The battle of 1214 Dean Street commenced on a warm afternoon in early July. Angie Martinez, a 24-year-old Brooklyn native and barista, returned home to the Crown Heights rowhouse she shared with eight roommates to find her landlords, Gennaro Brooks-Church and his ex-partner, Loretta Gendville, crowding the front door with their three children, two dogs, two handymen, and a mattress. Martinez had been paying them $865 a month via Venmo for a room with one window, no heat, and no working fire alarm. The run-down four-story structure, classified as a single-family home by the City of New York, had been illegally converted and rented out by the room. In March, at the start of the coronavirus pandemic, several tenants, including Martinez, had lost their jobs, and in April, many in the house had stopped paying rent.

Now, Brooks-Church and Gendville seemed to be moving in. As Martinez approached 1214 from the street, she saw a few of her fellow tenants huddled on the steps outside. Gendville, a wiry blonde in her 40s, screamed at them, calling them squatters. Once inside, she roamed through the house, tenants say, with Brooks-Church close behind. One tenant told Gothamist that Gendville had grabbed her by the wrist as she was getting dressed in her room, ordering her to “get the fuck out.” Martinez called 911. Another tenant discovered Gendville’s two sons, ages 8 and 12, eating Popsicles in the kitchen. “It’s so nice to be home,” one of them said. When the handymen started to change the locks, several tenants decided it was better to leave, grabbing what they could and putting their belongings on the street.

After a while, the police arrived. When Martinez identified herself as a tenant, the cops said they were responding to a call from Gendville and Brooks-Church, who had also apparently dialed 911. They told Martinez that the landlords said they had nowhere else to go. Since it was their house, police said, they couldn’t make the owners leave. They told Martinez to think of the family as her new roommates. At the same time, Gendville and Brooks-Church could not legally remove the tenants on their own: Not only was a moratorium on evictions in place during the pandemic, but the law requires evictions to be carried out by a sheriff armed with a court order.

Returning to her room, Martinez discovered that her mail had been spread out on her bed next to someone’s discarded sun hat. Gendville and the kids eventually left, but Brooks-Church planted himself in the living room. “He was sitting on my chair,” Martinez says. “Just sitting there, all night.”

