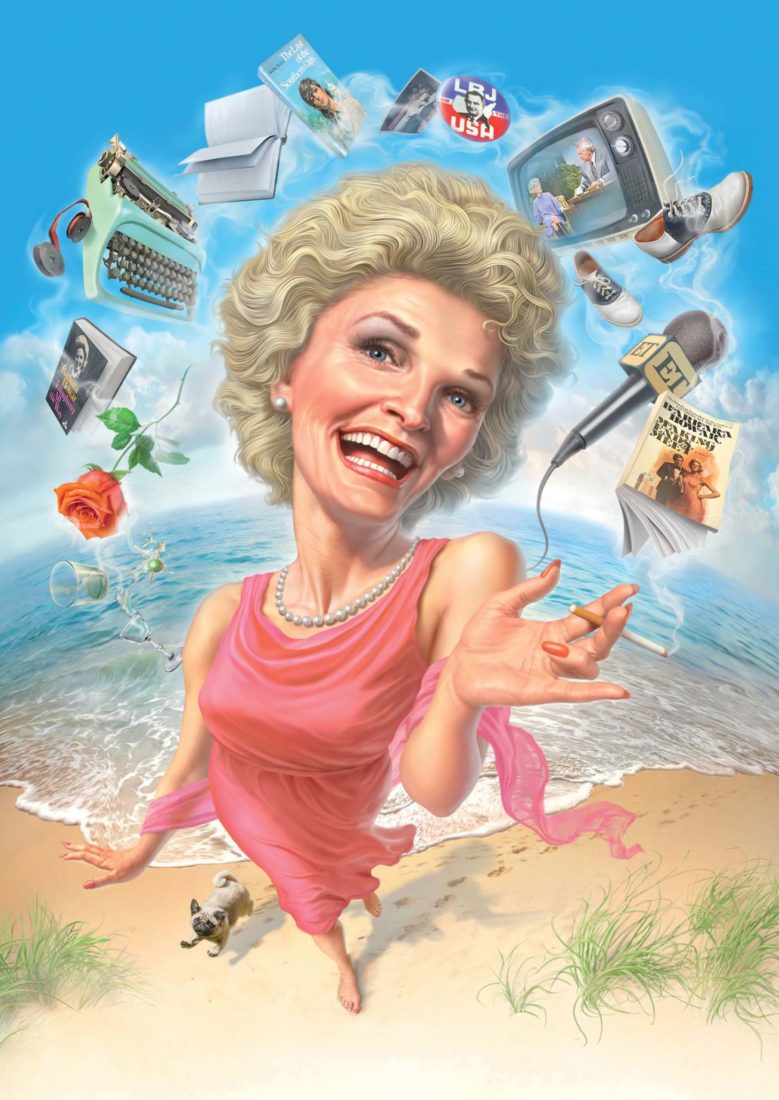

White House insider. Socialite. Best-selling author. Pioneering broadcaster. A torrid romance with Willie Morris. Barbara Howar of North Carolina did it all, living a life most of us can only imagine before eventually giving the finger to the spotlight. We tracked down one of the great—and largely overlooked—Southern heroines

PHOTO: MARK FREDRICKSON

“I don’t do lunch.”

The candor was on point but still surprising for a woman with a reputation cemented as a “hostess” in the nation’s capital. That was Barbara Howar’s response to our first efforts to meet her, in 2003.

We sought out Howar because she, like each of us, was a North Carolina transplant to California. Decades earlier, she’d lived in Washington, D.C., where she became the focus of sensational media coverage. Magazine and newspaper images showed her doing the Frug in a miniskirt, waving to a photographer from Life while zipping through city streets on a scooter, and dancing with President Lyndon B. Johnson at his inaugural ball. She appeared to be the consummate Potomac party girl.

By the mid-1970s, “Barbara Howar from Washington” had become one of Johnny Carson’s favorite guests. During the eighties, you could hear her unmistakable Tar Heel lilt on Entertainment Tonight, where she was a senior correspondent. When we first called her, she was working for Norman Lear, creator of such iconic TV hits as All in the Family and The Jeffersons, searching for properties for him to produce.

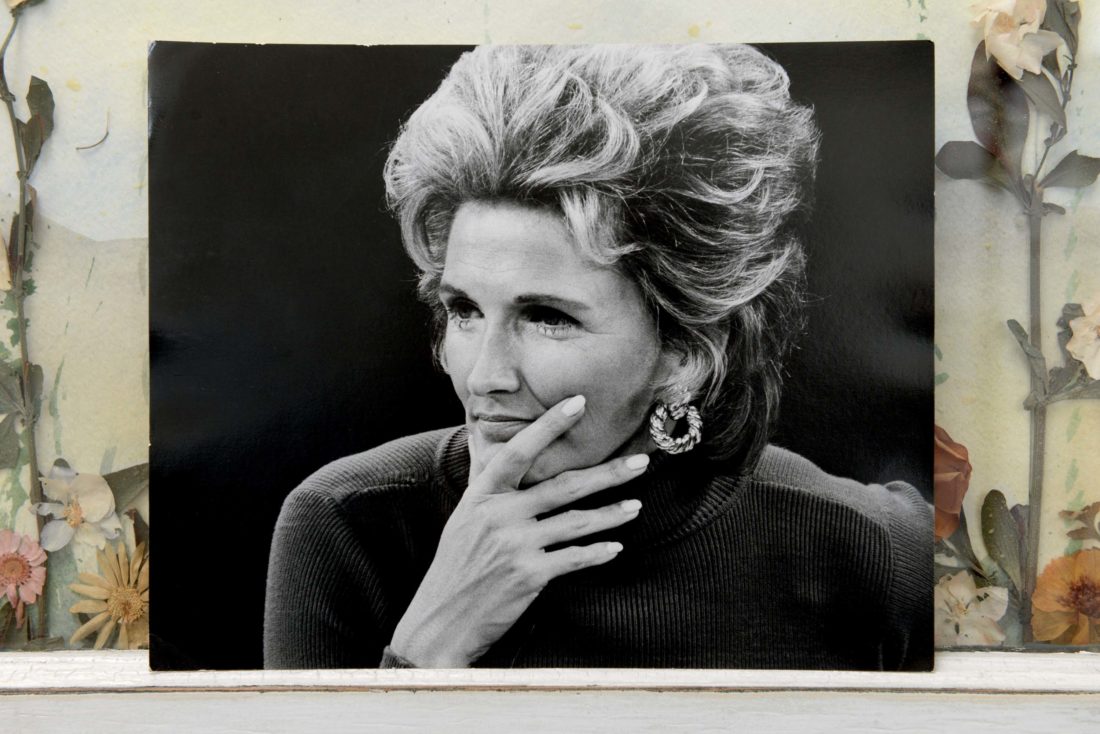

PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE HOWAR FAMILY

Howar during filming of the Joyce and Barbara show in 1971.

