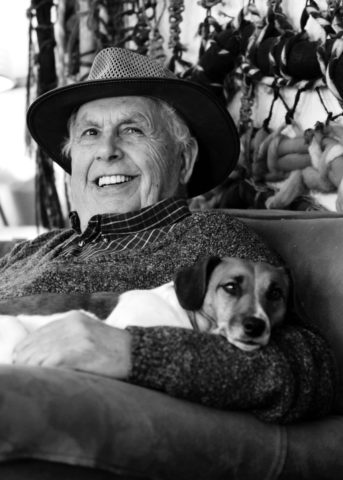

Frans Malan and Niel Joubert tasting wine on the trip to Europe, where they got the idea to start a wine route in Stellenbosch. (Photo: Supplied) Less

We take so much for granted these days – rotisserie chickens in the supermarket, avos and strawberries all year round (even if it goes against nature but we pay for the privilege anyway), not running out of toilet paper, road signs directing us to wine farms…

The better option, it was decided, was to assign a number to each farm which then cross-referenced to a map, because consulting a piece of paper while driving – or arguing with whomever was in the passenger seat and flinging accusations about “someone” not wanting to stop to ask for directions – was just so much safer.

“My mom made the drawings of the first map but they weren’t allowed to put any signs on the roads,” recalled Nora Thiel, daughter of Stellenbosch Wine Routes co-founder Spatz Sperling, of Delheim. “Then they were allowed numbers on a pole. We were number three, Simonsig was number five.

“Number three didn’t mean anything, so my brother Victor and I had to stand out on the freeway with a Delheim sign,” laughed Thiel. “We had to run away from the police.”

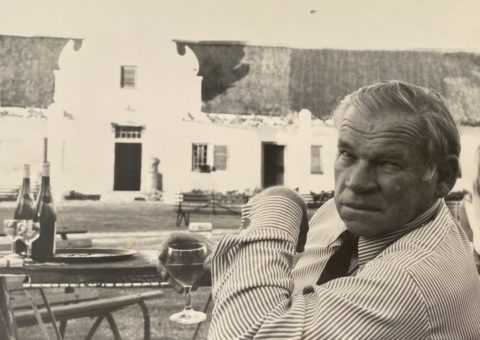

During a trip to Burgundy in 1969, Frans Malan (Simonsig) and Niel Joubert (Spier) discovered the famous Routes des Vins in Morey St Denis and thought it to be a great idea, and could be implemented back home in Stellenbosch. Malan had seen something similar in Bordeaux as well. When they returned, they roped in Sperling to put this plan into action. Back then, the industry was controlled by the government-funded KWV and co-operatives due to oversupply, vineyard owners could not sell wine under their own labels, and pricing was fixed. Joubert was a director at KWV and a member of the Liquor Board, which proved invaluable, said Malan in a 1992 interview in Wynboer magazine.

“My dad had to go around trying to convince people to join. We used to joke that my dad did all the work and Frans and Niel were the brains,” said Thiel. “He wrote a couple of letters but got no reply. When he told the others, Frans said ‘no man, you can’t just write letters, you have to go see them!’, so he drove from farm to farm.”

They took some convincing but once they saw the value of opening their farms to the public, they began to show interest, said Malan in the Wynboer interview.

“It was our intention, and we believed it would be in our own interest, to promote South African wines and in particular, Stellenbosch wines. We encouraged producers to bottle wines under their own personal labels and we stressed the fact that by opening their farms to the public, the wine culture could be expanded as people would learn more about wines.”

Thiel spoke of how “incredibly good” the route was – and is – for South African wine education, to bring people to the farms and make them feel part of it. “Today still, the biggest role we play is educational. And to make it an experience visitors feel comfortable with.”

One should also note that as the local wine industry was controlled at the time, it was also boycotted by the world at large due to apartheid. South African wines were not welcome on international tables until the early 1990s. So let’s take a moment here to pause and reflect on how much things have changed for the better.

Beginning with five farms which were bottling their own wines in 1971, the number quickly grew to 11, and by 1973, 19 farms were members of SWR. In 2021 there are more than 120 wine and grape producer members in the Stellenbosch Wine of Origin region, making this the largest wine route in South Africa, almost as big as all the others combined. In fact, there are five sub-routes, offering a range of experiences and activities. It’s not just wine tasting any more, Dorothy. This is wine tourism at its best; an industry that contributes R7.2-billion to the GDP per year, with accommodation, events, sports, restaurants (more than half of member wineries have incorporated food-related experiences) and weddings.

It wasn’t easy in those early days. Thiel remembers up to 600 visitors a day in the 1980s, who would use the bathroom in their private home. The tasting room was one table and a few glasses, and wine sales were restricted to 3,000 cases a year – from all the farms combined – and a minimum of 12 bottles could be sold at a time.

“We weren’t allowed to sell single bottles. Initially we couldn’t open on a Sunday, then we were allowed from 11am till 2pm. Wine had to have a cork not a screw cap.

