‘That experience of floating into the film. It’s giving up those things that hold you to the Earth into the story of the film. It is a wonderful sensation.’

– John Boorman

Being an extract from notes towards a documentary on the life and films of John Boorman, the celebrated director and writer of ‘Point Blank’, ‘Hell in the Pacific’, ‘Leo the Last’, ‘Deliverance’, ‘Zardoz’, ‘Excalibur’, ‘The Emerald Forest’, ‘Hope and Glory’, ‘The General’, ‘The Tailor of Panama’ and ‘Queen and Country’, amongst many others.

Part One: In which we speak to our hero over the phone.

John Boorman says he’s old.

The director, writer, diarist, filmmaker is eighty-eight.

I don’t think of him as old. Never thought of him as old. Still don’t think of him that way. Strange how we never think of our heroes as old but just as they were when we first encountered them.

John Boorman lives alone. He lives in Ireland residing in the house he bought from the money he made from Point Blank.

A few years ago he fell in the kitchen and broke his thigh. He wondered if he would be able to drag himself up and phone for help. Then he wondered if he should? Thankfully, he did.

(Age never arrives empty-handed.)

I spoke to him over the phone. Line clear, his voice strong, with a joy those a quarter of his age would envy.

Opening scene: A river. A boy, John Boorman, swims against a current. The river twists, froths, pulls the boy. He is drowning. Boorman sinks to the bottom of the river.

A crowd of people on the river bank shout to the lock keeper to close the sluice gates on the weir.

The lock keeper shakes his head, the boy might get trapped in the gates and drown.

Boorman opens his eyes and looks up. Air bubbles to the surface. A plane flies overheard. A Messerschmidt? The air bubbles cloud the surface. The plane briefly looks like the floating godhead from Zardoz. The water blurs. Boorman slips through the sluice gates. He is drowning, held down by the force of water.

The lock keeper casually walks across. Looks into the tumult. Closes the sluice gates. He blindly probes the water for the boy. He hooks Boorman to the surface. On land, the boy coughs, splutters, gulps air. He is reborn.

John Boorman: Nearly all of my films have a river in them. I always feel comfortable when I’ve got a river. I love the way that water, moving water reacts to the film. It doesn’t quite happen in the same way with digital. There is something about the film emulsion the way it’s exposed to water that some magic occurs.

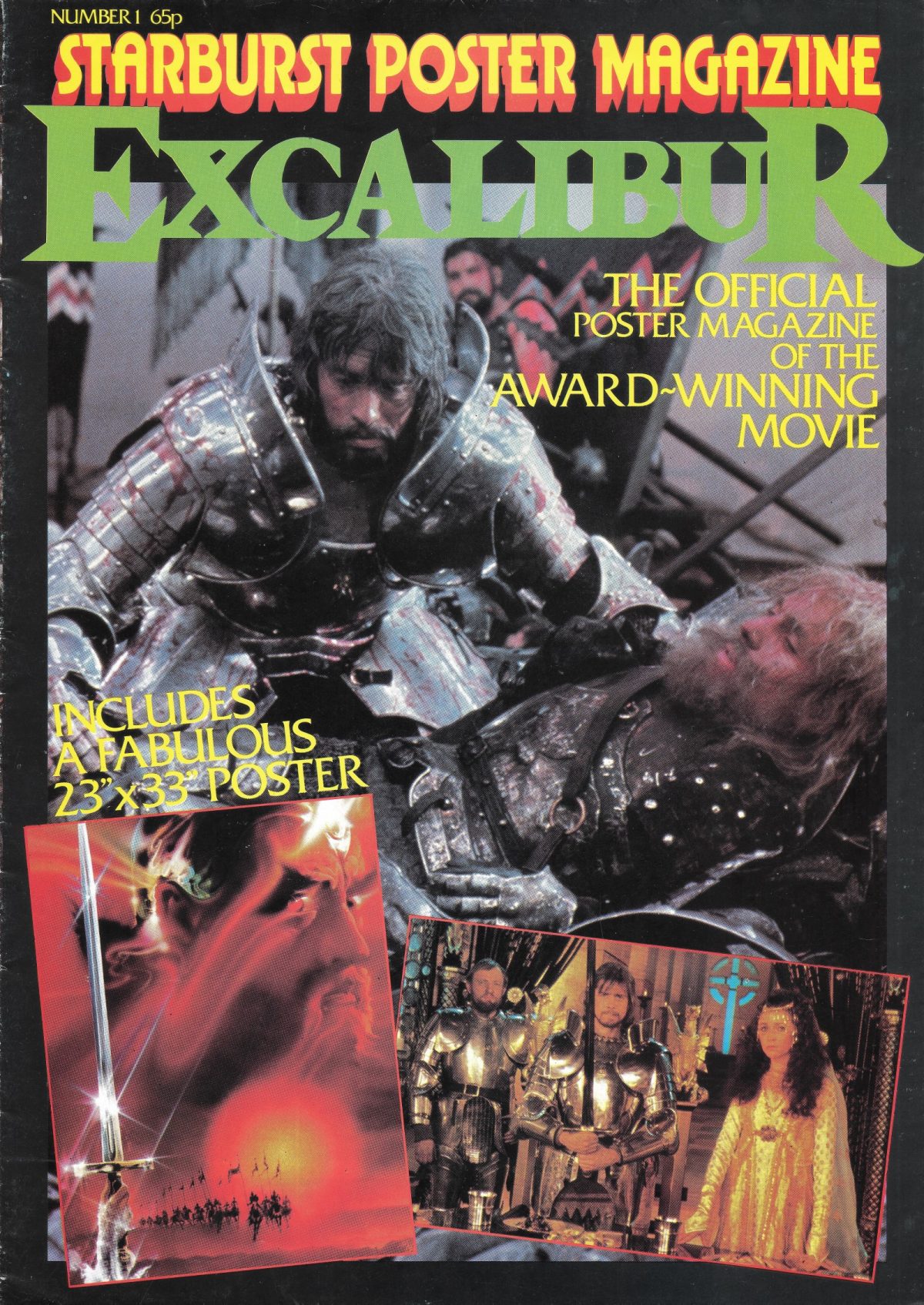

Rex Images: John Boorman – 1981

What makes for a successful film?

Boorman: There is one characteristic that all successful films have in common which is luck. Because there are so many things that can go wrong with a film. Whether it is something as simple as bad weather or bad casting that doesn’t quite work or something that doesn’t go. It’s a precarious thing altogether to make it work simultaneously with a crew and a cast. It’s a wonderful feeling when it’s all happening and everybody is pulling all their own weight, it’s great. But often it’s not quite right and you’re trying to pull it yourself.

