Once upon a time, this man brought the vote to the most frightened and most oppressed black citizens of the Deep South. He braved the jeers of a mob for the sake of integrating southern education; he marched in solidarity across Selma's Edmund Pettus Bridge. As head of the United Negro College Fund and the National Urban League he raised millions of dollars to help blacks gain college educations and job training and decent housing.

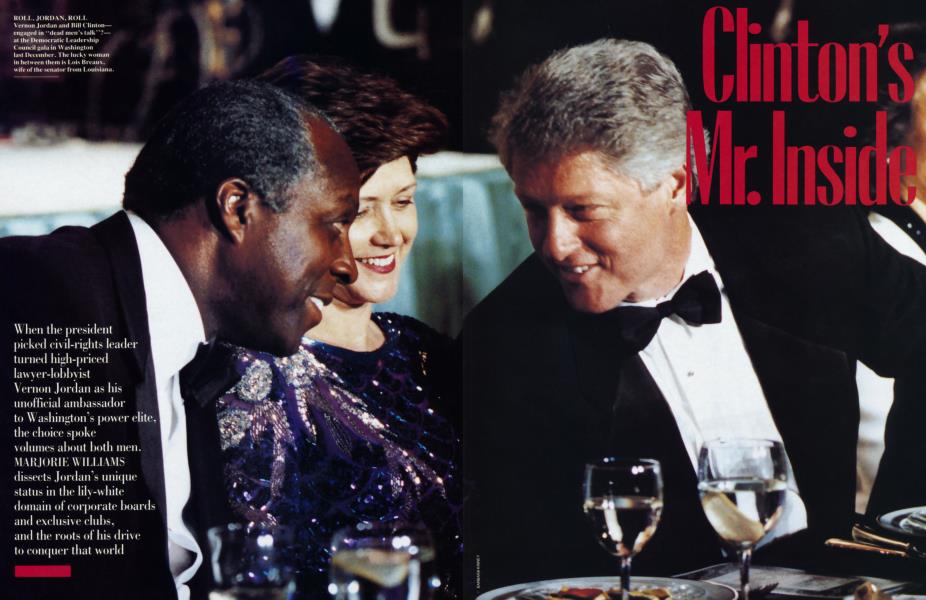

Now he cocks a perfect wingtip against a drawer of his desk, pressing his long frame back into the smoky-blue leather of his chair. His suit is an immaculate charcoal; his shirt, London's best, is a subtle stripe of white and yellow and gray. The yellow fabric of his necktie, spotted with more gray, is echoed in the handkerchief that winks from his breast pocket. He wears chunky gold cuff links, a gold watch thin as a stick of gum.

"It's not extremes," he is saying of the great, great distance he has traveled. "It's breadth." He is describing, in part, the journey of the self-made man, a drama doubly moving when told by one who has overcome all the hurdles assigned in this country to those born with black skin. The grandson of a sharecropper, the son of a caterer and a mail clerk, Vernon Eulion Jordan Jr. is, at 57, a close confidant of the president of the United States. He is richly educated and widely known, a wealthy man and a happy one.

But Jordan is also acknowledging his transformation from $35-a-week civil-rights lawyer and N.A.A.C.P. field director to seven-figure corporate hired gun, a journey whose moral resonance is much less clear. Today, he is everything that America loves to hate about Washington: a lawyer-lobbyist, a rainmaker, an influence peddler. He sits on 11 corporate boards—including the board of a tobacco company that once tried to market a cigarette explicitly targeted at blacks. He is a managing partner in one of the most politically aggressive law and lobbying firms in Washington, Akin, Gump, Strauss, Hauer & Feld. He makes between $1 million and $2 million a year.

When Bill Clinton appointed him to chair the presidential transition in partnership with Warren Christopher, another well-heeled corporate lawyer, it sparked doubts about how seriously the new president intended to follow up his campaign rhetoric on taming Washington's special interests. On a more personal level, it threw into a sudden spotlight the quiet contradictions that rule Vernon Jordan's life.

Naturally, Jordan quarrels with the premise that his former life and his current life are hard to reconcile. "It's a continuum," he says. "If you have some notion that sitting on X, Y, or Z board makes me forget how I got there... or the people I met along the way, then you have totally miscalculated me."

But consider his left lapel, where he sports the crimson ribbon that signifies empathy with sufferers of AIDS. In Vernon Jordan's version, the ribbon takes the form of a tiny pin, less than an inch high. Against the rich austerity of his clothes, it is but a small, pleasing dash of vivid color: the perfect totem for a man who values his liberal politics, but rarely lets them clash with his overall design.

Among the various good-government Democrats who have waited 12 long years for the election of a soul mate, Jordan's appointment to head the transition was greeted with mild shock. But when reporters groped to explain precisely why, they were plagued by the standard journalistic necessity to find the smoking gun, the single fishy deal or seamy alliance that constitutes an official conflict of interest. The one they came up with most often was Jordan's service on the board of RJR Nabisco, Inc., the nation's second-largest tobacco company. Didn't his $50,000 annual fee from RJR create a conflict for a man who might help choose the next secretary of health and human services, the next surgeon general?

It probably did. But the real discomfort created by the appointment wasn't susceptible to that kind of analysis. It sprang from nothing illegal, nothing that could be called unethical by the technical definitions that rule the city. It wasn't any one specific business connection that made Jordan's appointment surprising; it was his very identity in Washington.

