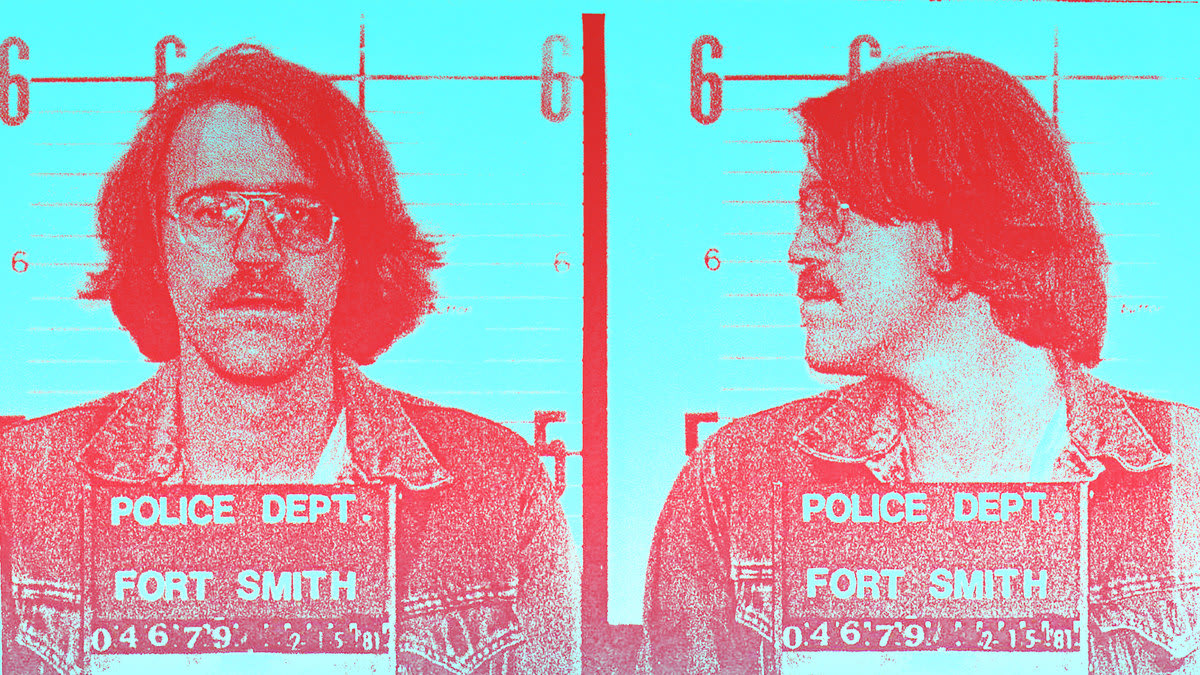

Photo Illustration by Sarah Rogers/The Daily Beast / Photos Courtesy Arkansas Dept of Corrections/Kelly Duda

No one got hurt, no one got killed. But Rolf Kaestel’s toy gun stickup landed him in jail—and 40 years later, he’s still fighting to get out.

By Kate Briquelet, Senior Reporter DAILY BEAST

On a Sunday night in February 1981, Rolf Kaestel robbed an Arkansas taco restaurant using a toy water gun. No one was injured in the stickup. He stole $264—and was sentenced to life in prison.

Forty years later, Kaestel is still behind bars for aggravated robbery. His penalty is unusually severe, supporters say, for a crime without injuries or even a physical altercation.

This year could be the 70-year-old inmate’s final shot at redemption, a taste of freedom for however many good years he has left. Kaestel’s fate now rests in the hands of Republican Gov. Asa Hutchinson, who denied him clemency in 2015 and is expected to decide on his latest application any day now. Should Kaestel be rejected again, he must wait four more years to reapply to the Arkansas Parole Board, which will again send its recommendation to the governor. Under state law, inmates with life sentences aren’t eligible for parole unless the governor commutes their sentence.

But no one, not even the former prosecutor in the case, is demanding that Kaestel remain behind bars. Since 2012, the parole board recommended clemency three times, but Hutchinson and his predecessor Mike Beebe declined to grant it. The victim of the crime, Dennis Schluterman, has spent years pleading for Kaestel’s release. “It’s time for his break to come. He needs to be set free,” Schluterman said in a video recorded outside the Arkansas State Capitol and delivered to Beebe’s office in 2013. “And if you really want to know, I believe that the state owes him. I know you wouldn’t see it that way, but this man has paid the price 10 times over, and it’s time, it’s time for you to let him go.”

''You can see how upset I’m getting right now,” Schluterman added, visibly distraught and his voice wavering. “Many nights I’ve been the same way. I just don’t feel like Rolf should have to spend another day in prison.”

In an interview with The Daily Beast, Schluterman said the same. “It’s not right, is all I want people to know and, if possible, to stand up and support us to help him get out.” Schluterman added, “His life’s running out. His time is running out. God, give him a little bit of something. It wasn’t that bad of a crime to be doing that kind of time.”

Kaestel and his supporters are bewildered that the state of Arkansas insists on keeping the aging inmate imprisoned at a cost of more than $20,000 a year—first at the infamous Cummins Unit, then in Utah under an interstate compact—when prisoners accused of more violent offenses are treated more leniently. “I have not been able to make any sense of it,” Kaestel told The Daily Beast in a letter, “not because it’s me or my case but because this kind of thing should not happen anywhere to anyone.”

He’s had a single visitor in the past 22 years: Colby Frazier, a former reporter for Salt Lake City Weekly. Frazier’s 2014 profile called Kaestel “invisible to those who put him there and a mystery of sorts to those who store him,” referring to prison officials in both states punting questions about Kaestel to the other. Kaestel, the writer said, stumbled into “a volatile corner of the justice system—the part that doesn’t rely so much on concrete law, but more on the whims and moods of the human beings who pull the levers.”