What happens to the most successful and most unsuccessful is when you start shooting, the first few days you feel you’ve got the weight of the film on your shoulders. You are dragging everybody along. I mean they don’t get it yet. They don’t really understand. They’ve read the script but don’t really understand what the film is about and how it comes to life. Then after the first week or so, they start to get it, they start to understand it. Once everyone is pulling in the same direction–it’s a wonderful feeling. You’re no longer having to drag the whole picture along with you on your shoulders it becomes a thing shared.

When everything is working together the film almost makes itself.

How did you become a director?

Boorman: I became a director organically really because I started out editing and I learnt editing from a very good editor. Then I started to go out and direct little documentaries and bring them back and edit them and they got steadily longer, more and more substantial. Then when I was working at the BBC, I gradually used actors and dialogue mixed with the documentaries.

Huw Wheldon was in charge at the BBC. He was a brilliant leader. He had his favourites and I was one of them along with Ken Russell, John Schlesinger, and a few others. We were asked to do daring things, which we did [laughs]. Huw was a very interesting man and I made a number of films for him at the BBC which was really a learning process for me.

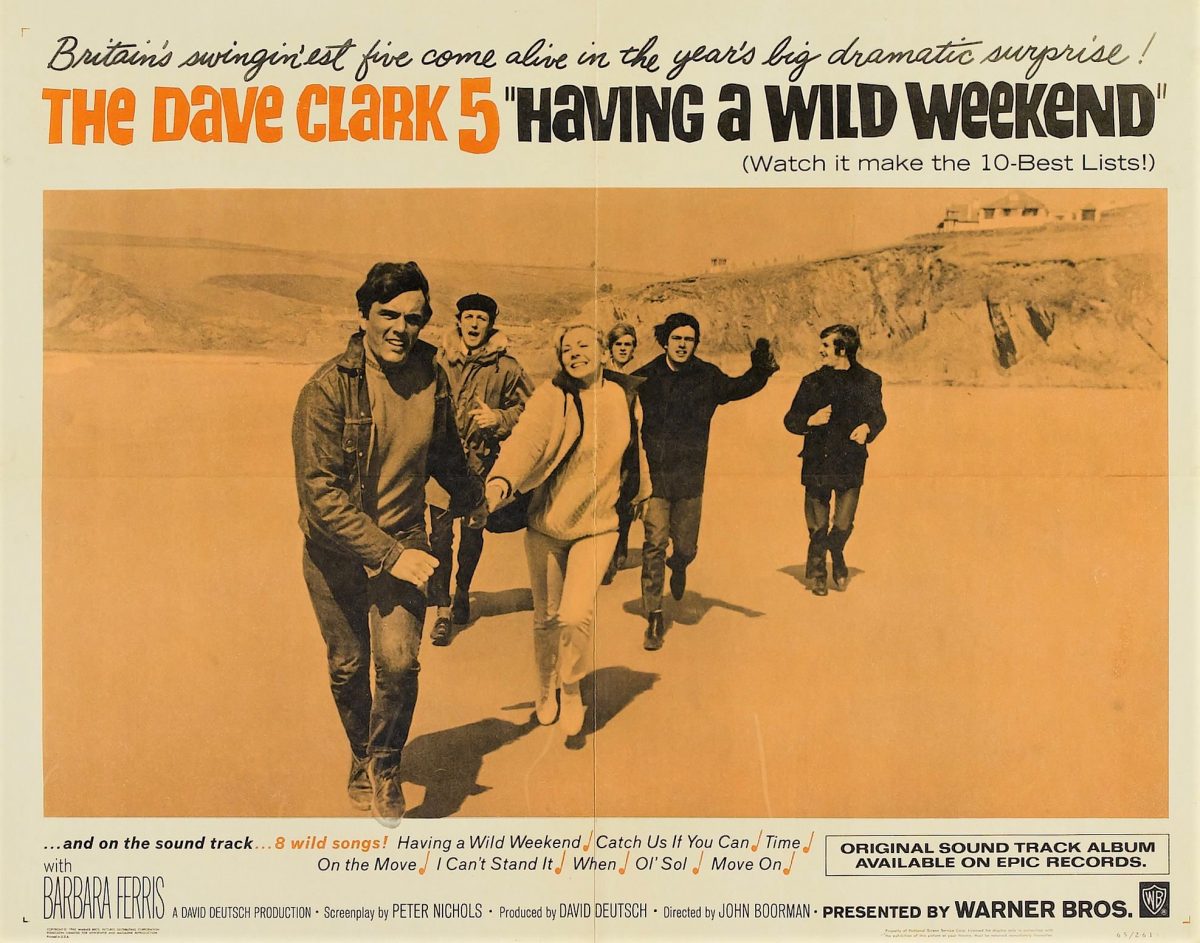

The experience of working at the BBC gave Boorman an offer to direct his first feature film Catch Us If You Can starring the Dave Clark Five.

Boorman: When I made the Dave Clark Five film, I continued this notion of introducing several of my documentary elements. It was very much a mixture of documentary and feature.

Catch Us If You Can had a good script by playwright Peter Nichols. Rather than copying the madcap antics of The Beatles in A Hard Day’s Night, the Dave Clark Five were cast as five different characters escaping the constraints of their lives. The film proved a critical success but did little box office business. However, it gathered enough notice to bring Boorman to the attention of Hollywood.

Boorman: When I went to Hollywood to make Point Blank I knew how to make a film because I had Lee Marvin on my side. He understood much more than I did how difficult it was going to be to make the kind of picture I wanted to make. He did everything to help me. He called a meeting with the Head of the Studio and the producers and he reminded them that he had cast approval and he had script approval. He was very hot at that point, he had just won an Academy Award for Cat Ballou. Marvin said, ‘I defer my approvals to John.’ Turned on his heel and walked out. I had the Head of the Studio and the producers glaring at me. They had lost the film in one meeting. I had final cut on my first film in Hollywood.

It was because of that I was allowed to colour scheme the whole picture. Every scene had a single colour. The Head of the Art department wrote a memo to the Head of the Studio and said, ‘This film will never be released. There’s a scene with seven men wearing green shirts and green ties.’ Of course, the interesting thing about that is no critic every noticed it. Because the way you perceive colour on film is quite different from how see colour with your eye.

I have been very influenced by a book called Optics by Isaac Newton. I read it when I was at school. I read like a novel because it was so exciting. The things he was discovering about optics and the way they behaved and how they relate to the eye and how different colours take a different amount of time to decay from the retina. You have to be very careful in mixing colour. You get a loss of tension by seeing to many colours floating about.

Lee Marvin in Boorman’s ‘Point Blank’. Note the colour of the decor is replicated in Marvin’s tie.