Vernon Jordan's friends and connections constitute a gallery of power, money, and fame, ranging from Democratic grande dame Pamela Harriman to Federal Reserve Board Chairman Alan Greenspan, from financier Theodore Forstmann to NBC anchorman Tom Brokaw, from former housing-and-urban-development secretary Jack Kemp to former secretary of state Cyrus Vance. His board work makes him a colleague of Henry Kissinger, Nancy Reagan, and more than two dozen current and former C.E.O.'s of major U.S. companies. He relates on a first-name basis to former president George Bush, who invited him to White House parties, lunched with him privately, and sometimes sought his advice. (Indeed, he found himself last year in the curious position of advising both President Bush and candidate Clinton on how they should respond to the Los Angeles riots.)

Charm is Vernon Jordan's essence. Above all there is the smile, a sweetly gorgeous thing he flashes like the asset it is, like a wad of cash.

Every summer he rents a house on Martha's Vineyard, not in the traditionally black section of Oak Bluffs, but in the predominantly white community of Chilmark. "Kay Graham," he notes offhandedly, "runs the best kitchen on the Vineyard."

He lives well. Since the mid-70s, he has ordered his shirts from London, custom-made by Turnbull & Asser or Charvet to his 17½-37 measurements. He and his wife, Ann, live in a generous brick house, purchased in 1986 for $550,000, that sits on a hill overlooking Georgetown. They both drive Cadillacs—his a red Allanté convertible. He has a passion for fine cigars, and requires that a single flower in a bud vase grace his desk every day.

He is a trustee of the Brookings Institution and the Ford Foundation, and he belongs to all the right clubs: in New York, the Century Association, the University Club, and the Council on Foreign Relations; in Washington, the Metropolitan Club, the Alfalfa Club, the Kenwood Golf & Country Club, and the Robert Trent Jones Golf Club in nearby Gainesville, Virginia. He is a member of both the Trilateral Commission and the Bilderberg Meetings, the high-status European policy confab. When Bill Clinton got his first invitation to the meetings in 1991, it was as a guest of Vernon Jordan.

His corporate success makes him a source of complex feelings among African-Americans. There are those who "see Vernon as someone who takes care of himself—who only looks out for Vernon," in the words of one black Washingtonian long involved in civil rights. But for others it is a source of great pride to see an African-American so successfully join the white elite in its own game.

Within that elite, the moral dignity of Vernon Jordan's first journey, up from poverty and past the obstacles of race, has tended to obscure who he really is and what he's really after. His long history of service to the civil-rights movement is a form of camouflage.

The week after Jordan's appointment, for instance, the New York Times editorial page tied itself in knots trying to find the correct tone with which to treat Jordan. First it soundly damned his tobacco connection, in a tough unsigned editorial written by black staff member Brent Staples and titled "Vernon Jordan's Ethics." The next day—apparently without any pressure from Jordan or anyone else outside the paper—it issued a convulsive clarification, couched, on the orders of publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr., as an entirely new editorial, titled "Vernon Jordan's Integrity." Jack Rosenthal, who then ran the editorial page, explains that he "just felt a little sheepish" about how harsh a headline had accompanied Staples's editorial, and that he and Sulzberger "both agreed that it needed some redress." The second editorial, he points out, said very much the same thing as the first. But, in fact, its tone was so much more tentative, more ingratiating, that it amounted to a striking act of insecurity from the newspaper of record.

"I'm convinced," says one well-known liberal on the Times staff, "that if we'd written that about the standard Washington white guy, we would never have backed off it."

Similarly, Jordan has always benefited from the fiction that he is a breed apart from the real lobbyists who crowd Washington law firms, including his own. Amid the controversy following Jordan's appointment, The Wall Street Journal (whose parent company, Dow Jones, numbers him among its board members) reassured its readers that, while Jordan's law firm "does engage in high-powered lobbying and represents foreign interests," Jordan himself "is primarily a corporate lawyer."

But of course he's a lobbyist—though at a level so exalted that he is able to present himself as transcending the petty pleadings of his brethren. And now, after just 11 weeks' work in Clinton's transition, he is poised to become the lobbyist in chief, his profile hugely increased by the universal knowledge that he is a Clinton-administration insider.

After my first interview with Jordan—a short, somewhat wary meeting on a Friday afternoon in December—I am expecting to hear from his secretary, or from a Clinton-transition spokesman, about scheduling a second interview. But when the call comes, it is his own beautiful voice that flows from the phone: deep, southern, musical. "Marjorie," it wheedles without preamble, as to an old friend. "You're not done with me yet?"

Charm is a difficult thing to describe, but charm is Vernon Jordan's essence. Says his old friend Eleanor Holmes Norton, the District of Columbia's delegate to Congress, "It's a combination of a personality that seduces men and women differently, but nevertheless seduces."

There is the touch—the lingering handshake that greets you, and the hand that on parting squeezes your shoulder, salutes the small of your back. There is the instant mastery and constant use of your first name. There is the steady gaze—full on, never wavering from your face. Above all there is the smile, a sweetly gorgeous thing he flashes like the asset it is, like a wad of cash.

Finally, there is the way he tells a story. In 1988, Jordan says, he offered some minor advice now and then to the Dukakis campaign. Michael Dukakis "was going to speak to the National Baptist Convention," Jordan recalls. "And they sent me this talk and said, 'Please read it and get back to us.' And so I get it and I read it and I call them back and they say, 'What do you think?'

"And I say, 'You all ever heard of Jesus ?'

"They say, 'What do you mean?'

"I say, 'You all ever heard of Mo-ses? Sojourner Truth? Harriet Tubman? Booker T. Washington? W. E. B. Du Bois?'

"They say, 'Yeah, what are you talking about?' "

Jordan's voice is now wreathed in sarcasm. "I said, 'This speech quotes John Winthrop fi-i-ive times. John Winthrop doesn't mean anything to 40,000 black Baptists.' "

Jordan himself is a famously compelling speaker. He once reportedly instructed D.C. mayor Sharon Pratt Kelly, a woman of somewhat icy mien, that she had to emote more in her speeches. "Giving a speech is like sex," he told her. "You're supposed to be exhausted when you're done."

