How else to explain the media and market frenzy that followed the announcement, issued at 7 a.m. on Tuesday, Jan. 30, 2018, that Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, and JPMorgan Chase—three of the nation’s largest, most high-profile, and best-run companies, then with some $534 billion in revenues between them—were teaming up to take on the ever-more-expensive, ever-more-complex problem that is American health care. Or what Berkshire CEO Warren Buffett colorfully described in that press release as “a hungry tapeworm on the American economy.”

The announcement contained both notes of humility—Buffett: “Our group does not come to this problem with answers”; Amazon chief Jeff Bezos: “The health care system is complex, and we enter into this challenge open-eyed about the degree of difficulty”—and a spirit of grand sacrifice: As JPMorgan’s Jamie Dimon put it, “Our goal is to create solutions that benefit our U.S. employees, their families, and, potentially, all Americans.”

The effort was “in its early planning stages”—a management team, headquarters, key operational details, all TBD—and it had come as a total surprise to virtually everyone, including JPMorgan’s health care bankers, who had reportedly been given a heads-up only the night before. What did it all mean, practically? No one knew for sure. Nonetheless, news of the fledgling venture seemed to many a promise of disruption to come.

Warren Buffett called the industry "a hungry tapeworm on the American economy."

“They were in many ways blasting the current configuration of the health insurance industry, in very strong terms,” says Matthew Borsch, a managing director at BMO Capital Markets. “You got the sense that they were making this revolutionary commitment to some kind of transformation to the relationship between employer groups and the health insurance carriers.”

Sure enough, the stocks of major health care companies including UnitedHealth, CVS, Cigna, and Aetna tanked. By the end of the week the S&P 500 Health Care index had fallen 4.8%. Those inside the system seemed cowed by the news: Express Scripts issued a statement more or less acknowledging it had to do better. A senior executive at Optum, the $136 billion subsidiary of UnitedHealth, the $257.5 billion insurer—which counted JPMorgan and some of the Berkshire companies as customers—later testified in court that some of his employees “were very scared this company would take over the world.”

To those who had toiled in the world of employer-sponsored health care for decades, trying but never really succeeding to come up with new ways to control costs and improve outcomes—promoting wellness activities and chronic disease management programs; investing in navigation tools and second-opinion services; embracing high-deductible health plans in an effort to make beneficiaries better, more cost-conscious users of care—the statement, from three powerful CEOs, was cause for celebration. Here was a rare show of leadership from corporate chieftains with heft and a shot across the bow at an industry (insurers, health providers, pharmacy benefit managers, or PBMs) that for too long had been allowed to profit by maintaining the miserable status quo.

The illustrious trio looked like a dream team actually capable of shaking things up in America’s bloated and entrenched $3.8 trillion health industry. Their CEOs were all visionaries in their industries. Berkshire and JPMorgan brought finance chops. Amazon had the proven playbook—a consumer-first ethos, big data, bold and patient investment—for audacious disruption. Between them, they had deep pockets, ample resources, and the purchasing power that came with their combined 1.2 million employees.

Five months in, the team announced another star would lead the venture: Atul Gawande, the surgeon and influential New Yorker writer whose clear-eyed analysis of America’s dysfunctional health care system had earned him the admiration of Barack Obama and Buffett.

Other hires were announced, but little news emerged. A legal dispute involving a former Optum employee who accepted a job at the new entity in late 2018—allegedly violating his noncompete—allowed perhaps the fullest peek behind the curtain. The court proceedings indicated that as of January 2019, the still-nameless venture had 20 employees and a plan that was extremely nebulous. (More revealing, at least in terms of how industry incumbents viewed the project, was the vigor with which Optum had gone after the ex-employee, a member of the corporate strategy team. After performing a forensic analysis of printouts and searching his office, Optum accused him of stealing trade secrets, including an unrecovered “Project Orange Fact Book.” The court case, parts of which both companies argued to keep under seal, was eventually dismissed.)

In March 2019, the venture finally got a name, Haven. The first major departure came in May; COO Jack Stoddard, an alum of Comcast (which has one of the most innovative health benefits programs in the country), stepped down eight months after joining. Many followed—the venture, once thought to have abundant resources, even laid off some people—and then Gawande, who had never left his teaching, writing, and doctoring positions, transitioned from CEO to chairman in May 2020. The project officially sputtered to an end earlier this year, when the companies released a joint 85-word statement on Haven’s website. In the end, Haven’s short life wasn’t even dignified by a corporate press release.

So, what happened with Haven? What can be learned? Readers, after months of reporting, I’m sorry to confess I can offer only a hazy, partial picture.

Gawande also declined Fortune’s invitations (over several months) to be interviewed. Ironclad nondisclosure agreements have kept other former Haven employees from speaking.

