BERLIN, GERMANY DECEMBER 01: SpaceX owner and Tesla CEO Elon Musk arrives on the red carpet for the Axel Springer Award 2020 on December 01, 2020 in Berlin, Germany. (Photo by Hannibal Hanschke-Pool/Getty Images) Less

In October 2018, Virgin Group founder and billionaire Richard Branson stated on his blog: “While those investigations are ongoing and Mr Khashoggi’s whereabouts are not known, I will suspend my directorships of the two tourism projects. Virgin will also suspend its discussions with the Public Investment Fund over the proposed investment in our space companies Virgin Galactic and Virgin Orbit.”

Just a year earlier, Branson had announced a deal with Saudi Arabia’s Public Investment Fund in the form of a non-binding memorandum of understanding (MOU), for an investment of $1-billion in Virgin Galactic, Virgin Orbit and The Spaceship Company.

But now, the subsequent investigation into the disappearance of a Washington Post columnist Jamal Khashoggi was pointing the finger at Saudi Arabia’s crown prince Mohammed bin Salman Al Saud, as being behind the disappearance, torture, murder and dismemberment of Khashoggi. It was amid the global outrage that Branson suspended the negotiations.

Nevertheless, Virgin Galactic pushes on and by December 2018 hits a milestone as the VSS Unity reaches space safely. A moment 14 years in the making and long past its scheduled date. An emotional Branson can be seen crying on the day in a Virgin Galactic video titled “A Letter To My Grandchildren – Sir Richard Branson – VSS Unity Flight”.

More successful test flights follow. A year later, things are looking up. After a merger with the investment firm Social Capital Hedosophia, Virgin Galactic goes public on the New York Stock Exchange in October 2019, becoming the first spaceflight company to do so. However, in February 2021, The Washington Post breaks the story that, upon inspecting the spacecraft after a successful test flight in February, “company officials discovered that a seal running along a stabiliser on the wing designed to keep the space plane flying straight had come undone – a potentially serious safety hazard”. This had gone unreported at the time, but “after the February 2019 flight, Virgin Galactic grounded SpaceShipTwo. A financial record released later that year shows the company was losing about $17-million a month, with only about $86-million left in cash and cash equivalents by the end of September”, Nicholas Schimdle, a writer who had been embedded with the company, wrote in an essay adapted for The New York Times, from his book, Test Gods: Virgin Galactic and the Making of a Modern Astronaut. Amid Branson’s cosmic setbacks, the Covid-19 pandemic hits, travel comes to a standstill, and his various travel businesses take a hit.

By 16 April 2021, the Observer reports that “last year, Branson cashed out $500-million worth of Virgin Galactic shares as the pandemic took a toll on Virgin Group’s other travel and leisure businesses. This week, the billionaire dumped another $150-million of Virgin Galactic stock.”

It hasn’t helped the company that in recent years, as it seemed to be facing numerous major setbacks, the other two famous billionaires in the race seem to be thriving. Jeff Bezos’s Blue Moon continued to work guided by its motto “Gradatim Ferociter”, Latin for “step by step, ferociously”.

Back at that May 2019 presentation, as mentioned in part one of The Galactic Game, Bezos is just past the halfway point of his 51-minute presentation of the culmination of the ferocious steps the company had taken over its first two decades, as well as unveiling the many future steps it would be taking. The New Shepard he unveiled earlier will undoubtedly present yet another major setback for Virgin Galactic’s space tourism dream. In fact, just two years later, on 29 April 2021, Blue Origin tweets: “It’s time. You can buy the very first seat on #NewShepard. Sign up to learn how at http://blueorigin.com. Details coming May 5th. #GradatimFerociter”. And on 5 May 2021, an online auction goes live on Blue Origin’s website: “On July 20th, New Shepard will fly its first astronaut crew to space. We are offering one seat on this first flight to the winning bidder of Blue Origin’s online auction. Starting today, anyone can place an opening bid by going to BlueOrigin.com.”

But for now, in May 2019, Bezos has turned his attention to the moon for the latter part of his presentation, and the second vehicle he unveils a few minutes later, Blue Moon, will up the stakes for Elon Musk’s SpaceX.