There is something marvelous about watching Jordan deploy his charms, the swagger with which he uses his difference from every white lawyer in Washington.

"He's not a charming carbon of a white man," notes Norton. "That charm is unmistakably black. Nobody who listens to Vernon can doubt that it all comes from the blackest of roots." She has put her finger on something important: Jordan is not someone who succeeds by "passing." In talking about him, blacks often observe that he is remarkable for having succeeded in spite of the fact that he is very dark-skinned. Says Julian Bond, who was a founder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and later became a Georgia state legislator, "There used to be a joke in Atlanta, in the early 1960s, that the way you could prove a restaurant was integrated was that they would serve Vernon Jordan. ... Because he's so tall, he's so dark. He's so him."

It's safe to say that none of the other high-powered lawyer-lobbyists in Washington quote Scripture the way Jordan does, as many as four times in the course of a single breakfast. (He even wields the Bible when I press him on why a man with his history as a black leader would lend his symbolic weight to the board of a tobacco company, given the grim imbalances in the rates at which African-Americans smoke and die of smoking-related diseases. "I made that decision in 1980, when I was asked, and I'm not ready to back away from it," he says. "There's an old, old biblical inscription which says, 'Woe be unto him who puts his hand upon the plough and turns back.' ")

Another part of his currency is gossip: he is a joyous purveyor of news and speculation about his huge circle of acquaintance. "Dead men's talk," he will say invitingly, leaning across the lunch table to dish. "This is dead men's talk, now."

With men, his style is a towel-snapping, slightly ribald wit. He's a great teller of dirty jokes, according to one old friend, who says, "He never does not have a new story to tell."

With women, he is universally flirtatious and has long had a reputation as a ladies' man. Howard Moore Jr., a former colleague from Jordan's earliest civil-rights days, recalls that "when he was still in the South, women would break out in a sweat talking about Vernon in his tennis shorts."

Watching him greet the women who cross his path during his workday—his fond attention to every waitress on the breakfast shift; a chance encounter with Tipper Gore in the hall outside his transition office ("Now, you must do Vernon justice," she purrs. "He's just the best"); the passing affection he lavishes on women colleagues at Akin, Gump while waiting for the elevator—one imagines him fine-tuning a sophisticated weapon, turning up the dial until it is set on "Stun."

"He flirts outrageously," notes one of a chorus of women friends. "Holding hands, long looks in the eyes. ... It goes a little over the edge, maybe, sometimes, but nothing that makes you feel harassed. Vernon's not slimy."

Another woman, however, remembers having him to a large, formal dinner in the mid-80s, before he married his second wife. Midway through their dinner badinage ("He was pretty hard to talk to, because it was all innuendo"), Jordan suddenly observed, "You look like a woman who likes to fuck."

"I was speechless," says the woman, who could think of no riposte until later in the meal, when Jordan had turned his attentions to a friend who was seated nearby. Dinner? he was pressing her. Tennis?

Hearing the second woman tentatively agree to a tennis date, the hostess leaned across the table and warned, "If you play tennis with him, you better wear your diaphragm at net."

To understand how Jordan has reached the top, it helps to think of his life as the tale of two cities, yesterday's Atlanta and today's Washington. For his youth in the first of these segregated cities prepared him especially well for his eminence in the second.

Jordan was born in 1935, the middle of three sons. He was named for his father, a mail clerk at a local military base. But the key to Vernon Jordan, clearly, is the force of nature who gave birth to him, a small but powerful woman named Mary Griggs Jordan.

The daughter of a sharecropper from Talbot County, Georgia, she started a catering business in the Depression and labored seven days a week to boost her family into the middle class. Although the Jordans were poor, "Vernon was less poor than most of us," recalls Lyndon Wade, president of the Atlanta Urban League.

Mary had a posh clientele on the city's north side, in the highest reaches of Atlanta society, for weddings, teas, cocktail parties, dinners. In the office from which her youngest son, Windsor, continues to run the business, two photo albums show the daily backdrop of the Jordans' lives, page after page of white: the white of fine linen, of deviled eggs and thickly iced wedding cakes, of brides' dresses, of Mary Jordan's uniform, of her clients' faces.

From their earliest days, Vernon and Windsor Jordan were in and out of those clients' houses. They passed hors d'oeuvres, washed up, poured the punch; in summer, they stood sentry by the buffet and shooed flies away with giant fans made from newspaper. From pre-adolescence, Vernon learned to serve as a bartender, pouring for revelers after Georgia Tech–Vanderbilt football games, mixing drinks at Georgia Tech fraternity parties—places he would never, under any other conditions, have been invited to go.

Everyone who knows Vernon Jordan thinks those experiences were formative. Says Lyndon Wade, "It takes some of the mystery out of how the other side lives. It tells you there is another side.... And I think it helped give him an idea what money and power were all about."

The main lesson absorbed from his mother, according to Windsor Jordan, was this: "It was like you knew there were two worlds, two life-styles. And the idea was to get to that other style."

That style was also displayed at home, where Mary Jordan made her family the same fancy food she made for her clients. "We wanted to eat chitlins and collard greens and things," says Windsor, laughing. Most excruciating for the little boys, he says, were the sandwiches they found in their lunchboxes: elegant things, the crusts cut off, chicken salad or papery slices of ham. "You couldn't match it up against a good Spam sandwich."

