on

By the time photographer Josef Koudelka began photographing Roma communities across Europe in the late 1960s and 70s, “an ambitious drive to assimilate all Roma people into society had already begun,

At 15, Mikey Walsh left a Gypsy community in England in which he had been raised. He later published a memoir, Gypsy Boy, detailing the horrific abuse he suffered at the hands of his father and uncle. The portrait of his former culture is terrifying, and his judgment upon his people, devastating. “The Gypsy race is an old-fashioned and, sadly, a very bitter one,” Walsh concludes. “They live, breathe, sleep, grieve, love and care for only their own people. They don’t like or trust the ways of others and don’t have contact or friendships with other races, afraid that one day they will be forced to turn their backs on their once proud way of life and become like any other.”

Fear of outsiders is framed as pathology in Walsh’s account, but viewed in a wider context, it seems like an entirely justified response to centuries of persecution at the hands of “other races.” The epithet “Gypsy,” given to Roma people by outsiders, has long been associated with criminality. Portrayals like the 1928 German Expressionist film The Man Who Laughs –based on Victor Hugo’s novel of the same name – cast Romani as “child-buyers” (Comprachicos, a word invented by Hugo), who intentionally mutilate and deform children to use them as beggars and entertainers. It’s a seriously frightening idea, especially in relation to the real traumas Walsh describes in his memoir – and it is largely an invention formed of centuries of stereotyping.