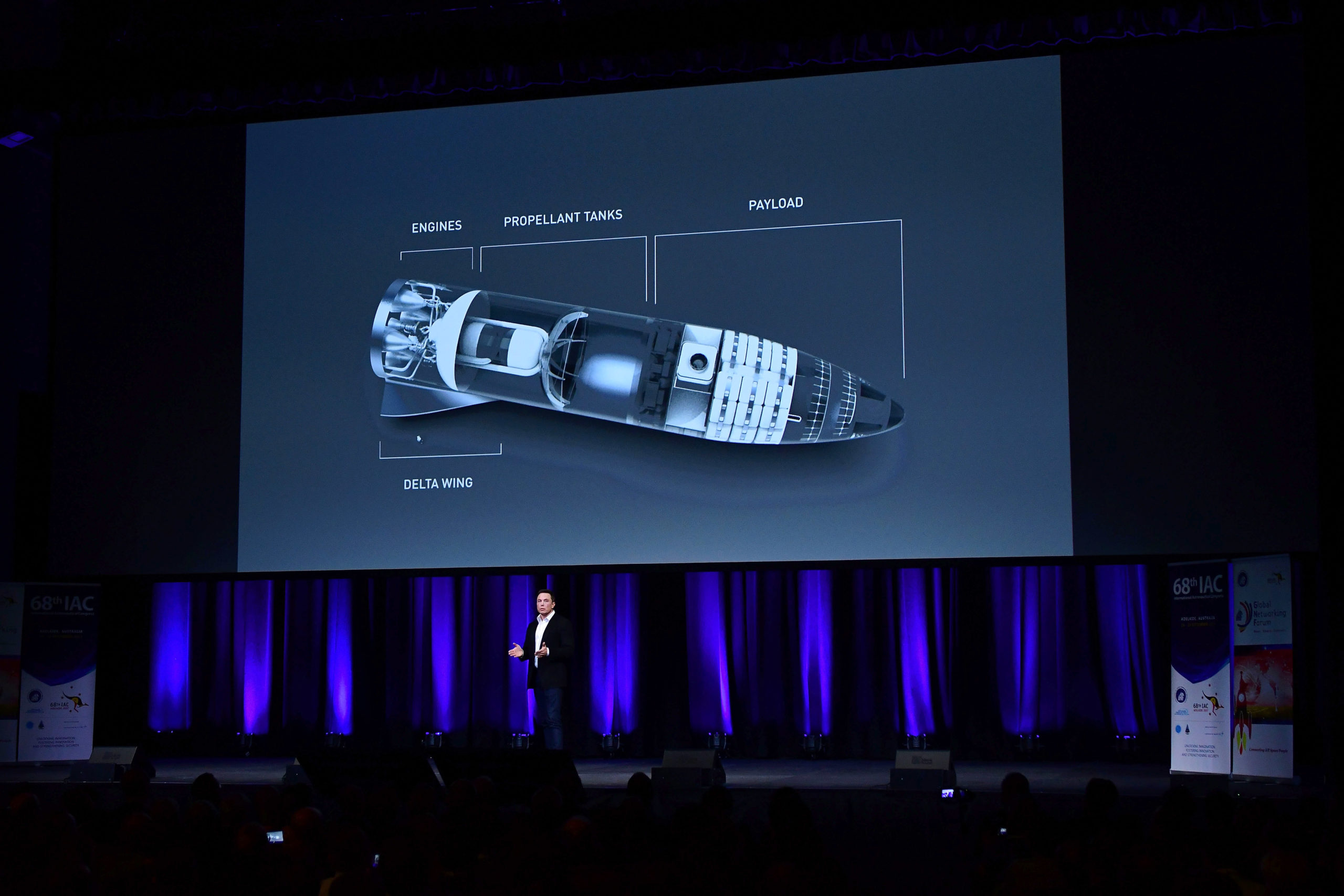

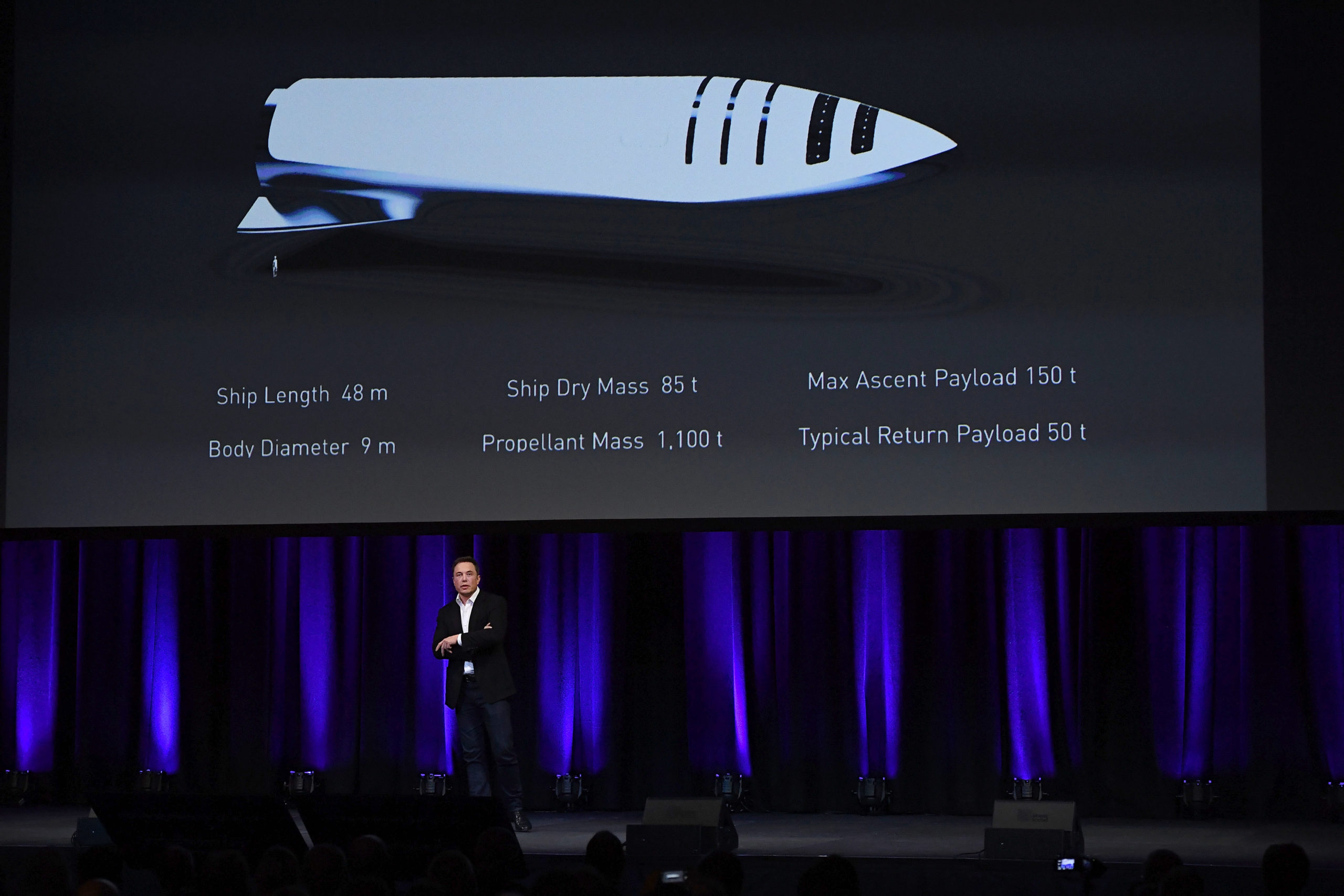

Just a few years earlier, Musk gave a keynote address of his own, laying out his vision for the future. Unlike Bezos, whose vision for humankind does not stray too far from its current habitat, Musk imagines an interplanetary species: “I think there are really two fundamental paths; history is gonna bifurcate along two directions. One path is we stay on Earth forever, and there will be some eventual extinction event… The alternative is to become a spacefaring civilisation and a multiplanet species, which I hope you agree is the right way to go,” Musk tells the audience during that speech on Tuesday, 27 September 2016 at the International Astronautical Congress in Guadalajara, Mexico.

The way he sees it, that journey will start by colonising Mars and turning it into a habitable planet, and he is working on the vehicles that will get humanity there, as well as the technology we will need to live on Mars. He says Mars emigration will eventually be possible at a price equivalent to the “median cost of a house in the United States”, which he estimates at $200,000. “Almost anyone, if they save up and this is their goal, they can ultimately save up enough money to buy a ticket and move to Mars, and Mars would have a labour shortage for a long time… jobs would not be in short supply,” the billionaire tells his audience.

Although it does not go as far back as Bezos’s, Musk’s interplanetary dream is one he has held on to for a long while, at least since the founding of SpaceX. An article penned for the States Frontier Foundation and published back in 2001, states: “Describing permanent settlement of Mars as ‘a positive, constructive, inspirational goal capable of uniting humanity at a critical time’, dot-com entrepreneur Elon Musk has pledged a substantial portion of his personal fortune to realising that goal, beginning with a proposed $20-million technology-demonstration Mars lander to be launched perhaps in 2005.”