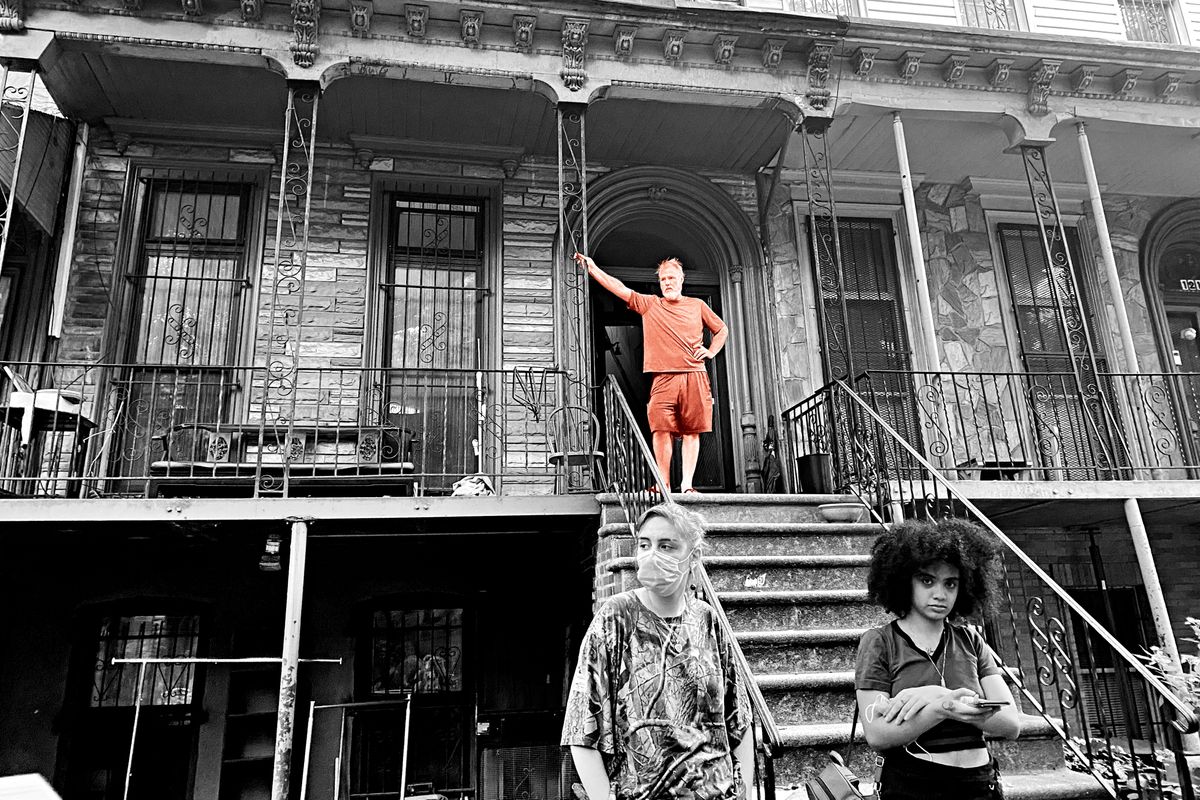

The next day, he was still there. One of the tenants contacted organizers at the anti-gentrification group Equality for Flatbush, which put out an appeal on Instagram for reinforcements. “Urgent,” it read. “Illegal Lock Out in Progress 1214 Dean Street — Go and Support Tenants Now!” By the time the sun went down, close to a hundred people, mostly young Brooklynites with their bikes, were crowded into the front yard and spilling onto the sidewalk. They chanted through their face masks at the gray-haired and -bearded Brooks-Church, dressed in a gray T-shirt and shorts, who stood, stone-faced, on the porch above. Someone beat a tambourine. At around 10 p.m., a human chain of protesters rushed the front door, and Brooks-Church, overwhelmed, fled to his SUV. Over the next two days, the occupiers held watch over 1214 Dean, sustained by donated pizza and beer.

As word of the occupation spread, it became apparent that the landlords were not just New Yorkers of considerable means. They were an ethically sourced, non-GMO, unmarried poster couple for a certain Brooklyn-specific subset of their tax bracket. Brooks-Church, 49, was a “green builder” with a construction company called Eco Brooklyn who had spoken about sustainability at the Brooklyn Public Library; he was a vocal advocate for designating the Gowanus Canal a Superfund site, making it eligible for environmental protections. He did CrossFit. Gendville, 45, was the owner of a restaurant called Planted Community Cafe and a local chain of yoga studios, spas, and children’s stores called Area — a “mini-mogul,” according to the New York Times. The pair were currently renting out a brownstone they owned on Airbnb not five miles away, with a tree house and turtle pond, for nearly $800 a night. What could drive two yogic, environmentally conscious, vegan brownstoners to kick out their unemployed tenants during a global pandemic?

“You white liberal phony fake selfish motherfucker!” a Connecticut College professor who had biked to 1214 screamed at Brooks-Church during the protest. “You belong in a Charles Dickens novel!”

He was not far off, though the landlords are more Artful Dodger than Ebenezer Scrooge. Underlying their apparent success is a tangle of questionable business and real-estate practices — some brazen, others not uncommon for entrepreneurs like Brooks-Church and Gendville, small-time prospectors mining for gold in the postrecession Wild West of Brooklyn gentrification. For those in their orbit, their public cruelty at 1214 Dean Street was not an isolated moment of madness but the inevitable culmination of years of greed and exploitation, exacerbated by the pandemic, in which even those who staked a claim in the Brooklyn boom are finding themselves unable to survive the bust. Though they own two businesses and six properties in one of the country’s most expensive real-estate markets, the landlords were apparently homeless.

“I used to call them the Brooklyn Heights Bonnie and Clyde,” says a former Area employee. “I had a Google alert set on them for just this kind of thing.”

By all accounts, Loretta Gendville is not a yogi. She did, however, predict the exact moment that two things were about to take off in Brooklyn: yoga and babies. Gendville grew up outside Chicago and moved to Williamsburg in her early 20s, trained in Swedish massage. Her first venture — funded, she said, with “small private loans” and her American Express card — was a spa in Carroll Gardens in 1998. Two years later, she opened her first yoga studio, on Smith Street, followed by her first retail store, Area Yoga & Baby, which carried maternity and workout clothes.

Gendville met Brooks-Church in an Area Yoga class, according to a person who has known the couple for more than a decade. He was “this sexy Spanish guy,” a flâneur type. He had grown up mostly on the resort island of Ibiza, the son of outlaw parents, hippies hunted by the Feds for two antiwar bombings in the ’80s until his mother turned herself in and his father reportedly got caught in Arkansas trying to pick up $6 million in cocaine. Brooks-Church became an adherent of Human Design, a pseudoscience combining astrology and chakras, which was created on Ibiza in 1992 by an advertising executive named Alan Krakower, who claimed to have received messages on the meaning of life from an entity called “the Voice.”