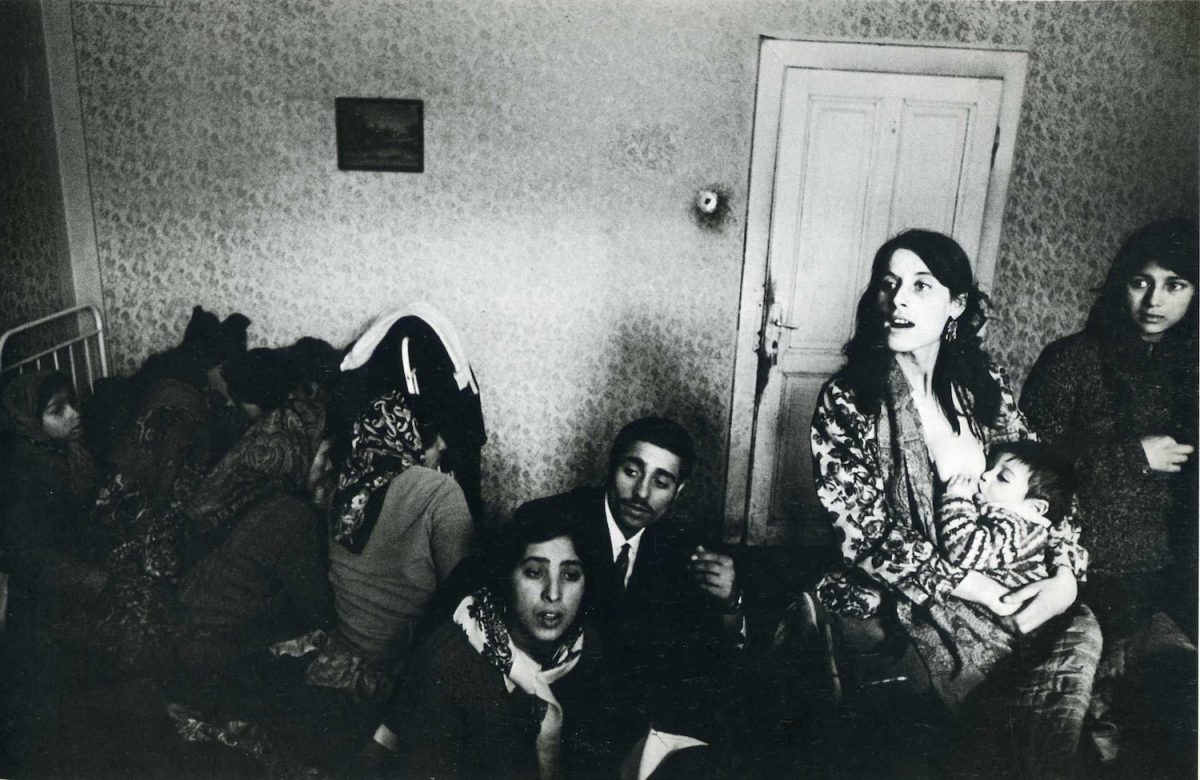

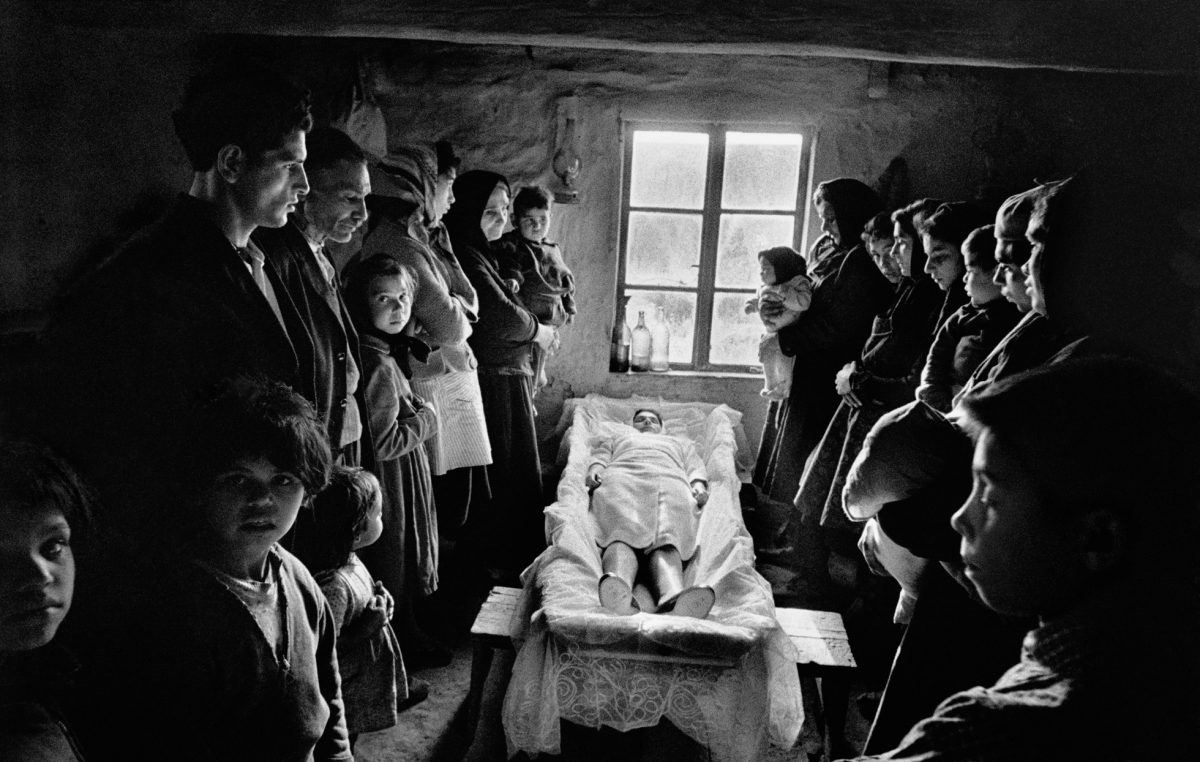

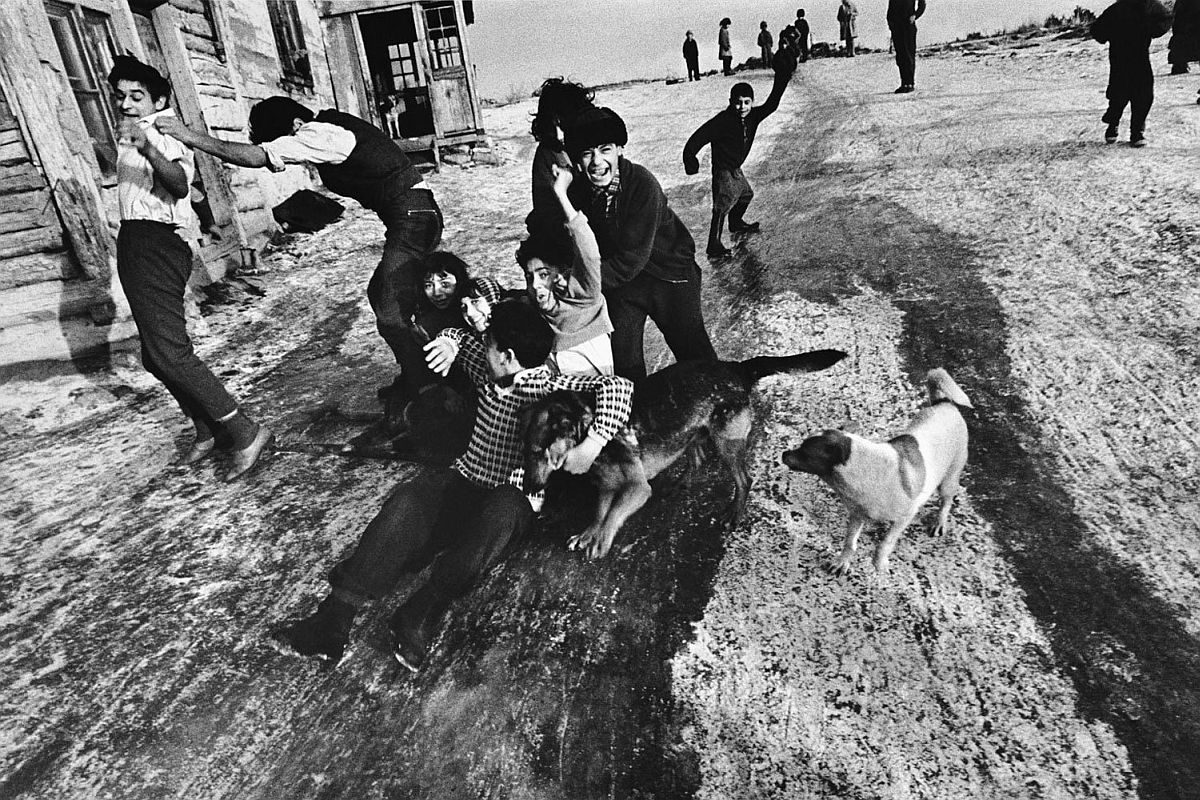

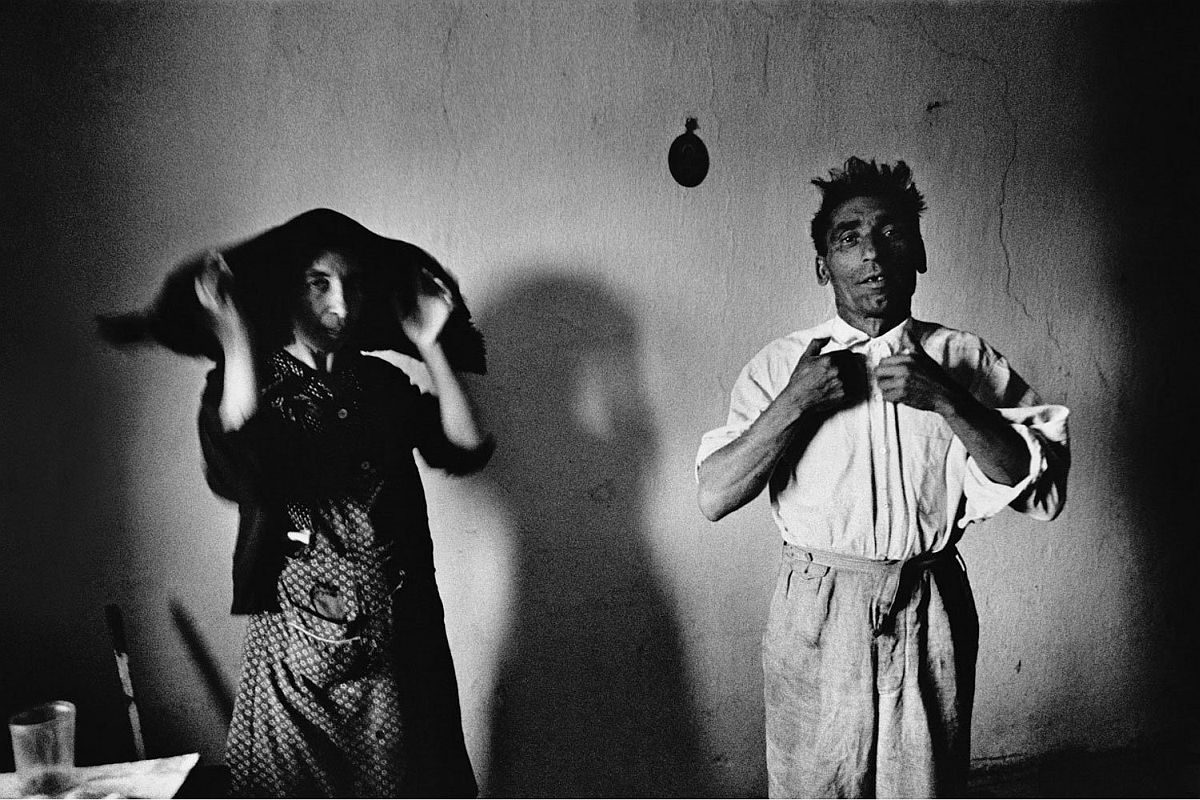