Beyond demonstrating his commitment to space exploration, it is arguable that the initial $20-million investment also showed his naïveté about all things space at the time. Speaking about that early phase in a 2012 interview with American space and technology journalist Miles O’Brien for a PBS Newshour special, Musk said that initially he “wasn’t going to start a rocket company. What I wanted to do was to try to get public interest in sending people to Mars… And I came up with this idea to do ‘Mars Oasis’, which was to send a small greenhouse to Mars with seasoned, dehydrated nutrient gel. When you’d land, you hydrate the gel and you have a little greenhouse on Mars. So this would be the furthest that life’s ever travelled.”

In pursuit of that Mars oasis Musk picked up the phone and called Jim Cantrell, then an aerospace consultant who had worked on numerous projects including a joint French-Soviet Mars programme. Cantrell told Esquire magazine in 2012, recalling that 2001 phone call: “I had the top down on my car, so all I could make out was that some guy named Ian Musk was saying that he was an internet billionaire and needed to talk to me. I’m pretty sure he used that phrase, ‘internet billionaire’. I told him I’d call him back when I got home, but when I called, I got a fax machine… Then my phone rang. I asked him what was with the fax machine. He said, ‘I don’t want you to know my cell number’. Then he launched right into the same pitch he has now. ‘I want to change mankind’s outlook on being a multiplanetary species.’ I listened, and he said, ‘Can we meet this weekend? I have a private jet, I’ll fly to your house’.”

By October 2001, Cantrell and Musk were in Moscow negotiating with the Russians to buy used ballistic missiles to convert into launch rockets, and according to Cantrell’s retelling, Musk was seen as so much of a novice that one of the Russian missile designers literally spit at them. In February 2002 they would be back again, meeting more Russians. By this time Musk wanted to buy three ballistic missiles for a total of $21-million, but the Russians wanted $21-million for one. “They taunted him… They said, ‘Oh, little boy, you don’t have the money?’” Cantrell tells Esquire.

On the flight back to London after yet another unsuccessful attempt to buy the equipment they needed, Musk looks up from his spreadsheet and tells Cantrell that he thinks they can build their own rocket: “I looked at it and said, I’ll be damned – that’s why he’s been borrowing all my books. He’d been borrowing all my college textbooks on rocketry and propulsion. You know, whenever anybody asks Elon how he learnt to build rockets, he says, ‘I read books’. Well, it’s true. He devoured those books. He knew everything. He’s the smartest guy I’ve ever met, and he’d been planning to build a rocket all along.”

Just seven years into building SpaceX, Musk had blown through $180-million made during his internet millionaire days. Not to mention he was also going through a divorce and trying to build his electric car company, Tesla. Finally, after a cash injection of $20-million from outside investor, billionaire Peter Thiel, on 8 September 2008 the Falcon 1 had its first successful launch. By Christmas that year, “Nasa awarded SpaceX a $1,6-billion contract to haul at least 20 metric tons of cargo to the international space station over 12 planned flights,” according to space.com.

