George Prescott Bush was just sixteen when he first took the political world by storm. The year was 1992, the setting the Republican National Convention at the Astrodome in Houston, where his grandfather would be nominated for reelection as president. On the third day of the convention, Barbara Bush, looking matriarchal and resplendent in a pearl necklace, invited her clan on stage, “all twenty-two of them.” There was P.’s uncle George W. Bush. His dad, Jeb, and his mom, Columba, who had met in her native Mexico when they were still in their teens. And a lot of young grandchildren, including a tot wearing an Enron hat. But the speaking slot was reserved for just one family member: “George P., our eldest grandson, from Miami, Florida.”

Young P. had the awkward swagger of a sixteen-year-old boy, but he delivered his lines with conviction. “In a presidential campaign, it’s hard for people to get a sense of what makes the candidates tick. The family is what makes my grandfather tick,” he said. Later, after he finished reading excerpts from a letter from his grandfather, the crowd broke into a chant: “George P.! George P.! George P.!” Jeb beamed. Seconds later, P.—named after his great-grandfather, U.S. senator Prescott Bush, from Connecticut—wrapped it up, improvising “¡Viva Bush!” and a fist pump. A star was born.

The next decade would see the full flourishing of the Bush dynasty. George W. would parlay his tenure as Texas governor into the presidency. Jeb would become governor of Florida. And P.? By the time he spoke at the 2000 RNC, slipping Spanish into his speech as handmade signs in the crowd declared him a “hunk,” he had become the face of the family’s future. He was young, bilingual, and handsome, with a world-class smile, and was the subject of gushing press coverage. His grandfather had been the forty-first president; his uncle was about to be the forty-third. Some family insiders would soon be calling P. “forty-seven.”