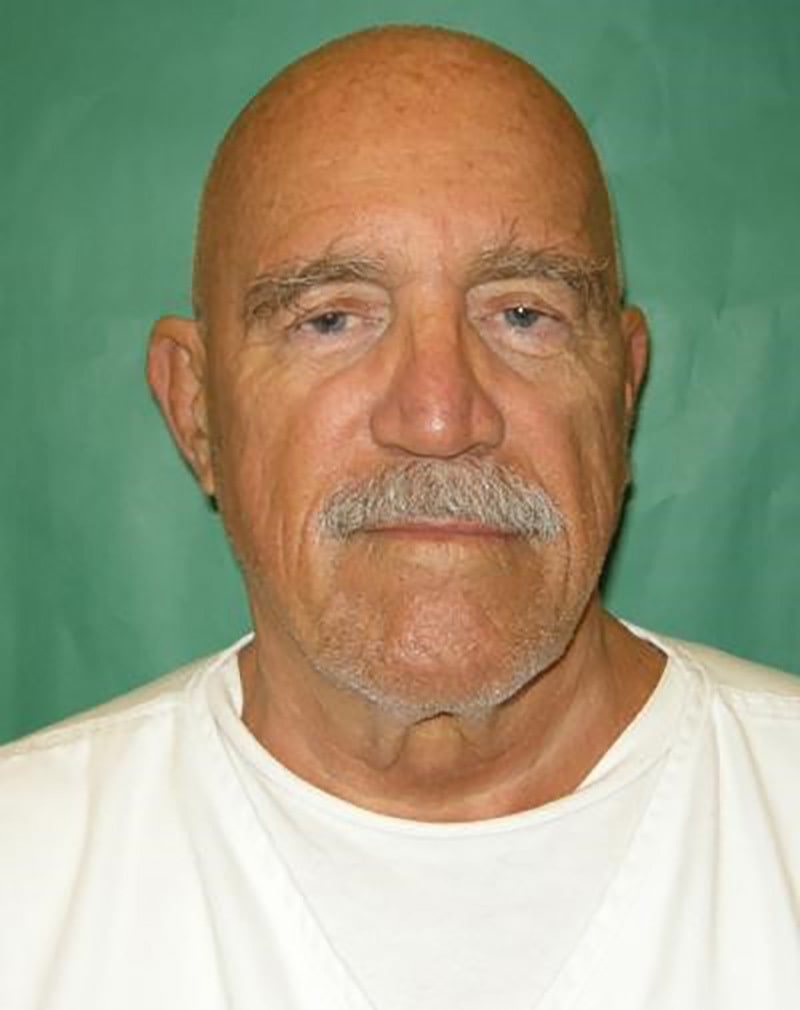

While in prison, Kaestel worked as a paralegal for a local Arkansas firm, edited the penitentiary newspaper, the Long Line Writer, and filed lawsuits in an attempt to win privileges or uphold the rights of himself and fellow inmates. He’s earned three associate’s degrees and enough college credits to be shy of multiple bachelor’s degrees. At Central Utah Correctional Facility in Gunnison, where he was transferred midway through his sentence, he taught astronomy classes and has a job in the prison library. Now bald, missing teeth, surviving COVID-19 and diabetes, Kaestel has remained a model prisoner.

“A man’s life is worth a lot more than $264,” Jones, founding CEO of REFORM Alliance, which seeks to overhaul probation and parole programs, told The Daily Beast. “When people make bad decisions, society should make good decisions about how to correct them and get them back on their way. Obviously Rolf made a bad decision but society made a worse decision in throwing his entire life away over that one day.” Jones added: “I don’t think anybody would think he hasn’t more than repaid his debt to society after decades behind bars for an offense that didn’t cost anyone their lives.”