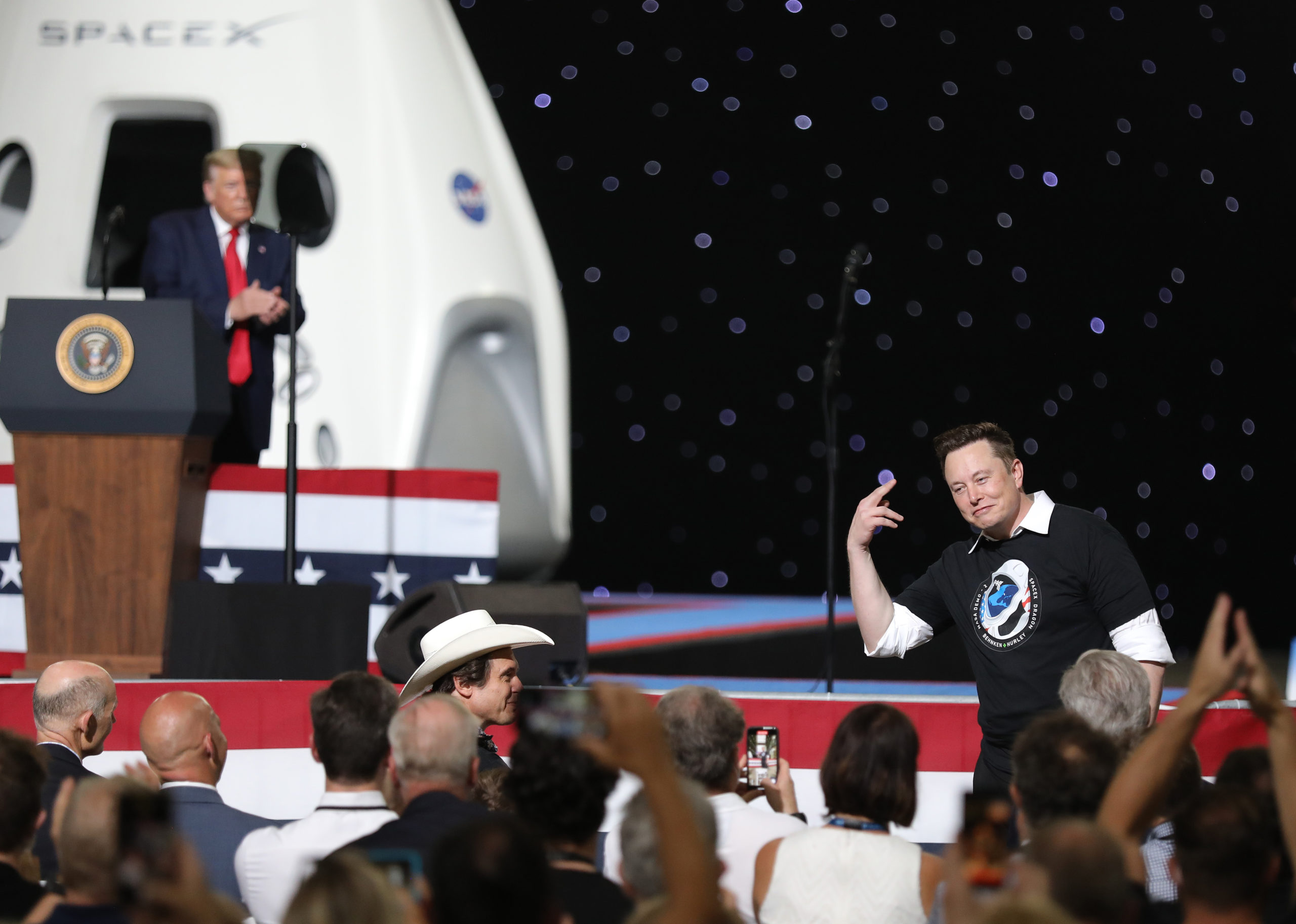

However, the road towards realising his Martian dream would have numerous challenges, explosions and battles that would see Musk go to court against its key client, the Pentagon, when he felt SpaceX had been denied contracts unfairly; contracts which had favoured Bezos’s Blue Origin and its partners. Although Musk’s goal has always been Mars (and evolved to that by building a reusable rocket), when Nasa launched its Artemis Program in 2017 during the Trump administration, to take astronauts back to the moon, Musk announced shortly after that another rocket he had been working on since 2012 – later known as Starship – would be taking Japanese billionaire and founder of the lunar tourism project, dearMoon, Yusaku Maezawa, on a flight around the moon in 2023.

In May 2019, when Bezos unveiled Blue Origin’s lunar lander, Blue Moon, Musk took a screenshot of The New York Times article about the presentation, scratched out the word “Moon” on the picture of the vehicle, and replaced it with “Balls” so that the logo read “Blue Balls” and tweeted it with the caption: “Oh stop teasing, Jeff.”

According to Bezos, his road to space will be made possible in part by building a base on the moon. “We were given a gift, this nearby body called the moon. One of the most important things we know about the moon is that there’s water there. It’s in the form of ice… and water is an incredibly valuable resource,” he tells a crowd. He goes on to describe how Blue Moon will make it possible to transport everything needed to create infrastructure on the moon.

As things stand, in May 2021, SpaceX’s contract to be the first to take Nasa’s Artemis Project to the moon remains suspended, while Blue Origin and Dynetics make their case against it. While both Musk and Bezos have expressed noble intentions for humanity to justify space exploration, water on the moon and asteroids to build O’Neill colonies are hardly the only rewards in space. The space mining industry is already valued at trillions of dollars, and discussions continue to work out the terms.

Then, of course, a little closer to Earth, Musk is on a mission to build Starlink, a controversial constellation of satellites in low-Earth orbit that he promises will provide “high-speed, low-latency broadband internet”, and undoubtedly make Musk far richer and more powerful.

US policies have made it possible for these civilians to rise and get ever closer to becoming something akin to space emperors. Bezos, Musk, and to a lesser degree Branson, are also seemingly leading the space tourism race. However, outside the US, space is still mostly a game of governments. There are eight leading spacefaring nations and they all want a piece of the pie. Once again in human history, would-be empire builders scramble for a cut of a new colonial exercise.

In part three of our space opera, Cosmic Colonisation: The scramble for Space, we take a closer look at the nations, the new space treaties and the rewards that await, as well as the space pollution that follows. DM/ML

No comments:

Post a Comment