It wasn't as though Jordan had only white models to consult. Atlanta, in the 1940s and 1950s, was a relative mecca for southern blacks. Thus, though the city was rigidly segregated, even a poor black boy had the opportunity to see people like him in the roles of doctor, university president, banker, lawyer—men like A. T. Walden, who litigated the earliest civil-rights cases. And Vernon lived near Atlanta University Center, the enclave that houses six historically black colleges, including two of America's best, Morehouse and Spelman.

Atlanta's thriving black middle class is often cited as a reason the city produced so many leaders of the civil-rights movement. But "what set Jordan apart," says Julian Bond, "was that he also saw into the other world."

Jordan made it clear he was breaking with his past. "He said, 'I ain't no civil-rights leader anymore,'" recalls Eleanor Holmes Norton.

Every month, from the time Vernon was 13, Mary catered the meeting of the Lawyers Club of Atlanta—filet mignon and strawberry shortcake. Vernon was especially fascinated by these men. This was something different from admiring the handful of black lawyers he knew; it was only when the white bar gathered that he could see lawyers as the rightful rulers of their own subculture. It was the number of them, the ease of them, that struck him.

"I liked the way they dressed," Jordan recalls. "I didn't like the way they talked, necessarily; I didn't like what they said, sometimes not stuff that I thought was right. But I liked their demeanor, their decorum. I was impressed by that, and liked the way they wore their shirts and stuff." Even at a young age, Jordan was attuned to matters like clothes. "Vernon was always conscious of being dressed," remembers Windsor. "Going to school, I'd always have to stop and wait for him to go back and change again, so he'd look, as we'd say, sharp."

Though Brown v. Board of Education was decided the year after Vernon graduated from high school, the civil-rights movement was not a chief concern of Mary Jordan's. "With my mother, it wasn't about color," stresses Windsor Jordan. "It was about money. It was about business and money. She'd say, 'If you got some money, you can do most anything you want.' "

When Vernon was ready to graduate from high school, an honor student, he took all these lessons to heart. With the encouragement of a New York service organization, he looked north to choose a college, and enrolled in Indiana's DePauw University (Dan Quayle's alma mater), where he would be the only black student in his class. "I liked it because it was different, and I liked it because it was a challenge," he says.

When it came time to pick a law school, however, he chose D.C.'s black Howard University. By then it was clear that the most important legal work in the South was in the area of civil rights, and Howard was the chief training ground for those who were bringing legal challenges to segregation in state after state.

By 1960, Vernon was ready to go home, armed with a law degree and an ambition large enough to encompass both a revolutionary social movement and a desire to make good.

While Jordan's friends tend to romanticize his civil-rights years as two decades of self-sacrifice, detractors tend to describe him as a man of more flash than substance—a civil-rights leader whose eye was always on the corporate path. The truth is less simple than either of these formulations allows. For Jordan, as for many other participants, civil rights was legitimately a career as well as a cause. And just as his work today bears traces of his civil-rights work, his years in the civil-rights movement foreshadowed his current choices in life.

His first job was in the law firm of Donald L. Hollowell, an eminent black attorney who was handling many of the breakthrough legal cases that would desegregate colleges around the state. He was, says Julian Bond, "Georgia's Thurgood Marshall. . . . For Vernon to be associated with his firm was a real plum, and meant Vernon was a comer, and was on his way—not in terms of riches, but in terms of being in line for a lifelong, illustrious career in civil rights."

Hollowell and an Atlanta civil-rights organization had recruited two young black students, Charlayne Hunter and Hamilton Holmes, to apply to the University of Georgia, in the hope of creating a case that would force the state's compliance with the Supreme Court's ruling that public education must be desegregated.

It was Jordan who, in weeks of digging, found the final bit of evidence that countered the university's stalling tactics—identifying a white student who had been accepted in spite of a set of circumstances identical to the ones the admissions committee claimed stood in the way of Hunter's admission. In January 1961, a federal judge ordered that the students be admitted, and it was Jordan who escorted them through a surly crowd for their enrollment.

From Hollowell's office, Jordan went to work for the N.A.A.C.P. as the Georgia field director. It was the first of a series of jobs that would characterize him as a member of the more conservative, administrative end of the movement. In the early 60s, the venerable N.A.A.C.P. was criticized by members of younger, more aggressive groups such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, and even by Martin Luther King Jr.'s more moderate Southern Christian Leadership Conference.

But it would be unfair to see Jordan only as an N.A.A.C.P. bureaucrat who played it safe. Says Bond, "Part of his job involved going into these little rural towns where there was some danger in being a black man in a suit, let alone a black man from the N.A.A.C.P. Being seen in a suit, driving a car, in some of these little counties where everyone knows each other, was a real act of courage."

From the N.A.A.C.P. he moved to the Southern Regional Council, and then to the Voter Education Project, which was begun under the council's auspices. Funded by New York-based foundations, it was a Kennedy-inspired program started in 1962 to channel the civil-rights movement's efforts in a way that would keep racial strife off the front pages of the newspapers and, as a happy by-product, produce hundreds of thousands of new Democratic voters. Jordan's term as director of the project, from 1965 to 1970, may constitute his most lasting legacy to the civil-rights movement.

Taylor Branch, author of Parting the Waters: America in the King Years 1954–63, was hired by Jordan as a graduate student to work for the project. He observes, "It was unglamorous scut work—registering voters in the South—at a time when everyone else had turned into a revolutionary or a business executive. There was a terrible irony: that the Voting Rights Act had finally been passed [in 1965], and all the people who had sacrificed and risked so much were running off to join the Black Panthers. There was no one to follow through. Vernon was one of the few leaders who stuck with it. . . . When he worked for the Voter Education Project, which is when I knew him up close, he didn't really fit the image you hear a lot of people knock him with."