Brooks-Church worked as a photographer before moving to New York in 1997 to study comparative religion and creative writing at Columbia. After he and Gendville began dating, they purchased the house at 1214 Dean Street in 2002 and lived there together for a time. In 2008, they bought another old brownstone, this one in the tonier Carroll Gardens, at 22 2nd Street, for $1.4 million. There, they raised their daughter and had two sons. They had planned to refinance their mortgage to pay for a gut renovation of the house, but the global financial collapse made it impossible to get a loan. Brooks-Church was forced to renovate the house himself, and, in his telling, his eco-building business was born.

During the Great Recession, “Northwest Brooklyn” — the real-estate designation for the area that stretches from Brooklyn Heights to Park Slope — fared better than its neighbors to the east, where families of color were three times as likely to default on their mortgages. The mostly white stroller neighborhood where Gendville and Brooks-Church had invested didn’t just survive — it exploded. “Even in the dumps of a recession, as storefronts go dark in other parts of New York, the Smith Street boomlet churns on,” the Times observed. Gendville rapidly expanded her company to fit the new demographic’s needs. By 2012, she had nine Area Kids stores in the borough, along with two yoga studios, a spa, and a salon. Bloggers complained that Area’s mandala logo was the neighborhood’s Starbucks mermaid, but Gendville received accolades for her green and “aggressively local” businesses, which banned plastic bags long before the city did. In 2015, Gendville somewhat notoriously put up a Bernie Sanders poster in one of her stores a few months after Hillary Clinton had visited the location. “Hillary Clinton is, you know, more in the game with all of the corporations, which I’m against,” she told BuzzFeed. (According to public records, Gendville has not voted since 2012.)

Brooks-Church, meanwhile, fashioned himself as a kind of Brooklyn frontiersman, turning up in local-news stories for various eco-adornments he made to the 2nd Street brownstone, including a freshwater pond and a tree house. In 2011, he tried to build a literal man cave under his front yard, a project eventually shut down by the Department of Buildings. On his blog, Eco Brooklyn, he sneered at neighbors who complained about his efforts and knocked commercial developers, calling Bruce Ratner, the megadeveloper behind the Barclays Center, a “scumbag liar” who lacked “the integrity, leadership, and understanding of how Brooklyn works.” A 2013 profile of Brooks-Church in Bklynr, a local publication, reads like dreamy brownstone porn. “In the kitchen, light streamed in through floor-to-ceiling windows,” it gushes, “as his girlfriend, a baby in her arm, cooked up some eggs on a stainless steel range. Their two other children ran around the townhouse on floors made of salvaged wood.”

But the couple were scattered, chaotic bosses. Even as the eco-renovations and Area outlets proliferated, the empire seemed to operate on a shoestring. Gendville flitted between storefronts in her van; Brooks-Church would appear unannounced to make repairs at studios during class. Nearly a dozen yoga teachers, most of whom were employed as independent contractors rather than full-time staff, say that pay at Area was low and rarely on time. Teachers liked the freedom they had under an absentee Gendville to design their own classes, but some tired of having to show up at 2nd Street to ask for their checks in person. “It was just kind of a mess all the time,” says Keri Setaro, who ran yoga-teacher training at Area. Another calls Gendville “the Queen of Loopholes.” Work-study students cleaned the yoga studios, unpaid, during “karma hours” in exchange for classes, and employees did double duty as receptionists at the Area spa or wrapping gifts at Area stores. “She really thought that just because they worked for her, she owned them,” one former instructor says.

Occasionally, employees would be sent to drop something off at 1214 Dean, a linchpin in Gendville and Brooks-Church’s other business endeavor: real-estate investment. Aside from Dean Street and 2nd Street, Gendville owned a two-family home on Beadel Street in Bushwick, which she bought in 1997, and the couple added another Carroll Gardens brownstone on Douglass Street in 2005. By 2009, they owned nearly $3 million in property. For a few years, they also owned a house on Fire Island. (“I thought they were peace, love, and happiness types,” recalls a neighbor. “They were artists.”) In most of their purchases, they managed to put down just 10 percent. “We had great credit and a great track record of always paying our mortgages on time,” blogged Brooks-Church, who claimed to be a licensed real-estate broker. (No record of such an accreditation appears to exist.)