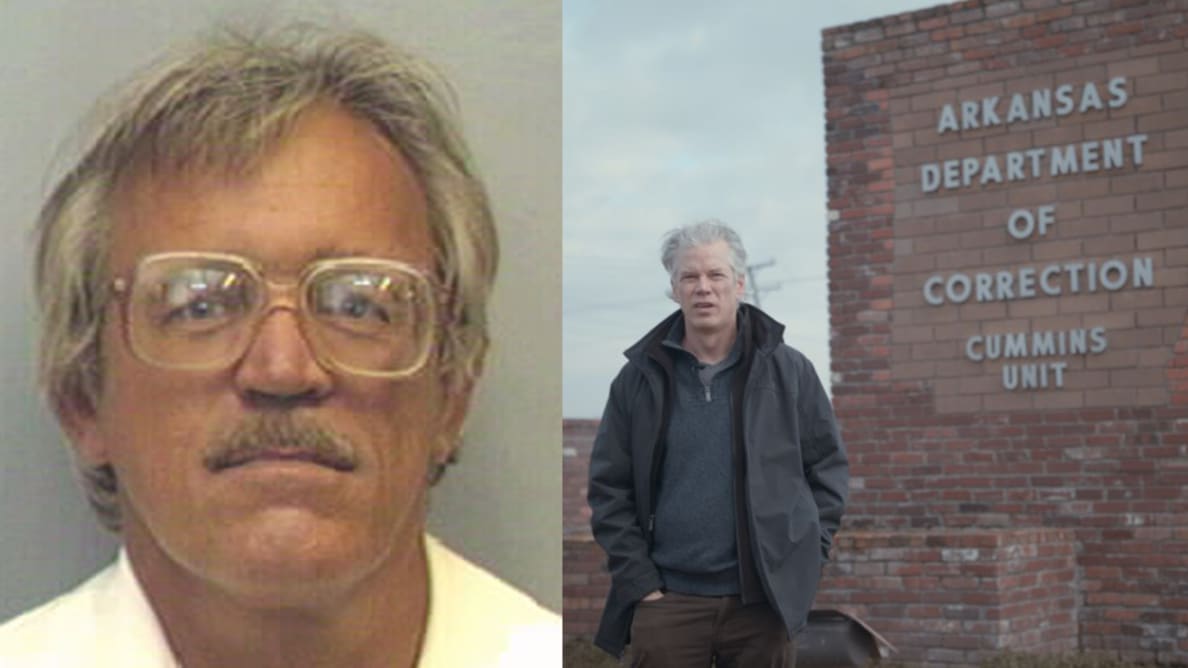

Kaestel’s story is getting attention because of Kelly Duda, an independent filmmaker who talked his way into Cummins in 1999 while investigating the Arkansas prison system’s blood bank scandal, which infected and killed thousands of people across the globe.

Kaestel became a key whistleblower in Duda’s documentary, after which state corrections officials abruptly whisked the gadfly prisoner off to Utah, where he’s been incarcerated ever since. “It is my firm belief that Rolf Kaestel became a political prisoner and was ‘disappeared’ for speaking out,” Duda told The Daily Beast.

Rolf Kaestel was a key whistleblower in a documentary by filmmaker Kelly Duda, who exposed the Arkansas prison system’s blood bank scandal. Here, he speaks in the film.

Courtesy Kelly Duda

“When more serious offenders like convicted rapists and murderers get out in less time, one has to wonder what’s wrong with this picture?” Duda said.

Kaestel has found a staunch advocate in Duda, who never imagined he’d be fighting for a man he met for 90 minutes, 22 years ago. Yet he can’t ignore how Kaestel’s life was tossed away, at an estimated cost of $1 million for taxpayers.

As Schluterman recalls, the night that Kaestel rolled into Senor Bob’s Taco Hut was a cold and slow one. Daylight was retreating in Fort Smith, and Schluterman was in the back room with a coworker when he heard the shopkeeper’s bell. The 17-year-old restaurant worker came out to find two men—Kaestel and his alleged accomplice, Terry Joe Spitler—reviewing the menu on the wall behind him.

“I didn’t pay attention to what they looked like,” Schluterman said. “I just waited for them to order.” Moments later, Kaestel pulled back his coat and revealed the plastic butt of the toy gun. “Do you know what that means?” Schluterman recalls Kaestel asking him.

Realizing he was in a stickup, Schluterman pulled a fistful of money from the register and handed it to Kaestel. “I’ve never been robbed before,” Schluterman, now 57 and a retired machinist, told us. “That’s something you just don’t forget.”

But decades later, Schluterman says he didn’t believe he was actually in danger during the incident. Kaestel “didn’t do more than pull his coat back,” Schluterman said. “He didn’t seem dangerous to me. He seemed more desperate than dangerous.”

“What they did was wrong,” Schluterman said of Kaestel, Spitler and their alleged accomplices. “But man, they were just so far out of town and it was Sunday night and they were out of money, out of gas, it was cold outside. I felt sorry for them after I found out what they did and why they did it. I know it was wrong, but the man shouldn’t still be in prison for that long.”

Schluterman said when he thinks of the robbery, he’s not upset by the incident itself but the many years Kaestel has spent behind bars for it—a period that covers Schluterman’s entire adult life. “When I sit here by myself and think about it, think of all the years he’s lost over it, that’s what gets me down,” he said.

For his part, Kaestel said Schluterman doesn’t deserve the guilt he’s contended with over the years. Schluterman “has been a victim now for 40 years and didn’t deserve a single day of it,” Kaestel told us, “and I am sorry that my actions were the cause of it.”

Before his conviction, Kaestel was a small-time crook, a rebel who spent his twenties on the road, never settling down in one place or job. “All of my life I felt like and in fact was an ‘outsider,’” Kaestel said. “I did not meaningfully become a part of society and I never really wanted to be—because I was ‘afraid’ of being assimilated and made into a replica and mimic of what I was seeing all around me.”

His vagabond existence brought him to the American Southwest, where he gambled in Las Vegas and later connected with a group of wanderers in their late teens and early twenties. They were with Kaestel when he robbed Senor Bob’s Taco Hut but none of them, including Spitler, served any jail time. They testified against Kaestel, smoked pot with Schluterman after the trial, and received funding from the state to make their way home, according to Schluterman’s recollection of events.

Spitler and his girlfriend, 19-year-old Linda Sue Wright, told cops they were driving from California to Iowa when they detoured through the South for warmer weather. A friend of Spitler’s named Selid William Holt, 20, was along for the ride, and they picked up Kaestel as a hitchhiker in New Mexico. Once they got to Oklahoma, the hippie crew pulled over for 17-year-old runaway Alice Joann Wallace at a truck stop.

“When more serious offenders like convicted rapists and murderers get out in less time, one has to wonder what’s wrong with this picture?” Duda told The Daily Beast.

Courtesy Kelly Duda / Arkansas Department of Corrections

By the time they reached Arkansas, they’d run out of funds. In his police statement, Spitler said, “We got off the freeway to look for a church or something, where maybe we could get something to eat and maybe get some money for gas. While we were driving around Ft. Smith, Rolf came up with the idea to rob someplace. I didn’t really want to do this, but we were out of money and hadn’t eaten in a couple of days.”

Wright also told police that Kaestel “came up with the idea” and that he’d declared he wouldn’t work for his money; he’d take it from someone else. “When I first heard them talking about it, I thought they were joking, but I found out later that they weren’t,” she said of her male co-passengers.

They cruised past Senor Bob’s Taco Hut in Wright’s 1976 green Dodge sedan, and according to Wright, “somebody said that it looked like an easy place to hit.” They parked down the road, with Holt as the getaway driver while Spitler and Kaestel went inside.

