told salacious tales of his boss’ extramarital affairs and his frequent gambling trips to Las Vegas.

Edwards didn’t turn defensive when asked about his Las Vegas junkets. He invited a reporter once to accompany him for three days, saying he enjoyed the camaraderie of gambling with friends and never gambled more than he could afford to lose.

“I think people realize that public officials are human and that we have our faults, our inadequacies,” he said once, “and if we don’t try to be hypocritical or sanctimonious about it, I think they’ll forgive us for it.”

In 1980, just after stepping down as governor, Edwards served a day as an associate justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court. That led him to crow that he was the only person in the U.S. who had served as governor of his state, as a member of the U.S. Congress and as a member of his state's highest court.

Treen, honest and fair but an unwilling deal-maker, was no match when Edwards ran against him in 1983. Treen, Edwards said in a devastating comment, was “so slow it takes him an hour and a half to watch ’60 Minutes.’”

It was during that campaign that he delivered perhaps his most famous line. He uttered it to Dean Baquet, then a young Times-Picayune reporter and now executive editor of The New York Times.

Edwards couldn’t lose the election, he told Baquet, unless he was caught “in bed with a dead girl or a live boy.”

He was right. Voters returned him to the Governor’s Mansion with a 63% to 37% margin. The 1,002,798 votes he received marked the first time a Louisiana governor received more than 1 million votes.

Edwards didn’t even wait for his inauguration to mark a return to the heady days of his first two terms. To help retire a $4 million campaign debt, he filled two 747s with 600 supporters, at $10,000 a head, for a weeklong trip to France and Monaco. Edwards won $15,000 playing craps in Monte Carlo and then told the dealer: “Give me a wheelbarrow for my money.”

But when Edwards moved back into the Governor’s Mansion in early 1984, oil prices were dropping, and so were state tax revenues. Edwards pushed a $730 million tax increase through the state Legislature, but it did not plug the budget gap, and it antagonized voters. Louisianans stopped chortling at his antics. The hayride was over.

So was his ability to stay one step ahead of the federal authorities, who by then had convened more than a dozen grand juries to investigate him.

The scoop on state politics in your inbox

Edwards was indicted in 1985 and charged with receiving $1.9 million in payoffs from hospitals and using at least some of the money to pay gambling debts. During the trial, an executive from Caesars Palace testified that he had flown to Baton Rouge to collect $400,000 on one trip, $380,000 on another — in suitcases stuffed with cash.

The first trial ended in a hung jury. A second trial resulted in his acquittal.

Afterward, a reporter asked him, “What’s your answer to those who will say, ‘Edwin Edwards is guilty as hell, but the prosecution just wasn’t smart enough to get him?’”

“They’re half right,” he replied.

Reversals of fortune

The trial’s revelations and the sour economy took their toll on Edwards’ popularity. He faced four strong opponents in 1987. The favorite was a candidate nicknamed ABE, as in Anybody But Edwards. Roemer, then a congressman overtook them all as voters responded to his promise to repudiate the Edwards era and “slay the dragon,” as Roemer put it. He led Edwards in the primary. That night, Edwards conceded the runoff election. It was his first election defeat.

But as governor, Roemer ran into trouble, in part because Edwards worked behind the scenes with state legislators to block his initiatives. In 1991, Edwards sought to avenge the defeat and ran for governor again. By then, Duke was cleverly tapping into Whites’ racism and anger with the state’s high unemployment rate.

Edwards ran first in the primary, followed by Duke, a Republican state legislator from Metairie who delivered a race-based message against political elites. The runoff election became front-page news across the country because of Duke’s Klan past.

In a debate two weeks before election day, Edwards delivered a powerful closing statement that marked their sharp differences.

“While David Duke was burning crosses and scaring people, I was building hospitals to heal them,” he told a statewide televised audience. “When he was parading around in a Nazi uniform to intimidate our citizens, I was in a National Guard uniform bringing relief to flood and hurricane victims. When he was selling Nazi hate literature as late as 1989 in his legislative office, I was providing free textbooks for the children of this state.”

Two bumper stickers captured the ambivalence that Edwards generated. “Vote for the Crook. It’s Important,” read one. “Vote for the Lizard, not the Wizard,” read another.

Edwards trounced Duke with 61% of the vote.

Edwards had won over skeptics — including two former foes, Roemer and Treen — by promising to avoid becoming embroiled in scandal. He didn’t keep the promise.

During the campaign, Edwards pinned revitalizing the state’s economy on the creation of a single land-based casino in New Orleans. It would create 25,000 jobs and generate millions of dollars in tax revenue, he promised.

In 1992, the Legislature legalized the New Orleans casino following a controversial vote in the state House overseen by Speaker John Alario, Edwards’ close ally. Licensing the casino — as well as 15 riverboat casinos approved under Roemer — provided Edwards with a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for skullduggery. He did not miss a chance to cash in.