For at least a decade, while they lived at 22 2nd Street, Brooks-Church and Gendville illegally rented out Dean Street to all manner of young, upstart Brooklyn arrivals. The couple approached their landlord role in the same casual, disorderly way they approached the yoga studios. Their tenants, to some degree, didn’t entirely mind. 1214 was run like a commune: Occupants found each other on Craigslist or via word of mouth; very few, if any, signed leases; they paid their rent via apps. “We composted, we had parties, house meetings,” recalls Rachel Rosado, a former tenant who also worked for Gendville at Area. “It was special.”

But there were downsides, too. Tenants say the gas was routinely shut off when the landlords failed to pay the bill (Gendville is currently a defendant in four civil suits filed by Brooklyn Union Gas and Con Edison). The heating was often faulty. The floor in one of the bathrooms was caving in. Rats would suddenly appear at parties. Some problems were inherent to the conversion; the house is classified as a one-family dwelling and is not intended to host two kitchens and nine people. Gendville and Brooks-Church weren’t registered as the landlords with the Department of Housing Preservation & Development. Instead, they posted signs on their rental properties that warned DO NOT LET ANYONE FROM THE CITY IN. NO EXCEPTIONS. The reason became clear in 2018: After the Fire Department responded to a small oven fire, the FDNY reported the illegal conversion and the couple were fined more than $2,000. Over the past two years alone, according to the city, Gendville has racked up $49,130 in unpaid fines from a host of violations at 1214.

When tenants demanded Brooks-Church take care of the rat situation, he warned them that their “walls will be full of rat skeletons. Their souls will haunt you.” A debate over whether he would shovel snow in front of the home, as required by tenant laws, ended with him writing, “So sue me.” Gendville was kinder but equally unhelpful. “It was a good-cop, bad-cop type of thing,” says one tenant. Another agrees: “Gennaro was the muscle, the henchman.” Tenants would joke about the irony of Brooks-Church sending them aggressive emails refusing to maintain the property above his “Eco Brooklyn” signature.

The rent rose, but tenants felt powerless. As the city’s affordable-housing shortage deepened, finding a room in Brooklyn often felt like choosing between bad and worse. “Trying to find a place in New York is always some level of desperation,” says one tenant, who stumbled across 1214 after a previous housing debacle.

Gendville and Brooks-Church’s business ventures ran like a well-oiled, if extremely tenuous, machine. On the surface, they catered to the upper crunchy crust of Brooklyn, hawking imported wooden toys, prenatal-yoga classes, and rooftop gardens to gentrifiers with money to burn. But it was “yoga on the outside, pure capitalism on the inside,” as one former Area employee puts it. Behind the scenes, Gendville and Brooks-Church were exploiting the city’s growing underclass for a short-term, reliable cash flow: employees working without benefits and tenants paying up to $1,000 each for a single room in an illegal conversion. By this year, it appears, the landlords were pulling in nearly $10,000 a month at Dean Street alone.

They squeezed every drop of money they could out of every setup. Brooks-Church offered workers free yoga classes in exchange for a day of labor in his building business. Gendville offered free classes to guests when the couple began renting out both of their Carroll Gardens brownstones on Airbnb and Vrbo for at least $200 a night. Multiple guests at the Douglass Street listing complained in reviews that it looked as if someone had been living in the rooms right up to the moment they arrived. The couple and their children, according to yoga teachers, would sometimes sleep in the yoga studios because every other property was occupied.

And still they kept expanding. In 2016, as the next wave of gentrification gathered speed, the couple spent $1.4 million to purchase two properties in Flatbush and East New York. They took out additional mortgages on two of their other homes, accruing more than $2 million in debt in only four months. And why not? Brooklyn home sales continued to break records, and the market’s consensus was as giddy as it was unsustainable. “There was no limit,” recalls Jonathan Miller, a New York real-estate analyst and appraiser. “Even though we always know there is a limit.”

It didn’t take long for the limits to assert themselves. By 2017, just as retail spending was beginning to dip dramatically in the face of online shopping, Gendville had 14 Area stores in the wealthiest neighborhoods in Brooklyn. Commercial rents in the city were becoming untenable, and storefront vacancies had doubled in a decade. Gendville’s employees were baffled that she kept relentlessly taking on leases, given how little she seemed to enjoy running a business. “Loretta likes shiny new things,” says Paula Loose, a former yoga teacher.

