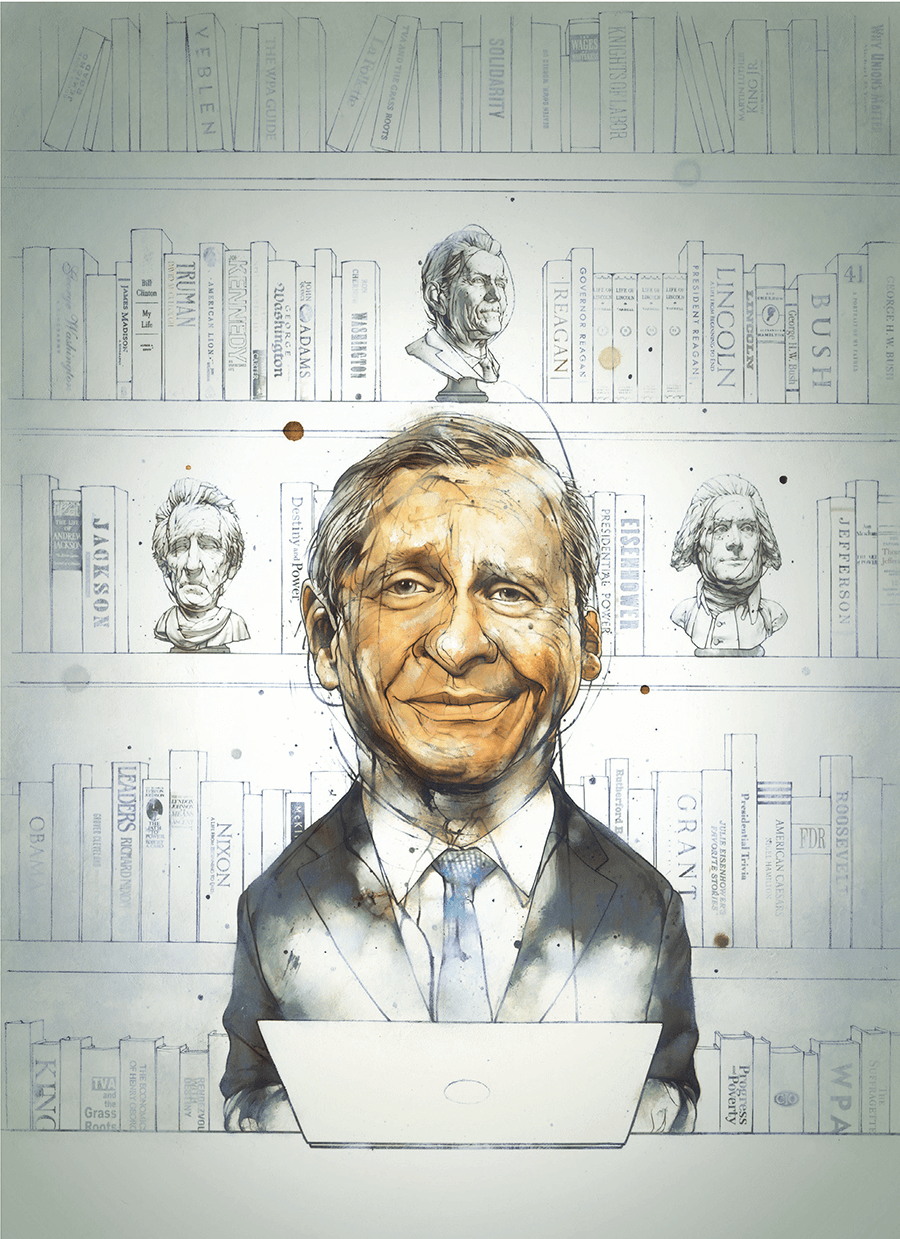

Illustration by Andrew Zbihlyj

Discussed in this essay:

The Soul of America: The Battle for Our Better Angels, by Jon Meacham.

Random House. 416 pages. $20.

The Soul of America, directed by KD Davison. HBO, 2020. 77 minutes.

It’s the beginning of the new HBO documentary based on the work of the celebrated historian Jon Meacham, and here he comes ambling through his tastefully decorated home. We glimpse autographed photos, toby jugs, old prints, comforting Americana. The prize-winning biographer of Jefferson and Jackson slowly makes his way to a TV studio in the basement, where he looks at the camera and strikes a contemplative pose.

The voice of a TV host can be heard: “Joining me now, NBC News contributor and historian Jon Meacham. Give me a history lesson.”

“It’s a complicated and fraught history,” we hear Meacham reply.

