This article was published online on May 4, 2021.

My father died this spring. Right up until he went into the hospital, at age 88, he lived alone in a small houseboat at the end of a long pier, bare of conventional creature comforts but filled with his books and maps and hiking gear. My brother and I had worried: “Dad, you could have a heart attack and fall in the lake.” Better that than give up his freedom, he’d said. To other people, his ascetic life might not have looked like freedom. It might’ve looked like emptiness. His life seemed to be made up of things he didn’t have. But to him, the not-having was the same thing as his freedom.

I sat by my father’s hospital bed for two months. As he slept, he gripped my left hand and I held a book in my right. Toward the end of my vigil, I read new novels by Rachel Cusk and Jhumpa Lahiri. The protagonists of both books have built lives that are full of refusals, as my father did. But there is one important difference—these first-person narrators are women, and they wear their refusals awkwardly; my dad wore his with a sovereign dignity. Refusal, like so much else, turns out to be the prerogative of men. The narrator of Cusk’s Second Place, identified only as M, says it plainly, addressing a male painter who is identified as L: “ ‘You’ve always pleased yourself,’ I said, somewhat bitterly, because it did seem to me that that was what he had done, and what most men did.” M, by contrast, struggles to please herself, apart from others.

Second Place is a strange novel. The publisher calls it a fable, and perhaps it is, in the sense that many of Cusk’s books can be read as fables of female dissatisfaction. Drawing on the observational spareness of her celebrated Outline trilogy and the eccentric vigor of her earlier work, she powerfully blends evocations of personal turmoil with ruminations on art, truth, freedom, the will, men and women, and more.

Cusk signals a turn away from Outline’s realism at the start, as M recounts a cryptic meeting with the devil on a train trip years earlier, heading “back to a home I thought of with secret dread” after an unsettling visit to Paris. A young mother, she has just been transported by the paintings she sees at a major retrospective of L’s work. The hideous devil is gabbling nonsense and fondling a doll-like girl. He seems to be taunting M to try to stop his antics, and leaves her feeling that she’s failed her “moral duty as a self,” not that she knows what that duty is.

From the January/February 2017 issue: Ruth Franklin on Rachel Cusk’s fiction

After a long period of emotional devastation—devastation spurred by her encounter with the devil yet only hinted at—M has finally landed in a rural idyll on the shores of a marsh in an unspecified country. There she shares a home with Tony, a taciturn fellow who seems content with his lot in life—decidedly unlike M. From their remote outpost, she writes a letter to L, whom she has never ceased to think of and admire deeply. She invites him to take up residence in a kind of guesthouse on their marsh property, amid what appears to be our current pandemic.

L’s arrival at the “second place,” as M and Tony call it, brings about a series of reversals and revelations, each of which exposes to M a further unpleasant truth about herself and “how lonely and washed up” she feels, plagued by “a tormenting scent of freedom,” yet unable to do much of anything. Can L, she needs to know, “release me into creative action”? The tension between M and L, between female and male, between domesticity and art, between restraint and abandon fuels the book. M clings to the few things she has found that make her feel safe and in control—Tony, her now-grown daughter, the marsh—even as she hears an “inchoate call out of some mystery or void,” which she associates with L.

L, meanwhile, is suffering his own setback—his work is going out of fashion. When L complains about his reduced circumstances, M explains, “Not to have been born in a woman’s body was a piece of luck in the first place: he couldn’t see his own freedom because he couldn’t conceive of how elementally it might have been denied him.” M’s escapes from her disapproving first husband and from the “fleshliness” of the parent-child bond have plainly been ordeals. And her struggles to absorb some of L’s power, evoked with great subtlety by Cusk, ultimately come to naught. “That’s all I’ve managed as far as freedom is concerned, to get rid of the people and the things I don’t like” is her rueful verdict. “After that, there isn’t all that much left!”

In a short note at the end of the book, Cusk reveals that the novel “owes a debt” to Lorenzo in Taos, a memoir by the patron of the arts Mabel Dodge Luhan (M) about a long and difficult visit from D. H. Lawrence (L) in the 1920s. “Intended as a tribute to her spirit,” Cusk’s transmutation of Luhan’s book nods to a long lineage: The predicament of the frustrated female artist orbiting the male was haunting 100 years ago and still is today. In order to create, the woman who sets out to make art knows that she must refuse something, some aspect of her femaleness. Second Place lets us listen as one such woman tries to describe what happens to her—in her mind and her body, alone and in the company of others—as she finds herself stymied.

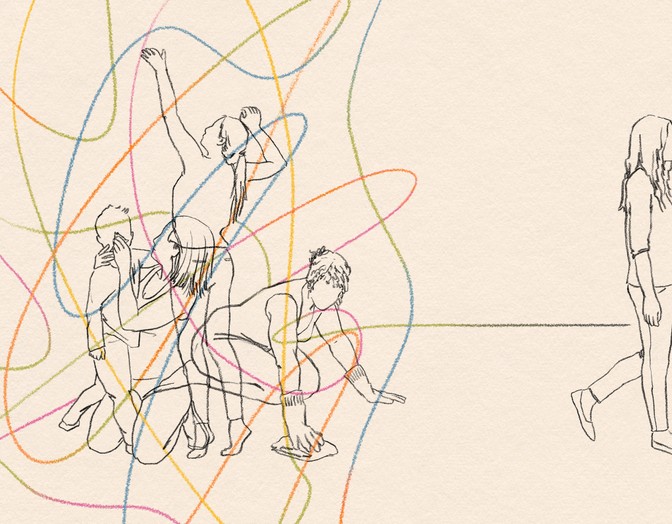

The unnamed narrator of Jhumpa Lahiri’s Whereabouts—the first novel that Lahiri has composed in Italian and then translated into English—practices a starker form of refusal, rendered in short, journal-like fragments so strongly and rightly voiced that other books sound wrong when you turn to them. She lacks M’s fierce yearning for creativity, yet very much like M, she keeps her social circle and activities limited. “I dislike waking up and feeling pushed inevitably forward. But today, Saturday, I don’t have to leave the house. I can wake up and not have to get up. There’s nothing better.” She and Cusk’s M make a small sisterhood of women staring into space. It’s as though only in inactive solitude can they listen to their minds, register the ineffable, and, perhaps, prod at the feeling that freedom eludes them. (Perhaps the sisterhood is not so small.)