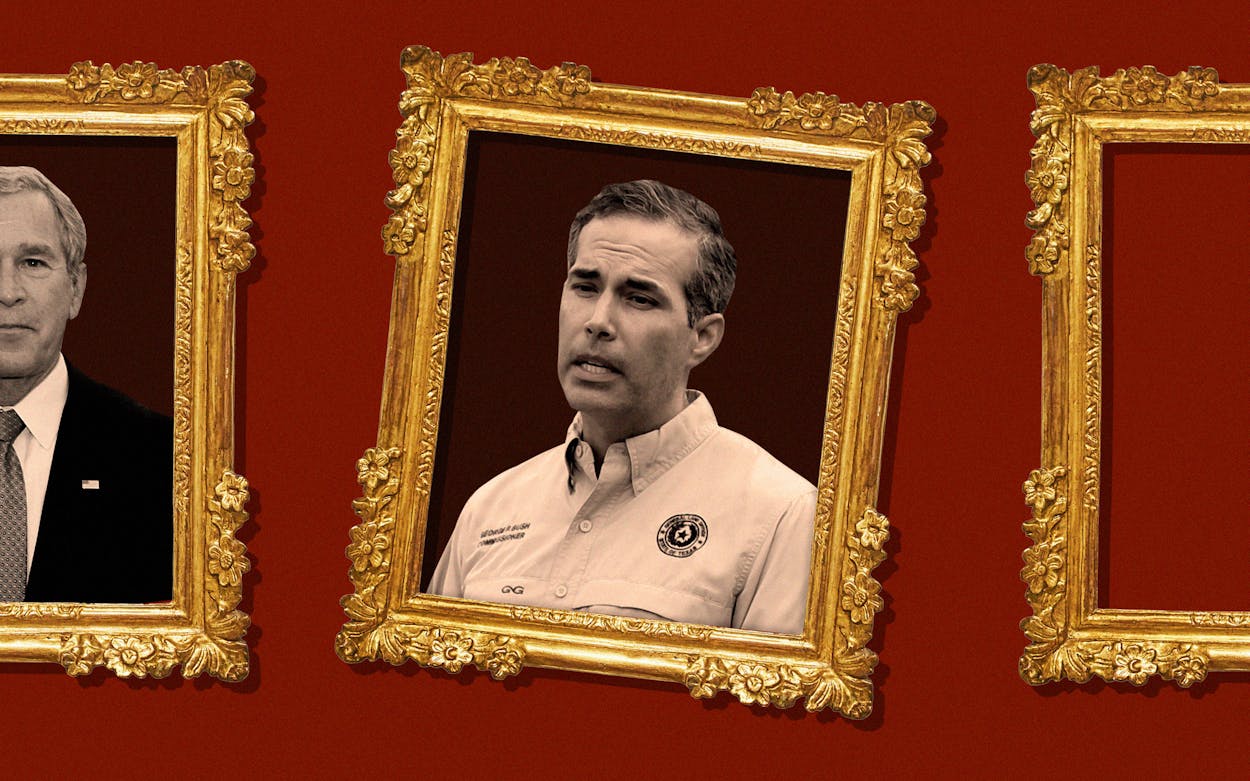

But two decades later, the Bush dynasty is hanging by a thread. George W. is spending his post-presidency painting portraits of military veterans and immigrants. Jeb is an almost-forgotten punch line from his humiliating 2016 campaign for president. And 2018 saw the death of George H. W., the paterfamilias whose passing occasioned nostalgia in some quarters for a more genteel era of Republican politics. The third or fourth generation—but who’s counting?—has not been as politically potent as previous ones. When Pierce Bush, P.’s cousin, ran for a Houston-area congressional seat in 2020, he came in a distant third in the GOP primary. Barbara and Jenna and Jebby Jr. have evinced little interest in the family business. If there is a future for the Bush brand, it must be carried by the man H.W. once introduced as one of “the little brown ones.”

“George P. Bush has been working for many years to position himself as the next Bush in the line of succession,” said Bill Minutaglio, an Austin author who wrote one of the earliest books on the Bush family. “Now he may be the last fading gasp of the Bush political dynasty.”

After almost two terms as Texas land commissioner, a venerable but obscure statewide post, George P. is running in a chaotic, four-way GOP primary for Texas attorney general—a race that his spokesperson calls a “circus.” Bushes have always been good at remaking themselves to suit changing political tides, but P. faces a particularly daunting task. He has staked his fortunes on convincing Republican primary voters that he is loyal to his family’s number one tormentor, Donald J. Trump. He must count on voters seeing him as part of the GOP’s future, rather than an irritating reminder of a kinder, gentler, more establishment Republicanism.

The stage for this somewhat Shakespearean drama is a tawdry one. The office is currently held by Ken Paxton, the state’s almost comically corrupt top law enforcement official. Elected in 2014, Paxton has been under indictment for securities fraud for the last six and a half years, charges he’s managed to keep perpetually at bay through some nifty legal legerdemain. He’s also under investigation by the FBI for bribery and abuse of office after eight of his top aides went to the authorities with their concerns. Oh, and he cheated on his wife—a fact that became publicly known after Paxton’s aides said he asked a wealthy donor at the center of the bribery scandal to give his lover a job.

But the incumbent is a survivor. Like Governor Greg Abbott, the attorney general before him, Paxton has used the office to relentlessly sue the federal government and please the right-wing Republican base. Most infamously, he ingratiated himself with Trump and his followers with a lawsuit in December 2020 aimed at tossing out election results in four states that voted for Biden.

There are two other challengers. Eva Guzman is a distinguished jurist with a compelling story of working her way up from poverty in a Houston barrio to the Texas Supreme Court. Leaning heavily on her legal credentials, she has raised more money than her competitors, though she’s consistently polled in last place. The final entrant is Louie Gohmert, the wild-eyed, nine-term East Texas congressman whose name is synonymous with the angry, conspiracy-prone fringe. All three challengers have the same goal: hold Paxton under 50 percent on March 1 and get into a May runoff with the incumbent.

Bush, Gohmert, and Guzman are all warning that Paxton, if nominated, could face federal criminal indictment, potentially robbing Texas conservatives of a key battle station in the culture wars. The policy differences are slight. All four want to build the wall, crack down on the “illegals,” and banish critical race theory from Texas classrooms. These are largely hearts-and-minds campaigns, a competition to see who can conjure the MAGA spirit most convincingly.

Bush is in a tough spot. Trump has been insulting the Bush family for more than a decade. In 2013, as P. geared up his land commissioner campaign, the future president took to Twitter to call for “no more Bushes!” He repeatedly humiliated Jeb Bush in the 2016 campaign, dogging the former Florida governor as “low-energy” and a mama’s boy and reducing him, at one low point, to pleading with attendees at a campaign event to “please clap.” He has mocked George W. Bush’s “failed and uninspiring presidency.” As president, he bragged to Fox News about ending the “Bush dynasty.”