“We weren’t allowed to charge for tastings, so we sold glasses. We weren’t allowed to have a restaurant, the kitchen had to be tiled top to bottom, the dining area had to be carpeted, there had to be two entrances for whites and non-whites … we didn’t have any of that,” said Thiel.

“In 1976, my mom realised visitors would be hungry so we should give them some food. We didn’t have a restaurant licence so we got a hawker’s licence, which allowed food to be made elsewhere and sold on. Ute (winemaker Otto Hellmer’s wife) made bread and snoek pâté, got a few cheeses, which she brought to the old manor house, put them on a plate and served platters from the homestead.

“We even had three sittings a day, for which you bought tickets. My mom says Hartenberg was the next farm to serve food. We did cellar tours and we did vineyard tours, breakfast, lunches, gift shops – entertainment all around to try to keep people busy.”

The SWR founding members are all dearly departed now. On 17 April, 2021 – the official 50th anniversary of SWR – Isabeau Botha shared her memories of her Oupa Niel Joubert on social media:

“Almost 40 years ago, a few days before I turned seven years old, my grandfather celebrated his 70th birthday. At the high point of his (as always) epic birthday party, candles were lit, everyone sang ‘Veels geluk Oom Niel’, and he promptly declared to the guests that they should enjoy only the number zero of Ouma Bonté’s huge number-cake, and gifted me the number seven of the cake – true to his great passion for ‘samesyn’ (togetherness; as in celebrating)! This bigger-than-life gesture even trumped our favourite, Ouma’s famous Casimir-figure cakes specially made for grandkids’ birthdays.

“This is how and why I remember my Oupa Niel Joubert, who is honoured as one of the founding fathers of the Stellenbosch Wine Routes, heralding the birth of wine tourism in South Africa. I salute them for their visionary creation!

“My Oupa was not only a ‘baanbreker’ (pioneer) and a visionary thinker, but also a jolly and good fellow.

“Life was always exciting when my Oupa was around. My father Chris remembers that as a director of the KWV, Oupa Niel was adamant about the annual address of representations to increase the price of wine with a penny … yes, that’s one penny (for interest’s sake, in the early days of the wine route, a case of 12 bottles of Pinotage would put you back R6.50 and a case of Riesling only R4.50). My aunt Helena remembers Oupa Niel piloting a food and wine festival in the Stellenbosch town hall, leading to the birth of the Stellenbosch Fynproewersgilde and the ever-famous Stellenbosch Food and Wine Festival.

“To me, one of his 12 grandchildren, he was just the best Oupa in the world. He always made time for us. Even if this meant deep-sea fishing at 4am. He also taught us to dream, think and do. I knew him for 16 beautiful years. Yes, he often did things a bit out of the very square Afrikaner box. Oupa Niel was not only a legendary ‘groot gees’, he really personified the word ‘gees’ (a hearty spirit) – he was kind, jovial, exuberant, and enthusiastic about life, good food, great wine, and even greater company. He was bold in inspiring others to try out new ventures at a time when selling wine under your own label was a foreign concept.

“‘The wine route opened up the farm to Jan Publiek,’ my father Chris says. ‘You did not visit a sheep farm or a grain farm, but you did visit a wine farm to taste wine … which created an opportunity for a restaurant on the werf … and then for a harvest festival, an art gallery, a market and more. The farm experience still holds tremendous future potential for agritourism’.”

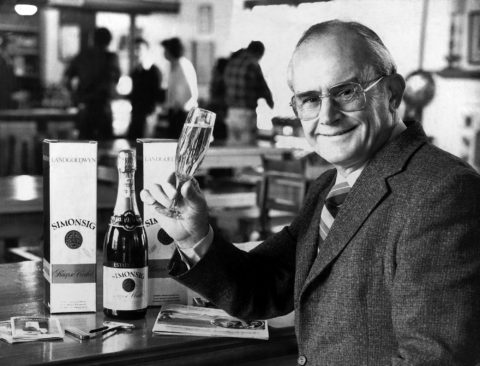

Frans Malan was not only a co-founder of SWR but was also the first South African winemaker to produce a bottle-fermented sparkling wine; Kaapse Vonkel celebrates its 50th vintage this year too, an equally significant milestone. His son Johan and grandson Michael have continued the family tradition. Current senior winemaker Charl Schoeman – whites and Cap Classiques – told us that Michael made the reds, and while Johan has moved more into a marketing role, he is still active in the cellar.

“The industry was quite regulated with most of the wine made by KWV and Stellenbosch Farmers’ Winery. Frans installed stainless steel tanks in an effort to up the quality of the wines, but prices were always the same,” he said.

The first wine bottled under the Simonsig label was Chenin Blanc in 1968, followed by Pinotage in 1970. Kaapse Vonkel was made in 1971 and released in 1973. “Frans visited and loved the Champagne region in France and after he visited, he was inspired with a vision to make a methode champenoise,” said Schoeman. “He had no access to Chardonnay and Pinot Noir grapes, which are the predominant varietals, so he used Chenin Blanc.”