Howar’s past also held intriguing literary allure. In addition to writing two best sellers of her own, Laughing All the Way and Making Ends Meet, she was rumored to have inspired the heroine in Willie Morris’s first novel, The Last of the Southern Girls, published in 1973. Following the success of his 1967 memoir, North toward Home, Morris had been named the youngest ever editor in chief at Harper’s, and he would go on to become such a treasured Southern writer that when he died in 1999, he lay in state in the Old Capitol rotunda in Jackson, Mississippi.

The novel chronicles a debutante from Arkansas named Carol Hollywell. Against the backdrop of national unrest, she has an ill-fated romance with an idealistic politician from the South as she tries to mentor him into greatness. Morris writes of Carol: “An aura of romance and beauty surrounded her, there was a rare electricity to her movements, she seemed touched with gold, and people would stare at her in the streets or in the restaurants, not just because of this radiance, but something more: the good juices and spirits of life which encompassed her, her elegance and proud defiance.”

What would it take to inspire such ardor in Willie Morris? The media portrayed Howar as somewhere between a “socialite” and an “enfant terrible.” Could she really be Carol Hollywell? We wanted to know.

“I don’t do lunch” would remain her response for almost a decade.

Her conservative father, known as Big O, didn’t approve of higher education for women, so he sent her to Holton-Arms, at the time a finishing school in Washington, D.C., that she later described as “a good place to store girls for a few years before marrying them off.” She fell in love with the very city her father considered a “dung heap,” but her dream of conquering Washington would have to wait. First, she had to go back home to perform that “final tribal rite of a nice Southern girl”: becoming a debutante. It was perhaps the last time she did what was expected of her.

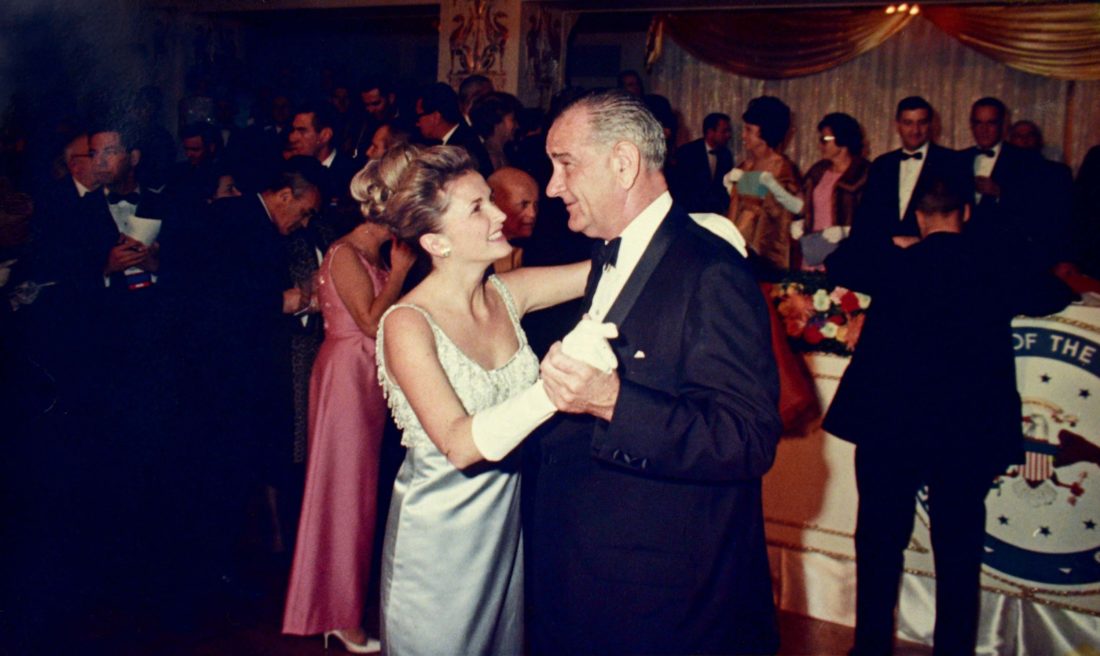

PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE HOWAR FAMILY

Dancing with President Lyndon B. Johnson at his inaugural ball in 1965.

While her girlfriends were adding “Mrs.” to their names and joining the Junior League, Barbara chased her own dreams. She wanted to be a real-life Brenda Starr, heroine reporter. Thumbing her nose at her father’s politics, she got a job at the liberal Raleigh Times, where she had to get up “at the crotch of dawn to get to work.” Despite her getting assigned menial tasks and occasionally writing florid articles for the society pages, the nonstop action and cigar smoke of the all-male newsroom enthralled her. She took particular delight in their creative profanity.

She left North Carolina on New Year’s Day, 1957, to make her way in Washington, D.C., with nothing but a few traveler’s checks in her pocket. Her father offered her no financial support but did launch a parting salvo: “The higher a monkey climbs, the more it shows its ass.” Barbara’s antics in the nation’s capital would suggest she took those words as a personal challenge.

Soon after arriving in D.C., Barbara, then twenty-four, was already ascending Washington social circles when she married Edmond Howar (pronounced like “flower”), a first-generation Arab American, in 1958—an interracial, interfaith match that shocked many, including her family back in Raleigh. She found great satisfaction in just how much Ed differed from her father. The wealthy son of a self-made millionaire famous for developing Washington’s first mosque, he was learning his father’s construction business. Handsome and charming, he had the patience and deep pockets to let Barbara shine—so much so that he became known around town as “Barbara Howar’s husband.” The couple settled into one of the Howar family’s luxury properties in Georgetown and had two children, Bader and Edmond Jr.