If it was laborious work, it was also the beginning of Jordan's exposure to the world of foundations and corporations. Having revealed his gifts as a fund-raiser, Jordan was lured north in 1970 to be executive director of the United Negro College Fund. But he had served less than two years when Whitney Young, the longtime leader of the National Urban League, drowned during a trip to Nigeria. Jordan, only 35, was asked to succeed him.

Jordan became a national figure there—and an accomplished corporate politician. The Urban League had always been the black organization most closely allied with business, reaching back to the days of its founding, before World War I; its original mission was to alleviate the poor living conditions of urban blacks, with special emphasis on job training and placement. And after the racial violence of the late 60s, corporations and the federal government were more ready than ever to strike alliances with a moderate group that could speak their language.

Jordan was brilliant at exploiting this. He was so good at raising money that the group's operating budget doubled in the 10 years he was director. And he became well known among corporate C.E.O.'s at precisely the time that they were beginning to understand that they would have to integrate their boards of directors. In his decade at the Urban League, Jordan was invited to join the boards of R. J. Reynolds, Xerox, American Express, Celanese, J. C. Penney, and Bankers Trust.

Increasingly, Jordan's social circle and his aspirations lay with this corporate world. He lived in New York, in a co-op on Fifth Avenue overlooking Central Park. His approach—while outwardly more political, more aggressive in advancing a civil-rights agenda, than the League had been in the past—was sometimes criticized for being too attuned to the concerns of the black middle class, at the expense of the poor. But the grumbling was kept in check by Jordan's undoubted dynamism. He had developed a high visibility for himself and for the League at a time when the news media were looking for a way to explain the fractured civil-rights movement; Jordan—handsome, well connected, with a large and respectable organization as his platform—was a media darling.

During his time at the League, Jordan faced two personal ordeals. The first was the decline of his wife, Shirley, who had been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1965, only seven years after the couple married and when their daughter, Vickee, was only five. By the late 70s, Shirley could no longer get around without a wheelchair. "She held on to the end," recalls Commerce Secretary Ron Brown, who worked with Jordan at the Urban League. "She resisted, resisted going in a wheelchair. She wanted to do as much for herself as she could. .. . [But] in the end she became very dependent on him." She fought the disease until 1985, when she died at the age of 48.

"That's very personal," Jordan says, when asked to discuss it. "That was a major trauma for our little girl, for me, and for her. But you do what you have to do in this life, and so you make all of the necessary adjustments, sacrifices, to see to it that she could live as normal a life as possible—and she did that."

The second crisis of his 40s was as sudden as a sniper's bullet. On May 29, 1980, at two o'clock in the morning, Jordan was shot by a rifleman in the parking lot of a Marriott hotel in Fort Wayne, Indiana. It was an astonishing crime, for racial hatreds had cooled somewhat from their peak in the previous two decades, and, in any case, Jordan was not the sort of leader who had ever really incited those passions.

At first, the police suspected that the shooter's motive had been personal: at the time of the attack, Jordan was getting out of the car of a white woman, an attractive, four-times-divorced local Urban League volunteer named Martha C. Coleman. He had had cocktails with Coleman after giving the speech that had brought him to Fort Wayne; at one o'clock in the morning, they told police, they had left in her car to have coffee at her house.

Though Jordan and Coleman told the police that they had spent less than half an hour at her house, the circumstances were such as to suggest that some disgruntled lover of hers might have tried to kill him.

Ultimately, however, the local police and the F.B.I. developed strong evidence that the shooting had been a racial attack by a stranger. The Justice Department indicted an avowed racist named Joseph Paul Franklin on charges of violating Jordan's civil rights. By the time of his trial, Franklin was serving four life sentences for the murders, committed three months after the Jordan shooting, of two black men he had seen jogging with white women in Salt Lake City. But though many of those involved in the Jordan case—including Jordan, up to the present day—felt that Franklin was indeed the shooter, he was acquitted for lack of evidence.

Jordan, who suffered a wound the size of a small fist just an inch from his spine, spent 98 days in the hospital. Today he bats away questions about the shooting. "There's only one thing to say about being shot and that is I woke up this morning and put my feet on the floor and that's it, that's history." On his doctors' advice he saw a psychiatrist for a few months. "He is convinced and I was convinced that I was not traumatized by it," Jordan says. "I don't dream about it, I don't think about it, I have no bitterness, and I am not afraid."

Even before the shooting, Jordan had grown restless in his work at the Urban League. It was a staggering idea, to other black leaders, that Jordan should want to quit such a high-visibility job. He sensed, however, that his power base as a civil-rights leader might be parlayed into a different kind of power on a wider stage. There were still two worlds, and the idea was still to get to that other one.

Jordan asked his friends Walter Wriston, then head of Citicorp, and C. Peter McColough, then head of Xerox, to put out feelers to law firms in New York and Washington. McColough mentioned Jordan's ambitions to Robert S. Strauss, the Washington lawyer-lobbyist and founding partner of the Texas-based firm Akin, Gump. Strauss jumped at the chance to hire Jordan.

Akin, Gump is one of the most aggressive firms in Washington at plying the seam between the public and private sectors. It has more than two dozen partners who are registered as lobbyists, for clients ranging from AT&T to Burger King, from the governments of Colombia and Chile to Japan's Fujitsu and Matsushita, from the Motion Picture Association of America to the National Football League.

The firm's Washington practice was built largely on the strength of Strauss's ties to political figures. A relentless self-promoter who has backslapped his way to the status of Washington power broker, Strauss served as Democratic National Committee chairman from 1972 to 1977 and as U.S. trade representative in the Carter era. That Akin, Gump is a highly political firm is attested to by its fundraising: for example, in the 1990 election cycle—through both individual donations and the firm's political-action committee—it gave more money to federal candidates than any other law firm in the country, according to an analysis by the Center for Responsive Politics.