Point Blank was based on Richard Stark’s novel The Hunter. Surprisingly, Boorman never read the book before making his film. He worked from the script. The first screenplay was written by David and Rafe Newhouse. Boorman thought it dated and a “slighly nostalic gangster story in the style of Raymond Chandler–another Harper if you like.” What appealed to Boorman was the central character and the situations which he thought were very relevant to modern America. As Boorman told Michel Ciment:

What I wanted to say in the film (and, no doubt, it’s a cliche) is that American society is killing itself; and it’s on a course for self-destruction.

Boorman discussed the script with Lee Marvin while the actor was in London making The Dirty Dozen. Both men hated the script but liked the central character Walker. With Boorman granted complete control over the film, he brought in Alexander Jacobs to help rework the screenplay.

The film touched on many of the ideas that recur throughout Boorman’s films:

The use of colour–in the background of Walker’s (Lee Marvin) long walk through the airport terminal, the colours on the wall are replicated in the decor, dress, and design of each scene as the film progresses..

The central character is on a quest for a Grail, or meaning, or in this case money–this relates to Boorman’s enduring love for the Arthurian legend. In Point Blank there is also an allusion to the betrayal of King Arthur by Guinevere and Lancelot.

Boorman: One of the things that concerns me deeply is the way in which experience gradually allows you to understand yourself or the characters you are portraying. You are putting them in settings where they are tested, you try to explore them and try to find out who they are and what they’re potential is. That’s always in my mind.

The Grail legend has been a great influence on me all my life–since I was a child really–because it’s a quest–the quest for the Grail, the notion of lost innocence and the notion of trying to recover it. Recover the wholeness. That’s what the Grail is about.