Schluterman told cops that he was manning the front counter around 7 p.m. when two men entered. When Schluterman asked for their order, one of the men opened his jacket and showed him the butt of a gun—the realistic-looking toy pistol—in his waistband. “You see that,” the suspect said, before Schluterman handed over a wad of bills totaling roughly $274, per the police report. (Some media reports said the stolen cash totaled $264, while a police report said $274 was taken. Another police document said $242 was tagged into evidence.)

Kaestel remembers this moment similarly. “There were no customers inside and no one was behind the register,” he told The Daily Beast. “I had just begun to walk around the counter to open the register myself when he entered from a back room. I don’t recall saying anything to him—everything was implicit in the encounter itself, I think. He was actually very calm and collected and casually got the money and handed it to me when I then asked him to do so. And, I turned and left. There were no overt threats or acts. It was over in a few seconds.”

About 25 minutes later, an animal control officer spotted the green Dodge at a Roadrunner gas station, which happened to be across from the local Arkansas State Police troop headquarters. Kaestel and his alleged accomplices had just exited the convenience store when cops descended on the vehicle.

Officers searched the car and found the toy gun on the floor along with $179.

Rolf Detlev Kaestel’s upbringing was as unusual as his prison sentence, one devoid of love, role models or even knowing the identity of his biological parents. He’s never seen a copy of his German birth certificate despite attempts to obtain one.

Born in Coburg in 1951, Kaestel remembers growing up in what he believes was a post-war orphanage run by nuns. At age 7, he was knocked unconscious after tumbling from a slide on a playground. Not long after the incident, he remembers meeting a woman who exited a black sedan, presented him with a bounty of candy and introduced herself as his mother. She announced she was taking him home for good. “I was a kid and I just went along,” Kaestel told us. “I suppose that it is possible that she is my mother but for whatever reason gave me up to the state or directly to the convent, but that remains a mystery.” The woman and her husband, who was in the U.S. Air Force and is believed to be Kaestel’s stepfather, enrolled him in an American school to learn English.

His adoptive family would relocate to Maxwell Air Force Base in Montgomery, Alabama, but Kaestel doesn’t have warm or happy memories of them. “To this day I have no memory whatsoever of ever having had even a single meaningful conversation with my parents,” Kaestel said. “Whenever I asked questions about me, or them, or Germany—or whatever, they were extremely evasive and even as a kid my intuition indicated that something just was not right about that.”

“They were just ‘adults’ whom I was compelled to be with because I was a kid,” Kaestel added. His parents weren’t physically abusive, he said, but their lack of interest, tenderness or concern toward him gave him a freedom atypical for children his age. “They were not—and I did not perceive them as being abusive toward me, although I suppose that their chronic lack of expression of common love and care toward me is seen by some as an abuse of a kind,” Kaestel said. “They also both became alcoholics later, and that too may well constitute a kind of abuse.” By the time he was 10, he’d run away several times—to explore the world around him, he insists, not rile up his undemonstrative parents.

Kaestel was told most of his relatives died in World War II, and that his biological father might have been a pilot in the German Luftwaffe who met his mother in a field hospital after his plane was shot down. “This entire background remains a mystery to me for the most part,” he said. “For example, I still don’t know my real birth name.”

Rolf Kaestel’s latest mugshot. He’s been in prison for the last 40 years for a small-time robbery in which no one got hurt.

Arkansas Department of Corrections

In Montgomery, Kaestel was a troublemaker, swiping his parents’ cigarettes and stealing cars to see a wealthy girlfriend, whose parents filed a restraining order against him, City Weekly reported. He was expelled from school in seventh grade and never returned to complete his public education.

As a teenager, Kaestel stole to eat, then to get another tank of gas, and eventually to pay for everything he’d otherwise need to pilfer piecemeal. He didn’t have typical kid dreams—of growing up to become a fireman, doctor, or movie star. He only wanted to see the world, “to travel the planet that I was born onto,” he said. “Eventually, that led to a deep desire to go to Jerusalem, to visit the Egyptian Pyramids, and to explore Madagascar—where so many unique and strange animals and other fauna existed (ditto for Australia),” Kaestel said. “And that youthful yearning created the wanderlust in me that I suppose lies even at the heart of the listlessness that eventually developed into criminality.”

In 1966, the Kaestels returned to Germany, where Kaestel searched for his real father while living at Wiesbaden Air Base. There he aided American G.I.s. who stole goods from the post exchange to hawk on the black market. “I was their mule, and they eventually adopted me as a mascot because I spoke German and helped them access places that non-Germans were not otherwise allowed into,” Kaestel said.

But the scheme caught up with the 15-year-old Kaestel, who landed in a juvenile detention center in Frankfurt for 11 months. He said his parents didn’t tell a German judge he was a naturalized American citizen, a fact that would have prevented the country from jailing him. “On a fluke I was able to yell out of the window in my cell to an American MP three floors below saying that I was an American juvenile being held incommunicado here,” Kaestel said. The American military police officer didn’t pay attention until Kaestel yelled out his stepfather’s Air Force service number. Military personnel immediately removed him from the facility, and Kaestel was expelled from Germany until age 21.

When Kaestel and his parents returned to America, he went out one gate at New York’s JFK airport and they exited another: “I never saw or communicated with them again.”

His military pals persuaded him to join the U.S. Army Airborne but when Kaestel arrived for his induction in Syracuse, a recruiter told him to return in a month because of a problem with his paperwork. “But, I decided that the Army had had its chance,” Kaestel said, “and went out into the parking lot, stole a car, and went back to Montgomery, Alabama.”