At first, when Trump emerged as a 2016 contender, P. seemed to put family first. Three months after Jeb dropped out of the race, P. was tapped to head up the Texas GOP’s statewide election strategy. But when asked if he would endorse Trump, P. initially said he couldn’t “because of concerns about his rhetoric and his inability to create a campaign that brings people together.” That summer, however, Bush changed his mind. In August, P. backed Trump’s presidential bid, albeit tepidly. “From Team Bush, it’s a bitter pill to swallow, but you know what? You get back up, and you help the man that won, and you make sure that we stop Hillary Clinton,” he said.

In the years since, P.’s stance has gone from awkward embrace of Trump to smothering bear hug. Fealty has had its rewards. Trump endorsed Bush during his 2018 reelection bid for land commissioner, and in 2019, at an event in Crosby, Texas, Trump enthused that P. was “the only Bush that likes me.” The quote resurfaced a couple years later—on koozies that Team Bush circulated at P.’s announcement party for attorney general. The internet was not kind. “This is ‘Please clap’ in koozie form,” said one wag on Twitter. For his announcement, Bush descended a staircase to greet his fans—a tableau vaguely reminiscent of Trump riding down the escalator in 2015 to announce his presidential campaign. Bush didn’t rant about Mexican rapists, but he offered a diluted version of Trump’s obsessions. P. complained about “open borders,” promised never to “apologize for backing the thin blue line,” and bragged that he was “the only member of the Bush family to endorse Donald J. Trump for president of the United States.”

If there were any doubts about the power dynamics in the relationship, however, Trump put them to rest a few months later, when he snubbed Bush by endorsing Paxton. Many questioned why Bush had bothered prostrating himself. After all, Trump’s warm embrace of Paxton made complete sense: the two men share a fondness for breaking norms and flirting with the outer limits of the law. Also, Trump had bragged about breaking the Bush dynasty. Was he really going to stand aside for its encore performance?

Paxton can certainly smell a whiff of desperation. In a recent fund-raising letter, headlined with Trump’s ringing endorsement of Paxton, he painted Bush as a fortunate son. Referring to P. twice as “Jeb Bush’s son,” Paxton wrote, “He’s probably been told since he was a child that his ‘destiny’ is to run for governor and then president.”

Some of P.’s earliest friends and supporters found the courting of Trump both disturbing and politically inept. Former Republican state representative Jason Villalba, a Dallas centrist who worked with Bush to recruit Hispanics into the GOP, said he counseled P. not to suck up to Trump too much. “I told him, ‘You’re never going to make those people happy.’ And even if Trump had endorsed him, I don’t think it would have changed one vote in Texas from Ken Paxton to George P. Bush.” Bush’s response? “He didn’t say anything. When someone tells you the frank truth like that, usually you don’t respond.”

The Alcove Cantina, a Mexican restaurant and bar in the historic district of Round Rock, a big Austin suburb, has a comfy outdoor patio area, complete with a stage and architectural touches from when the building was an ice cream parlor during Prohibition. It seemed a perfect setting for a small political gathering on a warm January evening during the worst of the COVID-19 omicron surge. But the George P. Bush campaign opted to hold its event inside, to better highlight the way pandemic restrictions had hurt Texas restaurants and bars.

About fifty supporters were packed into the bar to hear from the 45-year-old land commissioner. The crowd was a mix of Texas General Land Office employees, local Republican pooh-bahs, curious voters, a law enforcement official or two, P.’s wife’s cousin, and a college kid who told me he was there just to seek an internship with Bush and lamented that the GOP has “gone off the rails.” The event was part of Bush’s two-month cross-state push to connect with the grassroots and promote his “Texas First” agenda.

Bush’s delivery was typically polished, if a bit stiff. During his stump speeches, he toggles from talking up somewhat technocratic points about veterans’ programs at the GLO to darkly accusing liberals of the “wholesale indoctrination of our schoolchildren.” Like his father, Jeb, he doesn’t come across as having a tremendous fire in his belly, but the crowd was receptive enough to his promises to run the Texas attorney general’s office as a conservative without corruption.