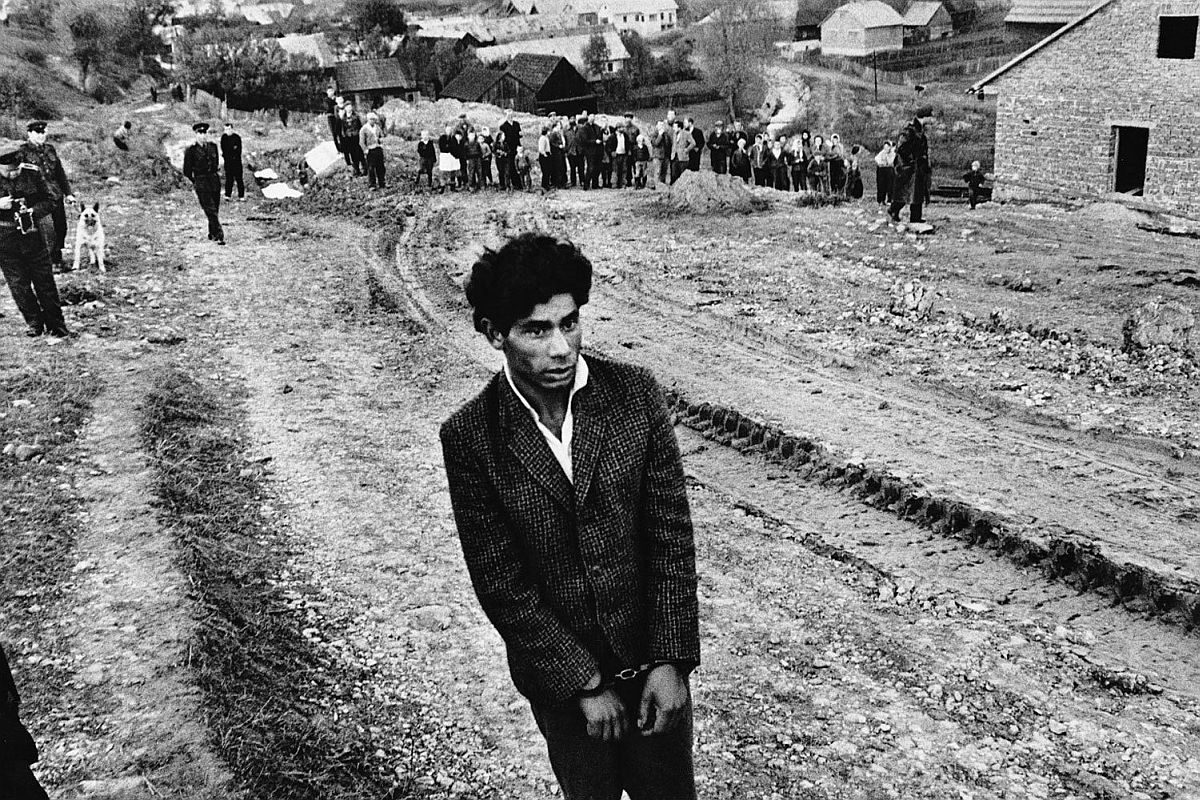

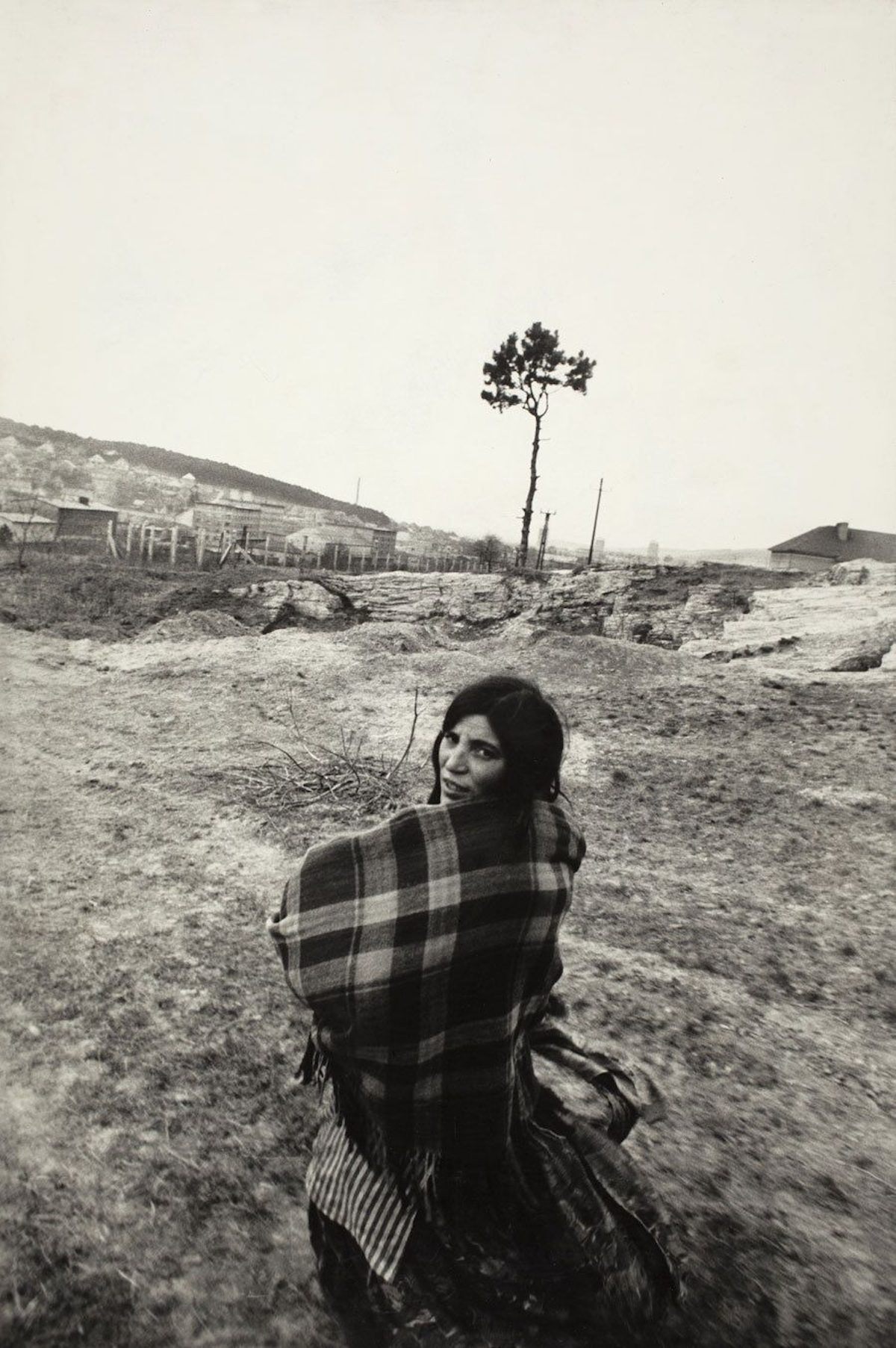

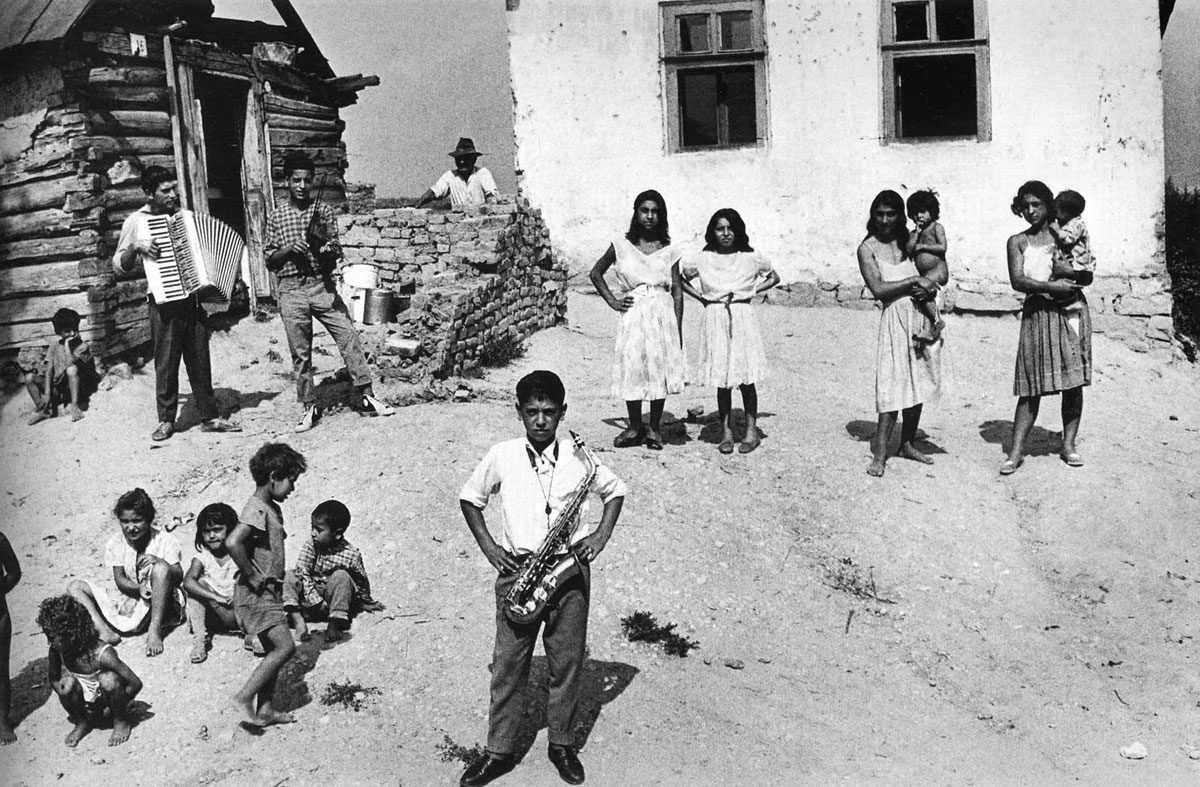

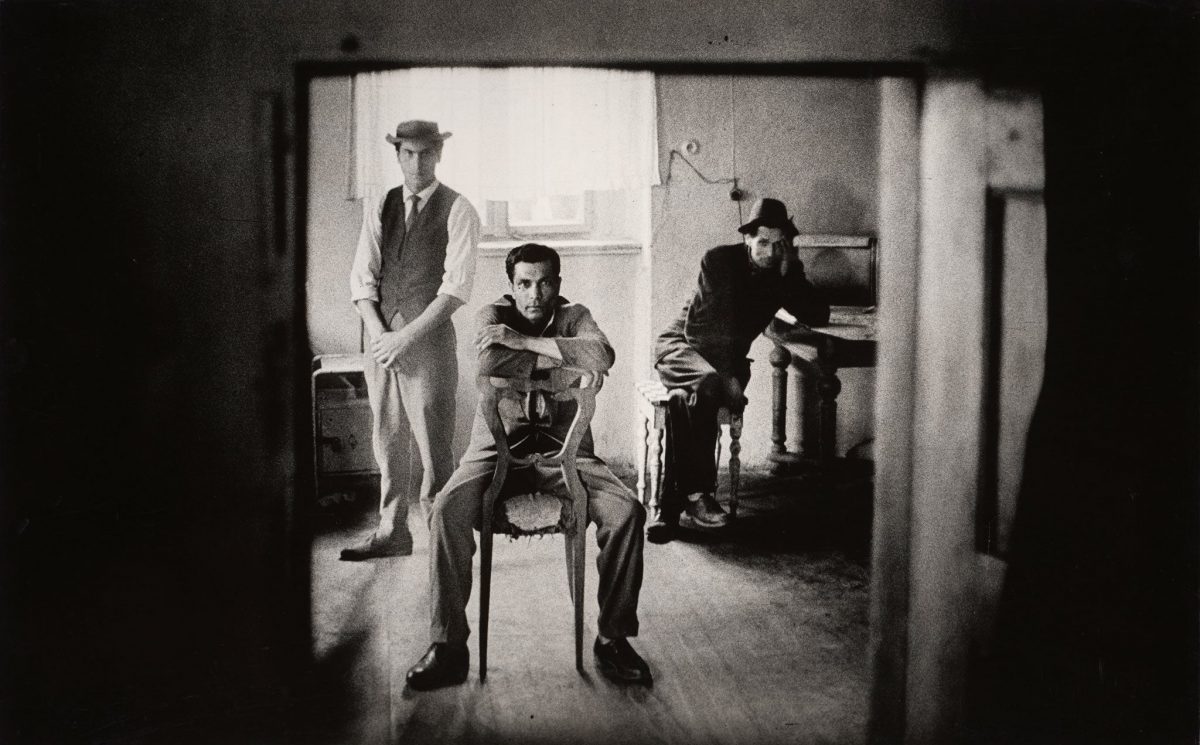

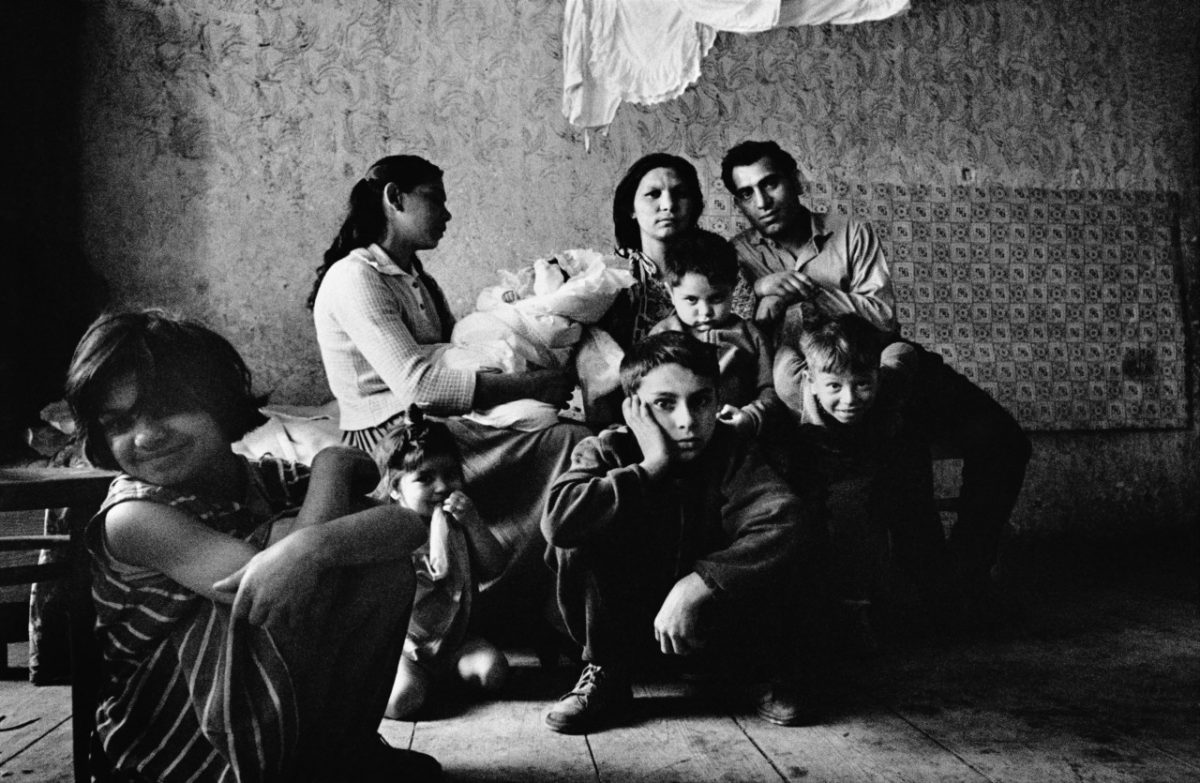