It’s a shame. I say that as a humbled journalist, but more on behalf of the dozens of people I spoke to who are struggling with the same issues Haven was tackling and were hopeful to learn from its efforts. After all, this is about how to make health care more affordable and accessible to employees.

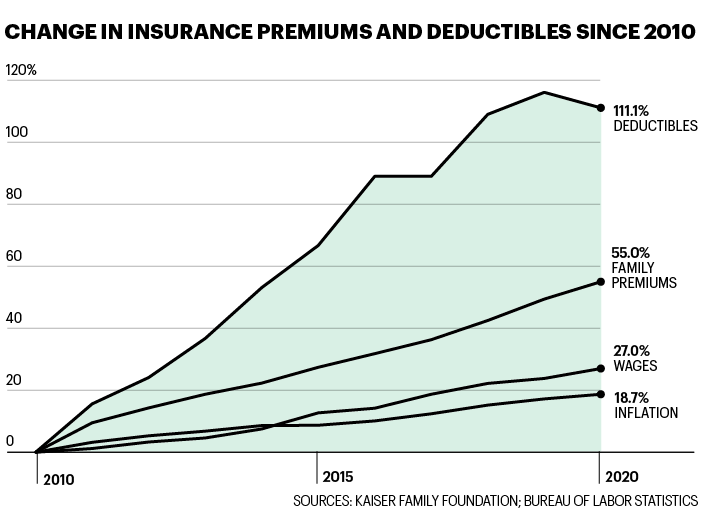

That’s no trivial matter. Roughly 160 million Americans currently get health insurance through their employers. They have been considered the lucky ones, but as Gawande noted in a recent conversation with UCSF Department of Medicine chair Robert Wachter—one of the few occasions when he’s commented publicly on Haven—for many working Americans, employer-sponsored insurance is not much of a benefit anymore. With the average annual family premium standing at $21,342 and deductibles often topping $2,000, the cost of coverage is simply too high.

The opportunity to address that problem, Gawande told Wachter, was in part what drew him to Haven. Haven’s health plan, rolled out to tens of thousands of JPMorgan beneficiaries in Ohio and Arizona, was a step toward that, he said. The plan, which he described as popular and “financially viable,” is still available to those employees today. Members have no coinsurance and no deductibles, just predictable co-pays, inexpensive mental health and primary care, and free access to 60 essential drugs. (JPM already offered the prescription benefit.)

Of course, the costs are crippling for businesses as well. Though they have recently pushed an increasing share to their workers, employers still pay most of the health care bill, one that reliably increases at a scandalous rate of 5% to 10% every year (and at an even higher rate for small businesses). That’s money firms are plowing into a health care industry—to which they pay, on average, 250% of Medicare rates—and not into wages or R&D or anything else.

Haven was hardly the first effort trying to improve this dismal state of affairs. Local, regional, and national coalitions have focused on group purchasing and value-boosting strategies. Innovations by Walmart, Boeing, and GM have been embraced as industry models. And in 2016, the Health Transformation Alliance, another effort aimed at reducing costs and improving outcomes, launched with the backing of 20 companies including Macy’s and Verizon (not to mention JPMorgan as well as Berkshire’s BNSF). The spirit in which these organizations tend to operate is open and collaborative, with a feeling that “a rising tide lifts all boats.”

Haven set out to fix health care but suffers from one of its worst traits—a lack of transparency.

Are any of those hurdles what felled Haven? My hunch, after speaking with dozens of people—experts, employers, individuals involved in similar initiatives, health system participants, and a few Haven insiders who would not speak on the record—was that it was all of them and more.

Haven always loomed larger in the imagination than it did on the ground. At its peak, it was a startup of 75-some employees, the majority of whom worked out of a coworking space in downtown Boston.

And on closer inspection, the dream team was really more of a motley crew. The three companies’ 1.2 million employees were dispersed across the country, meaning Haven didn’t have market power in any one place—the real key to driving down prices with providers.

Each company had its own approach to health benefits, with differing priorities and decision-making processes. Amazon is consumer-focused, JPMorgan more oriented around “relationships and loyalty,” says Owen Tripp, the CEO of Grand Rounds Health, a second-opinion and navigation service whose customers include the Haven companies. (He was also a candidate for the top job at Haven.) Berkshire, meanwhile, didn’t have one style, but many: Its dozens of portfolio companies, from Acme Brick to Dairy Queen to Berkshire Hathaway Energy, handle their benefits independently (allowing ample opportunity for those “dumb things”).

That meant that no matter how good Haven’s ideas, they couldn’t be easily implemented across all the companies. “It was just very different deploying at Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway, and JPMorgan Chase. There are different cities, different populations, exceedingly different cultures of organization,” Gawande told Wachter. Haven, then, wouldn’t work as a sort of benefits office. Instead, Gawande said, it risked “becoming a very expensive think tank.”