In keeping with the GOP playbook in 2022, Bush’s not-too-subtle echo of Trump’s “America First” nationalism spotlights a martial vision of law and order: full-throated support for law enforcement and aggressive pushback against what Bush calls “deadbeat county DAs” and liberal mayors. But it’s the border that takes center stage.

“We’re going to focus on securing the border first and foremost,” P. said. “Joe Biden campaigned on the idea that he wasn’t going to build another inch of wall. Well, he’s right. We’re going to build miles and miles of Texas wall—and it starts on GLO acreage.” In January Bush pledged to have 1.8 miles of border wall built on GLO-owned land in Starr County by the end of the month. (When I checked back with the campaign in early February, a spokesperson said the completion date had moved to June.) He vowed that as attorney general he would “finish President Trump’s wall,” send attorneys from the AG’s office to the border to assist with prosecutions of border crossers, and sue the Biden administration over its “open border” policies.

If P. feels any regret about so nakedly seeking Trump’s blessing, he hasn’t shown it. His campaign literature features a photo of the two men shaking hands at the 2019 Crosby event and disingenuously touts P. as “an early endorser of President Trump.” When I asked him whether Trump’s snub stung, during a brief interview in Round Rock, Bush responded by saying, “Trump is the center of the Republican party; he’s the life of the party.” As to the pluses and minuses of the family name, he deployed a line he’s been using for two decades, one that his father used too: “I’m my own man.” He elaborated: “I obviously love my family, respect their service. They brought me into politics, the craziness of politics, but I’m my own man.”

If the Trumpist gambit is politically necessary, it’s also occasionally cringeworthy. One of P.’s ads shows him driving a four-wheeler alongside a section of border wall, an awkward image that has just a whiff of Michael Dukakis on a tank. (Strangely, the ad inadvertently depicts the futility of the wall; it includes footage of two men easily scaling the structure while wearing what appear to be heavily loaded backpacks.)

“George P. is Exhibit A of the challenge of being a legacy candidate in today’s Republican party,” said Mark McKinnon, a onetime close adviser to George W. Bush. “He gets the advantage of name ID, but all the baggage associated with being part of a pre-Trump dynasty. He’s trying to thread the needle, but the eye just keeps getting smaller.” Still, McKinnon added, “he’s got a lot of talent, and if anyone can pull it off, he can.”

While some have painted P. as a family turncoat, there’s another way of thinking about him—as the latest practitioner of the Bushes’ talent for reinvention. George H. W. Bush left Connecticut, and his blue-blood roots, and moved to West Texas to make his name and fortune in the oil patch. He began his career in electoral politics by running for the chairmanship of the Harris County Republican Party to prevent the John Birch Society from taking over, only to bring the far-right, anti-communist group into the fold after he won. When he ran unsuccessfully for U.S. Senate in 1964, H.W. knocked the liberal incumbent, Ralph Yarborough, for supporting the Civil Rights Act, even though he privately regretted taking a position that encouraged racists. In the 1980 Republican presidential primary, he was sharply critical of Ronald Reagan and his “voodoo economics”—but he moved to the right as soon as he got the nod for vice president. His son, hard-partying frat boy George W., became a brush-clearing born-again Christian, then governed Texas as a bipartisan champion of education before running the country as a staunch conservative.

Mark Updegrove, an Austin-based presidential historian who interviewed the two president Bushes for a 2017 book about their relationship, said the family has always hewed to an ends-justify-the-means political pragmatism. “The Bushes do what they need to do in order to obtain political power,” he said. “But when they exercise it, they do their very best to reflect their core values as a family and as Americans.”

Several P. supporters I spoke with shrugged off his Trumpian turn as just typical election-year politicking. What else was he supposed to do? And, of course, there’s a chance P.’s gambit will work. At the Round Rock event, I asked a supporter whether the Bush name did anything for him. “I don’t love dynasties,” he said. “And frankly, I don’t think the legacy is a great legacy.” With P. standing just a few feet away, he added, “Little Bush was a f—up,” referring to George W. “The idiot in Florida is still an idiot,” he said of P.’s father. But P., he said, “doesn’t seem like the predecessors.”