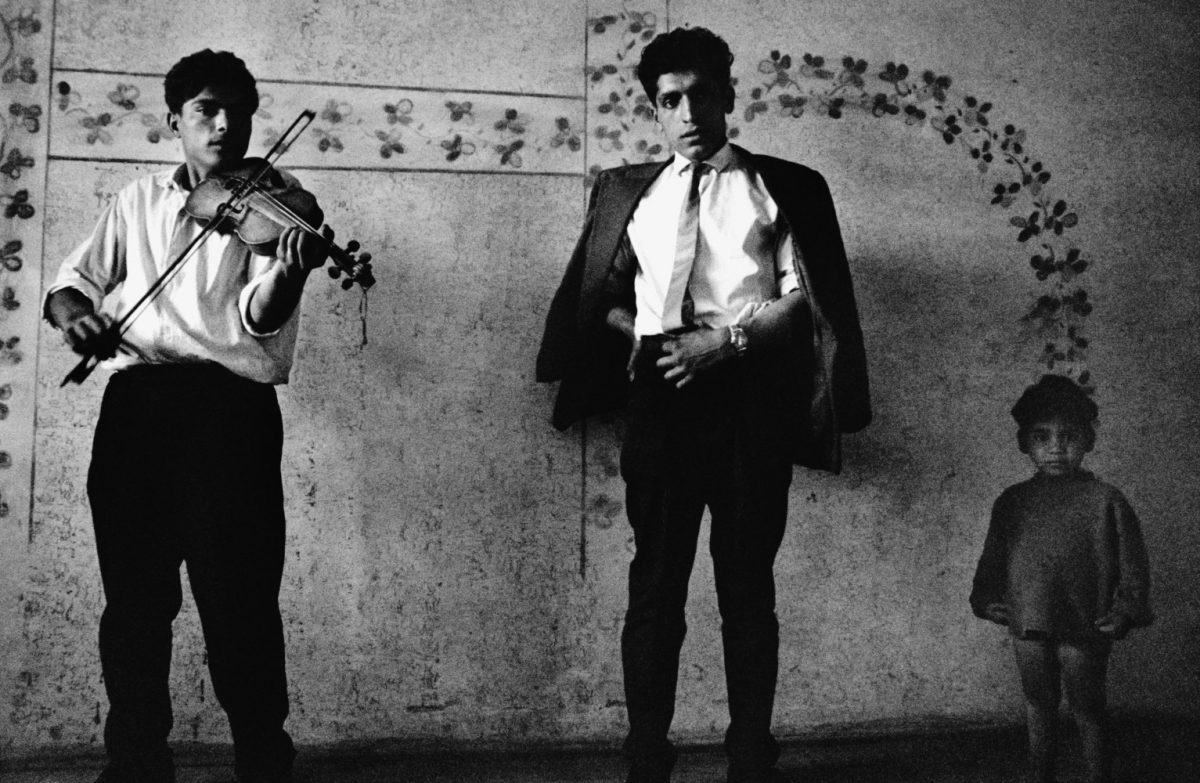

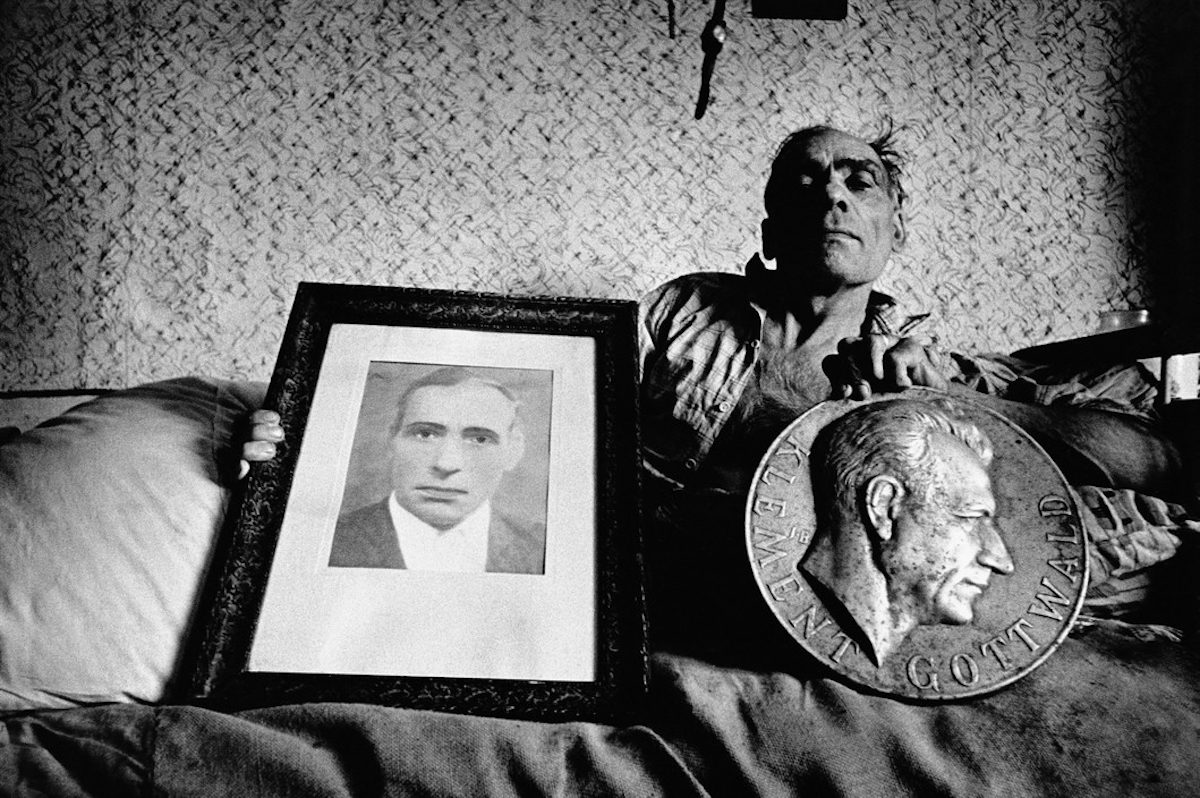

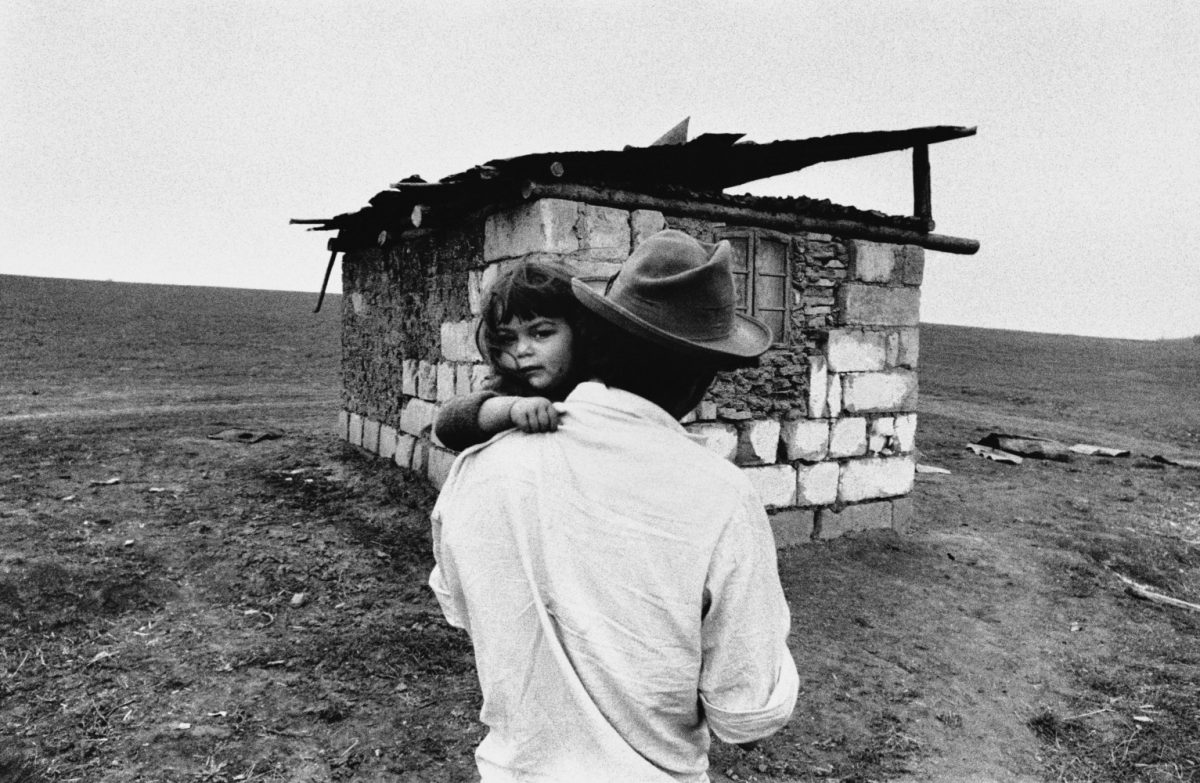

As Communist governments took control of much of Eastern Europe after the war, conditions promised to improve. However, by the time photographer Josef Koudelka began photographing Roma communities across Europe in the late 1960s and 70s, “an ambitious drive to assimilate all Roma people into society had already begun,” writes British Journal of Photography editor Hannah Abel-Hirsch. “Persistent efforts to undermine and eradicate their identity, although mostly failed, were deeply humiliating” and relied upon the same stereotypes that cast the Roma as undesirables.

