Even from “the back of nowhere, far from any city” – not to mention the sea – John Archer caught wind of the sea shanty revival before anyone else.

From his home in landlocked Ōhakune, Archer had noticed a sharp uptick in visitors to the New Zealand Folk Song website he set up in 1998. One 19th-century seafaring epic was of particular interest: Soon May The Wellerman Come.

Views of Archer’s highly-detailed, lovingly-compiled entry for the shanty unexpectedly spiked in late September, with most coming from the US. “I thought, ‘that’s strange’,” says Archer, a former schoolteacher who first set up NZ Folk Song as a teaching resource. “I knew nothing about TikTok.”

From “no visits at all” for most of last year, Archer’s Wellerman writeup has now drawn nearly 10,000 views in seven days, driven by the sudden resurgence of sea shanties on TikTok – widely reported on this week with a tone of faint surprise.

Nathan Evans, a 26-year-old postman and aspiring musician from outside Glasgow, is credited with having started the “ShantyTok” trend with his rousing rendition of Wellerman, posted in late December.

In the US and UK, Wellerman’s surprise popularity is being held up as evidence of the mental toll of months-long lockdown – but the shanty itself originates from the Antipodes, and tells of a pivotal point in Australia and New Zealand’s history.

A “Wellerman” was an employee of the Sydney-based Weller Brothers’ shipping company, which from 1833 was the major supplier of provisions – such as the “sugar and tea and rum” of the shanty’s refrain – to whaling stations on New Zealand shores.

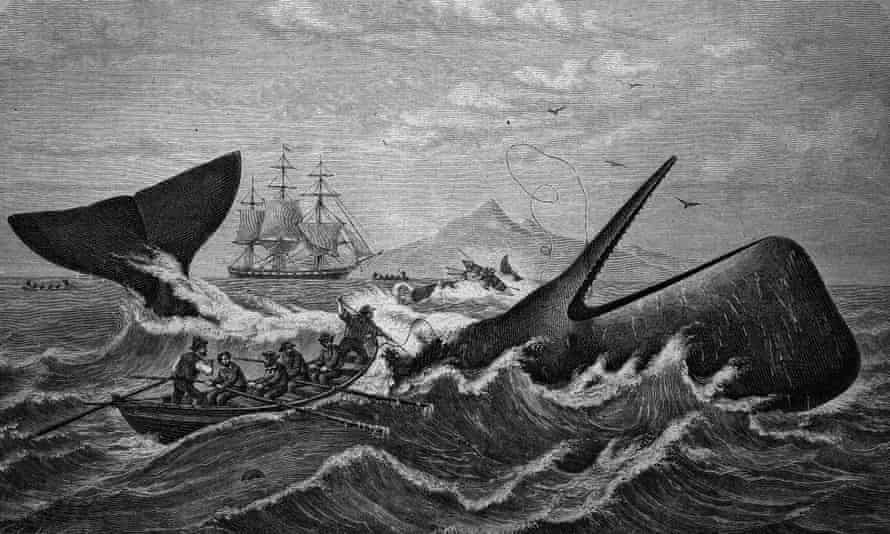

The whalers’ wistful eye on a future date “when the tonguin’ is done/We’ll take our leave and go” refers to the practice of stripping blubber from beached whales.

ShantyTok is taking the wellerman to increasingly more amazing levels! pic.twitter.com/9Bouf1IEN3

— Sly lil´ Vix ~🦊 Foxxie (@EidolonFox) January 12, 2021

The brothers Joseph Brooks, George and Edward Weller emigrated from Folkestone, Kent, to Sydney in 1823 and within 10 years had established themselves as the region’s preeminent merchant traders.

At the time, whaling was a prime export industry of New South Wales while, in New Zealand, the Wellers’ whaling station base at Ōtākou on the Otago Peninsula was the first enduring European settlement of what is now Dunedin city. (Their ship, the Lucy Ann, also went on to be crewed by one Herman Melville.)

But by 1841 the Wellers’ business had collapsed. As Ronald Jones writes in Te Ara national encyclopaedia, that period of seafaring industry “slipped unobtrusively out of the pages of New Zealand history” – preserved only through song.

Wellerman’s six verses tell the epic tale of a ship, the Billy of Tea, and its crew’s battle – “for 40 days, or even more” – to land a defiant whale. With the struggle ongoing at the shanty’s end, “the Wellerman makes his regular call, to encourage the Captain, crew and all”.

Archer suggests that it is the shanty’s “cheerful energy and hopeful outlook” – in contrast to other more “dreary” whaling songs – that has led to Wellerman’s rediscovery on social media.

“My guess is that the Covid lockdowns have put millions of young [people] into a similar situation that young whalers were in 200 years ago: confined for the foreseeable future, often far from home, running out of necessities, always in risk of sudden death, and spending long hours with no communal activities to cheer them up.”

mentally i'm here pic.twitter.com/IlinXkqcTH

— ˗ˏˋ Hayley DeRoche ˎˊ˗ (@hayleyderoche) January 13, 2021

Its embrace by TikTok is an unexpected 21st-century twist in a folkloric tradition that can be traced through New Zealand’s past.

Neil Colquhoun – a New Zealand folk music pioneer, who died in 2014 – first documented Wellerman in 1966, from a man then in his 80s who said he had been taught it by his uncle. Researching that link led Archer to shanties published in The Bulletin paper in Sydney in 1904.

His Google “guesswork” suggests Wellerman’s composer was a teenage sailor or shore whaler around New Zealand in the late 1830s, who penned the ditty on settling in Australia then passed it down within his family around the turn of the century.

From there, the shanty is believed to have spread around the world by its inclusion in Colquhoun’s book Songs of a Young Country, published in England in 1972. “I was singing it with others in folk clubs 40 years ago,” says Archer.

And now Wellerman is being circulated further by Spotify by way of its new “sea shanty season” playlist, celebrating “centuries-old songs gone viral”. That recording, by Bristol group The Longest Johns, is showing 8.5m recent plays.

The rising tide of ShantyTok has reached New Zealand shores, too. The Wellington Sea Shanty Society recorded Soon May The Wellerman Come on their 2013 album, Now That’s What I Call Sea Shanties Vol 1, and again in 2018. It is now receiving 30,000 streams a day on Spotify.

Guitarist and vocalist Lake Davineer says it has long been a floor-filler – second only to Drunken Sailor – at their shows. “Before all this happened, it was still the big banger that ended our set… It’s just a great tune.”

But, Davineer adds, their Wellerman is “more of a party version” than the traditional styles favoured by TikTok. “We do a big psychedelic intro.”

No comments:

Post a Comment