Yet she, like M, can’t decide just how willed her retreat really is, and does her own quieter form of soul-wrestling. Living alone in a spare apartment, she takes walks by herself. At times she finds moments of quiet transcendence in her solitude: “As I eat it,” she reflects, sitting outside with a sandwich, “as my body bakes in the sun that pours down on my neighborhood, each bite, feeling sacred, reminds me that I’m not forsaken.” Other times, her solitude makes her fussy. A friend’s child leaves a pen mark on her sofa:

The line is like a long strand of hair, innocuous, intolerable. A line that drifts and drifts. I can’t rub it away with my finger. Nothing I do to try to lift it works. I buy cushions, a blanket to hide it. But they’re not a solution, the cushions move around and the blanket slips down. I read on the armchair now.

In this emptiness, subdued images loom with outsize power.

The way she inhabits her isolation recalls Barbara Pym’s Excellent Women, another luminous portrait of a chosen withdrawal. (In places, Lahiri’s book also calls to mind the sourer loneliness evoked in the poetry of Pym’s friend Philip Larkin.) Pym’s narrator is offered various escapes from her solitude, but opts to mete out her time in her own way. The glory of the book lies in her dominion over her own hours. Lahiri’s narrator, too, says solitude “demands a precise assessment of time, I’ve always understood this. It’s like the money in your wallet: you have to know how much time you need to kill, how much to spend before dinner, what’s left over before going to bed.” There’s a sadness here—but money is, after all, valuable. Lahiri’s narrator is spending her hours in the way she and only she sees fit.

The effect is of someone making her way carefully through the world, always aware of the void below, well practiced in navigating with a command that both is and isn’t what it seems. Lahiri highlights this theme of precariousness as her narrator thinks back on a girlhood game, popular among her peers, of hopping from tree stump to tree stump:

It now occurs to me that I was as tenacious as I was timid. I never protested, I did what they did, that is, I clambered up, I hesitated, and then I strode across, afraid each time that the empty space between the stumps would swallow me up, terrified each time that I would fall, even though I never did.

She envies the “brazen strides” of the other girls, yet also prizes her outsider status.

Both of these books might sound bloodless, and yes, Cusk’s and Lahiri’s narrators seem to have freed themselves of the familiar forms of wanting. That hasn’t drained them of will, though. They are anything but passive or pain-averse, or fragile. They are desperate, and their refusals feel like a groping yet determined effort at survival—survival on terms they need to discover, define, understand. They don’t know what to do, but they feel they know what not to do: be a woman like other women.

For her whole life, Lahiri’s narrator has watched her mother give way to her father’s wishes. Cusk’s M has come to resist the demands of upkeep, of caretaking: “the feeling that my life has entailed too many practical tasks, so that if I add even one more to the total, the balance will be tipped and I will have to admit I have failed to live as I have always wished to.” Cusk and Lahiri know that motherhood and domesticity will eat you alive. They don’t know how to fix that, but their narrators know that a woman who wishes to be free has to not do a lot of things.

In a memorable scene in Cusk’s Transit, the second in her Outline trilogy, she captures the enchantment and the entrapment of domesticity. Her narrator, Faye, attends a dinner party at her cousin’s house in the country, complete with candles, music, pretty children, bejeweled women, all sheltered in a “long low farmhouse.” What could be lovelier? Yet before the evening is through, mayhem has set in and everyone is behaving very badly. Faye can’t get away fast enough the next morning. As she escapes the house, she says, “I felt change far beneath me, moving deep beneath the surface of things, like the plates of the earth blindly moving in the black traces.” Earth-shaking: That’s the daunting scale of transformation entailed—or at least desired. (Faye is well aware that her own children await her at home.)

I—and these novels confirm I’m not alone—also want some other life that can be lived by some alternative version of myself: unscripted, maybe lonely and uncomfortable. And that life starts with refusal. This in-between state is where the narrators of Second Place and Whereabouts exist. They are saying the essential no. For this reader at least, that’s a thrilling spectacle—and a yes, Cusk suggests, is perhaps hidden in there. “Might it be true,” M wonders late in the novel, as she considers her daughter’s future, “that half of freedom is the willingness to take it when it’s offered?”

My father’s freedom never seemed like it could be mine. I was raised to be like my mother, to please other people. After my father died, I walked onto his houseboat and looked around at the light streaming through the windows; the walls of books; the few, chosen objects. I saw, too, the tight quarters, the galley kitchen, space enough to fulfill the needs of only one person. I had struggled my whole life to become my mother, but suddenly, my children almost grown, I wondered whether I could become my father instead. Could I live here? Could I be free and sovereign? Could I simply … refuse?

This article appears in the June 2021 print edition with the headline “The Power of Refusal.”

No comments:

Post a Comment