Others were struck by the contrast between Gendville’s seemingly endless capital and the ragtag conditions in her stores. “Our eyes would get bugged when we’d hear she was taking on another lease,” recalls one teacher. “We’d go, ‘Oh my God, why doesn’t she just get us toilet paper?’ ”

In a profile on the news site Brooklyn Ink, Gendville hinted at an impending pivot. “Online shopping is hurting businesses all over,” she lamented. She had installed nearly $16,000 worth of infrared saunas in one of her studios, which she turned into a spa called Area Sweat. “I’m looking to move into being more health related and less retail,” she said. “More yoga, spa, and vegan food.”

Then, after almost 20 years, Gendville and Brooks-Church’s romantic partnership came to an abrupt and acrimonious end. Gendville began a relationship with a 22-year-old named Shepherd Lantz, who had been working as her children’s manny. Online, Lantz advertised himself as a carpenter, a pet sitter, a waiter, and a handyman. He had modeled in a portfolio of erotic photography; he had been to Burning Man. After he started working at Area doing odd jobs, he and Gendville were seen holding hands and kissing in the back of yoga classes.

Gendville was thrilled over the new romance, but teachers worried about her increasingly erratic behavior. One morning, Setaro came into a studio for a 7 a.m. class to find a group of naked people sleeping under yoga blankets after a party. “When I told Loretta, she was just like, ‘Oh. Okay,’ ” Setaro recalls. Another time, Lantz was found in the studio with an air mattress; one teacher heard he and Gendville had been spending the night on it. A class had to be canceled at the last minute so Gendville could undergo a personal ayahuasca ceremony. In February 2017, she and Lantz were arrested at the Gowanus Whole Foods for shoplifting $1,149 worth of items in a nighttime spree. (The charges were eventually dropped.) The next year, Gendville gave birth to a baby girl. Lantz was the father.

The tenants at 1214 Dean Street were pulled into the drama. “I, LORETTA own 70% of dean street and Gennaro is not sharing his rent collection information with the bookkeeper,” Gendville wrote to an email chain of tenants with Brooks-Church cc’d.

In 2018, Brooks-Church began renting an apartment on Court Street, which he appointed with $30,000 in plant-covered “living walls.” He had clearly begun to move on: “My sex appeal has definitely increased,” he told the Times. “I’m on social dating apps, and they love my living walls.” The hustle continued. Brooks-Church sublet rooms in his new apartment on Airbnb; as tenants at 1214 continued to deal with utility cutoffs and rats scuttling in the walls, guests on Court Street left five-star reviews. That same year, Gendville was charged $17,000 in penalties for renting out rooms at their building on East 54th Street in Flatbush for “illegal transient use.” The fines remain unpaid.

Around the same time, Gendville opened her vegan restaurant, Planted Community Cafe, along with a nascent CBD business. She closed all but three of her yoga studios; some teachers heard she’d paid dearly to get out of at least one lease. In June 2019, she wrote Area employees with an offer. “I am super busy with the new cafe & baby #4 and trying to unwind my responsibilities just a little bit lol,” she said. “I am open to ideas & partnerships or selling leases.” But nothing materialized. Teacher turnover remained high, and those who remained complained of cold studios, spotty Wi-Fi, and broken sound systems. Class prices, however, went up.

Then the pandemic hit. In March, all nonessential businesses in the state shut down. Almost overnight, the revenue streams Gendville and Brooks-Church relied on vanished: The restaurant and yoga studios closed, Airbnb rentals came to an abrupt halt, and a quarter of all New York tenants stopped paying rent. The couple were carrying nine mortgages, totaling $4.6 million, on six properties. Even if the houses they own are worth more than $9 million, as estimated by Zillow, that money in the short term is inaccessible. In April, Gendville requested a continuation on a loan from Citibank, as her yoga teachers began asking her for their last checks. She responded that her computer had been stolen and she was waiting for a loan. The best way to get paid, she said, was to friend her on Venmo. “This is not only irresponsible as a business, but it is cruel,” one teacher wrote to the Area email group. “I am fed up with this.” That Gendville and Brooks-Church tried to move into a house that was still occupied by tenants, in the middle of a highly publicized eviction moratorium, is perhaps the most revealing indicator of their distress. It is also an indication of how little they feared punishment.

One reading of Brooks-Church and Gendville’s faltering empire is a tale of a couple who simply got in over their heads. From what Miller, the appraiser, can surmise, the math stopped working “well before COVID,” given the double whammy of falling retail sales and rising commercial rents. “They can’t keep it going without selling some of the assets,” he says. “They’re running into roadblocks of their own making.”