When President Johnson put out a call for “untapped talent” to assist with his reelection, Barbara was poised to answer. She worked the 1964 Democratic National Convention as one of the Ladies for Lyndon, most of whom were daughters or wives of Johnson insiders. She charmed the guests with courtesy and canapés as a hostess in the President’s Club Lounge, which served big-money donors. Drafted into the fall campaign, Howar donned a full-skirted “Johnson Blue” dress and boarded the Lady Bird Special, a train that sent the First Lady and her attendants on a whistle-stop tour of eight Southern states. Her jobs—shellacking Mrs. Johnson’s hair and fluffing the dresses of the Johnson daughters—gave her intimate proximity to the First Family. She performed the song “Hello, Lyndon” maybe a hundred times a day and after the election joked, “I’m convinced that’s how LBJ almost lost the South.”

But it was her position as coordinator of the inaugural ball sites that distinguished her. She laughed at a caption in the Washington Post: “Barbara Howar to Handle Johnson-Humphrey Balls.” She was granted an office in the White House, and she danced with LBJ himself on the night of his inauguration. There she was, Barbara Dearing Howar from Raleigh, dancing with the president! For fifteen minutes! The First Lady had to break in.

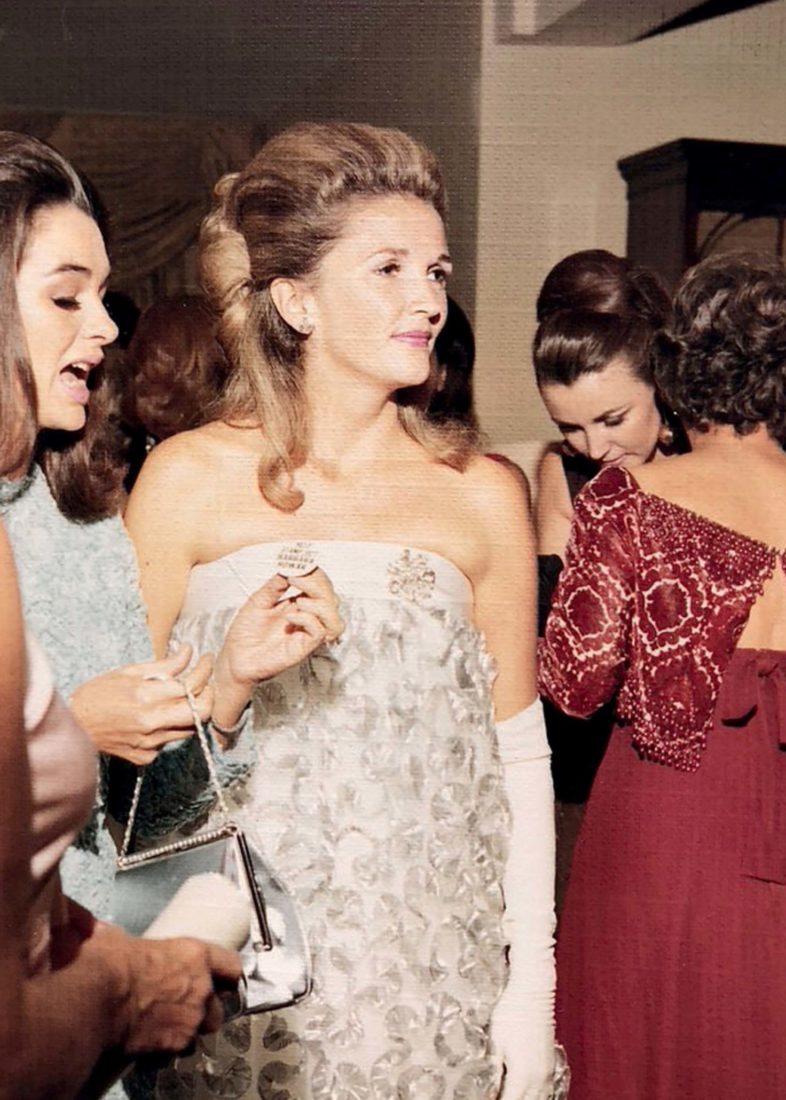

PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE HOWAR FAMILY

Howar (second from right) on the campaign trail as one of the Ladies for Lyndon.

Less than a year later, Johnson was under siege—he’d pushed the country deeper into the Vietnam War, and demonstrations met him wherever he went. For a president concerned about his image and aware of his White House lying in the shadow of the Kennedys’ Camelot, Howar had provided a welcome touch of glamour. But as she got invited to family dinners in the private quarters, became a regular at Johnson family home movie nights, and grew more essential to his daughters, she attracted more attention from the press, and jealousy from the staff, some of whom launched a campaign to oust her. They circulated a rumor that a magazine would be printing an exposé about Barbara, an affair she’d had two years earlier, and the Johnsons themselves. The mere threat of negative publicity made her a liability to the embattled president. Overnight, the engagement party she’d planned for First Daughter Luci on the roof of the Hotel Washington was canceled. And so was Barbara. As if the First Family freezing her out weren’t scandalous enough, what she did in response made her infamous.

After she was tossed out of the Johnsons’ inner circle in 1966, conventional wisdom dictated that Howar should slink away and, after an appropriate amount of time and wound licking, perhaps one day reemerge on the social scene. Ever the contrarian, she kept a high profile and embraced her own outrageousness. She became the youngest ever chair of the International Ball, a benefit to raise funds for a children’s hospital, and her friends handed out STAMP OUT BARBARA HOWAR buttons to wear at the event. She declined to wear one herself, saying, “I do enough on my own to stamp out Barbara Howar.”

At home she was restless and had been for much of her marriage. She engaged in a second affair, this one with a White House aide. She told Ed she wanted a divorce and even told him about the new man in her life. Believing things would proceed cordially, she traveled to the Caribbean with her lover, unaware she was being watched.