From the moment Vernon Jordan arrived in Washington, he made it quite clear that he was breaking with his past: "He said, 'I ain't no civil-rights leader anymore,' " recalls Eleanor Holmes Norton. " 'I'm not going on television to talk about it anymore; that's for people whose job that is.' "

Jordan told another friend, in the early 80s, "When I left the Urban League, I determined that I would do nothing for the next 10 or 15 years but make money for myself." Adds this friend, dryly, "He came to the right place in Strauss's firm."

Jordan earns, according to informed speculation, legal fees of close to a million dollars a year. In addition he earns handsome board fees. To the boards on which he already sat (minus Celanese, of which he was no longer a director), he added six more after joining Akin, Gump: Dow Jones, Corning, Sara Lee, Union Carbide, Ryder System, and Revlon. Assuming Jordan attends all scheduled board meetings, as well as meetings of board committees on which he serves, his fees, according to information compiled by the nonpartisan Investor Responsibility Research Center, amount to at least $504,000 a year.

Jordan's wife, Ann—a former professor of social work at the University of Chicago whom he married in 1986—is herself on five corporate boards: Capital Cities/ABC, the Hechinger Company, Johnson & Johnson, National Health Laboratories, and Primerica. Her board fees add a potential $202,600 to the family's annual income.

When he retires, Jordan's boards will pay him at least $160,000 annually for the following 15 years. And he controls stock worth more than $1.5 million in all the companies he serves. A final benefit of Jordan's board service is in the legal work he scares up for Akin, Gump. Of the 11 companies he is associated with, 6 are clients of the firm.

But what exactly does Jordan do for his law firm? His major clients include American Airlines and Mazda; his major areas of concern are variously described as mergers and acquisitions and, in the words of a partner, "counseling clients who have problems in which Washington plays a substantial role." He has also, on at least one occasion, put his civil-rights background to use for a client: when the Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Association went to war against a proposed law that would have cut Medicaid costs by mandating the substitution of generic drugs for more expensive name brands. As part of Akin, Gump's lobbying campaign against the proposal, orchestrated largely by Jordan, groups representing minorities argued that the proposal would consign those minorities to inferior medical care.

But Jordan is registered as a lobbyist on only one account, American Airlines. Typically, men like Bob Strauss and Vernon Jordan easily slip through the porous lobbying-disclosure laws. While lobbyists for foreign interests are required to register with the Justice Department, and those who lobby senators or House members must register with an office in Congress, no one need register in order to lobby for a domestic client before any agency of the federal government. And even in areas requiring registration, someone at Jordan's level isn't necessarily reflected in the records. "Guys like him, they don't like doing legislative work much," says a former colleague. "So they'll outline the strategy, and then some associate will go up and do the work."

"The tricky thing about rainmakers is you never can really tell what they do," says Charles Lewis, executive director of the Center for Public Integrity. "They don't have to register anywhere; all they do is meet with people."

The presumed expertise of men like Strauss and Jordan is not in any legal skill but in their supposed great knowledge of Washington, their "judgment" on corporate affairs. "Vernon does not do a lot of heavy lifting, to put it mildly," says one person close to the firm.

"If you have some notion that I spend a lot of time in the library," says Jordan, "that is not the highest and best use of my time. . . . I don't need to do that—there are people who do that for me."

Echoes Strauss, "Vernon and I are never going to be great lawyers. Vernon sure wasn't brought in here because we wanted him to read the fine print of the law."

Still, a rainmaker has to deliver. And in his early years at the firm, Jordan was something of a disappointment, according to a 1986 article in The American Lawyer. "He was not quite as big a star as he was expected to be," says one former colleague. But over time his reputation improved. Firm members learned that he was a gifted stroker of clients and a talented contributor to the internal politics of the firm, and they elected him to the management committee in 1991.

Jordan's association with Bill Clinton clinched his importance. "Of course, now they're thrilled with him," says one source about Jordan's partners. "Now they all think he's the greatest thing since sliced bread."

He may be especially crucial in light of Strauss's recent miscalculations. Once known as "Mr. Democrat," Strauss dealt with 12 years of Republican rule by assiduously courting Reagan and then Bush. When, in 1991, he accepted Bush's appointment as ambassador to the Soviet Union, it looked like a canny move: the 1992 election was shaping up as a debacle for Democrats, and a role as senior diplomat would be a good alibi for his absence. When Bush bombed and Clinton unexpectedly succeeded, Strauss returned to Washington eager to drop the phrase "my law partner Vernon Jordan."

If it is hard to pin down the precise nature of Vernon Jordan's law practice, that fact is itself a key to understanding him. The role of any lawyer-lobbyist is amorphous, based at least half on perception; in addition to selling his clients' wishes to the federal government, he is also selling his client on the idea of his own omnipotence within Washington.

And Vernon Jordan has an especially rich lode of symbolic weight to offer. So rich that in many parts of his life it is enough for him simply to be Vernon Jordan, going the places he goes and seeing the people he sees. Knowing Jordan, being associated with Jordan, is a commodity with a particular value in each of the spheres he occupies—social, corporate, and political.

In September 1990, Jordan was a guest at a surprise 45th-birthday party for Michael Boskin, the chairman of Bush's Council of Economic Advisers. Held by former "Wonder Woman" Lynda Carter and her husband, attorney (and later B.C.C.I. figure) Robert Altman, it drew a predominantly Republican crowd: a few Republican senators, a smattering of media, and a handful of Bush Cabinet members, such as Jack Kemp.