Once he arrived, he discovered his old girlfriend had moved on. Heartbroken and aimless, Kaestel was arrested days later for burglarizing a store. An old Air Force neighbor turned jail guard recognized him in the holding cell, and the man and his wife took Kaestel in. “It was the first real home life I had experienced,” Kaestel said.

That home didn’t last for long. When the guard’s son had been killed in a car accident, Kaestel said, that family fell apart. Soon Kaestel stole a car and made his way to New Mexico, diverging from the straight and narrow path he’d almost traveled. “I know that when I first began to travel (hitchhiking) I’d go into a grocery store, make a sandwich, drink a milk, and eat a pear or something while I was inside,” Kaestel said. This progressed into taking funds by quietly approaching a cash register, opening it himself, taking a handful of cash. When he couldn’t hitch a ride, he decided it was easier to steal cars and siphon gas. Sometimes he broke into cars just for a warm place to sleep.

His years of wandering came to an end with the robbery at Senor Bob’s.

Kaestel and his companions had passed through Fort Smith at a dangerous time. The area was reeling from violence, with a string of brutal murders and a rapist on the loose. A month before their arrest, a killer executed a Fort Smith police detective, a young married couple and the wife’s coworker. In September 1980, a jewelry store owner and his daughter were gunned down at their Van Buren shop. And that November, a Fort Smith furniture store owner was shot to death behind the counter.

Then-prosecutor Ron Fields recalls winning seven consecutive capital murder cases in the years after Kaestel’s arrest. By some accounts, in the 1990s, Fields sent more people to death row than any other prosecutor in the country. “We’d had a number of cases along that timeframe,” Fields told The Daily Beast. “It just made us very concerned about manipulative men who had guns and didn’t hesitate to use them, and so that was probably something else that hurt him with the jury.”

“Now has he served enough time?” Fields added. “I haven’t opposed anything for many, many years. That’s up to the parole board and the governor's office as far as when he gets released, but I’m not jumping up and down saying, ‘keep him behind bars.’

“He did a lot more than what I would have expected from that crime. But again, it’s his mouth that got him where he’s at.”

Fields, 72, went to law school with Governor Hutchinson and later worked under him at the Drug Enforcement Agency, and followed him to the Department of Homeland Security, in the early 2000s. After his federal career came to a close, in 2005, Fields went into private practice as a criminal defense attorney.

Despite switching from prosecuting to defending the accused, Fields says time hasn’t changed his views of Kaestel’s trial or his life sentence. “We did the right thing back then,” Fields told The Daily Beast. “We handled the case exactly the way I would handle it tomorrow. The fact that he’s doing so much time is based on himself. I made an offer that would have not resulted in him serving this long.”

As a prosecutor, Fields said, he’d lie awake at night worrying about whether defendants he’d shown leniency would get out and hurt someone. “One of the primary considerations you have in a case is: what about next time?” he told us. Fields contends Kaestel had already been given a second chance: He was paroled in New Mexico for kidnapping and robbery years before getting busted in Fort Smith.

“I don’t think the system failed in this case,” Fields added. “I think there’s a good chance he would have gotten out and done more crimes.”

But advocates for Kaestel argue the system failed in allowing a jury to issue a life sentence, effectively without parole. Oliver, the prominent Republican operative, said Kaestel has “paid his penance beyond whatever crime he did or didn’t commit.”

“Part of America’s story is the story of grace and redemption, and he’s gone beyond that in a way,” Oliver told The Daily Beast. “So if we believe in the concept of grace and forgiveness, then we have to actually follow through on it. It can’t just be talking points, it can’t just be words from a pulpit, you have to put action behind it.”

“This man had his life stolen by the system,” McGowan told us, “It doesn’t show anything other than systemic insanity. There’s no logic.” The former actress and activist added, “I kind of feel like I’m trying to get my grandpa out of prison.”

Flom, the creator of the Wrongful Conviction podcast and an Innocence Project board member, compared the system that continues to punish reformed inmates like Kaestel to Les Misérables antagonist Inspector Javert, who relentlessly pursues Jean Valjean after he was imprisoned 19 years for stealing bread. “I don’t think anybody should rob anybody, but it was as benign as it could be, and the legal system treated it as if he had murdered someone or multiple people,” Flom told The Daily Beast.

Duda says Kaestel was someone with a rebellious streak, bereft of support or guidance from any family. He referred to Fields’ previous comments that Kaestel could have become the CEO of an airliner, given different circumstances. “While he thought he had the wind at his back, it was really in his face,” Duda said. “So, why is it so surprising that he fell into trouble? Sadly, he found himself in another institution for adults, also rife with abuse.

“It’s a miracle that he was able to self-correct—despite his circumstances and despite his environment. Because no one really ever believed in him. So, how do you believe in yourself? The man chose to look at himself, and change.”

Kaestel doesn’t claim that he’s innocent. Even in 1981, he had no hope that the jury would acquit. When he represented himself at trial—electing to, he says, because his public defender also represented his four alleged accomplices, who cut a deal to testify against him—he believed his punishment would fit the crime. “I was guilty,” Kaestel wrote to us. “I simply hoped and believed that jurors would do real justice… And I thought that a sentence of 10 years, or even 20 or 25 years would have been more than sufficient…”

Instead, jurors delivered a life sentence and a $15,000 fine. Under Arkansas state law, adults sentenced to life are ineligible for parole unless their sentence is commuted to a term of years by executive clemency. If their sentence is commuted, the prisoner would then be eligible for release on parole.

Craig Lambert, a post-conviction attorney in Little Rock who isn’t involved in Kaestel’s case, said capital murder is the only crime in Arkansas that carries life without parole. Other felonies, like first-degree murder and aggravated robbery, could bring a straight life sentence. But in both cases, a defendant isn’t eligible for parole. “That’s the law in Arkansas,” Lambert said. “Life with the possibility of parole sounds better than life without parole, but as a practical matter, they are the exact same thing.”

