On the western border of the Greater Kruger Conservancy, where the fence has fallen into serious disrepair, a community of 26,000 people faces an eviction order from the national government. Why do the authorities want them off the land? The answer to this question takes us into an apparent scam run by hunting outfitters, provincial officials and a traditional chief. It also takes us into the desperation and poverty that drives the bushmeat trade.

Listen to this article

Fence, noun: “A barrier, railing, or other upright structure, typically of wood or wire, enclosing an area of ground to prevent or control access or escape.”

WARNING: Graphic images below may disturb sensitive readers.

The Oxford English Dictionary is pretty clear on this point: in order to qualify as a fence, there are certain qualities that a structure is obliged to demonstrate. They are obvious qualities, transparent and uncomplicated, which any school child would accept as self-evident. And yet on a Thursday morning in early October 2021, on a drive through the protected Limpopo bushveld somewhere north of Phalaborwa, Daily Maverick was confronted with a structure that met none of the OED’s standards.

There was a barrier, sure, but in many places it wasn’t upright. In those places where it was upright, there were holes in the wire mesh of various shapes and sizes. Also, given that this was supposed to be an electrified fence, a structure the sole purpose of which was to “prevent or control” the escape of wild and dangerous animals, the area that it enclosed was doubly exposed to breach. The electric current had long ago been deactivated, the wire conductors stolen by poachers and turned into snares.

“To remind you,” said Daily Maverick‘s source, “this is effectively the border of the Kruger National Park.”

See video here.

It was an easy fact for the mind to forget, particularly in light of the sign that appeared at the entrance to the gravel track: “Mthimkhulu Private Game Reserve, no entry without prior arrangement.”

As Daily Maverick was just beginning to learn, the Mthimkhulu traditional community, comprising around 26,000 residents of the twin settlements of Mbaula and Phalaubeni on the banks of the Letaba River, had a long and complex relationship with its namesake reserve. According to the latest interpretation, the land did not belong to them, but to the South African government, which had incorporated it in 1985 into the Letaba Ranch Nature Reserve. The original interpretation, which appeared to fit with post-apartheid land rights legislation — specifically, section 25(7) of the South African Constitution and the Interim Protection of Informal Land Rights Act (IPILRA) — contended that the government was holding the land in trust on behalf of the community.

In the weeks ahead, working off the responding affidavits that had resulted from the government’s attempt to evict the community from the land, Daily Maverick would arrive at a more nuanced understanding of Mthimkhulu history. For the moment, however, it was all about the fact that the Kruger National Park appeared to be missing at least 27 kilometres of fence.

The problem, which now had implications that extended from poaching and illegal trophy hunting to human-wildlife conflict and the ever-present likelihood of a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak, had properly begun back in 2002, when the management of Kruger National Park decided to drop its boundary with Letaba Ranch and incorporate the latter into the Greater Kruger conservancy. At the time, it seemed like an inspired idea — not only would it lessen the pressure on the Kruger’s vegetation, it would enable the wildlife to roam according to historical migration patterns.

And yet by the accounts of community members, the villagers of Mbaula and Phalaubeni had been told nothing of the Kruger’s plans. Daily Maverick was informed that the agreement to drop the fence was concluded between SANParks, the Limpopo provincial government’s department of economic development, environment and tourism (LEDET) and a traditional chief by the name of Pheni Cyprian Ngove, who lived more than 50km away and was not recognised by the locals as their rightful leader.

According to Daily Maverick’s sources, there had been no interaction with the Mthimkhulu community as required by the tenets of IPILRA — no engagement, no signed resolutions and therefore no “prior and informed consent”. One day, we were told, the residents of Mbaula and Phalaubeni woke up to find that they lived a stone’s throw away from the Greater Kruger Park.

As long as the fence was properly maintained, this legislative breach didn’t seem to affect the lives of the community members. But in around 2015, when LEDET and the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries began to neglect their maintenance duties, the effects of the unlawful shortcuts became increasingly evident on the ground.

There were three examples of the fallout that Daily Maverick encountered during our visit to the region. The first was the buffalo spoor that our source pointed out on the gravel track, which ran along the perimeter of the fence on the human settlement side. The spoor, given that buffalo are the primary carriers of the foot-and-mouth virus in African savanna ecosystems, sat there like a wailing alarm — not only could an outbreak destroy the community’s cattle herds, it could also potentially spread through the province, shutting down South Africa’s cattle exports and causing untold economic loss.