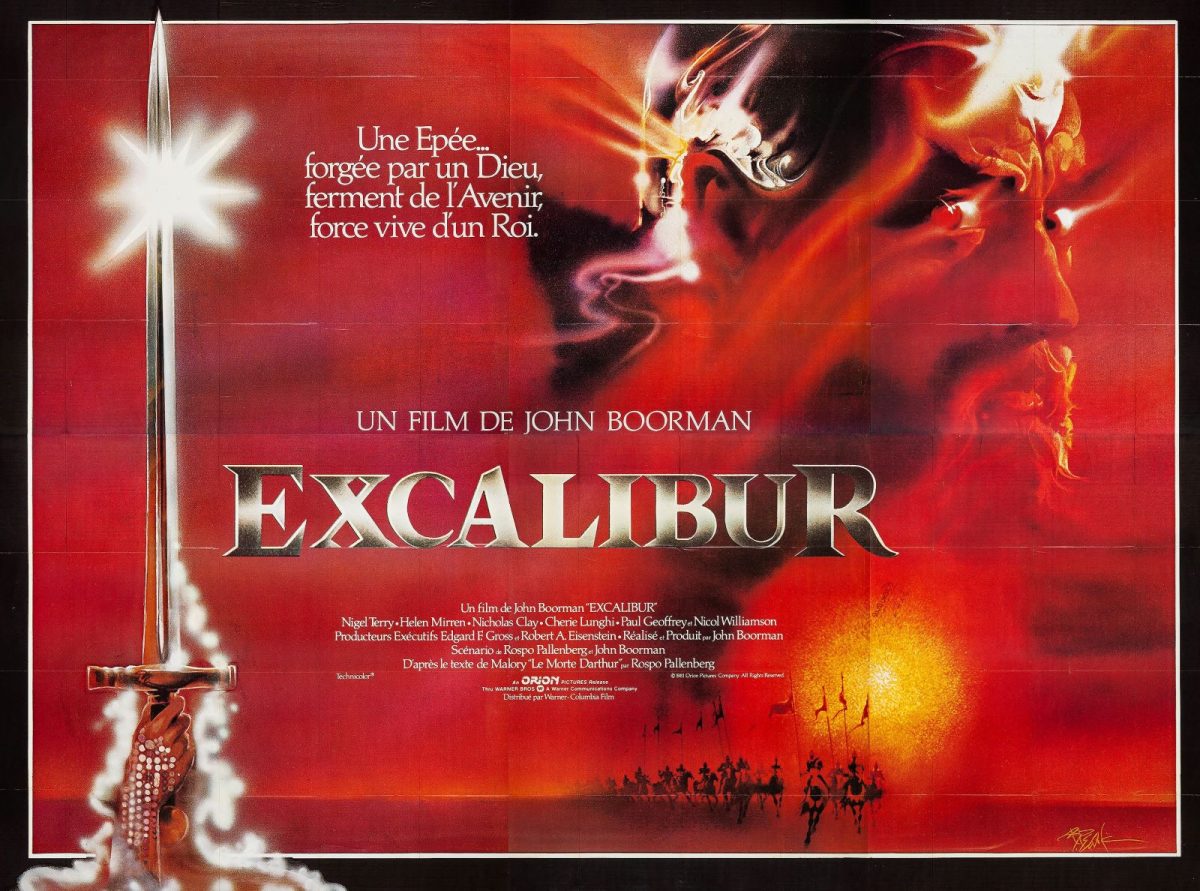

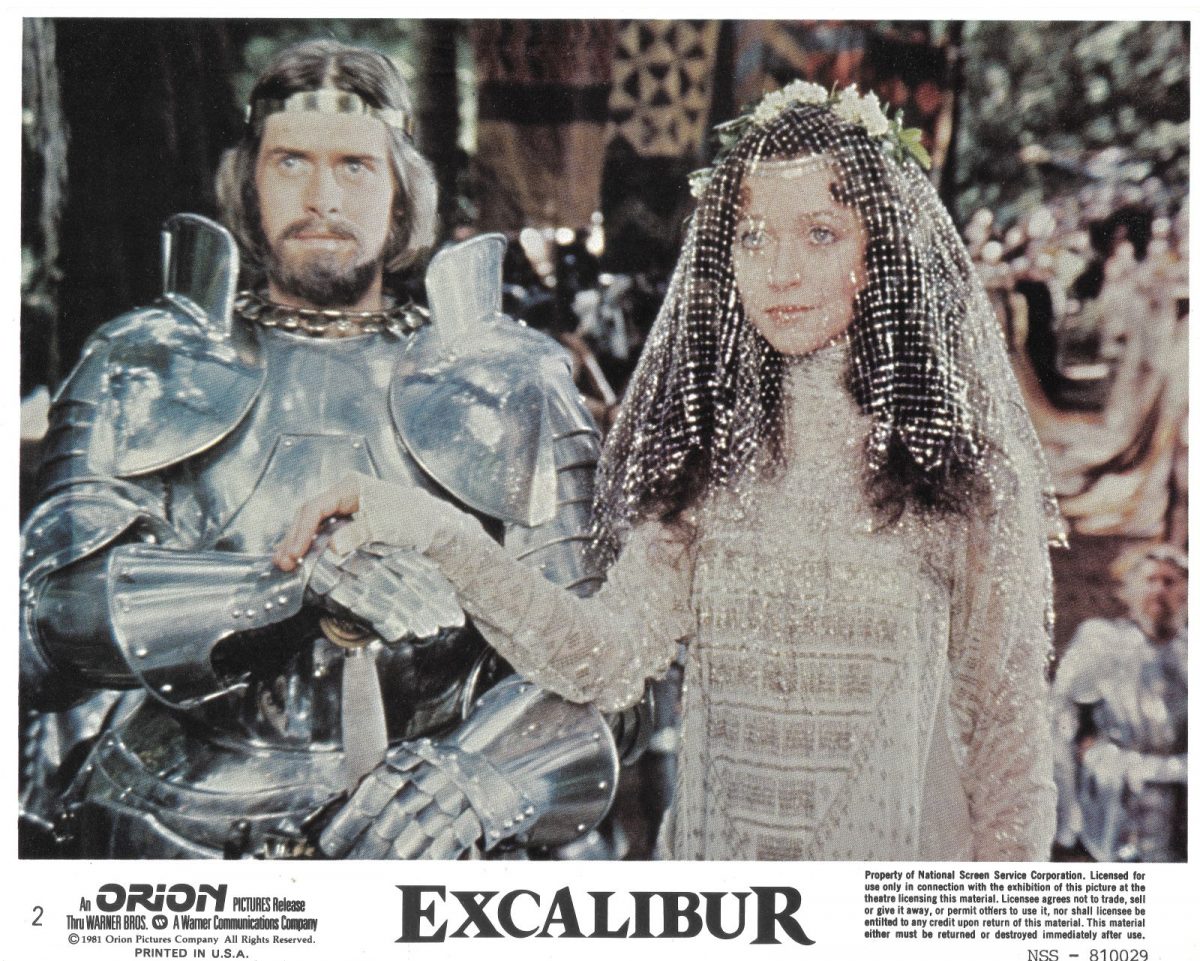

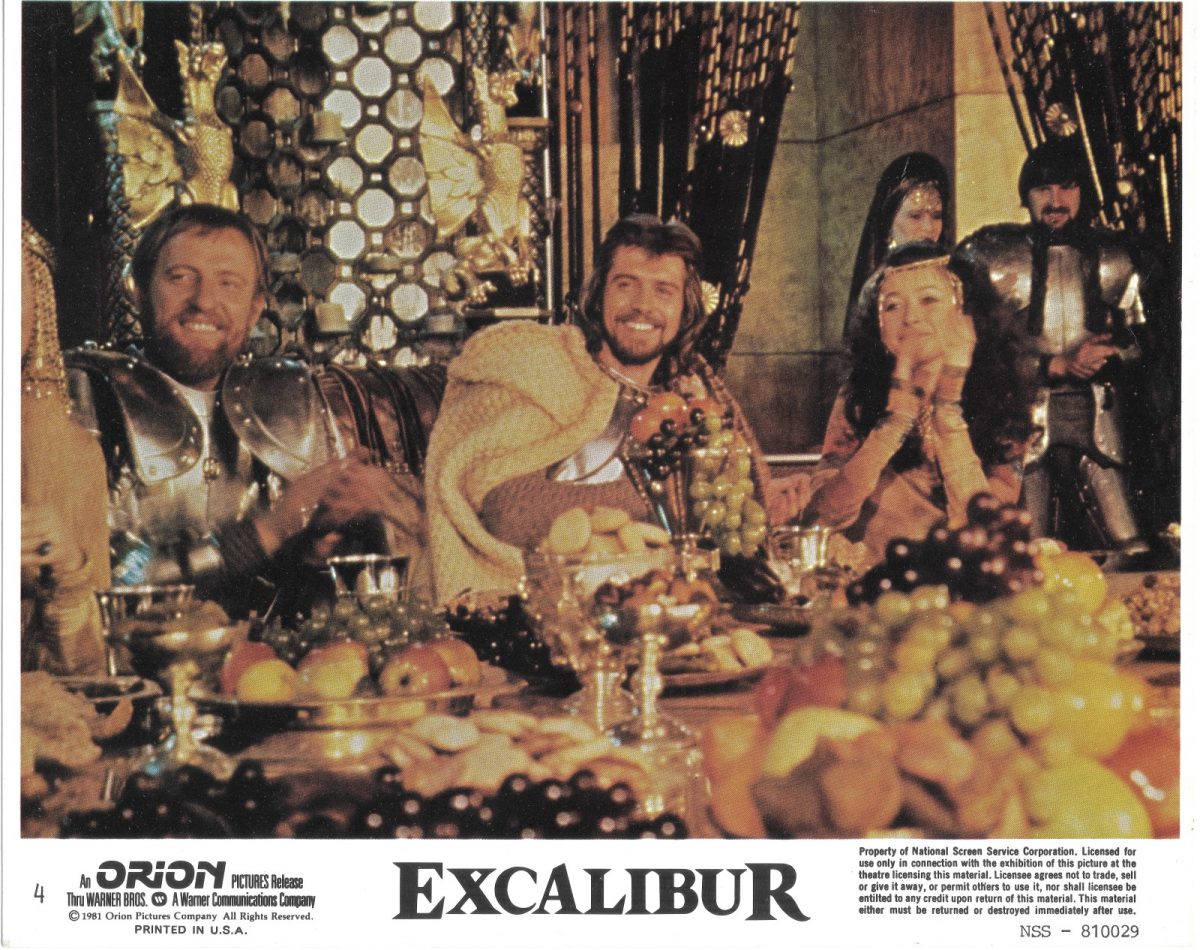

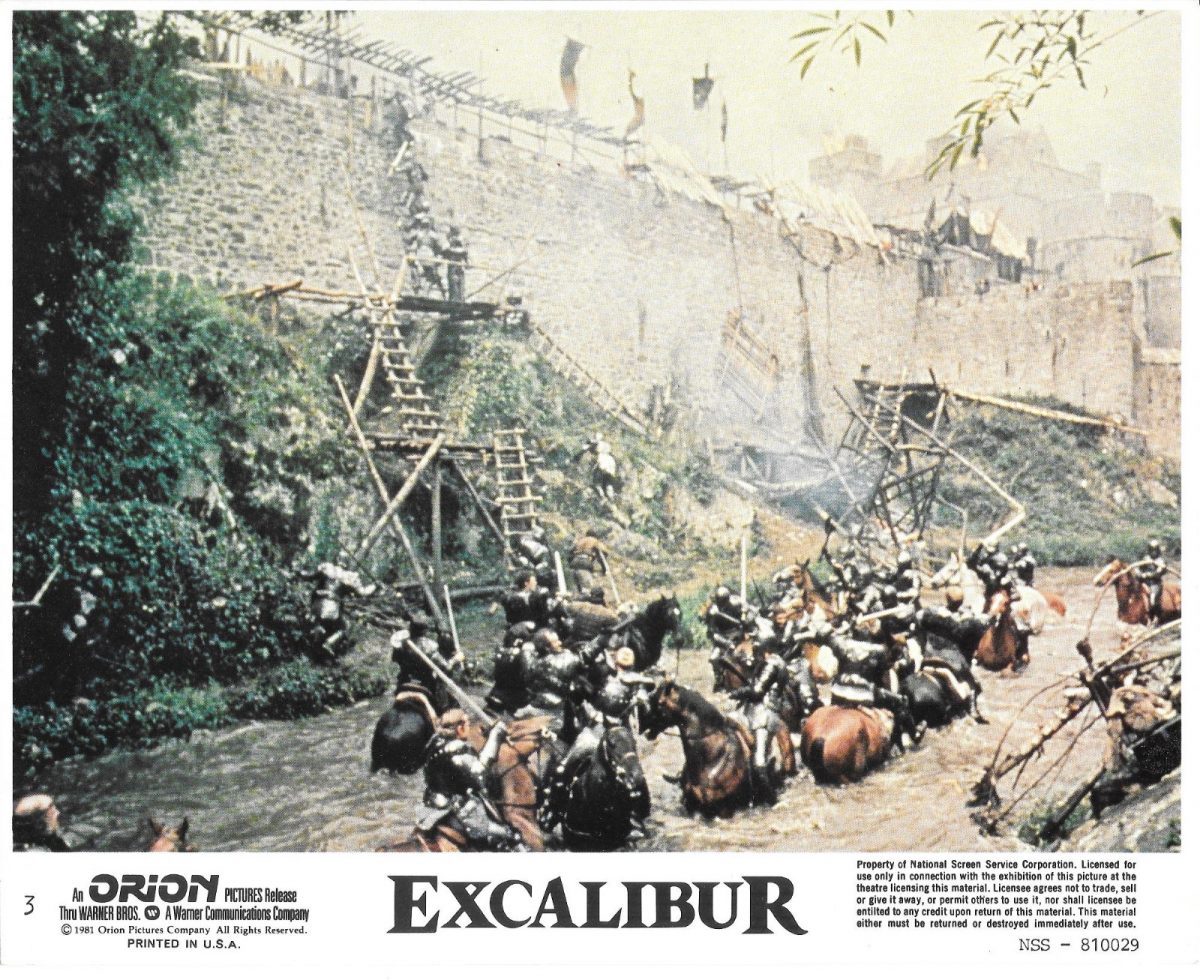

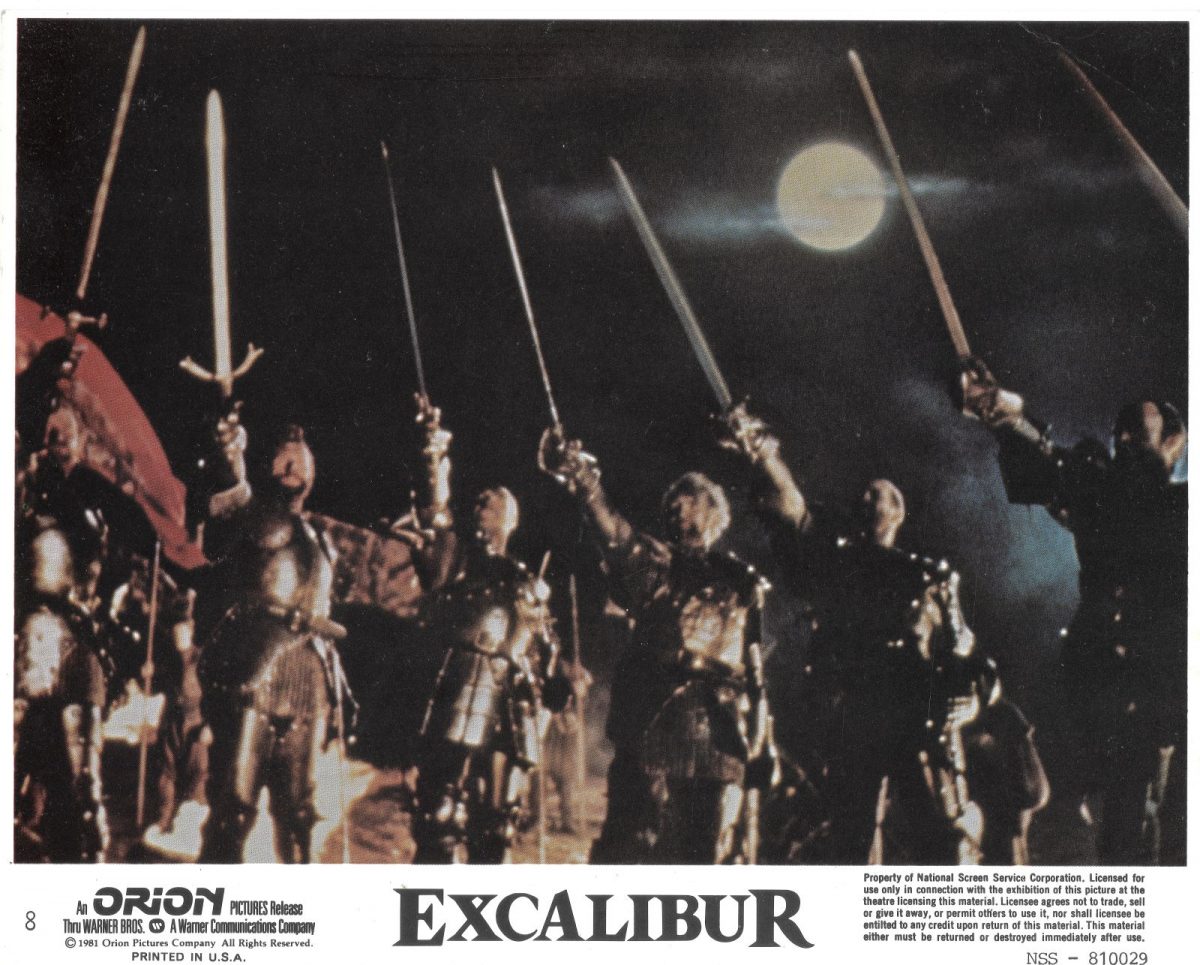

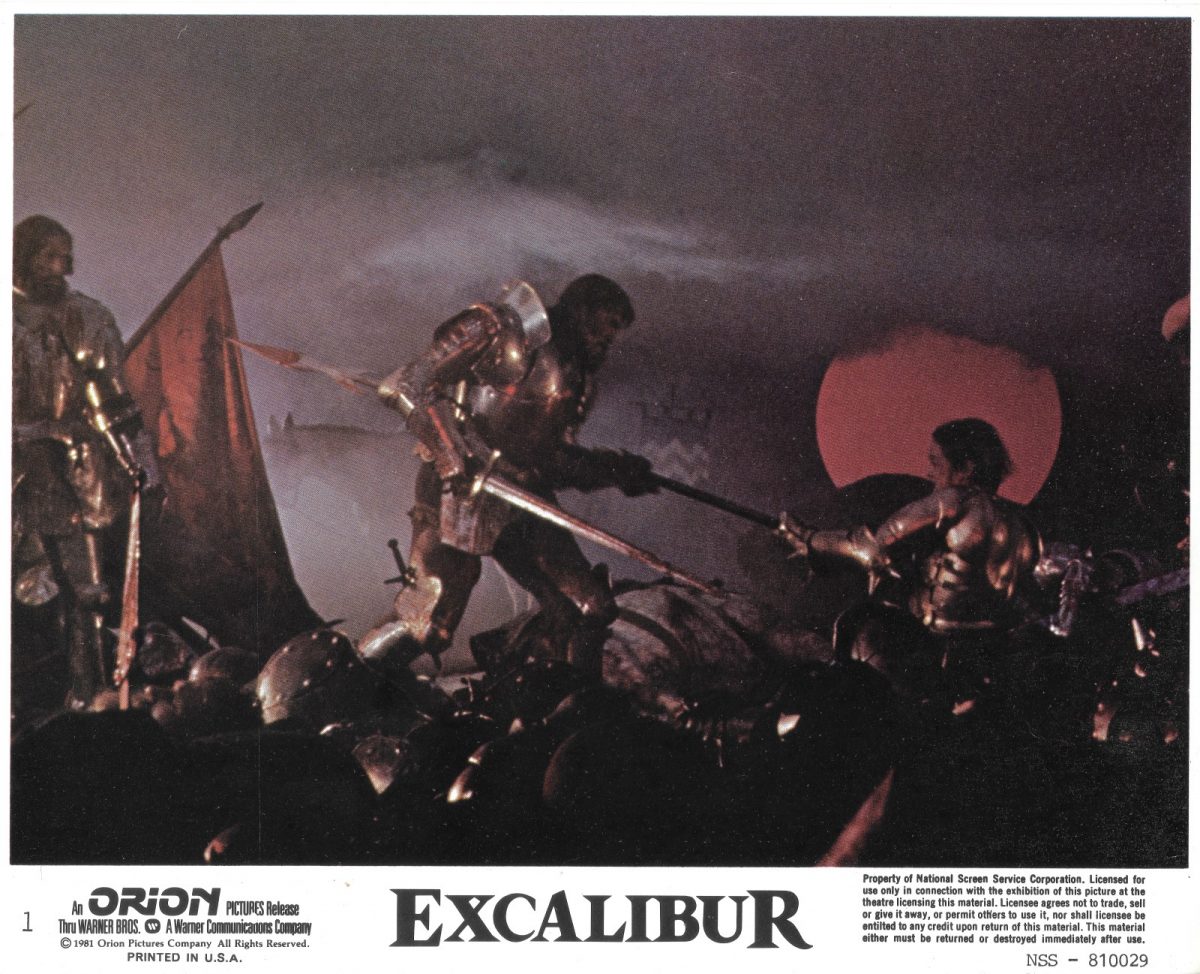

Excalibur, Boorman’s eighth film, may be described as a culmination. By directly addressing himself to the cycle of Arthurian legends, he brings to a close twenty years of reflection on the interrelated themes of the Grail and the quest with which all of his work has been embued.

– Michel Ciment

Boorman first wrote his screenplay on King Arthur just after he completed his third movie Leo the Last. The Arthurian myths and legends of the Knights of the Round Table had “really marked” Boorman’s childhood. In particular, T. H. White’s The Once and Future King. As Boorman explained to Michel Ciment:

Then at school, it was Idylls of the King, the Victorian version which Tennyson wrote as a favour to the Queen. But I had never read the original texts. It was later I came to them, and I was extraordinarily impressed by them: Malory’s Morte d’Arthur, the works of Chrétien de Troyes and, especially, the most fascinating and modern of them all, Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parsifal. There are the three great books, Englidh, French, and German, in which our national cultures are inscribed. Malory leads directly to T. H. White, Chrétien de Troyes to Bresson and Rohmer, von Eschenbach to Wagner.

Boorman worked on his script. But the Studios lost interest and thought it would better if he worked on a screenplay of J. R. R. Tolkein’s The Lord of the Rings. This was how Boorman met his friend and creative collaborator, Rollo Pallenberg. The pair worked for six months on their script. Then the film was abandoned as Studios once again lost interest. Boorman was deeply upset but it proved “a tremendous kind of exercise” for Excalibur.