The wise-man act is a familiar role for Meacham these days. During the Trump years, he appeared on MSNBC some five hundred times, doling out lessons in pastness to an audience of anxious liberals. In the same period, he produced a dizzying number of essays, podcasts, and books, including his 2018 opus, The Soul of America. Generally speaking, Meacham has played his appointed part well, descanting with deliberation before a public that craved confirmation of Donald Trump’s record-breaking churlishness and, at the same time, assurance that everything was going to be okay—an act that was complicated and sometimes even fraught.

What deserves more scrutiny amid this blizzard of commentary is the historian’s other role, as a maker of history in his own right—specifically, as a friend and informal adviser to President Joe Biden.

I say this, and yet the relationship between the two men has never been a secret. Biden openly swiped Meacham’s book title for his campaign last year, calling on voters again and again to rescue the country’s soul from Trumpism. In October, the Democratic candidate sent a bus around the country marked battle for the soul of the nation; in both his victory speech and his inaugural address, he declared that soul restoration was to be the number one priority of his administration. Biden even interviewed Meacham—reversing the usual relationship between historian and politician—at a University of Delaware event back in 2019. Meacham, for his part, endorsed Biden last summer in a talk at the Democratic convention, explaining his concept of “the soul of America” to a prime-time audience.

We also know that Meacham helped to write a number of Biden’s speeches, including one that he then proceeded to praise as a commentator on MSNBC—a minor conflict of interest that ruffled some feathers at the network. And his influence is ongoing: a few months ago, Meacham reportedly assembled a panel of historians to meet with the president at the White House, where (one presumes) they offered their collective sagacity on the challenges of the day.

He is the intellectual of the moment, this soft-spoken biographer of great men. Meacham whispers in the president’s ear and appears on TV constantly. His books are bestsellers, they win prizes, they are endorsed by Oprah, but his ideas are not widely analyzed. Apart from a recent essay in Mother Jones, I was able to find few discussions of Meacham’s contributions to Democratic Party thinking or even to the discipline of history. What does it tell us about Biden-era liberalism that this is one of its defining voices?

Ordinarily, I would not consider Meacham a liberal at all. He is, for starters, virtually a worshipper of Ronald Reagan, whom he eulogized at length and with embarrassing sentimentality in Newsweek in 2004. George H. W. Bush, the subject of an admiring 880-page biography Meacham published in 2015, seems to rank only slightly lower in his estimation. In 2018, Meacham spoke affectionately at Bush’s funeral.

As for Meacham’s journalistic output, in the Aughts, he helped to popularize the fatuous notion that America is a naturally “center-right” nation where “radical change” is contrary to our nature. During the 2009 global financial crisis, he wrote a cover story for Newsweek describing the bank bailouts engineered by George W. Bush as an act of “socialism”—a deliberate confusion of right and left that found an immediate audience with Tea Party types.

Come to think of it, there’s something Tea Partyish about the whole genre of presidential history, the category into which most of Meacham’s literary output falls. Think of what this species of scholarship entails: the near-worship of the Founding Fathers, the focus on great men to the exclusion of most other historical factors, the fetishizing of trivial historical details (such as how many times Dwight Eisenhower cried in public, a question Meacham discussed with another presidential historian on MSNBC last year). It cannot be a coincidence that these were also the basic ingredients of the famous right-wing uprising of a decade ago, with its snake flags, its call-and-response quotation of the founders, its sappy salutes to the great presidents delivered by people such as the Fox News personality Glenn Beck, who stood at the foot of the Lincoln Memorial one day in 2010 and urged his fans to restore the virtues of those heroic personages in this fallen age of the interloper Obama.

All through the years of the liberal, white-collar “resistance,” Meacham did basically the same thing, with the script only slightly altered. As the news cycle became dominated by the interloper Trump and by Trump only, presidential history became the only history that mattered. Here, Meacham the historian would intone, is how Trump resembles Richard Nixon or Andrew Johnson. Here is how Trump fails to live up to the high standards of dignity set by FDR or Abraham Lincoln. And here is how Trump is just off-the-charts the worst president who has ever walked the halls of the White House.

What turned Meacham into the Age of Trump’s superstar historian was yoking this catastrophizing to some observation that things have been bad in America before and we have lived through them: the rise of the Klan, the Oklahoma City bombing, the downfall of Nixon. Temperament, rhetoric, decency, character—Meacham told us why these things mattered and what it would cost us to have a president who flouted them.

The historian pulled it all together in The Soul of America, an account of the country’s long wrestling match with intolerance. Here was the presidential-history formula for difficult moral times: Maybe America’s leaders weren’t so awesome after all, Meacham admitted. Maybe America wasn’t such a decent country, either. Yes, it had good impulses—but it also had bad ones, and sometimes the bad ones got the upper hand.