The groundwork for P.’s electoral career was laid over many years. After earning his undergraduate degree from Rice University, followed by a year teaching at an inner-city school in Florida, he received his law degree from the University of Texas at Austin. Then came brief stints as a corporate lawyer, real estate investor, and Navy Reserve officer with a tour of duty in Afghanistan. He and his family resided in Dallas, then Fort Worth, then Austin. In 2009 he helped start a political action committee, Hispanic Republicans of Texas, to cultivate Latino conservative talent. Along the way, Bush campaigned for his father and uncle and perfected his answer to the perennial question of when he himself would run. “It’s easy for a guy in my shoes to run for office,” P. said in 2005. “But I want to get there on my own merits, not just because I’m part of the Bush family or because I carry the name George Bush.”

Bush has claimed his earliest memory is from 1980, when he was four years old, standing onstage at some political event wearing a “Bush for President” T-shirt. (His grandfather lost to Reagan that year.) At age twelve, in 1988, he led the Pledge of Allegiance at the Republican National Convention. In 2000, eight years after his “¡Viva Bush!” speech, he hit the campaign trail for George W.—the handsome face and bilingual voice of a new, diverse GOP. “I’m glad to be introduced by the man in our family,” his uncle joked at a campaign event in 2000, “el hombre guapo, el estrella.” The press ate it up. People magazine named P. one of the nation’s hundred most eligible bachelors. He later did some modeling, and it became almost a media cliché to refer to P. as the Ricky Martin of Republican politics. “The Bush With Muy Guapo Appeal,” proclaimed a headline from the Los Angeles Times.

Early on, young P. seemed to understand his dilemma. The Bush name opened doors, but it could also be a burden. “It’s a kind of unwritten law, I think, carrying the name George Bush,” he told an interviewer in 2000. “At times I ask myself, ‘Am I going to be able to live my life the way I want to?’ I’m cautious about doing certain things.”

Caution is indeed one of P.’s hallmarks. Though his longtime allies and friends describe him as the most conservative Bush, his policy preferences have often been maddeningly vague. While campaigning for George W., he generally embraced his uncle’s brand of Republicanism and declined to elaborate on what parts he disagreed with. On immigration, P. favored comprehensive reform—a path to citizenship for undocumented immigrants, plus stepped-up border security—and he occasionally expressed a trenchant critique of U.S. policy. In 2004, when he went to Mexico to drum up votes among American expats for his uncle’s reelection campaign, P. described Border Patrol’s use of plastic pellet guns as “kind of barbarous” and blamed it on immigration agents acting “macho.” In one of his first brushes with the gathering anti-amnesty forces on the right, Michelle Malkin excoriated him for impugning Border Patrol agents.

Lesson learned. Seventeen years later, in 2021, when immigration agents on horseback provoked outrage after they were photographed aggressively confronting Haitian migrants in Del Rio, Bush, who has been endorsed by the Border Patrol union, rushed to their defense. He told Fox News that the Biden administration’s “attempts” to “disparage our Border Patrol are out of control.”

Bush’s formal entrance into electoral politics was cautious too. In 2012 he announced that he would be running in two years—but for which office he didn’t know. Trey Newton, a Republican operative who managed Bush’s first campaign, recalls the moment Bush told him about his plans: “It was kinda funny. He made this comment, ‘Hey, I think I’m gonna run.’ And I said, ‘Well, you’re a Bush; isn’t that what y’all do?’ ”

Late in 2012, his overeager dad perhaps jumped the gun by writing to supporters about P.’s interest in the General Land Office. He concluded by asking the potential donors to “write a personal check” to his son’s campaign.

The General Land Office oversees the $48 billion permanent school fund, various veterans programs, and Texas coastal issues. Once in office, Bush would take heat for self-deprecatingly comparing his post to “dogcatcher,” but entering politics at this level seemed to suit both his cautious nature and his long-term ambitions. He hadn’t wanted to run in a competitive primary, and Jerry Patterson, the sitting land commissioner, was stepping down at the end of 2014 to run for lieutenant governor. Prodigious fund-raising and the surname Bush cleared out any Republican competition.