The second was a story that had just been published in the Far North Bulletin, under the header, “Is it a free for all on elephant bulls?” The elephants, it appeared, had all escaped from the Kruger, following the scent of Maroela fruit. Seven bulls had been shot dead by LEDET rangers in the streets and exurbs of Phalaborwa, sparking the outrage of the same locals that the rangers claimed to be protecting. For the nearby residents of Mbaula and Phalaubeni, we were told, such encounters were a regular occurrence, although their unwanted visitors, which included hippos, buffalo and the odd predatory cat, were far less likely to be taken down by a LEDET bullet.

Then there was the third example of the fallout, which was perhaps the most devastating. On his phone, Daily Maverick’s primary source — who could not be named due to the threat to his personal safety — held a collection of photographs that illustrated the local trade in bushmeat: a severed baby elephant’s head; a baby hippo strangled by a snare; a range of small animals trapped in excruciating death-poses in the holes of the Greater Kruger fence.

Like the buffalo spoor and the escaped wildlife, the tragedy inherent in the bushmeat trade was that it seemed on the surface to be a direct result of the authorities’ refusal to maintain the fence. Below the surface, however, lay a thread of evidence and testimony that suggested a much darker genesis to the photographs on our source’s phone. The thread had everything to do with the land rights of the Mthimkhulu community and the fact that, up until 2015, the residents of Mbaula and Phalaubeni had been nowhere near desperate enough to poach the Kruger’s animals.

Why? Because up until that fateful year, the community was earning a steady income from lawful and sanctioned trophy hunting.

II.

“We started hunting a long time ago,” Kotlani Elvis Mavunda told Daily Maverick. “The outfitters were putting money into our trust account and we were using that money to uplift the community. We built a crèche and drilled a lot of boreholes. We were also donating to the drop-in centres. That was up until 2015, when the benefits were stopped by LEDET and given to the Mabunda Traditional Authority.”

Although Mavunda held the surname that aligned most closely with the traditional authority, he added, the signature on the 2015 agreement with LEDET had been that of Pheni Cyprian Ngove.

“An official from the government wrote a letter to us saying that anything we do we have to consult Ngove, because in writing it says that he is the chief of Mthimkhulu. It just happened like that one day, although all along the hunting rights had been given to us. We don’t know what changed.”

As Daily Maverick would establish, while there had been a bitter and ongoing traditional leadership dispute between Mavunda and Ngove, the former had for years been recognised by the residents of Mbaula and Phalaubeni as their de facto chief. In providing us with a background to the dispute, it turned out that Mavunda was echoing the heavily referenced and footnoted work of Professor CC Boonzaaier of the University of South Africa, who had recently compiled a history of the Mthimkhulu community.

In brief, from their origins in Mozambique, the Mavunda and Mthimkhulu clans had been closely interlinked, although in 1839 they had settled in the territory of Modjadji the Rain Queen as distinct entities. As refugees, they had no official status; their internal succession battles and the various relocations that ensued were of little significance to the court of Modjadji and their primary allegiances would therefore remain to the original clans.

Then in 1967, when the apartheid government enforced a further relocation of the Mthimkhulu clan to the settlement of Mbaula in the homeland of Gazankulu, it just so happened that they were “arbitrarily” placed under the jurisdiction of the Mabunda Tribal Authority and Chief Ngove. As Boonzaaier made clear, while the headman of the Mthimkhulu clan retained his status, he was appointed as a councillor to the tribal authority “without his consent and against his will”.

Boonzaaier also noted that two regents in succession had pledged allegiance to Ngove “without the consent of the Mthimkhulu Royal Family”, which he interpreted as “untenable” in terms of indigenous constitutional law — this one legal fact, he added, “does not justify [Kotlani Elvis Mavunda’s] deprivation of the chieftainship”. He further noted that “the Mthimkhulu community does not want to be governed by the Mavunda of Ngove” and that should Kotlani Mavunda of the Mthimkhulu not be legally elevated to the position of chief, it would be “difficult to imagine how sound administration and peace will be maintained in the area concerned”.

And yet these last few points, as persuasive as they were, did not feature in the responding affidavit that Mavunda’s advocates would submit to the Polokwane High Court in February 2021. As above, this specific case was all about the government’s attempt to evict the Mthimkhulu community from their namesake 9,000-hectare nature reserve, with the applicants listed as the national minister of the Department of Agriculture, Rural Development and Land Reform (DARDLR), the MEC of LEDET and the Mabunda Traditional Authority.