Ed had employed D.C. private eye Dick Bast, the “Mike Hammer of politics,” to follow Barbara. Bast tracked her to the hotel and wired the room for sound. “At such time as we hear that sexual relations are taking place, then myself and a photographer would go into the bedroom and take the photographic evidence,” Bast explained to the writer Taylor Branch in a 1976 story for Esquire. He recalled storming in on the couple: “I threw the guy on the floor and called Howar a cheap whore.” Barbara herself told Branch, “It was like being accosted on a street corner by the Boston Strangler.”

WHY L.B.J. DROPPED ME, read the cover line on the April 1968 Ladies’ Home Journal. For fifty cents a copy, it promised that “a beautiful Washington hostess” would tell “the full tale, gossip and all.” Howar’s story did even more. In a magazine spread featuring a glamorous photo of her dancing with LBJ and another of her cheekily standing outside the White House gates, she detailed everything from the Johnson daughters’ dress sizes to their father’s eating habits. She shared endearing stories about her time with the First Daughters, including their Secret Service code names (Luci was Venus, Lynda was Velvet), along with the conniving of staff members and rivals. For a president who valued loyalty and secrecy, Howar annihilated both.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE HOWAR FAMILY

Howar at the International Ball in Washington, D.C., in 1966.

When the article hit the stands, it launched her back onto the national stage. She became a modern-day Hester Prynne, using her scarlet letter as a calling card. What she wrote marked the beginning of what the feminist author Erica Jong would later call the best and most honest account to come out of the Johnson years, “a blast of clean air.” Howar took her saga on the road and landed in the red-hot center of America—The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson.

That summer, Washington’s Channel 5 hired Howar to deliver commentaries for the 10 O’Clock News, which led to her cohosting live coverage of Richard M. Nixon’s inauguration. The station’s general manager was so impressed with her no-holds-barred interview style that he put her on the midday news-and-talk show Panorama. Her cohost was a twenty-eight-year-old Maury Povich.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE HOWAR FAMILY

Chatting with Washington Post columnist Art Buchwald in Georgetown.

“With Barbara, there was no filter,” Povich recalled with a laugh. “She was irrepressible. She would say things like, ‘You know, I have such a smart dog that he only pees on the New York Times.’ And I would reply, ‘I guess that’s a form of yellow journalism.’ We had a great repartee. And she would also ask congressmen and senators questions they wouldn’t get from anybody else. She was the most refreshing personality on television in those days.”

Upset that her salary amounted to a fraction of that of her male counterparts, Howar left Panorama and was soon headlining Joyce and Barbara: For Adults Only, along with Joyce Susskind. The show seemed to usher in a new era for women on TV. On their debut, Susskind asked their guest, screen legend Bette Davis, “Do you feel you made being a bitch stylish?” Howar interjected, “She certainly gave me my start.” It got canceled after only a short run. Howar said she was meant to play second fiddle to Susskind, and that was “an instrument I had no ear for.” So she started writing again. Her story. What she witnessed in Washington. For twelve to eighteen hours a day, she tapped away at her typewriter.

“She would make dinner for me and Bader, and we would sit at the table,” her son, Edmond, recalled. “Mom did her motherly duties. But during the time of writing, it was the book only.”

G.P. Putnam’s Sons advanced Howar $15,000, but when she turned in the first half of the manuscript, executives demanded she pay them back: “We want Washington gossip, not Howar’s story.” She was devastated. Her agent, Sterling Lord, advised her to continue working, offering to lend her some money. Her oldest sister, Puddin, and her brother-in-law, Sarge, took out a second mortgage on their house to provide some income. “Keep your ass in gear,” Sarge said. To get some focus, Howar found a rental cottage in the Hamptons and kept writing.

The friendship grew. We persuaded her to come to dinner with other Southerners in Los Angeles, and she loved every minute of it. She extended us an invitation to be her dates to a party at Norman Lear’s in Mandeville Canyon. It was no surprise to see that she was one of his favorite people.

We became acquainted with her children, Bader and Edmond. As one might suspect, Howar hadn’t exactly been a traditional mother. Growing up, they had TVs in their rooms, and she encouraged them to hang out with the adults. And then there was Howar’s “sailor’s mouth.” “My friends would come over just to hear it,” Bader said. “Mom would be making supper, and they’d get me off to the side. ‘When is your mom gonna cuss?’ So I would drop a jar of mayonnaise or something on purpose, and Mom would let the expletives fly.”

