PeaceData, seemingly a leftwing news outlet, offered me a column. I should have known it was too good to be true

On 8 July, I was contacted via direct message on Twitter by a man who introduced himself as an associate editor for PeaceData. @Alex_Lacusta described his organization as a “young, progressive global news outlet that was seeking young and aspiring writers” and was looking to grow its presence on social media. Would I want to write a weekly column and be paid $200 to $250 per piece?

My interest was piqued. I had lost my part-time job in the food industry amid the economic fallout of the coronavirus pandemic, and I was in need of income and an outlet to build my portfolio. The opportunity to write a column could be the break I was hoping for.

Yes, I thought it was odd that an international media group would be reaching out to me since I had limited national exposure in the media. However, one of my pieces for the non-profit news organization Truthout on the Trump administration’s response to Covid-19 had gained traction on social media. I assumed this was how I was discovered.

In his initial email introduction, “Alex” reduced the rate to between $80 and $150 per piece, but he argued I’d be able to write columns about topics I was interested in as long as the pieces were focused on “anti-war, anti-corruption, abuse of power, or human rights violations”. Given my prior work, I was comfortable with these issues, and I wrote on similar issues for reputable outlets.

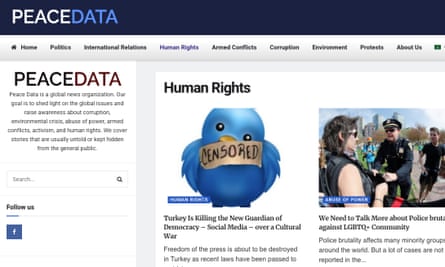

Before accepting, though, I read the articles that had been published on the site and researched a couple of their editors and writers. At a glance, the articles seemed up my alley. They were critical of US foreign policy and the Trump administration. Other contributors appeared to have verified Twitter accounts with tens of thousands of followers. That PeaceData had writers with verified Twitter accounts appeared to legitimize the operation.

I’d end up writing three articles for PeaceData, and there were some oddities in the process.

On 22 July, I noticed Alex’s Twitter account and the account of another PeaceData editor, Albert Popescu, had strikingly similar profile pictures and were recently created. At the time I recall thinking this was bizarre, yet chalked it up to coincidence and the fact this was a new “publication”. In my email correspondence with editors, words that should have been singular were plural or a preposition would be occasionally omitted. The errors weren’t widespread, and it wasn’t the first time an editor had sent me a note with typos. And unlike other writers for PeaceData, I didn’t experience suspicious editorial suggestions and the editors’ thoughts on angles for my stories seemed reasonable.

One occurrence did shake me, though, and led me to distance myself from PeaceData. By this time I had been paid by two separate PayPal accounts – about $100 per article. I was told my first article was republished by GlobalResearch, a site I was unfamiliar with. About a week later – between the launch of my second article and my final submission – I was torturing myself by reading incoherent QAnon conspiracy theory posts on Twitter and noticed that QAnon-related accounts were sharing links from GlobalResearch.

On the GlobalResearch home page, I found several conspiratorial articles promoting hydroxychloroquine as a Covid-19 treatment, as well as 9/11 truther articles and pro-Vladimir Putin content.

I started looking into other articles posted by PeaceData and noticed one defending Belarus’s dictator, Alexander Lukashenko. It was disturbing and didn’t align with my values. I realized that the opportunity with PeaceData was too good to be true and decided not to write for them any longer.

On 25 August, the day my final piece for PeaceData was posted, I learned that Twitter had suspended the editors and the main account. It made me start connecting the dots. But I hoped for the best – that they were just sloppy or disorganized.

One week later, I received another DM on Twitter, this time from a reporter telling me that PeaceData was potentially part of a Russian disinformation campaign. According to Facebook, US law enforcement had provided a tip that PeaceData was connected to “individuals associated with past activity by the Russian Internet Research Agency (IRA)”. (In a post on its website, PeaceData says Facebook “baselessly” accused it of working with Russia.)

I was shocked and confused, but as soon as I read about it and talked to reporters, the red flags and weird occurrences began to add up. I had been completely unaware of PeaceData’s links to the IRA and Russian oligarchs. I wish this had never happened and I’m not proud to be associated with it. I’ve lost sleep because of it. I have been confused, embarrassed, and frankly angry at myself for letting the potential for a break get the best of my judgment. It isn’t flattering being linked to an authoritarian regime’s media operation. It’s even quite ironic for a progressive anti-authoritarian committed to transparency who has argued that Trump and Putin are cut from the same reactionary cloth.

This has been a defining event that I do not intend to repeat. It’s given me an up-close understanding of how easy it is in journalism today for entities to exploit underpaid workers, making them unwitting agents for nefarious or unclear interests. My initial advice to media consumers is to always be on guard when interacting with content and users on social media. I would have never guessed I would be caught up in a dubious media campaign. And as I process this, I can’t help but think that it’s important to recognize that in this competitive, politically charged and consolidated political and media environment, this probably won’t be the last time something like this will happen.

No comments:

Post a Comment