It’s a weighty concept, this soul stuff. Here is how Meacham explained it in the documentary last year: “The soul of the country is, in fact, this essence, which is not all good or all bad. You have your better angels fighting against your worst impulses. And that has a religious component, certainly. It’s also, though, a matter of historical observation.”

So: There is Good in America, Meacham tells us, and there is also Bad. These are history’s diagnostic categories. People in the past have done fine things, and they have done wicked things. As the book’s subtitle puts it, our history is an unending “battle for our better angels,” a theory the historian borrowed from a speech by Lincoln.*

It’s the dialectic of history, imagined for a new Manichaean generation: things that are Good exist in eternal conflict with things that are Bad. The imperative facing intellectuals, meanwhile, is to inform us that Good things are Good. And also: to proclaim to the world that Bad things are Bad.

Perhaps you think defining these categories would be difficult. No. Defining these categories is a snap. Bad things are the things that everyone already knows to be bad, such as slavery, bigotry, and isolationism. Good things are, similarly, the things whose goodness is well known, such as women’s suffrage and the civil-rights movement. In The Soul of America, Meacham urges us to disapprove of the Ku Klux Klan, to understand that George Wallace was not a good person, and to realize that Joe McCarthy was a dishonest individual. The quotes Meacham deploys to establish these totally standard aperçus usually turn out also to be the standard ones, the ones you would find in Familiar Quotations on High-Minded Themes, if such a book existed: a famous aphorism uttered by a beloved president; the words Edward R. Murrow used to humiliate McCarthy; the clever quotation you remember hearing in a Ken Burns documentary. These are the oft-told tales of American liberalism, told here yet again.

Meacham’s long riffle through the files of the totally familiar is not without some interesting findings. One is his curious conception of American presidents as natural allies of the things that are Good, as he hands down example after example of presidents doing heroic deeds. The office, he tells us, has a power for democratic goodness that is almost magical: he calls it “the mysterious dynamic between the presidency and the people at large” without which “no understanding of American life and politics is possible.” He nails down this mystical point by stringing together one quotation after another in which presidents themselves talk about the majestic office of the presidency.

If Meacham can be said to hold a theory of American history, it is that political progress is a story of popular movements and benevolent intervention by national leaders whose souls have been upgraded by their promotion to the White House. This is how both Harry S. Truman and Lyndon Johnson are said to have come around on civil rights. Even awful presidents such as Warren Harding can be made to fit into this narrative—Meacham digs up a speech Harding gave in 1921 and then asserts that “the presidency also played a role in suggesting that America should be above Klan-like extremism.” Indeed, The Soul of America is little more than a procession of presidential anecdotes, with an occasional digression in which some eminence is quoted on the office of the presidency, before it’s back to presidents doing picturesque deeds and presidents drawing lessons from the careers of other presidents.

It is more than a little surprising that enlightened modern-day liberals, who have supposedly declared war on every inherited cultural assumption, would celebrate this obvious revival of the great man theory of history. But it also makes sense, after a fashion. For one thing, a great man theory can also be a great villain theory, with you-know-who in the starring role. Furthermore, the idea that the country’s most powerful figure experiences a gravitational pull to “the side of the angels” (as Meacham says regarding Woodrow Wilson) is a notion that appeals to the righteous mind of our time. Political virtue, we now know, is something that flows from the top down. The prosperous, the well-graduated, the woke CEOs, the tasteful people celebrated by Vogue and NPR—these are the natural allies of the Good. They make mistakes here and there (Meacham is careful to acknowledge the racist failings of his characters), but in general, we now believe that such figures make up the armies of progress. In our modern understanding, power doesn’t corrupt; it ennobles.

With its sweeping clash of better angels and wicked forces, TheSoul of America is a new take on an old historical favorite, a story of Progress in which reformers square off against reactionaries. Reading Meacham’s version of this well-known narrative made me think of one of the classics of the genre, Eric F. Goldman’s 1952 history of liberalism, Rendezvous with Destiny. The two authors have much in common: in addition to telling the same stories, both of them emphasize the deeds of progressive presidents and take their titles from famous presidential speeches. Like Meacham, Goldman used to appear frequently on TV; he even served as an adviser to Lyndon Johnson.