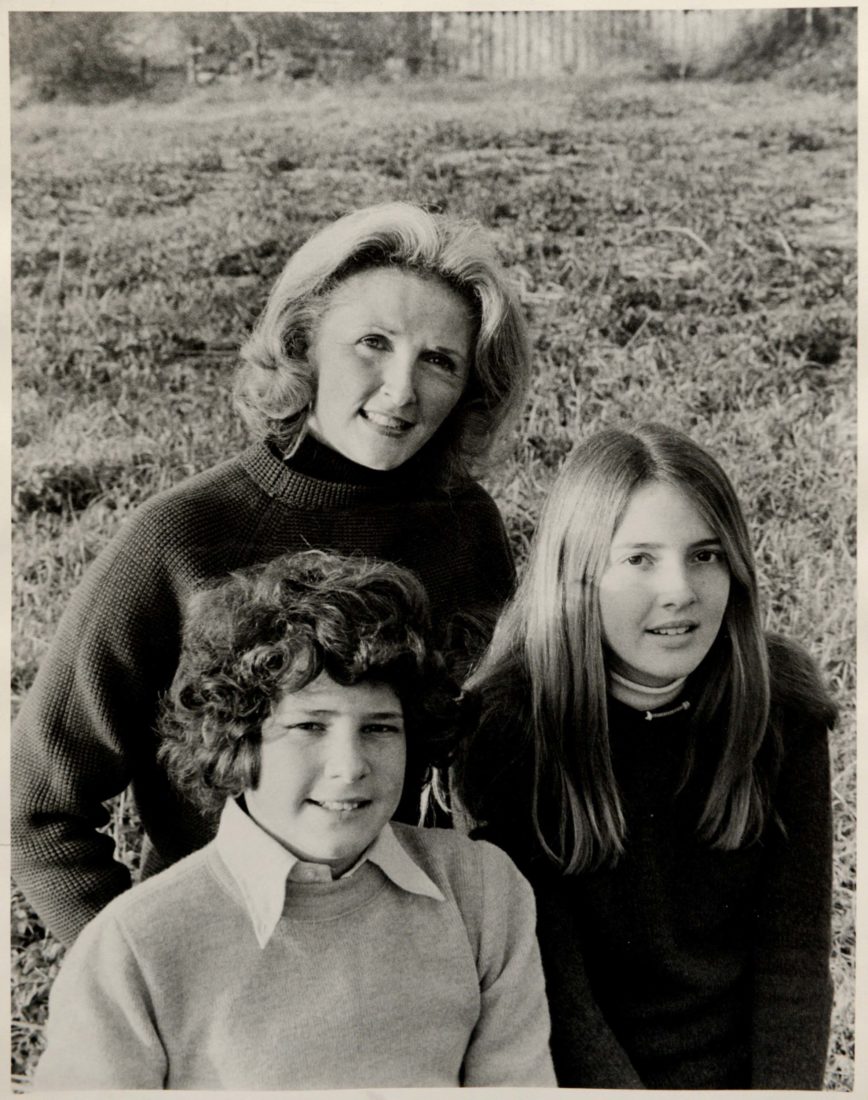

PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE HOWAR FAMILY

Howar with her children, Edmond Jr. and Bader, in 1975.

Bader said her mom was hard on them but bolstered them too—she wanted to give them a sense of independence. She wasn’t usually the kind to help with their homework, except for one memorable occasion. “In ninth grade I was out smoking dope with my friends,” Bader recalled. “When I came back in, there was Bob Woodward, Carl Bernstein, Nora Ephron, and Mom. They were all pretty deep in their Scotch. I told them I had to go to my room to write a basic composition for class. Well, they all got into a big competition and they wrote my homework for me, a group effort. All these great writers. I handed it in—and got it back from the teacher with a C minus.”

When he was eighteen months old, Edmond was diagnosed with spinal meningitis and struggled with hearing as a result. “Mom taught me how to read lips,” he said. “She would say, ‘Look at my face,’ and touch her lips and indicate for me to follow her mannerisms. Ninety percent of the time these days I’m reading lips and it’s because of her.” She gave him much more independence than most kids with hearing loss might have had. “She didn’t want me to be held back or shy. She wanted me to have confidence, to live life.”

Howar had written two unpublished manuscripts in L.A., Still Laughing and Better Than Before. In one of the more touching anecdotes about Edmond, she recalled watching over him during the early days of his life-and-death battle in the hospital. Although he couldn’t hear her, she told him over and over how much she loved him. She put his limp body in a stroller and wheeled him up and down the corridors, saying, “We are very brave, Edmond, and we will soon go voom-voom every day.”

Not long after our lunch, at Howar’s apartment in an old house on Doheny Drive in West Hollywood, a bourbon provided us the courage to ask her a question that had long been on our minds. “Did you read The Last of the Southern Girls?” She changed the subject with the finesse of a master politician. The topic of Willie Morris was not a casual one. But she did mention that she kept notebooks and a collection of letters. “One day I should show them to you.”