By then, with comprehensive immigration reform a distant memory and the tea party movement in full bloom, P. had learned to finesse his more moderate views, if not bury them. His campaign website made no mention of immigration. When pressed by the Texas Tribune’s Evan Smith to state his position on immigration reform during a rare onstage interview in 2014, Bush explained that while he favored an “overall solution,” it was up to the feds to solve. When Smith kept pressing, he offered lukewarm support for in-state tuition for undocumented immigrants.

Bush had plenty to say, however, about national issues far beyond the purview of the GLO. As he talked up private school vouchers—a perennially pushed, perennially failed idea loathed by many rural Republicans—Bush came up with a novel triangulation, a sort of half-pregnant formulation: “I’m a full advocate for private vouchers in limited instances.” After conservative activists pounced on P. for seemingly acknowledging the existence of climate change, his campaign unfairly blamed a reporter for misrepresenting his views. None of it mattered all that much. Bush beat his Democratic opponent 61–35.

His tenure of the GLO got off to a rocky start. Soon after taking over the agency, he launched an ambitious, high-profile redevelopment of the Alamo. He took over management of the site from the Daughters of the Republic of Texas and partnered with the city of San Antonio on a plan to transform the site from a shabby tourist trap to a more respectful and historically informed destination.

For those deeply invested in the Alamo myth, the plan prompted about as much enthusiasm as Ozzy Osbourne peeing on the Alamo grounds. They saw the redevelopment as a harebrained desecration of the martyrs of 1836. In particular, a proposal to move the cenotaph—a 56-foot-high monument inscribed with the names of slain Texians and Tejanos, many of them misspelled—incensed a cadre of modern-day Alamo defenders, some of whom launched heavily armed protests.

In 2018 Bush had to fend off a challenge from Jerry Patterson, his predecessor. He won comfortably, but the scandal soured P.’s relationships with elements of the GOP grassroots. It confirmed, for some, a long-term suspicion: This guy isn’t one of us.

The other big scandal on Bush’s watch has arguably been more damaging: his handling of Hurricane Harvey recovery. In the aftermath of the 2017 storm—the most destructive in Texas history since 1900—Governor Abbott put Bush and the General Land Office in charge of long-term rebuilding. It was an opportunity to elevate the status of the agency, not to mention P.’s own profile, while doing something indisputably praiseworthy: putting Texans back in their homes and preparing for the next storm. But the recovery has been hampered for years by a series of controversial GLO decisions on how to distribute $2.1 billion in funds meant to build infrastructure to protect against future flooding.

Perhaps the most consequential came in May 2021, just a few weeks before the launch of P.’s attorney general campaign. Leaders in Houston and Harris County, which were particularly devastated by Harvey, reacted in horror when they learned how much they would be getting out of $1 billion earmarked for flood mitigation: nothing. The same went for the counties covering Corpus Christi, Beaumont, and Port Arthur that had been hammered by the storm. Instead, the GLO proposed sending every dime to rural communities in southeast Texas, many of which had suffered far less damage. A Houston Chronicle investigation found that the agency had devised a funding formula that punished populous areas—communities that happened to be predominantly Democratic, poor, and non-white.

Bush eventually agreed to ask the feds to send $750 million to Harris County; the city of Houston and the other populous coastal communities, however, would still get nothing. Then, last month, the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development announced that it was withholding nearly $2 billion in funding after civil rights and housing groups showered the agency with data they said showed that the GLO was discriminating against low-income Texans and Texans of color.

Bush has tried to variously blame the feds and Houston-area Democrats for the bad publicity. At the Round Rock campaign event, he said he had taken on “deadbeat liberal mayors,” an apparent reference to Houston mayor Sylvester Turner, who is facing accusations that he directed a Harvey-related housing contract to a favored developer. But Bush’s defense has been undercut by the fact that the outrage was bipartisan. Also in January, the two Republican commissioners on the Harris County Commissioners’ Court joined the Democrats in signing a letter urging the feds to bypass the GLO and hand the funds directly to the locals.

Of course, the opinions of local officials don’t count for much in today’s GOP. Though hard-right criticism of Bush has been muted this campaign season—Governor Greg Abbott has attracted most of the ambient rage of the anti-masking, anti-immigrant crowd—he hasn’t exactly inspired the activist element. His website lists over a hundred endorsements, about thirty of which are from relatively obscure local law enforcement figures such as Constable Mark “Maddog” Davison, Liberty County, Precinct Three. Virtually none are from the sort of hard-core grassroots leaders who propel the party.