Arkansas is also among a handful of states where juries render both verdict and sentence. According to Kaestel, some jurors revealed post-conviction that they weren’t informed that all life sentences in the state—including those for non-capital crimes—are “without parole” and felt “tricked” into making their decision. (Fields said he never heard such a thing from jurors and told us, “If they didn’t want him to get life, they would have written down a figure. In this case, I think they were unanimous to get a life sentence.”)

Cummins Unit of the Arkansas Department of Corrections

Courtesy Kelly Duda

Fields painted Kaestel as the 29-year-old ringleader over a band of naive young travelers. Authorities alleged that Kaestel, who had a criminal record and served two years in New Mexico for robbery, directed his alleged accomplices to rob and steal as they drove across the country. During closing arguments, Fields told jurors: “The guy is educated. He is dangerous. He really is. He really is.”

“Ladies and gentlemen, do you really want this man back out on the street?” Fields warned, according to a transcript of the trial. “I want you to read the reports and think back on the evidence. Do you really want this man back out today? If you find him Not Guilty that’s what will happen. We will cut him loose today. Is that really what we want to put on this community or any other community, or do we have to protect all the people from Amarillo to here?”

During jury instructions, Fields urged the jurors to impose a maximum sentence. “How many times have you heard in the past people say, ‘I wonder why everybody is being so lenient with these type people,’” Fields said, according to a court transcript. “Well, ladies and gentlemen, I’m asking you not to be lenient.”

In an interview for this story, Fields described Kaestel and his group as a “Manson-like cult” and claimed Kaestel was articulate, manipulative and dominant. “He’s the guy who could’ve been a doctor or lawyer, he had all kinds of intelligence and talent—it somehow got warped,” Fields said, adding that Kaestel erred in handling his own defense and in being “incredibly assertive and cocksure of himself.”

Fields claims that both he and the judge tried to persuade Kaestel to get an attorney but “there was just no talking to him.” The former prosecutor said he also offered Kaestel a plea deal, and while he doesn’t remember specifics, believes he proposed a 35-year sentence.

Kaestel says he was forced to represent himself because “it was an unequivocal and unacceptable conflict of interest” for his alleged accomplices’ lawyer to also represent him. “So, I motioned the court for another lawyer,” Kaestel told The Daily Beast. “Then, when that motion was heard in court—another nearby attorney in the courtroom was asleep and reeked of alcohol, and it was my impression that he was the one about to be assigned to me—there on the spot, and I was not going to stand for that.”

Once he decided to represent himself, Kaestel wrote Fields, saying they both knew he was guilty; there was no need for a trial. He remembers clashing with Fields during a meeting, when the prosecutor offered him 35 years for aggravated robbery. (The jury’s verdict sheet indicated Kaestel could have been sentenced from 10 to 50 years, or life, since he had priors.) Kaestel believed Fields wanted to “trick me into surrendering 35 years of my life for that offense” and said he was “too immature to realize my mistake when I said some very direct and emotion-stirring things.” Fields “in turn vowed that he would give me a life sentence,” Kaestel recalled, “and I in turn spouted that he would do no such thing; a jury might but he was not going to impose a single day on me.”

Asked about Kaestel’s memory of their squabble, Fields said, “He would not have made me angry but I would have said, ‘You’re getting ready to talk yourself into a life sentence.’”

“I didn’t want people to get a larger sentence than I thought appropriate,” Fields said. “I didn’t want him to talk himself into the penitentiary for life.”

Kaestel based his defense on legal technicalities, alleging a lack of probable cause to search his friends’ car and pointing to a supposedly questionable police lineup during which Schluterman did not initially identify Kaestel. His strategy wasn’t to secure an acquittal, but to create a record for appellate review.

But Kaestel’s hopes of the courts reviewing his sentence were repeatedly dashed. He said the trial court never reviewed his sentence as disproportionate to punishments in similar cases; he couldn’t file a direct appeal because the Cummins Unit wouldn’t permit him access to typewriters when the court refused handwritten filings; and the U.S. Supreme Court returned his petition because he missed the filing deadline by one day. While he mailed his brief six weeks in advance, the U.S. Marshal Service accidentally misrouted his pleadings during security checks on incoming mail. He said the agency later issued him a letter of apology for the botched delivery.

“One of the most egregious injustices in my case is the fact that I also was never fairly and fully reviewed by any court in the country,” Kaestel said. “In spite of it all—no, I still do not regret having defended myself or fought all those years in the courts afterward. It was a conscious decision and I take every responsibility for it…

“Forty years and counting has certainly been a heavy price, wouldn’t you say?” Kaestel said. “I sometimes wonder how it would have turned out had things been different, but that’s actually silly to do.”

Kaestel has applied for clemency seven times since 1988, according to the parole board. The board determined his clemency application had merit in 1993, but ruled against him when he applied two years later. In the last decade, the board recommended his clemency three times, most recently in November 2020

A spokesman for Hutchinson said the governor has until Sept. 3 to decide on Kaestel’s latest bid for clemency, but his office does not comment on specific applications.

“I wish I could tell you this was an outlier,” Rachel Barkow, a New York University law professor and clemency expert, said of cases like Kaestel’s “They don’t all involve an offense with a toy gun, but the people that have perfect disciplinary records, they get education, they have not gotten into trouble, they’re clearly different people from when they committed their offense, and they still don’t get granted—that is like the dog bites man story in criminal justice.”

Kelly Duda was diving into the rabbit hole of a deadly scandal when he met Kaestel at the Cummins Unit prison, just outside of Grady, Arkansas. A friend who once worked at the maximum-security facility tipped Duda off to a tainted plasma program, and he was eager to investigate the bad blood. “I was curious and I felt like something bad was happening in my own backyard and I had a moral obligation to look into it,” Duda said.