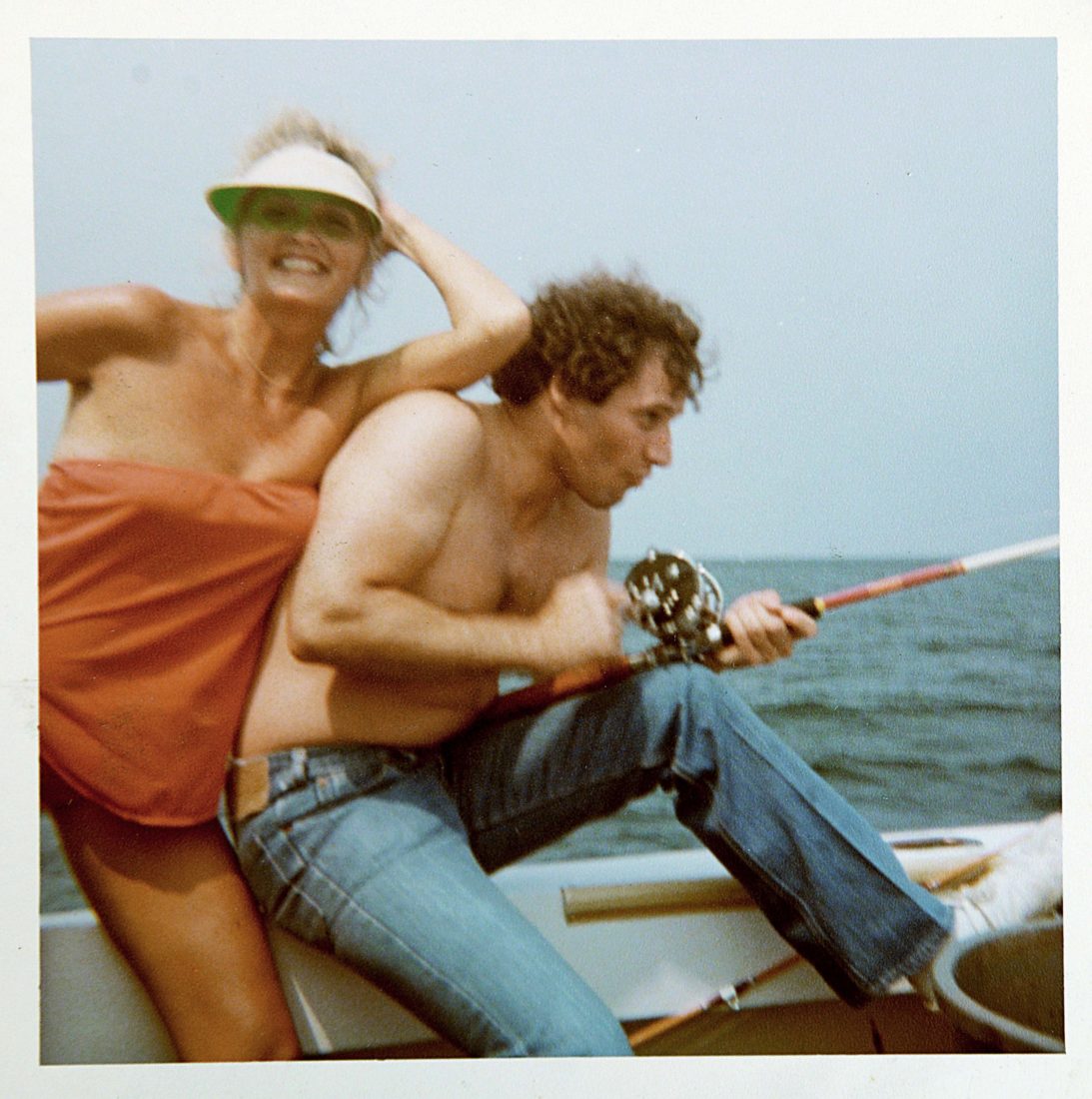

PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE HOWAR FAMILY

Fishing with Bob Woodward in Montauk.

“Your whereabouts is a pluperfect mystery,” the Texas author Larry L. King wrote to Morris, his best friend, in the summer of 1971. After a falling-out with the owners of Harper’s, Morris, then thirty-six, had resigned, packed up his office, and hightailed it out of there. No one could find him. King sent him a letter in care of his sometime girlfriend, Muriel Oxenberg Murphy.

Morris was hiding out at Murphy’s place in the Hamptons. In a letter to William Styron, he wrote that the wind and fog that rolled in made him “slightly loony.” He had wine and a Lab, Ichabod Crane, to keep him company. “When my black dog starts howling, I howl too.” He didn’t want to answer the telephone, so he would hide it in the oven or the refrigerator.

When Morris emerged, he made his way to the local bar hang Bobby Van’s, where he drank with friends Truman Capote and James Jones. He was recently divorced, and it was there he met a thirty-seven-year-old golden girl from North Carolina. Two hot-blooded Southerners had crossed paths, and they began a romance that even their children describe as “torrid.” The two soon became inseparable, splitting time between the Hamptons and Howar’s house in Washington.

Howar’s kids loved Morris. He was a practical joker, told them stories, and typed them long letters. One he signed off, “I enclose $5 apiece for each of you so you can buy some whisky or lollipops or whatever kids buy in the District of Columbia. Your friend, Really Morris,” which was the way eight-year-old Edmond pronounced his name. When Howar got pulled over for speeding on Long Island and Capote was ticketed for drunk driving, they both had to appear in court to resolve matters. Morris printed up bumper stickers—FREE THE BRIDGEHAMPTON TWO—and distributed them to the community.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE HOWAR FAMILY

Interviewing Paul McCartney for Entertainment Tonight in 1985.

At the same time Morris and Howar’s romance was going strong, so was their writing. Sterling Lord had found Howar a new publisher, and she was working on her Washington memoir, Laughing All the Way. And Morris…well, nobody quite knew what he had in the works. After the sale of the home she’d once shared with Ed, Barbara moved her kids into a Georgetown rental they dubbed Cockroach Manor. Morris continued to polish his own manuscript. Both books were set for release in 1973. His novel would be entitled The Last of the Southern Girls.

When twelve hundred people gathered at the Washington Post Book and Author Luncheon in May 1973, everyone was talking about Howar’s book…and whether Morris had also written a book about Howar. Even his publisher, Knopf, played off the mystery, asking in print ads, “Who is The Last of the Southern Girls?” Morris’s son, David Rae Morris, remembered joining his father on the book tour. “Just about every interview made some reference to Barbara and was she the protagonist,” he said. It was becoming a problem.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE HOWAR FAMILY

On set with Liza Minnelli.

Willie Morris at one point told a reporter, “Now you get this down. This is a terrible situation we’re living through… I have worked seriously in the vineyards of American writing all my life. It just so happens that a woman, whom I love deeply, has come out with a book about herself that coincides with my first novel.” When pressed, Howar quipped, “I make absolutely no statement about Willie’s book. It was Margaret Mitchell who wrote the book about me.”

Though Howar was garnering attention, people weren’t reviewing her book, and nobody had bid on the paperback rights. Charlotte Curtis, a New York Times reporter who remembered Howar from a fond encounter at the first Nixon inauguration, persuaded her editors to include Laughing All the Way in the paper’s roundup—and then wrote a glowing review herself. “All of a sudden, it was wow,” Howar recalled. Laughing All the Way climbed the best-seller list, staying there for six months and at one point outselling The Joy of Sex. The paperback rights sold for $150,000, enabling her to move out of Cockroach Manor and into what she called a “spiffy Georgetown house” on Thirty-Fourth Street. Morris’s book sold well, too, but not as well as Howar’s.