Newspapers reported repeated instances in which Edwards strong-armed state regulators to benefit his friends. His children set up businesses to grab a share of the new riches. Meanwhile, problems delayed the opening of the New Orleans casino.

Voters turned on Edwards. Close supporters noticed that he seemed to enjoy the job less than before, especially after he fell off a horse and broke his back. In June 1994, Edwards made the surprise announcement that he would not seek a fifth term the following year.

The luck runs out

After he left office in January 1996, federal authorities were soon investigating him again, this time on accusations that he had taken payoffs from men wanting licenses to operate the riverboats.

The FBI bugged his Baton Rouge law office, and several associates — including Eddie DeBartolo Jr., the owner of the San Francisco 49ers football team — pleaded guilty to engaging in bribery schemes with the former governor.

The federal trial in Baton Rouge began in 2000. Three months later, an 11-person jury found him guilty on 17 of 26 counts of extorting riverboat owners and money laundering in hiding payoffs from casino owner Robert Guidry. Four other defendants were also found guilty, including Edwards’ son Stephen.

“The Chinese have a saying that if you sit by the river long enough,” Edwards told reporters moments after the jury’s verdict, “the dead body of your enemy will come floating down the river. I suppose the feds sat by the river long enough, so here comes my body.”

Edwards was acquitted in a fourth criminal trial, centering on allegations he gave favorable treatment to a failed insurance company.

Two years later, about to enter federal prison having exhausted his appeals, the 75-year-old Edwards had lunch with attorney Lewis Unglesby. After they said their goodbyes, Unglesby thought his friend would never survive his prison sentence.

Over the next eight years, Edwards divorced his second wife, Candy, served as the chief librarian during his two years at Oakdale Federal Correctional Institute and helped other inmates study for the GED.

While at Oakdale, Trina Grimes Scott, who lived in Alexandria, sent him a fan letter. Edwards was receiving so much mail that she received a form letter in return. She wrote him again, and this time she enclosed a photo. Intrigued, he invited her to visit, and they spent the entire day talking. She began visiting him regularly.

Edwards not only proved Unglesby wrong, but he thrived once he was released from prison.

Men clapped him on the back and women asked him for a kiss. And he had his younger bride on his arm.

Edwards’ authorized biography, a collaboration while in prison with former television morning show anchor Leo Honeycutt, became a bestseller in Louisiana. He and Trina briefly starred in a reality TV show.

To remain in the public’s eye, Edwards ran for Congress in 2014. He received 38% of the vote and lost to Garret Graves in a district designed to elect a Republican.

On election night, Edwards climbed onto a raised stage in a hotel meeting room, Eli in his arms, Trina by his side. As he waited for supporters to crowd in, Edwards lightly sang, “The party’s over. It’s time to turn out the lights.”

None of his four adult children with Elaine sought political office. But he would say later that Trina had printed a T-shirt that read “EWE 2053” — for Eli Wallace Edwards, who would be 40 that year.

Edwards was born on Aug. 7, 1927, in Johnson, a community outside of Marksville in Avoyelles Parish. His father, Clarence, a Presbyterian, had only a third-grade education. His mother, Agnes, a Catholic, had left school after seventh grade.

Clarence Edwards eked out a living as a sharecropper, raising chickens, ducks, geese, pigs, cows and sheep. Agnes Brouillette Edwards was a midwife who taught her five children to speak Cajun French. Edwin was the middle child. Although reporters described him as Cajun, who descended from Canada, his mother’s forebears actually were from France.

Young Edwin began his schooling in a one-room schoolhouse where one teacher taught grades one through four. As a teenager, he planned to be a preacher, practically memorized the Bible and preached in Marksville's Church of the Nazarene.

During the five years of interviews Honeycutt conducted for the biography while Edwards was in prison, he said the former governor described the effect of growing up with so little money: “Poverty will make you bitter or better. You get mad at the world because you’re poor, but you realize that it will take work and education to get what you want. You can’t focus on what you don’t have; you focus on what you want.

“In that sense," Edwards continued, according to Honeycutt, "poverty is a blessing because life is a problem from the get-go. You learn to problem-solve from the beginning.”

Edwards trained to be a Navy pilot late in World War II, obtained a law degree from LSU and then, in 1949, married his high school sweetheart, Elaine Schwartzenburg. Edwards and Elaine moved to Crowley, where his sister Audrey lived. He and Elaine had four children: Anna, Stephen, Victoria and David. They all survive him.

Edwards had 12 grandchildren and 19 great-grandchildren with Elaine Edwards.

Elaine died in 2018. His three brothers and his sister also died before him.

Edwards outlived four of his successors: Treen, Roemer, Blanco and Mike Foster.

Arrangements are still being finalized. He will be buried at Resthaven Gardens of Memory in south Baton Rouge.

Edwards explained his philosophy in a 1983 interview.

“In life, politics and hunting,” he said, “I play by the rules, but I take all the advantages the rules allow."

John Pope and Advocate library manager Judy Jumonville contributed to this article.

No comments:

Post a Comment