The main elements of Meacham’s tale all appear in Goldman’s earlier account: the struggle against racism, the fight for women’s suffrage, the danger of red scares, and so on. But the bulk of Goldman’s 1952 volume is concerned with something else, something that is almost completely missing from Meacham’s book: I refer to the problems of capitalism—how farmers and workers learned to organize themselves and exert influence over the economic system. This story was well known to liberals in 1952, and Goldman ranged over the familiar epic with writerly swagger: Populism, progressivism, the Knights of Labor; Henry George, Thorstein Veblen, Robert La Follette; and all of it leading up to the landmark achievements of the Thirties—the Tennessee Valley Authority, the Fair Labor Standards Act, the growing power of unions, and so on. It is not an exaggeration to say that these things were what people used to think liberalism was about, at least in part.

Today they have all but disappeared. With the exception of progressivism, none of the things I just mentioned are described in The Soul of America. Meacham throws the word “populist” around, of course, but always as a pejorative, as a synonym for “demagogue” or “racist,” never once in connection with the actual movement—the agricultural uprising of the 1890s that historians like Goldman understood as an early battle in the long war for American economic reform.

Working-class movements in general get short shrift from Meacham. He rarely mentions trade unions in The Soul of America, and only includes famous labor leaders when they appear in some other field—Eugene Debs because he was imprisoned for a speech, A. Philip Randolph because he proposed a march on Washington for civil rights. The Ku Klux Klan of the Twenties, by contrast, plays a huge role in Meacham’s story, and is described as an organization that sought to court “white working-class voters” and provide an answer to their fears of unemployment and their dreams of infrastructure spending and better health care. The Klan only disappeared, Meacham sighs with relief, because of the booming economy.

Economic discontent is the recurring villain of Meacham’s history. The grievances of the poor and the working class are always depicted as disreputable in some way, leading either to racism or to Huey Long–style demagoguery. The introduction to The Soul of America begins with an epigraph that attributes racism to economic anxiety; by page five, Meacham has attributed Trumpism (in part) to the arrival of “an economy that prizes Information Age brains over manufacturing brawn.” In the HBO documentary, Meacham explains Trump’s win in 2016 with two numbers:

One is seventeen percent. That’s the percentage of Americans who say they have trust in the federal government. . . . The other’s $130,000. That’s the number that some economists believe a family of four needs in annual household income to lead what they would think of as a classic, post–World War II middle-class life. Annual income for a family of four is about $56,000 right now. So in that missing income gap, and in that trust gap, you have the ingredients for a kind of populist moment like this, where someone says, “those people are to blame for the fact that you don’t have this money.”

Economic troubles led directly to Trumpism, to racism, to fascism. That’s what “populist moments” are. And the answer to the problem, which Meacham gives in the documentary, is to fill the crucial office of the presidency with fine gentlemen like Franklin Roosevelt, leaders who “don’t cater to it, who tamp it down instead of flame it.”

On the surface, this sounds like what our modern-day opinion cartel calls the economic anxiety thesis: the much-denounced and now unacceptable belief that what motivated Trump voters was their declining fortunes, rather than racism. What saves Meacham from heresy is that he seems to see the two factors as more or less identical. In his understanding, economic insecurity naturally propels the (white) lower orders to racism. It’s not hard times or bigotry; it’s both. They are pretty much the same.

Presidential history is often criticized for producing no original interpretations, but let’s give Meacham credit for this: his treatment of economic discontent represents something new and radical. That there is a connection between economic distress and Klan-style demagoguery is well known, of course. But scholars have traditionally believed that there are also connections between crisis and reform, between crisis and revolution. That, after all, is the story of 1789, of 1848, of 1917, of the Roosevelt Administration, and so on, right up to 2008, when Barack Obama was elected president during the global financial crisis. Economic disaster brings upheaval, accountability, reform: Karl Marx believed it, Eric Goldman believed it, Glenn Beck believed it, the business community used to believe it, everyone believed it. Indeed, this is why the left exists in every country on earth.

Except for ours. In America, where the party of the left now prides itself on representing (as Hillary Clinton once put it) “the places that are optimistic, diverse, dynamic, moving forward” and that produce the bulk of the nation’s economic output, we have a different theory, courtesy of our most influential historical thinker: hard times are dangerous times for the side of the angels.

The obvious test for such a theory is, of course, the Great Depression, when capitalism broke down and liberalism scored some of its greatest achievements. How does Meacham interpret that era, given his revisionist understanding of economic discontent?

One thing he does is to suggest, ever so subtly, that maybe it’s the victims themselves who were to blame. In 2019, Meacham co-wrote a book with the country music star Tim McGraw about American music, specifically about songs of “patriotism” and “protest.” When he gets to the Thirties, Meacham chooses the unemployment anthem “Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?” as a representative number. The book includes a vintage advertisement as an illustration for that mournful story. The text in the antique ad is easy to read:

the bread line

There are periods of depression and periods of prosperity. But unfortunately there is always a bread line for those who haven’t learned to save. During prosperity you must save if you are to bridge the periods of depression.