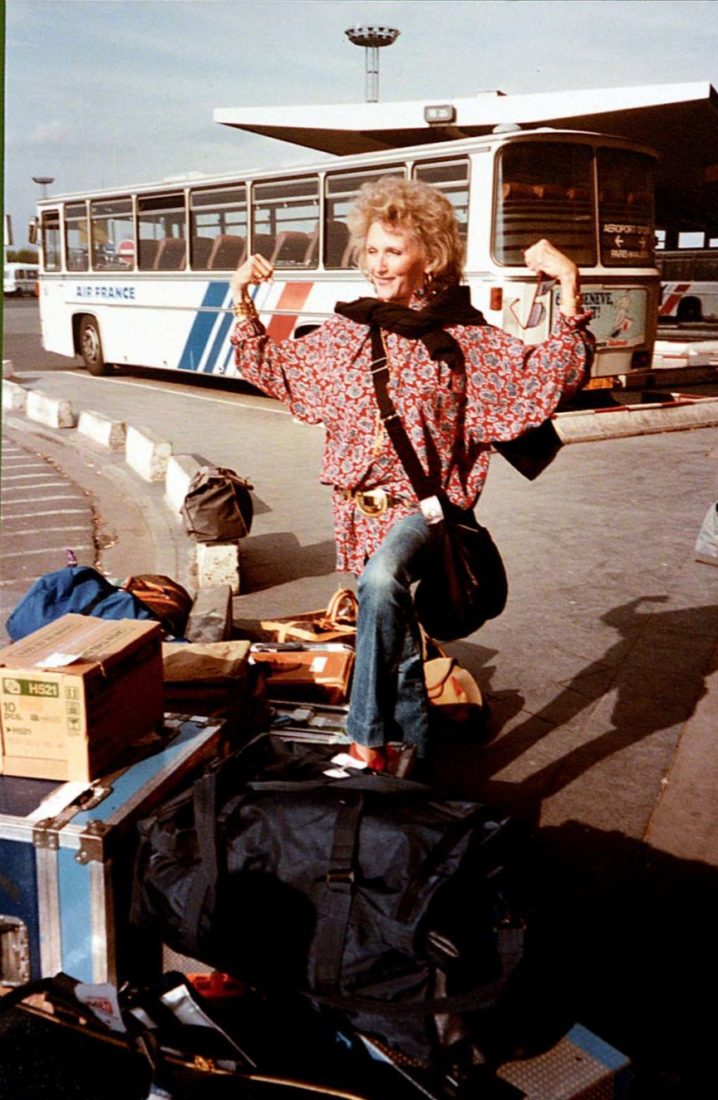

PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE HOWAR FAMILY

Howar in Paris following the Cannes Film Festival in the early 1980s.

We called Ed Yoder, Morris’s fellow Rhodes scholar, to whom he dedicated The Last of the Southern Girls. “I’m not sure why Willie did that,” he said of the dedication, “but my wife calls it Willie Morris’s valentine to Barbara Howar.”

“I get all riled up when you’re on the national tube, develop something like stage fright for you, and am invariably very honored by your performance,” Morris wrote to Howar as she appeared on more shows. “Obviously the courage you show in this and other things fills me with the most curious pleasure and affection. It borders on something very nearly physical, this pride and respect I derive from you when you’re wholly yourself and in command.” Though the words of a man in love, they were no less true: Howar was at her best in her unscripted TV appearances. In particular, she became a favorite guest of Johnny Carson’s for her ability to expose the jugular of Washington politics, without allegiance to a cause or a party line.

The Howar on Carson is smart, witty, and uncompromising. In a 1976 appearance to promote her first novel, Making Ends Meet—which centers around a forty-year-old divorcée—she talks candidly about facing life and a career alone with two children. She’s scalding at times, too, particularly in an October 1977 exchange with the actor Robert Blake, in which she refuses to back down on a cutting remark that suggests he’s a misogynist, even when he offers her a chance to play nice. Howar ends her segment by saying, “I think, Johnny, I might have spoken English a little too clearly tonight for Mr. Blake.”

PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE HOWAR FAMILY

Sharing a laugh with Howard Cosell in the Hamptons.

She saw Morris whenever she stayed in the Hamptons, and he often visited her in Washington, but their romance was tumultuous. “The way it worked is either she threw him out, or he would storm away and go to Bobby Van’s,” recalled David Rae, who was a teenager at the time.

It was not to last. Morris moved back to Mississippi in 1980 to become writer in residence at Ole Miss. Though he and Howar continued to correspond for years, he would stay in Mississippi the rest of his life, eventually marrying book editor JoAnne Prichard. He died of a heart attack in 1999 at the age of sixty-four.

By 1980, Howar was living full-time in New York. She was embroiled in legal battles over two book deals turned sour when the legendary journalist Jim Bellows approached her. He showed her tape of a then fledgling show he was producing. “I look at it and think, who is this saccharine woman giving this saccharine bullshit…and why are you showing me this?” Howar recalled. The show was Entertainment Tonight, and Bellows was trying to persuade her to take the job of New York correspondent. “I was so offended,” she said. But he promised a hard-hitting newscast that would put Hollywood under a microscope. Her friend and powerhouse agent Swifty Lazar encouraged her to accept the offer, telling her, “You’d better take what you can get because you’ve screwed yourself back into poverty here.”

PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE HOWAR FAMILY

On set with Joyce Susskind and Maureen Stapleton for the Joyce and Barbara show.

Howar figured she would sign on for a year; she stayed for five. But Bellows’s original vision lost out to a more corporatized approach, and Entertainment Tonight became a soul-sucking experience. If the Howar of Carson suggested a lion roaming free on the Serengeti Plain, Entertainment Tonight stuck her in the cage of a traveling zoo. The show sent her around the world, to Berlin, Rome, Morocco, Cannes. “I hated every minute of it.”

Her final middle finger to the city ran in the New York Times in 1990—an op-ed titled “You Take Manhattan, I’m Gone.” In it, Howar paints a vivid picture of a city saturated with crime and apathy. “Walking a dog in even a relatively secure neighborhood demands vigilance, lest the animal get bits of broken crack vials in his paws,” she lamented.

And so, after three decades away, Howar, along with her urbane pug, Max, returned to North Carolina. She lived in a rustic homestead in Shotwell, twenty minutes outside of Raleigh. Amid red dirt and copperheads, Howar looked to, as she put it, “re-pot.” She reconnected with old friends whose lives had followed more conventional paths, visited honky-tonks, and once shot up her front porch keeping a snake at bay. She kept a revolver by the bed, as well as a hunting rifle and a shotgun propped among the umbrellas in the entry. Her warning blasts into the night sky at any unwanted visitors earned her a reputation as “the trigger-happy lady.”