Kemp stood to give a toast, which led him to talk of his eye-opening experiences as HUD secretary. In the last year, he remarked, he had probably been to more public housing projects than Vernon Jordan.

"And Vernon," recalls one observer, "with that great booming voice, yelled from the back of the room, 'And I don't intend to go!' "

It is a story that illustrates something of Jordan's special function in the world of Washington society. For Washington is two cities, the federal city and the local one. The federal city, and the ingrown social life that revolves around it, is overwhelmingly white, but the city onto which it is grafted is mostly black, with a government that is almost universally black. "Washington is an extremely segregated city," notes Peggy Cooper Cafritz, a black civic activist married to a prominent white real-estate developer. Most social events in white Washington, she says, include only "somewhere between 1 and 10" African-Americans.

As he paraphrased his Bohemian Grove speech to a friend, "just because you invite some nigger to this place, that doesn't let you off the hook."

Most of those who live in white government circles exhibit a sort of anxious resignation about this. Their culture is fundamentally a liberal one, and they have a nervous feeling that they should do better. Thus they speak about Jordan with an enormous relief, even gratitude. He is their exception, their touchstone.

He is their black friend.

"It's very hard to have good black friends in this town," says a very prominent Washingtonian. "It damn well is. ... I mean real friends: people you see, where you go to their house. And Vernon is that to a great many people."

Says a well-known woman, "There was a period in the 60s when everyone socialized with blacks to show how hip they were. They invited all the blacks they knew to parties, and made sure to kiss them and touch them. And it was all artificial. . . . So then in the 70s and early 80s, everybody pulled away from that. Like, 'O.K., we've proved we're liberal—let's just do what we're comfortable with.' " The result was a return to the all-white dinner party. "And then along came Vernon. And it was clear he knew how to speak the language—not just the white language, but the Washington social language. He'd say, 'I was talking to Liz and Felix [Rohatyn] last week...' "

Ann Jordan, she adds, "can talk about Porthault linens and buying a little Chanel bag."

In other words, the Jordans are seen as the class equals of anyone in Washington. "People feel grateful, because they feel that they're not racist, but that it really is hard," continues the woman. "There's a wall of glass between blacks and whites socially. And with the Jordans, you feel that you're their peer, a social equal—there's no barrier there."

Vernon Jordan would not be nearly so valuable in this role were he not a certified civil-rights hero. Some of his Washington friends were a little shocked when Jordan's transition service caused newspapers to write about the full extent of his board work: they treasure the idea of Vernon Jordan as a man still fundamentally devoted to good causes, and the knowledge that he served not on 4 or 7 but on 11 boards suddenly colored his life a bit differently. It is precisely because his image touches such extremes—the civil-rights movement and the company of Liz and Felix—that he is in a position to bring comfort to the guilty members of the liberal elite.

Jordan's role in corporate boardrooms, where he is the only African-American on all but one of the boards he serves, is similar. According to a recent study by the Connecticut newsletter Directorship, blacks hold 222 seats on the boards of the Fortune 1,000 companies, out of a total of 9,592; Jordan occupies a staggering 5 percent of those seats.

Some of Jordan's detractors complain that his board service is merely a form of tokenism. It is a fact that, in the words of compensation expert Graef Crystal, the typical C.E.O. looks to stock his board with "10 friends of management, a woman, and a black." But Jordan's achievement, for better or worse, is that on those boards where he sits, he is not only the single black but also one of the club—a friend of the C.E.O.

Only a member of the club would find himself a guest at California's exclusive all-male Bohemian Grove gathering. In July 1991, he gave the annual lakeside talk, choosing civil rights as his topic. "Business does not come to the debate with clean hands," he said. "I sit on enough corporate boards and enjoy the friendship of enough corporate executives to know that there isn't a company in the nation that can be satisfied with its hiring and promotions record."

Or, as he paraphrased the speech to a white friend back in Washington, "just because you invite some nigger to this place, that doesn't let you off the hook."

But it's not clear whether, for the corporate chieftains who thronged around the lake, this constituted anything more than a ritual shriving. Says Leslie Dunbar, who was once Jordan's boss at the Southern Regional Council, "I think somehow or another they know they can take their medicine from Vernon, and then afterwards they can share a drink with him."

In Barbarians at the Gate, their account of the leveraged buyout of RJR Nabisco, authors Bryan Burrough and John Helyar paint an unflattering portrait of Jordan as a board member concerned more with his own benefits than with the long-term interests of the company.

Jordan raises this before I do. "There was a suggestion in Barbarians that I was a patsy for C.E.O.'s. Well, that's just bullshit," he says. "I've never been a patsy for anything or anybody. . . . They don't know what the fuck they're talking about."

On six of his boards, he sits on the public-responsibility committee or its equivalent, which puts him in a position to ride herd on the companies' equal-employment policies. And Harry Freeman, formerly a top executive at American Express, says Jordan was very aggressive. "It wasn't lip service. He would say, 'How are we doing on minorities? What are the latest statistics on minority recruiting, and how do they match the statistics on minority population?' He would say, 'Have you tried X, Y, or Z college?' "

These efforts are in keeping with other efforts he makes in the context of his legal work. He is chairman of the National Academy Foundation, a private group that promotes corporate involvement in urban high schools. He is said to be a generous counselor of young black professionals. He chairs a forum created by the D.C. Bar to promote the advancement of minorities in the city's law firms. And in 1990 and 1991 he logged long hours trying to broker cooperation between corporate America and the civil-rights community in supporting a new civil-rights act.

To his fans, he seems to have struck the ideal balance between doing well and doing good: "Don't misunderstand me," says Dunbar. "Vernon is quite prepared to benefit personally. But I don't believe there is any position he's ever held that he has not tried, usually successfully, to make his situation in that job of benefit to other blacks."

