The New Yorker, April 28, 1997 P. 150

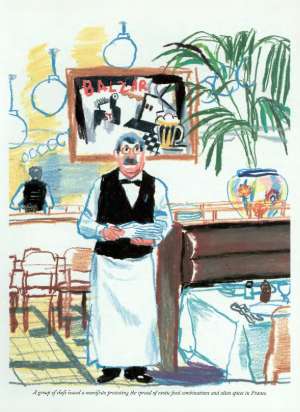

THE POLITICS OF FOOD about the state of French cuisine. The great chef Alain Passard, of Arpege, is known for a dessert for which his commis, David Angelot, spends hours stuffing and braising tomatoes in caramel. Passard's technique is unlike anyone else's: he cooks his meat on the stove over extremely low heat for hours. Most people who love Paris love it because the first time they came they ate something better than they had ever eaten before. Gopnik had this experience twenty-five years ago, at dinner with his family in a little brasserie. That first meal was always one of the few completely reliable pleasures for Americans in Europe. Now, for the first time in several hundred years, people are worried about French cooking. This is partly a tribute to its influence, to the great catching-up that has been going on in the rest of the world. The fear is that the muse has migrated to Berkeley, with occasional trips to New York and, of all places, Great Britain. Gopnik would still rather eat in Paris than anywhere else. The problem may be the French genius for laying the intellectual foundation for a revolution that takes place elsewhere. The historic leaders of French cooking were Antonin Careme, known for "presentation," and Auguste Escoffier, whose invention of the master sauce is still the basis of haute cuisine. It was an article of faith that their styles had evolved from provincial techniques, like the pot-au-feu. Eugenio Donate, a post-structuralist critic, believed that "French cooking" was an invention, a series of "metaphors." The more abstract and self-enclosed haute cuisine became, the more its lovers pretended it was folk art. Meanwhile, the food grew inedibly rich. The "nouvelle cuisine" that replaced the old style created a fundamental revolution. The new cooking divided into what Donate labelled "two rhetorics," soil and spice. But the great leap forward has stalled. There is the expense: the cooking at top places in Paris has become like grand opera in the age of the microphone. Lunch at Lucas Carton today is Napoleonic, Empire. At lesser places, the style is formulaic: meat, complement, sauce. Donate said the new French cooking was not a revolution but only a reformation. The American cooks who followed in Alice Waters's footsteps created a freewheeling, eclectic cosmopolitan cuisine. In France, the soil boys dominate: last spring, a group of important chefs issued a manifesto protesting exotic food and alien spices. Some of what they stand for is positive: an organic, earth-conscious element. The real national dish of the French -- the cheap, available food -- is couscous, but North African cooking remains segregated. A fossilized metropolitan tradition should have been replaced by a modernized one, not sentimental nationalism. The invasion of American fast food made the French want to protect their own tradition. Alexandra Guarnaschelli, a young American cook in Paris, discussed their rigidity. American restaurant manners -- "I'll be your waiter tonight" -- are democratic. The French system of education locks people in place. A new book, "L'Amateur de Cuisine," by Jean-Philippe Derenne, is an anatomy of French cooking. It is an eleven-hundred-page volume, comprehensive and radiant; Derenne considers it a religious book. A hundred years ago, his expansive, open, embracing ardor would have seemed more American than French. Perhaps the different fates of the new cooking in France and America are a sign of a new relation between them. Americans were once drawn to the Old World by the allure of power, and fascinated by the self-consciousness that came with it. Now that power has passed into American hands. Gopnik decided to go back to his first restaurant, and found it not far from the Avenue Marcel-Proust. It is now called the Tournesol. Gopnik ate a la carte; the food was even better than he had remembered -- a hopeful sign

No comments:

Post a Comment