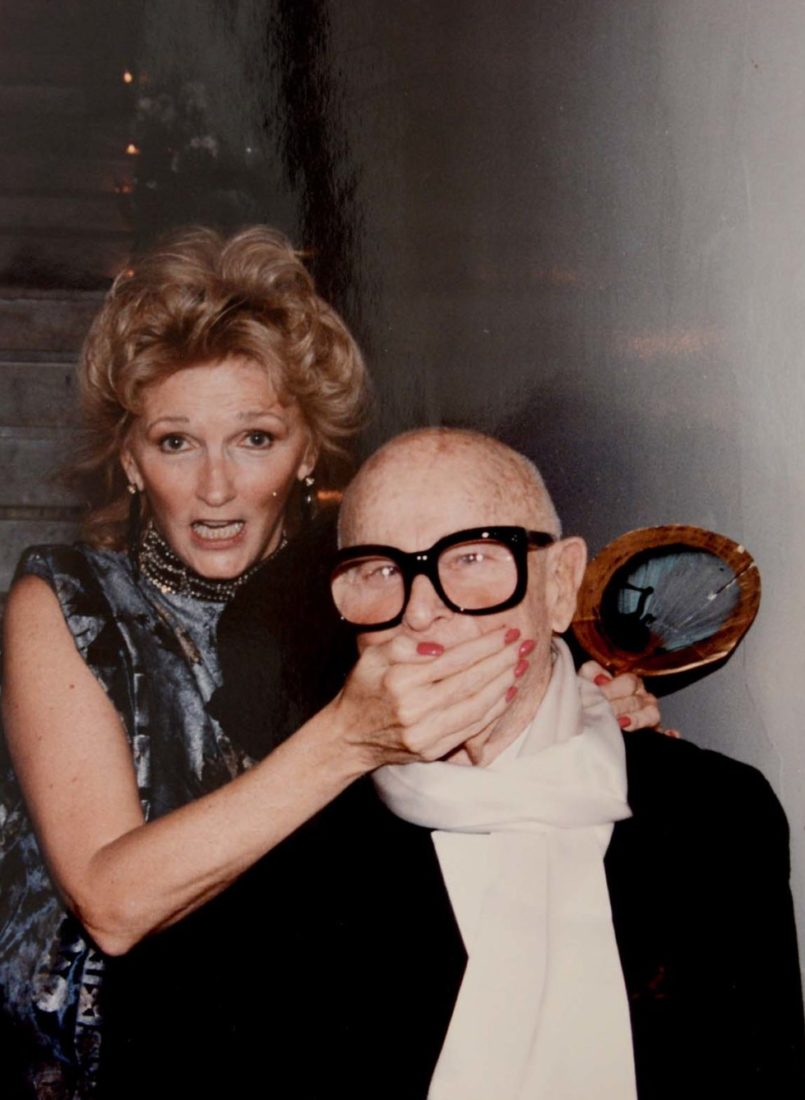

PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE HOWAR FAMILY

With agent Swifty Lazar.

Despite her writing and narrating an Emmy-winning documentary on death-row serial killer Blanche Taylor Moore, Howar’s stint in North Carolina didn’t last long, plagued by her ongoing legal issues with publishers and the stops and starts

of trying to find work. It came to a sad end after two years when she had to file for bankruptcy. She was the hometown girl who’d gone off to the big city and made a name for herself. She was a survivor. But she couldn’t overcome this.

“The sum I was absolved of paying was no release from the shame of pleading poverty,” she wrote in one of her manuscripts, “and as I stood emotionally naked before people who had known my mother and father, and who had followed my personal rise and fall, I promised myself that somehow, someway, I would start my life over and make it count for something meaningful that no one could ever strip from me again.”

In September 1992, Howar moved to Los Angeles to start over and live closer to Bader and Edmond, who were both residing in the city. She began working for Norman Lear, went on assignment for Inside Edition to the first Clinton inauguration, worked on her manuscripts, and spent time with her children and grandchildren.

She kept her special documents packed away—expired passports from her travels, love notes, old photos, letters. And she eventually made good on her promise to share them with us. Her admirers were many. In a letter from Alan Alda, he writes that after reading one of her stories, “I felt I knew you. Your closing paragraph brought tears.”

The collection also includes correspondence from Scottie Fitzgerald, the only child of Zelda and F. Scott Fitzgerald, who was taken with Howar after meeting her in Washington in the mid-sixties. In 1986, she sent Howar a package containing twenty years’ worth of clips of the “marvelous publicity” she had collected from Howar’s life. “It was one of those glamorous moments in time which can never be repeated,” Fitzgerald wrote.

And then there are the letters from Willie Morris. “I constantly learn from you, and you fill me with wonder,” he wrote to her on November 30, 1973. “You are splendid, in every way of that word…” He signs off, “Hell, Barbara, I’ve written you a love letter.”

When we finally spoke to Howar in 2018 about writing a story on her life, she demurred at first, saying she didn’t think anyone would be interested. But it seemed to us she deserved something more than what the internet remembered of her. “Swinger.” “Hostess.” “Socialite.” In a 2006 piece in Memphis magazine about “Boy Wonder” Willie Morris, she’s traduced as “Georgetown hostess Barbara Howar, whose claim to (unlasting) fame was party-giving, a bestseller no one remembers, and a TV talk show with Maury Povich.” One can imagine her colorful response to such a dismissal.

The last couple of years have been difficult ones for Howar and her children. She moved to a board and care facility in the San Fernando Valley in 2019, and dementia is now robbing her of her memories. The pandemic has prevented visits from her family, her living connection to her past. And worst of all, as she might say, she’s had to give up her signature tequila and cigarettes.

We asked Edmond who the love of his mother’s life was. “Willie,” he said. “That was four years of a relationship—a long time for her. And it was a time of great success for her…Everyone loved Willie. But,” he acknowledged with a laugh, “some people didn’t love Barbara.”

At Ole Miss, where Morris’s papers are housed, 173 boxes hold a literary life—manuscripts, revisions, contracts, correspondence. The letters from Howar to Morris are observant, witty, and revealing, like Howar herself. In one from 1980, she writes: “My adored Willie, I think it was always in the cards for you and me to have just the wonderful, explosive and unique years we had; the good Lord never really lets two people like us pair off together for long. No, He makes us spread ourselves around and leaves us with haunting memories…without which the both of us [would] wither and blow away.”

We wanted to solve the mystery of who inspired one of the great Southern writers. We found Barbara Howar. She’s been called many things throughout the years, but “pioneer” belongs in the lexicon, too. She broke ground and scorched earth in equal measure. As Edmond said, she was opinionated before that was considered “appropriate” for a woman. And though she may have paid a price for it, she always was who she was, on screen and off.

Whenever Edmond told his friends about one of her adventures, they would remark, “Wow, your mother did that?” Edmond would say to them, “She did more than that.”

No comments:

Post a Comment