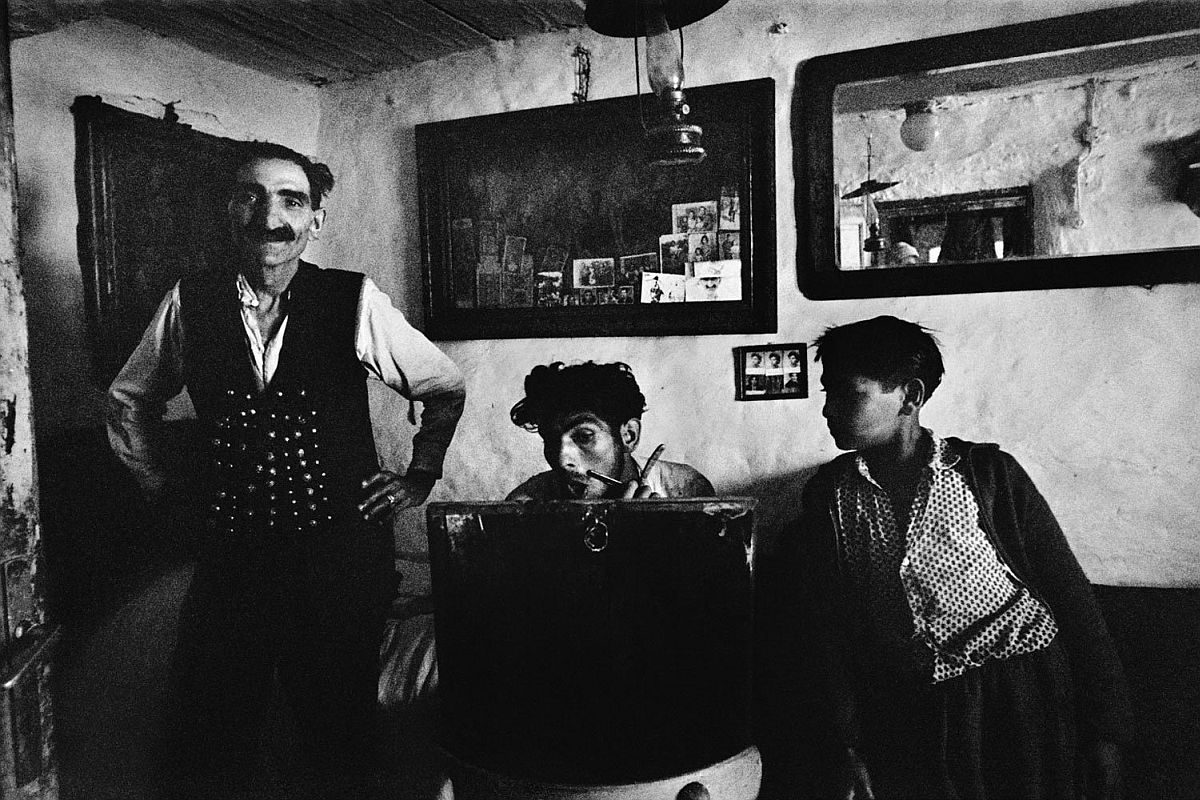

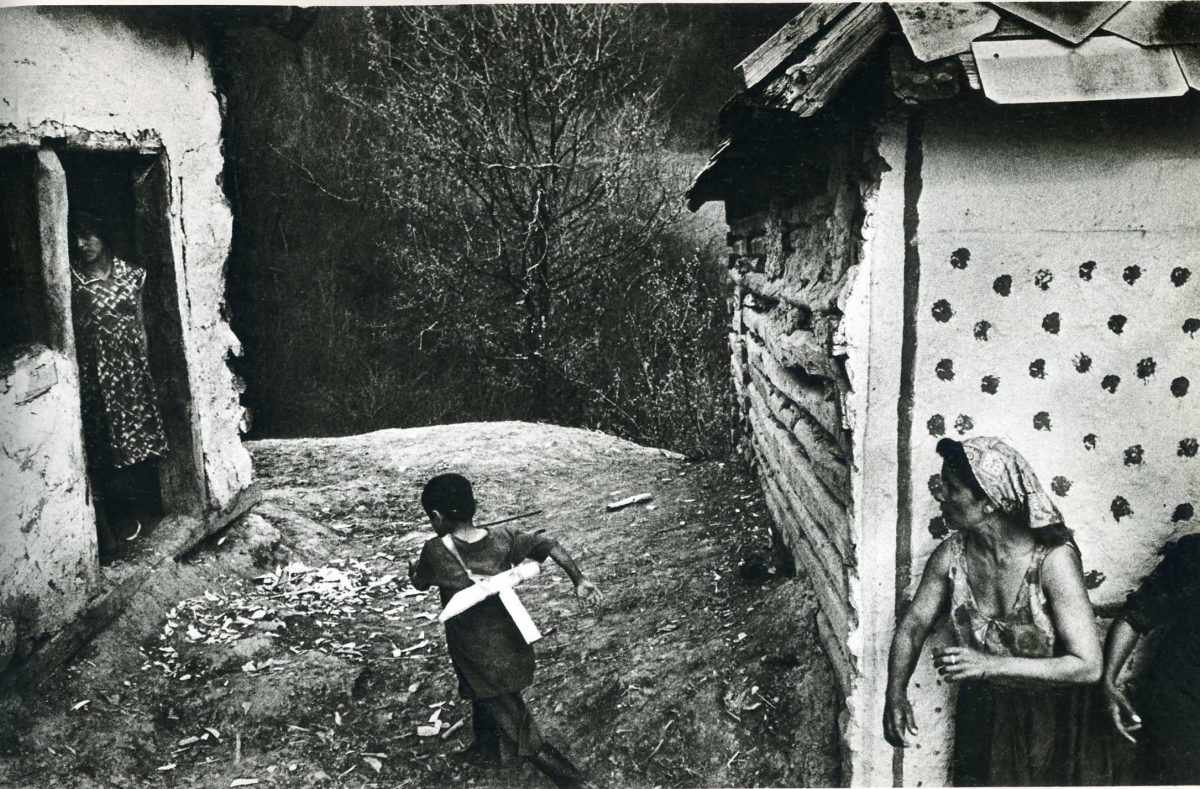

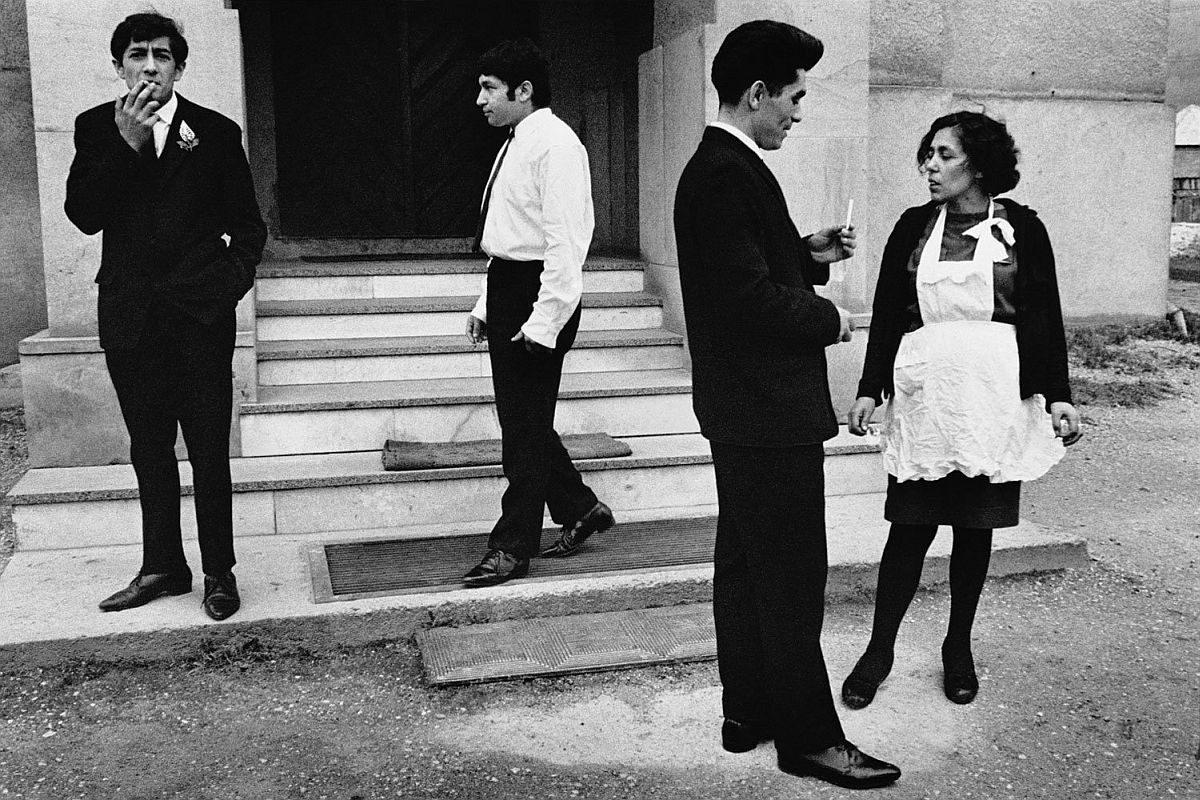

Koudelka, who fled his native Czechoslavakia in 1968 after coming to fame for his images of the Prague Spring, first conceived his project in the early 60s as a way of changing those ancient prejudices. From 1962 to 1971, he traveled Czechoslovakia, Romania, Hungary, France, and Spain with a single backpack, following Roma caravans and sleeping outside their camps or on the floor in villages in a sleeping bag. Koudelka later enlisted the help of sociologist and Roma expert Will Guy, “who wrote the texts for the first and subsequent editions of Gypsies,” the collection of these photographs first published in 1975. “Koudelka’s determination to present the Roma community without ethnizing their poverty,” notes Bayryam Bayryamali at Magnum photo, “propelled him to search for intimacy between friends and family, lovers and relatives, cousins and neighbors, in his photographs.”

Koudelka’s humanizing scenes addressed “the absence of family portraiture of Roma in the public sphere.” The project serves as a visual correlative to other long-term attempts to combat Roma stereotypes, such as the publication, since 1888, of British research journal The Gypsy Lore Society. The photographer “believed from the outset that his images alone would not present the complex reality of his subject’s lives,” but like Dorothea Lange, whose famous Depression-era images underscored the humanity in poverty and social marginalization, he believed in the power of “showcasing emotive images alongside factual accounts of sociopolitical realities.”

No comments:

Post a Comment