Word spread among inmates, prison officials and politicos that Duda, a 33-year-old filmmaker, was probing the prison’s blood bank. Rumors swirled that he was a fed in disguise investigating the notorious lockup, or a double spy working for the prison itself. Little Rock attorney Jim Clouette contacted Duda on behalf of Kaestel, saying the inmate had information that could be helpful. “I didn’t just talk to any prisoner, because there’s a potential inherent trust issue,” Duda said. “You know what the prison is going to say: These are lawbreakers, how do you know they’re gonna tell the truth?”

In the 1980s and ’90s, the 16,000-acre prison—infamous for torture, forced unpaid farm labor, and prisoner “trusties” serving as the facility’s armed guards—was also running a blood bank that extracted plasma from prisoners, apparently without screening them for diseases. At the time, Bill Clinton was governor and a private firm run by his friend and fundraiser, Leonard Dunn, won a state contract to provide inmates’ medical care; the firm also mined prisoners’ blood, splitting the profits with the Department of Corrections.

Arkansas’ Cummins Unit, a maximum security prison, was at the center of the Arkansas prison system’s blood bank scandal. Kaestel became a key whistleblower.

Courtesy Kelly Duda

The prison blood, some of it tainted with HIV and Hepatitis C, was shipped to a Canadian broker which used the plasma to create blood products like Factor VIII, a blood-clotting protein deficient in hemophiliacs. Thousands of people across the world were infected and died from the blood sourced out of Arkansas, and the reverberations of the program continue today with at least one pending inquiry in the U.K. Investigations were also conducted in Japan and Canada, where victims sued their government in 1999 and later settled for $1.2 billion. Back then, their attorney vowed publicly to depose then-President Clinton and weighed naming him as a defendant in a future U.S. lawsuit, which never materialized. “We want accountability on the American side,” one victim said. “Why was this allowed to happen to us?” The Arkansas Department of Corrections doesn’t appear to ever have been sued or held accountable by the courts in connection to the scandal.

Kaestel was a key whistleblower in Duda’s 2005 documentary, Factor 8: The Arkansas Prison Blood Scandal. The film opens with Kaestel’s articulate Southern drawl: “There were several inmates here that were AIDS infected as opposed to merely HIV positive, and they would routinely bleed.” The prisoner, with gray hair and oversize Phil Donohue-style glasses, said that giving blood was inmates’ primary source of income. “I came to determine that it was literally a river of money flowing out of the blood bank and into our prison system here and it wended its way into every crack and crevice of this institution.”

Indeed, Kaestel told The Daily Beast he donated plasma himself “because that was about the only lawful way to make even a pittance of money—in the form of coupons they issued with which to purchase commissary,” until he discovered the program’s unsanitary operations.

Duda says that Kaestel and other prisoners put their own safety on the line for his film. “I was the novice,” said Duda, who is revisiting the Factor 8 corruption in a new investigative podcast called Darkansas. “I didn’t know what I was getting myself into. They did and they were willing to take the hits anyway.”

Around the same time, Kaestel also spoke to the Arkansas Democrat-Gazette about Cummins finally meeting national standards. “Although it is really tough for me to write this letter, particularly since I am currently trying to expose all the NEGATIVE things that are still going on here—the abuse, corruption and injustice—I must say that the accreditation guidelines have been substantially met,” he told the newspaper.

In 1970, a federal court ruled Arkansas’ prison system unconstitutional after Cummins inmates filed lawsuits alleging cruel and unusual punishment. In a chilling opinion, the court said “a sentence to the Arkansas Penitentiary today amounts to a banishment from civilized society to a dark and evil world.” The 1980 film Brubaker, starring Robert Redford, was based on a Cummins superintendent Tom Murton, who made national news after he accused “trusties” of abusing inmates and excavated the bodies of murdered prisoners on the farm.

Kaestel became an outspoken activist within this realm, filing a string of lawsuits and helping to launch a group called the Prison Reform Unity Project (PRUP) with a woman who believed her brother was killed by guards. He tried alerting local press to the contaminated plasma center, which he’d covered in the Long Line Writer in 1983, a story that earned him punitive isolation and got him fired before prison staff rewrote his story to “read like an obsequious PR piece.” He began working for local attorneys, including Clouette, while taking a correspondence paralegal course from 1988 through 1999.

“I happened to be working on the visitation yard when an attorney struck up a conversation with me,” Kaestel says of Clouette. “One thing led to another and I guess he was impressed enough to propose that I write a couple of sample briefs for him—and if it worked out, I could do piecemeal work for him. Well, I quickly won a handful of cases for him and his firm, and word spread. Over the years other attorneys contacted me now and then.” Clouette told The Daily Beast that in the ’90s, he was prepared to offer Kaestel a job at his firm starting at $50,000 a year and help him find housing if clemency was granted. “The whole time I’ve known him I’ve never considered him a danger at all,” said Clouette, 74. “Fortunately he had the mental ability and the drive to actually do something different than just sit down there and waste it.”

Gayla Hooten, Clouette’s former legal assistant, told The Daily Beast that Clouette was a fair and likeable attorney with a heavy caseload and good reputation, enough for a federal judge to hire him to represent a son who’d gotten into trouble. Kaestel did research and wrote briefings for Clouette’s post-conviction cases when the lawyer was too busy.

She became close to Kaestel and got the feeling she was one of his only friends. In the penitentiary, she said, Kaestel wanted to avoid the criminal influence around him. “He’s pretty much a loner,” Hooten said. “He didn’t have a lot of friends, didn’t want a lot of friends in prison. Not that he was totally anti-social. He just didn’t want to become institutionalized. I think he was his own person and wanted to stay that way.”