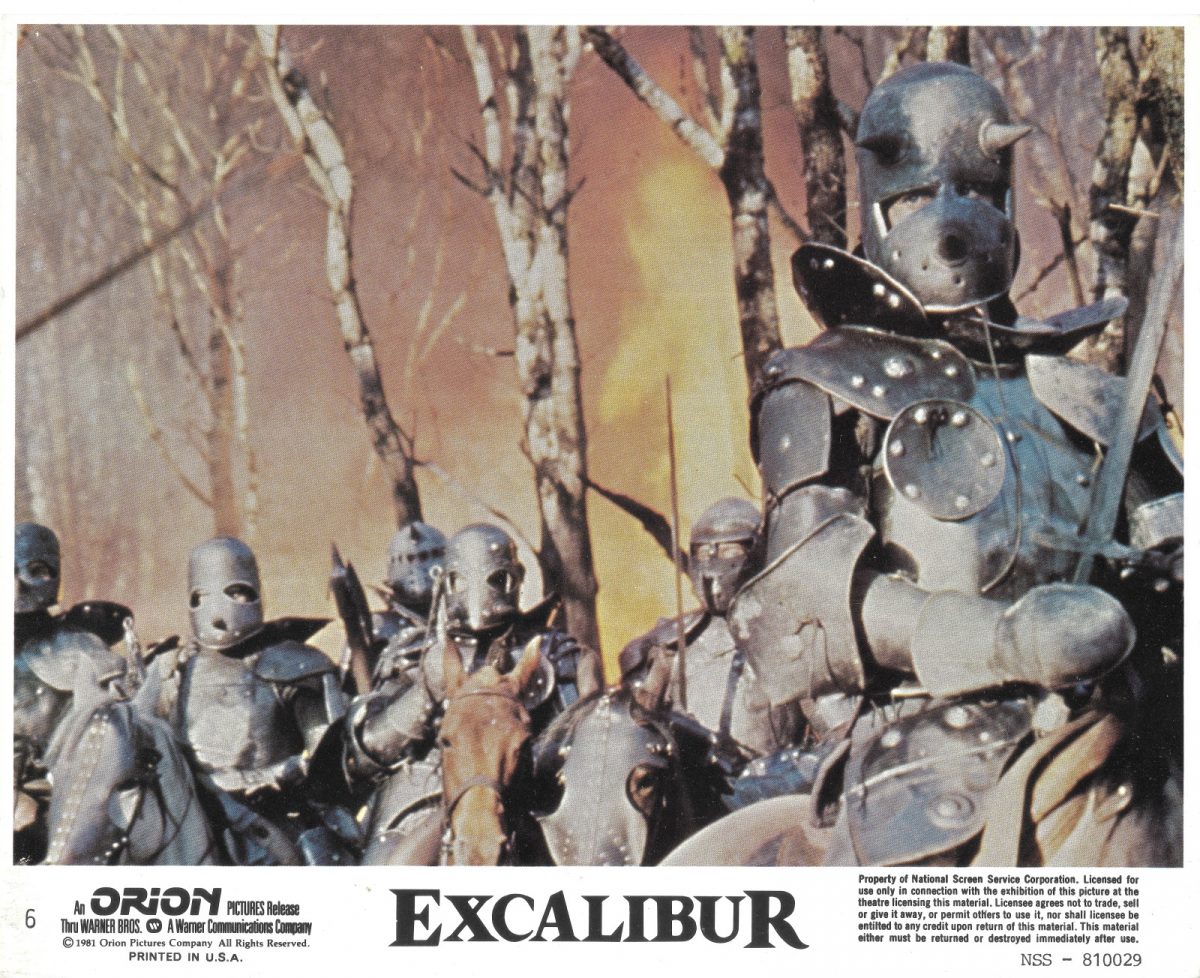

Boorman: I wanted to cast Excalibur with young actors. Most of them at that time like Liam Neeson and Gabriel Byrne were completely unknown. I’d seen Liam Neeson on the stage he was wonderful. I got three or four young actors in, I had them improvise and so forth, in fact Pierce Brosnan was one of those young actors who came in and he improvised and we worked out scenes. He acted really badly and he realised it too. He left the studio where I was rehearsing and he went out and it was raining and he had an old car and he couldn’t start it. He walked back to his basement flat. He said he decided he was no good at acting and he was going to give it up. He told me this much later on. He almost gave up acting after auditioning with me. He then got a small part in that film The Long Good Friday where he sits in the back of a car with a gun and he became a star overnight. I love Pierce, he is great, I think he’s terrific in The Tailor of Panama.

Casting is so important. You know the old story about the actor who keeps going up on his lines and he has to do take after take. He can’t get it and he says to the director, ‘I’m very sorry,’ The director says to him, ‘It’s not your fault, it’s mine, it’s my fault–I cast you.’