Paxton, on the other hand, touts a solid list of endorsements from conservative clubs. For groups like the Collin County Conservative Republicans, the choice to support the incumbent was a no-brainer. “Paxton has done his job and he’s done it very well, and he makes liberals trigger,” said Zach Barrett, the president of the group. “They squirm every time he comes forth with a lawsuit.” Bush was never under serious consideration. “I don’t care for George P. He tries to separate himself from his family, but I’m done with the Bush legacy, I really am. The Bushes are really not conservatives. They are establishment Republican elitists.”

But it’s not clear the establishment is fully showing out for P. Both Paxton and Guzman out-fund-raised Bush during the last half of 2021. Guzman led the pack with $3.7 million in contributions, followed by Paxton’s $2.8 million. Bush raised $1.9 million from July through December, while Gohmert brought up the rear with $1 million.

A close inspection of Bush’s most recent campaign finance report shows that the Bush family network is still active. Dozens of donors with business, familial, and political connections to George H. W. Bush, George W. Bush, and Jeb Bush have donated to his campaign. Texas Monthly looked at every donor who gave $5,000 or more in the last half of 2021. All told, at least 62 individuals and entities who either previously served in a Bush administration, donated to a Bush campaign in the past, or have direct business ties to the family provided at least 43 percent of P.’s funding from July through December.

The preponderance of former ambassadors, consiglieri, and Bush 43 administration officials gives the report the feel of a stroll down memory lane. The legacy donors include folks like Ray Hunt, the Dallas oilman who was a major backer of George H. W., George W., and Jeb Bush. Hunt gave $50,000 to the P. campaign. Jeb’s network is in the mix too. Florida developer Sergio Pino, a longtime family friend and major Jeb and George W. contributor, donated $10,000. So did Rio Grande E&P LLC, a private oil exploration and drilling company active in South Texas, which was founded in part by Jeb Bush and his son Jeb Bush Jr. James Baker III, now 91 and still active in Houston civic life, kicked in $2,000. Uncle Marvin Bush? $5,000.

Mark P. Jones, a Texas politics expert at Rice University, said the relatively small donations suggest family loyalty more than deep interest in P. “When I look at George P.’s donations, I see, effectively, respect for the Bush family,” he said. “They’re not giving money to George P. Bush. They’re giving money to George H. W. Bush’s and Barbara Bush’s grandson.”

Meanwhile, many of the biggest business-friendly donors in Texas are ponying up for Guzman. Her top donor by far is Texans for Lawsuit Reform PAC, a nearly $18 million slush fund capitalized by millionaires and billionaires with stakes in construction, finance, oil and gas, real estate, and other industries. TLR previously bankrolled Paxton but had tossed $600,000 to Guzman as of the last reporting cycle. Richard Weekley, the Houston homebuilder and cofounder of TLR, chipped in $500,000. His brother David contributed $50,000. Dallas billionaire Robert Rowling invested a cool $500,000.

Jones has a theory as to why Texas business interests, a conservative but pragmatic bunch, are backing Guzman instead of Bush. “Many of them have not been impressed with his tenure as land commissioner, and I think they also believe the Bush name is far too much of a liability in the Republican primary.” The thinking, Jones said, is that “while he may be able to do well, he isn’t going to be able to win a runoff against Ken Paxton.”

In a January poll of the race that Jones helped conduct, 37 percent of GOP voters said they would never vote for Bush. Only 11 percent said the same of Paxton. But Bush has consistently polled in second place, behind Paxton. And his supporters talk up his extensive outreach in the conservative Hispanic community. Hidalgo County chair Adrienne Peña-Garza credited P. with helping to build the Republican party in the heavily Hispanic Rio Grande Valley long before Trump made head-turning gains in 2020. “It was hard for me to not support someone who has supported us so much,” Peña-Garza said. “George P. Bush has consistently invested in our community and our candidates. He doesn’t just show up for election time. His concern here for the red wave is apparent.”

So far, George P. Bush has won every race he’s run—the two campaigns for land commissioner. In fact, he’s the only one in his family to have won his first bid for office. For the next few weeks, P. will be doing everything he can to ensure he’s not the first to come up short for the second office he’s tried to win.

No comments:

Post a Comment