“He is rehabilitated,” Hooten said. “He was young, I mean that was in his twenties, and he did have some juvenile problems, acting out, rebelling. I think he was just rebelling against life. He had no place to turn, he had no direction, he had no love.”

Hooten lost touch with Kaestel after he was transferred to the Beehive State because of what prison officials cited as “noncompliance with the Arkansas system.” Multiple people close to Kaestel over the years say the move was retaliation for speaking in Duda’s film. “The ADC had a prisoner that they wanted to get out of Arkansas and they asked Utah to accept him,” Hooten concluded.

While Duda believes Kaestel is a political prisoner, a ceaseless reformer Arkansas officials want out of their hair, Kaestel says, “I cannot convince myself that someone may be pulling strings behind the scenes to vindictively keep me locked up.”

Kelly Duda, an independent filmmaker, met Kaestel while investigating the Arkansas prison system’s blood bank scandal, which infected and killed thousands of people across the globe.

Courtesy Kelly Duda

“If there is some political element to any of it, I think that it is because I am a ‘nobody’ in the eyes of politicians, being that I have no family who can vote, and no ties to Arkansas.”

Still, Kaestel remained a model prisoner in Utah, taking enough college courses to be six or fewer credits short of completing bachelor’s degrees in psychology, history, sociology, English and other subjects. One educator who worked with Kaestel remembers him as highly intelligent and honest and told us: “As far as I’m concerned, they [the state] just said he’s going to die and rot in prison and he doesn’t deserve to. Period.”

Kaestel said he is grateful for his education and self-improvement opportunities over the decades, and “if none existed I tried to create them, not only for myself but for other prisoners as well.” He added, “I’m just geared that way; inquisitive, determined, and wanting now to make it through life without bumping into any more walls than I already have; and to do what good I can to alleviate others’ misery and disillusionments.”

Through a prison program, Kaestel teaches astronomy/cosmology, saying he’s “hoping to get the guys to use some of their imagination exploring something a little bigger than their ‘hoods,’ housing units, or the prison compound!”

“Why not send them into a virtually limitless universe to ponder life’s marvels. You know?”

As Inmate No. 076784, Kaestel tries to enjoy something “different” each day behind bars. He longs to get out into the fresh air, even to his unit’s concrete-walled side yard covered from 20 feet above with a metal grate. “So, at least the sky is visible,” Kaestel said.

He wakes around 4 a.m., then ponders in the morning’s quiet. Two hours later, his prison wing holds a brief meeting before breakfast, after which he watches the news. Kaestel lives in an esteemed dormitory section called STRIVE (Success Through Responsibility, Integrity, Values & Effort), where residents must work 40 hours a week or take classes.

At 7 a.m., Kaestel starts his shift at the prison’s 25,000-book main library, where he’ll stay until 3:30 p.m. He spends the rest of the afternoon writing, usually on issues of faith.

For Kaestel, everything changed when he was put away at age 29. “Had Christian faith not dawned in my life back in 1981 when I was convicted of this offense,” he said, “I doubtlessly would have become anything but a model prisoner.”

“It is and has been the source of my growth and maturity as a man,” Kaestel added. “Without faith I would never have sublimated my ‘in your face’ attitude in other than more destructive and self-destructive ways. I would likely be dead now.” Kaestel is hesitant to discuss this transformation, however, especially because many inmates are perceived to “find Jesus when they go in and leave him at the door when they leave.”

Should he be released this time, Kaestel hopes to find work as a paralegal and continue his writing. “It is my deepest hope that if I am released I will have the opportunity to finish all that my heart determines that I should write,” he said. “I am 70 years old now so that may well complicate things as far as employment, a place to live, and the like.”

Frazier was his last visitor several years ago. The former City Weekly scribe said he routinely chased down leads, even when they seemed too crazy to be true. “And with the case of Rolf,” Frazier said, “you find out it is all true. The horror of his case. And the way he was sentenced, and all the time that he served.”

Like all who encounter Kaestel, Frazier quickly grasped the prisoner was intelligent and a bit of a reporter himself. Kaestel has “a very strong bullshit sensor, even as an imprisoned person,” said Frazier, who now runs Fisher Brewing Company in Salt Lake City.

“Rolf will tell you if you meet him or correspond with him, that he made mistakes in his life, that he did in fact rob Bob’s Taco Hut many years ago. He shouldn’t have done that but he doesn’t deny that he was a bad guy and made mistakes in his life.”

Frazier said he’s been haunted by Kaestel’s case since meeting him in 2014. “Rolf has been stored away in my state now for the past 20 years and I pay for it,” Frazier said. “I think the taxpayers of Utah, the taxpayers of this country and Arkansas, our hands are dirty. I feel like people should feel like we’re a part of this injustice.”

When he was last denied clemency in late 2015, Kaestel wrote Frazier, saying, “If anyone indeed does believe that I have suffered unjustly, then be absolutely assured that there are tens if not hundreds of thousands of prisoners in these United States who are much more unjustly punished to extremes than was I, and who are much more worthy of your sympathies, compassion and support.”

He followed up with a message posted on a Facebook page called “Free Rolf Kaestel.” After Hutchinson’s decision, he thanked people for supporting his request for a commutation “even though my case is not one of innocence or wrongful conviction.”

“I was guilty of my crime and in my teens/early adult life, my conduct was inexcusable. However, I did change and your willingness to forgive was likewise a moving and precious thing,” Kaestel wrote, adding, “Please do understand that I am fine and will continue in my undaunted efforts to make a positive impact in the world, both here within prison and to some extent outside.”

“God bless you all. Thank you for having cared.”

======

No comments:

Post a Comment