Another way to look at their downward spiral is as a parable of a housing market that is not primarily intended, or even incentivized, to actually house people. “We don’t finance housing in this country,” says Ron Shiffman, a city planner and tenured professor at Pratt’s School of Architecture. Instead, housing serves as a “financing tool.” The market encourages buyers, whether Saudi princes or the owners of yoga studios, to treat homes like banks, as places to put their money, whether or not they actually live in them. It also motivates developers to build luxury properties with the highest returns, housing fewer residents. In New York, the pandemic brought the dangers of this system painfully to light, as mass economic devastation made many people, even landlords like Gendville and Brooks-Church, suddenly desperate for real-time shelter. “The housing market isn’t meeting the needs of people who are working, who are living, in New York,” Shiffman says. Brooklyn’s runaway success, it turns out, was built on an economic disparity so intense that it has created a microgeneration of gentrifiers like Brooks-Church and Gendville who are now being priced out themselves.

There isn’t a more explicit symbol of a housing market totally divorced from its human context than the eviction attempt at 1214 Dean. The tenants were largely in their 20s and 30s. Many were queer, Black or brown, and employed in low-wage service jobs. In April, after several of them were laid off, they told Gendville and Brooks-Church that they would be withholding their rent. The following month, they received a one-line email from Brooks-Church informing them that the house would be put on the market “within the next month or two.” Then, on July 2, tenants say Brooks-Church suddenly showed up at the house, demanding they pay their rent. He woke up two women who were sleeping in a room on the top floor; they jumped up to dig money from their wallets. Another woman who had recently lost her job was in her room, recovering from an emergency craniotomy to remove a mass of brain tumors. After Brooks-Church left, she emailed Gendville, begging for a move-out date of August 15. “I’m under the most stress I have ever been in my life,” she wrote. “I hope you can empathize with my situation. I am sorry this year has happened to anyone.”

“I don’t know who you are,” Gendville wrote back. “Who is this?” The following week, when she and Brooks-Church showed up at 1214 with their kids, they put the woman’s belongings out on the street, including the get-well gifts she had received during her hospital stay.

By August, no tenants remained at 1214. The woman who’d had surgery found a new place, but her rent has doubled. She will be undergoing chemo and radiation for the next nine months and has thousands of dollars in unpaid hospital bills, most of which will likely not be covered by Medicaid. Martinez, who found another rental in Flatbush, says she walked past Planted Community Cafe a few weeks ago. Gendville, who was sitting under a rainbow Pride flag, waved at her manically. “Like you’re for queer rights,” Martinez seethes, “when you’re trying to displace a house with queer people in the middle of a pandemic, illegally.”

There are now 50,000 impending evictions looming in New York. One result of the pandemic is that its devastation is so massive as to create a vast new contingent of housing militants. “Our thing is public shaming,” Imani Henry, the founder and lead organizer of Equality for Flatbush, told The Nation. Now he has an entire army of shamers at his disposal. Out-of-work New Yorkers are suddenly free to dedicate themselves to standing in a neighbor’s yard and screaming at a landlord. The Battle of 1214 Dean Street made it all the way to BoCoCa Parents, the Brooklyn Heights, Cobble Hill, and Carroll Gardens neighborhood listserv, prompting a call for a boycott of Gendville and Brooks-Church’s businesses.

The landlords so far remain unrepentant. Brooks-Church told the New York Post he is being targeted as a white man. He declined to comment for this story; Gendville would say only that there was “no eviction.” In an email to outraged Area Yoga teachers, she sarcastically thanked them “for all of your judgments. Very yogic behavior!” She ended by saying that “I have to go back to ‘work’ … not everyone can sit around judging people and complaining all day.”

The pair have also become coronavirus skeptics. Gendville has been spotted serving at both Planted cafés — there are two now — without a mask. She says she has antibodies. The brownstone at 2nd Street has anti-mask signs in its windows. Brooks-Church recently participated in a U.K.-based online discussion called “Corona Talks,” in which he was described as “outspoken against the civil-liberty issues the lockdown raises.” He has started a new company called Elixir Works, which offers a “delicious and powerful immune booster” containing everything from bee pollen to tree lichen. It costs $37.50 a week, with a monthly subscription.

*This article appears in the August 31, 2020, issue of New York Magazine. Subscribe Now!

No comments:

Post a Comment