As Haven dealt with joint venture pains and dabbled in pilot projects, like building a telehealth platform for providing primary care, Amazon sped ahead with its own somewhat similar health care offerings—like Amazon Care, a sort of virtual urgent care offering that the company is now selling to employers across the country. A few people involved with Haven say this was always the plan—that Amazon would continue to work on proprietary projects—and resist the characterization reported by The Information that it caused any problems with the joint venture. Whatever the case, it’s a pretty good picture of where Amazon’s head was at.

Meanwhile, even with its star power, Haven couldn’t break the black box that is U.S. health care. The venture’s game plan had been to aggregate and analyze their shared claims data, and follow the insights to lower-cost, higher-quality care. But Haven struggled to get its intermediary partners to hand over that data. Incredible as it may sound, that’s not uncommon: Though employers are paying the bill, the insurers, PBMs, and third-party administrators that process health claims often argue they can’t share pricing information because the rates they negotiate with health providers are confidential and proprietary. Employers have little visibility into what they are actually buying as a result. It’s like going to a restaurant and being presented with a non-itemized bill, says Christopher Whaley, a policy researcher at Rand, who has partnered with employers to collect and analyze claims data from across the U.S. as part of the Employer Hospital Price Transparency Project.

“Getting data from insurance companies and PBMs is like trying to get raw meat from a caged lion,” says Robert Andrews, a former New Jersey congressman who has served as CEO of the Health Transformation Alliance since 2016. It took his group, which currently has 58 corporate members representing more than 4 million lives and $27 billion in annual spending, three and a half years—the life span of Haven and then some—to gather their collective claims data.

That points to what may have been one of Haven’s other weaknesses: its insularity. Perhaps in its bid to keep its own work secret, Haven appeared blind to—or just not interested in—valuable work that had already been done. “It was almost as if the presumption was that ‘we’re going to come up with an idea that hasn’t occurred before,’ ” says Robert Galvin, who ran health benefits for GE before becoming in 2010 the CEO of Equity Healthcare, a successful Haven-like initiative that works with Blackstone’s portfolio companies. “The reality is there are a lot of good ideas out there.” Haven reached out to Galvin looking for potential recruits, but, he says, the venture wasn’t interested when he offered to share what he had learned building Equity Healthcare. When Marilyn Bartlett, a CPA who has become something of a folk hero for the work she did as administrator of Montana’s state health plan, reached out to Haven to offer her learnings, she never heard back.

Galvin adds that this is part of a larger failing, in the way Haven was conceived and staffed. Rather than just going after new solutions, he argues, what Haven needed were people who really understood the ecosystem and “how to execute.” Some people thought the nonprofit structure was a problem; others, the glare of the spotlight. Just about everyone spoke of Gawande in glowing terms, before adding that given his lack of operational experience, he was probably wrong for the job.

Getting data from insurance companies and PBMs is like trying to get raw meat from a caged lion.

ROBERT ANDREWS, FORMER NEW JERSEY CONGRESSMAN AND CEO OF THE HEALTH TRANSFORMATION ALLIANCE

Some also wondered if relationships and conflicts of interest got in the way: JPMorgan has heaps of health care clients; Berkshire is the largest shareholder of DaVita, a highly profitable dialysis company, and owns Berkshire Hathaway Specialty Insurance, a purveyor of insurance products that cater to the health benefits market.

Other popular opinions: The founders weren’t sufficiently committed, and the mission wasn’t sufficiently clear. Haven took on too much and didn’t give it enough time. Great idea, poor execution. Most of all, health care is hard.

Haven’s founders gave up on the venture but not the goal. Amazon never stopped its work, and JPMorgan just launched Morgan Health, a new business unit that sounds a lot like Haven, but with some key modifications: Its internal team will set priorities, and the defined mission is to work with, not against, industry partners and innovators.

So, did Haven make a difference? Opinions are divided there too. Some credit Haven for sparking a conversation and spurring investment; others argue the effort undermined progress by raising the obvious question: If they couldn’t do it, who can? In a recent Kaiser Family Foundation survey of very large employers (health care companies not included), 85% of top executives think government support will be necessary to control costs and provide coverage.

Gawande goes further and has recently argued that the employer-sponsored system can’t be fixed. Noting how many Americans lost their health insurance in a global pandemic, he said to Wachter: “A job-based system is a broken system.”

Editor's Note: This story has been updated to reflect the fact that Jeff Bezos is currently CEO of Amazon. Bezos has announced that he will step down as CEO on July 5.

This article appears in the June/July 2021 issue of Fortune with the headline, "How the biggest names in business took on health care—and lost."

No comments:

Post a Comment