Another innovative move the historian makes is to downplay the capitalist-failure aspect of the disaster. In the HBO adaptation, Meacham describes the Depression as a time when “we were paying the price for isolationism, paying the price for instituting immigration quotas, putting up high tariffs.”

Blaming the Depression on high tariffs is a familiar talking point among free-market editorial writers, but blaming it on immigration quotas? That’s one I’d never heard before. I asked Robert McElvaine, a well-known historian of the Depression, and he, too, was stumped: “I have never heard the slightest hint of such an argument. Indeed, I don’t see how it could make any sense.”

Other landmarks of the era disappear in the Manichaean haze. As the documentary continues, images of violent clashes from the 1934 Teamsters strike in Minneapolis start flickering across the screen. This is an episode that other historians of liberalism (such as Irving Bernstein, author of the 1969 labor-history classic The Turbulent Years) endow with tremendous significance, seeing it as one of the moments when workers started taking matters into their own hands. Here is Meacham’s voice-over: “There were riots in the Midwest.”

We don’t learn any more than that. One Depression-era group that does matter to Meacham, however, is the Nazi-affiliated German-American Bund, whose members are shown marching in the street and listening to their leader’s snarlings in 1939. Meacham doesn’t really tell us why the Bund was important. He merely marvels at its existence, leaving us to suppose that it represented yet another bad day for the troubled American soul.

Describing the Depression in this way has a predictable result, and it is to make Franklin Roosevelt into another revered president-hero who resisted extremists and “rescued capitalism” while saving civility and democracy. As Meacham puts it in the documentary, FDR may have understood that Americans were desperate, but he also knew that you “don’t cater to it.”

It is true that FDR often tried to reassure people. But it would be inaccurate to say that he didn’t “cater to it,” if by “cater to it” one means “acknowledge the people’s economic anxiety” or “steer their outrage in the right direction.” Roosevelt did things like that all the time; it’s why he was elected in the first place. Just glance at FDR’s combative 1936 State of the Union address, in which he declared that he had “earned the hatred of entrenched greed” and that the country’s business elite was planning its return to power: “Autocrats in smaller things, they seek autocracy in bigger things.”

Those remarks call to mind an important truth about the Depression years and the broader history of reform. FDR’s most dangerous enemies weren’t five-and-dime führers playing Nazi in homemade uniforms; they were the wealthiest people in the land. They were America’s great industrialists, its leading lawyers and economists, the publishers of its newspapers. These were the men who dabbled in fascism and hired strikebreakers and believed in scientific racism. And many of these fine, affluent, tasteful people came together in the mid-Thirties as the American Liberty League, the great-granddaddy of all the right-wing front groups to come. (Meacham never mentions it.) Roosevelt fought against them not by respecting norms or by refusing high-mindedly to cater to people’s economic fears; he did the opposite, and in 1936 he trounced what he called “organized money” in one of the greatest victories for liberalism of all times.

Liberals only rarely talk like FDR anymore. Indeed, the situation that confronted him is almost precisely reversed: it is liberals who have brought the ruling class of America together in recent years; it is liberals who identify their fortunes with elite consensus; it is liberals who bridle at theories of economic anxiety; and it is liberals who regard the white working class as fundamentally irrational, if not reactionary.

Perhaps expressing this consensus in his elegant style is what has made Meacham liberalism’s favorite historian. All the peculiar elements of the affluent, educated worldview are here: the reduction of history to a struggle between moral categories, the deletion of working-class movements from the story of progress, the distaste for economic grievance, the obsessive focus on the executive office, and the score-keeping of racist remarks, as though wickedness could be quantified and exorcised in that way.

And still the biggest question of all remains: Why is it that some moments of economic catastrophe lead to victory for the forces of liberalism while others give us reactionary demagogues like Donald Trump? Meacham himself never asks, because the worker-uprising part of the story is largely omitted from his telling.

Allow me to suggest that the answer has something to do with how liberalism understands itself in this age of Meacham. Consider the liberal thinkers who blame economic victims for their problems—telling them that they should have saved their money, or that they should have studied harder in school—even as liberal politicians make themselves into conspicuous friends of Wall Street and Silicon Valley. It doesn’t take a genius to realize that liberals of that kind will probably not see those economic victims come running back for another helping. Those victims may start to look elsewhere for a solution, and they may even choose to side with a bastard like Trump.

It is Jon Meacham, not I, who has the ear of President Biden, but if I could whisper a suggestion to the man behind the Resolute Desk, it would be this: Read a different book, Joe.

No comments:

Post a Comment