When it was launched, Kaapse Vonkel was the most expensive South African wine on the market at – wait for it– R3 a bottle. The market was full of carbonated sparkling wines, mostly sweet, so Malan had to somehow convey the message to consumers why they should pay more for this bone-dry wine. With each bottle, he sent out a pamphlet with illustrations and photos showing the method, and the label said it was fermented IN THIS BOTTLE, like that, in capital letters.

“About 10 years later some of the other wineries started making Cap Classiques and there are now around 200 producers making more than eight million bottles annually,” said Schoeman. “It is one of the most exciting and vibrant wine categories in SA at the moment. It’s expensive to make, so it has to be premium quality. The industry standard is of such high quality you rarely buy a Cap Classique, which is disappointing.”

Sometimes the benefit of doing something first is that it can never be taken away, said SWR chairman Mike Ratcliffe pragmatically. “It’s always a useful thing, and you can use it over and over.” As custodians of the legacy created in 1971, SWR is committed to protecting its brand and future.

“Stellenbosch is a diverse region, a big region, and it’s not an opinion but it’s a fact that in the sense of a wine perspective, Stellenbosch rules the roost.

“If you enter any kind of competition, we’ll steamroll the results and it’s not always because of the quality – although I like to think it is – but also because of sheer volume.

“With that size comes responsibility, and we take that quite seriously, consciously promoting the industry and growing the product. We have a vast concentration of well-established role players; heritage brands like Vergenoegd to Meerlust, to Kanonkop and Verlgelegen. No one else has that.

“We also have this really developing young gun culture, garagiste and small hippy winemakers making barrels here and barrels there. A new phenomenon which we are grappling with, I won’t lie, are those attracted to the Stellenbosch brand from outside, such as Elgin and Franschhoek, which are launching Cabernet Sauvignon made with grapes from Stellenbosch, and using the name.

“A Robertson brand is looking at setting up a tasting room in downtown Stellenbosch and while we can’t stop them, we have to ask questions about what they are doing. We also have Brampton; we engaged with them a number of years ago and said ‘guys, you’re kind of trading on our laurels’. They took our comments to heart and are now rolling out two or three Stellenbosch wines.”

The Stellenbosch Wine Routes has two mandates: generic wine promotion and wine-tourism promotion. Generic wine promotion is building brand Stellenbosch to be associated with quality and, over time, raising the price of the grapes, explained Ratcliffe.

“The wine tourism side is to make sure tourists who come to town are structured and organised and know where to go. If they love red wine, there’s a route; a white route, a sparkling route; and to connect with accommodation and restaurants,” he said.

“It’s amazing how little tourists know, and how little they care. They want to come to Stellenbosch because it’s the place to be. Once they’re here they will do whatever they’re told, in the nicest way. People want to be guided.”

The celebrations in Stellenbosch are planned to last a full year, until April 16, 2022, culminating in a post-harvest extravaganza of a party. At the end of August 2021, a 10-day festival is planned, called Wine Town Stellenbosch, which will be scaled according to the moment (and by that we mean Covid). There’ll be a marathon, a four-day golf tournament, restaurants are already talking about a “Restaurant Week”, lots of excellent deals on accommodation, a big bottle festival, a fine wine festival, and it will be the launchpad for an international braai broodjie competition.

“It’s tongue in cheek but the ultimate goal – we are rolling with it – is that we want the Olympic committee to consider braaibroodjie for inclusion,” said Ratcliffe with a cheeky grin. “It’s totally ridiculous but we want to make it a spectator sport. We’ll close off Church Street, with braais down the middle, and grandstands.”

If anything can get people to take sides, it’s a braaibroodjie. Ratcliffe envisages classic and gourmet categories, with entries being paired with Stellenbosch wines for judging. He sees television coverage, big screens, roaming cameras and Mexican waves.

“We’re holding a one-day workshop in Kayamandi in July, and the winner gets a free entry into the competition. We’ll have a Joburg invitational, a Durban invitational, and if we can pull it off depending on Covid, fly in a Michelin star chef because it’s appropriately silly,” he said.

I’m in. Who’s with me? DM/TGIFood

For more information, email info@wineroute.co.za or call 021 886 4310. Learn more about Stellenbosch’s reputation for fine wines, food, history and culture at www.wineroute.co.za and www.visitstellenbosch.org.

Use @stellwineroute to connect with Stellenbosch Wine Routes on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram.

Interesting anecdotes

The Stellenbosch Wine Routes still has its original phone number. In the 1980s, the number was 4310 at its first office at 33 Plein Street. Today, it is 021 886 4310.

The first wine festival in South Africa was hosted in the Stellenbosch Town Hall in 1973 in collaboration with the Stellenbosch Fynproewersgilde.

Founding members of the wine route were instrumental in the establishment of the Wine of Origin system.

Frans Malan and his fellow founders of the Stellenbosch Wine Routes challenged the road authorities and in the late 1970s, the first road signage for wine farms was approved.

No comments:

Post a Comment