But others point out that those efforts tend to go toward helping blacks who already have a surfeit of opportunity. "The only people he helps now are the ones already on the ladder. The talented 10th," says Cathy Hughes, the controversialist host of a black-oriented D.C. radio talk show. "It's the 90 percent who are not the exception that the Vernon Jordans of the world don't reach back and touch."

Jordan sees himself as holding "emeritus status" in the civil-rights movement. "I'm not a general, but I'm still in the army. And you can't leave the army, in a sense. . . . I am not so assimilated that I have lost my sensitivities to the basic inequities confronting minority people in this country."

But, finally, aren't there bound to be conflicts in the heart of a man like Vernon Jordan? I tell him that I am mystified by the apparent lack of tension in his life, the contradictions that show no ripple on the surface, if they are experienced as contradictions at all.

He shrugs, steeples his hands on his spotless desk, and smiles his most radiant smile. "Well," he says finally, "I can't help you with this mysss-ter-y."

The answer to the riddle may be more interesting than simple hypocrisy. To a young black boy growing up in Atlanta, working for white people while living and fixing his aspirations among black people, it was a fact of life that different standards applied in the two worlds he inhabited. It wasn't wrong to bow to this knowledge; there was, ultimately, a kind of authority in playing your role in the white community well.

The facility for filling separate, even contradictory, roles is not something Vernon Jordan learned recently. But he has put it to great advantage in his career. And in choosing to go to Washington, and, more recently, into Democratic politics, he may have found its highest use.

Vernon Jordan met Bill and Hillary Clinton some 20 years ago. His friendship with Hillary was cemented by their joint work on the board of the Children's Defense Fund, while he and the future president kept in touch the way ambitious politicians will do.

Perhaps they recognized that they are somewhat similar: Like Jordan, Clinton is the product of a matriarchal home that propelled him up from the lower middle class. Like Jordan, he is a man skilled at, perhaps, addicted to, the seduction of everyone he meets. And like Jordan, he is a real liberal, except when he's not—a complicated mix of personal ambition and purer motives.

When Clinton decided to run for president, Jordan was an early and fervent supporter. He developed an informal advisory role in the campaign, which led to his appointment as transition chairman.

Once again, he was not the man hired for the heavy lifting. As the transition unfolded, the most important work was done in Little Rock, under director Warren Christopher's efficient managerial eye. What Jordan did do, back in Washington, was serve as Bill Clinton's ambassador-at-large to the strange new country Clinton had conquered: charming the television cameras, stroking the reporters—infinitely reassuring, no matter what kind of reassurance you were looking for. When women's groups became upset at the way the Cabinet was taking shape, Vernon was the man to soothe them. When certain congressional leaders needed assurances that Clinton would not muck with this or that prerogative, Vernon was the man to pass the message.

"He's the show horse and [Christopher] is the workhorse," said one sharp-eyed Democrat during the transition. "He's like the expensive greeter at the restaurant. ' '

And there was a larger message being sent, on a grander scale than the day-to-day stroking of interest groups and egos. Clinton's campaign had brilliantly balanced the tensions that have pulled at the Democratic Party since the late 70s—between its low-income constituents and its high-income donor base, between its populist, liberal character outside the Beltway and its wealthy, business-oriented power structure within Washington. Now that the campaign was over, Vernon Jordan was the wink and the nod—the sign, from the new president to the Old Guard, that he understood their culture and would not combat it.

This was precisely what distressed reformists observant enough to understand the appointment's meaning. "I'm not saying Vernon Jordan is the worst guy who ever walked," says Charles Lewis of the Center for Public Integrity. "I'm just saying it was disappointing. . . . My objection to Jordan is that he is part of politics as usual."

While there were dozens of men (and they are all men) who might have provided the same kind of reassurance Jordan gave to the barons of Washington, there were none who carried the same aura of liberal probity. Jordan, with his elastic persona, his sure touch for the extremes of American society, was the perfect symbol for the new president. For Clinton ran on the proposition that a party could embrace extremes as great as those Vernon Jordan has lived out, and he hopes to govern by the same assumption.

As the transition went on, Clinton's disinclination to disturb the mores of Washington became even more obvious. Among his permanent appointments were several people with lobbying portfolios far more controversial than Jordan's, notably Ron Brown as commerce secretary (with former clients including the government of Haiti under Jean-Claude Duvalier and a host of Japanese corporations) and Mickey Kantor in the role of U.S. trade representative (with former clients ranging from Philip Morris to Lockheed, Martin Marietta, and Occidental Petroleum).

Why was Vernon Jordan not among Clinton's Cabinet picks? For some weeks he was widely thought to lead Clinton's shortlist for attorney general. Was entering the administration ever a serious possibility? "Sure, it was in question," Jordan replies. "I spent some time being titillated by the governor. Then I went down to Little Rock. . . and had a great conversation with Bill and Hillary and we worked it out. That's all I'm going to say." It's the practiced answer of a pro: just enough to convince the listener that he was a serious contender; not enough to be pinned on if in fact he was never offered the job.

Washington speculated that Jordan didn't want the hassle and potential embarrassment of a confirmation hearing, didn't want to take the cut in pay, and— most plausibly—didn't want to cut himself off from the corporate world in which he has such a singular role.

But all of this speculation somewhat missed the point. Jordan can continue to be an adviser to Clinton, a message bearer to and from the White House, a member of that famous club of men who earn, to their own tremendous profit, the Washington sobriquet of "wise man." The point is: Vernon Jordan already has a job in the new administration.

No comments:

Post a Comment