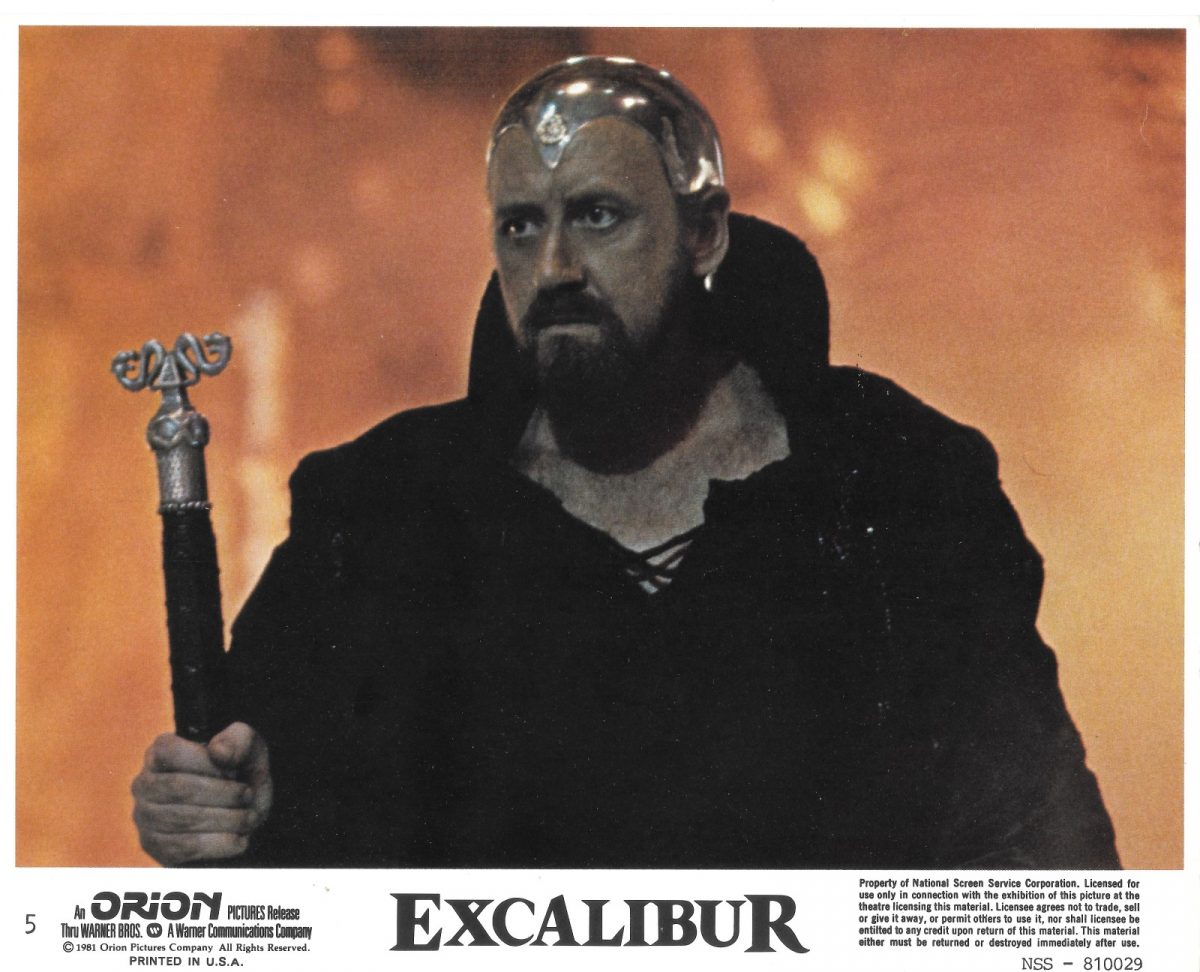

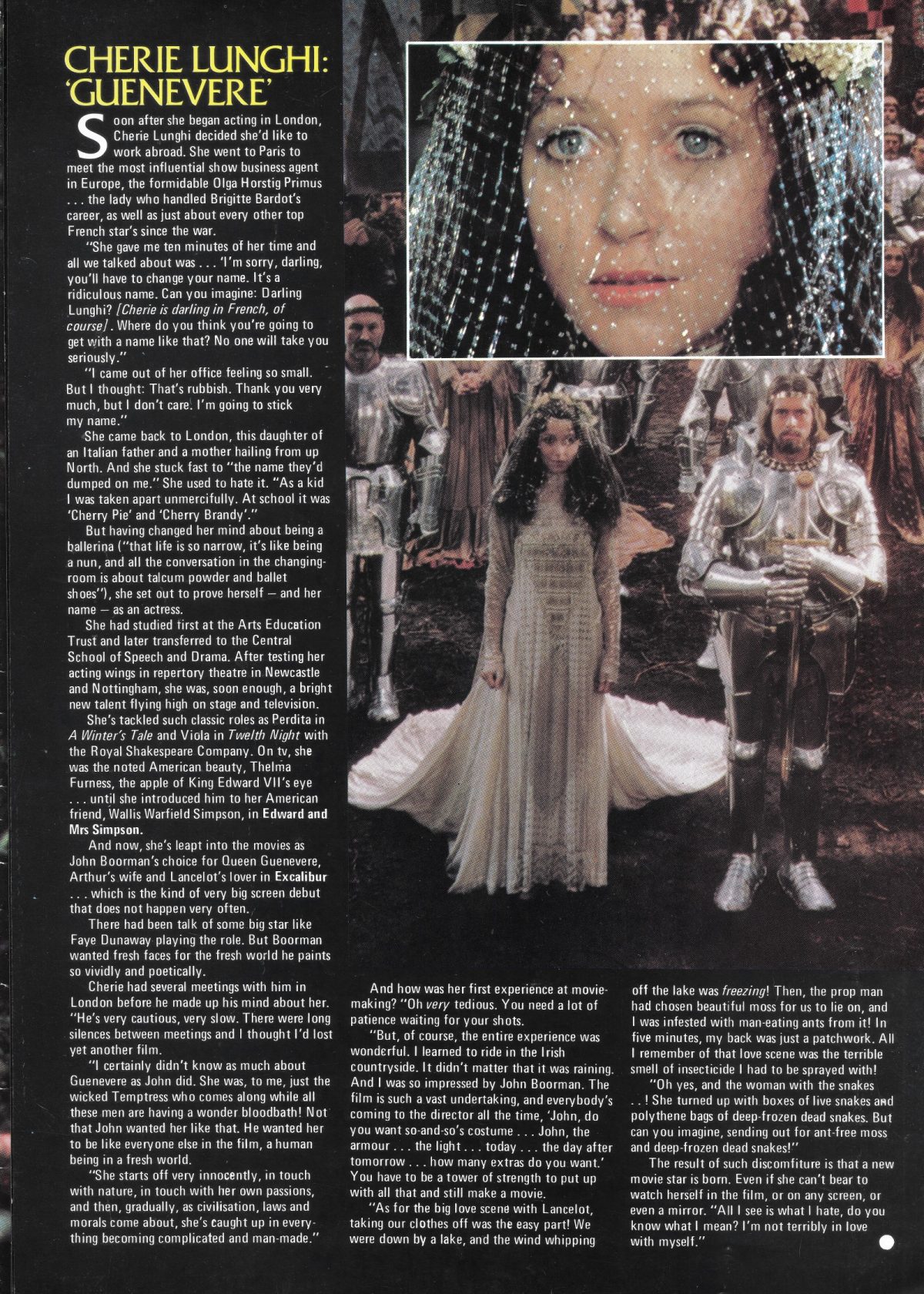

For the role of King Arthur, Boorman chose Nigel Terry, who went to have a very successful career, most notably making a series of films with Derek Jarman. For Guinevere he cast Cherie Lunghi. For Morgana he chose Helen Mirren. The role which Boorman dreaded casting most was Merlin.

Merlin’s involvement in Excalibur is like the role of a director to making a film. In the same way a director can see how a film should be and what will be the end product, Merlin possess the gift “of seeing into the future and understanding the past.” This makes him “a representation of the unconscious. For the unconscious contains a kind of magic and even, if you like, the notion of the dragon that one finds in Merlin’s story. The dragon is the prehistoric creature, the reptile, in all of us, the id rising out of the depths of the swamp, with all the terror that supposes.”

Merlin understands what should happen and where it will lead. Original suggestions for the role included Sean Connery, Lee Marvin, and Max von Sydow. But Boorman opted for the Scottish actor Nicol Williamson.

Depending on when and where he was asked, Boorman will say Williamson understood the role completely, or alternatively, has claimed Williamson had difficulty finding himself in the role until he tried on Merlin’s copper skull cap. Then he fully inhabited the role

“There’s something very disturbing about [Williamson], too, which was perfect for me. I wanted to make Merlin unpredictable. He’s frivolous when you expect him to be serious and he’s solemn and melancholy in the sense of a lost past and weariness of life.

“It’s wonderful to see a role coinciding with an actor’s temperament like this.”

Boorman’s daughter Katrine, who appeared in the film as Arthur’s mother Igrayne, thought Williamson played the role more like her father because “Merlin is Dad.”

John Boorman directing Nigel Terry, as Arthur, on how to remove the Sword from the stone.

Casting was important, but so was the look of the film. Boorman wanted to create a vivid dreamlike world.

Boorman: We made the decision with Excalibur that any exteriors were to be lit with strong green filters so all the greens became luminous. Because we were talking about a world of imagination really. We wanted to give it that slightly other worldly feel. It was like our landscape but it was suddenly different like the imagination at work.

Movies are always better for us when you subject an audience or rather when you present an audience with these combinations of images and sound they act like metaphors and I think the audience understand them without knowing why or how. I think it the films, well, the good films anyway can talk directly to the audience’s subconscious.

That experience of floating into the film. It’s giving up those things that hold you to the Earth into the story of the film. It is a wonderful sensation.

I think that’s when you get that feeling when you’re watching a film a director has made everything you are watching is relevant and meaningful in different ways–emotionally or intellectually. That’s a wonderful feeling when that happens.

No comments:

Post a Comment