What did feature in the affidavit were the community’s origins and the fact that for the first 18 years following their enforced relocation to Mbaula, as testified by community elders, they had used the 9,000ha plot as grazing land. In terms of IPILRA and the South African Constitution, the affidavit stated, the law was clear — the Mthimkhulu community were the “beneficial occupants” of the nature reserve as defined by the system of redress that had been instituted by the post-apartheid state to accord communal land rights to former residents of the Bantustans. In this context, the subject of Mavunda’s elevation to chief had “nothing to do with” the relief sought by the community at large.

From the beginning of Mavunda’s responding affidavit, the tone was harsh. After referring to documents in the annexures that demonstrated, uncontestably, how previous government officials had acknowledged the community’s land rights — and how Mavunda had been approached to secure community resolutions for hunting rights “as late as 2013” — it was asserted that the current government, instead of fulfilling its constitutional duties, had “adopted an adversarial position akin to a litigant in a commercial matter”.

The post-apartheid state, Mavunda testified, seemed “hell-bent” on protecting the “arbitrary decisions” of the former Bantu Native Affairs Commissioner, who, “when he was devising means of controlling the natives,” decided “by a stroke of a pen” that the Mthimkhulu community would fall under the ambit of the Mabunda Traditional Authority.

By Daily Maverick’s reckoning, based on the legislation and the documentary evidence, the claim of the Mthimkhulu community to the land was watertight. Also, it appeared that the community qualified for security of land tenure in terms of the Upgrading of Land Tenure Rights Act, a legal course that they had been pursuing. The issue, it seemed, was who benefited from the hunting rights. “The purpose of the eviction application,” Mavunda’s affidavit stated, “[is to] ensure that all benefits relating to the property accrue to [the Mabunda Traditional Authority].”

As for LEDET, Mavunda denied that the provincial department was responsible for the conservation and tourism management of the game reserve. In challenging the eviction order, Mavunda noted that the co-management agreement that had been concluded in 2015 between LEDET and the Mabunda Traditional Authority was unlawful — for the simple reason that the Mthimkhulu community had not been consulted. On this point, section 2(1) of IPILRA was about as unambiguous as it’s possible to get: “no person may be deprived of any informal right to land without his or her consent”.

And it was this issue of consent that Mavunda kept returning to in his interview with Daily Maverick.

“If Ngove came here looking for a community resolution for hunting rights,” he told us, “nobody would recognise him. They don’t know what he looks like.”

III.

The hunting fraternity in South Africa, as Daily Maverick discovered during the course of this investigation, is governed by a set of laws and regulations that are designed to ensure two outcomes: first, all proceeds must flow to the rightful beneficiaries; second, animal populations in a given area must remain healthy and sustainable. But in the document entitled “Allocation of Game Quota to a Traditional Authority for 2021/2022 Financial Year,” signed by LEDET’s deputy director-general of environment and tourism on 23 March 2021, it was apparent that both of these outcomes had been compromised.

For starters, unlike the previous year, the hunting quotas for the Letaba Ranch Nature Reserve had been issued jointly to the Mabunda Traditional Authority and the Majeje Traditional Authority, which had been facilitating the process on behalf of the indigenous community to the north. In other words, where LEDET’s assigned hunting quotas for the 2020/2021 financial year had specified how the game was to be divided — for instance, seven buffalo for Mabunda, seven for Majeje and 13 for “the state” — in the latest iteration there was no such breakdown.

Then there was the fact that the numbers themselves had jumped at an alarming rate, particularly as far as the most lucrative animal was concerned: for the 2020/2021 financial year, LEDET had assigned a total of 11 elephant for “reduction”; now, in 2021/2022, there were all of a sudden 23 elephant up for grabs.

On a Thursday afternoon in Pretoria in early November 2021, Daily Maverick met the owners of two commercial hunting operations who, due to the above anomalies, were facing an impossible situation. While neither of the men consented to be named, citing the potential damage to their reputations in the eyes of their international clientele, they were more than willing to guide us through the paper trail.

The first man, who for the sake of clarity we’ll call “Malan,” had secured the exclusive hunting rights for the Majeje Traditional Authority’s quota, made up (based on the split) of 15 buffalo and 12 elephant. The second man, who we’ll call “Swanepoel,” had secured the rights for the Mabunda Traditional Authority’s quota, made up of 15 buffalo and 11 elephant.

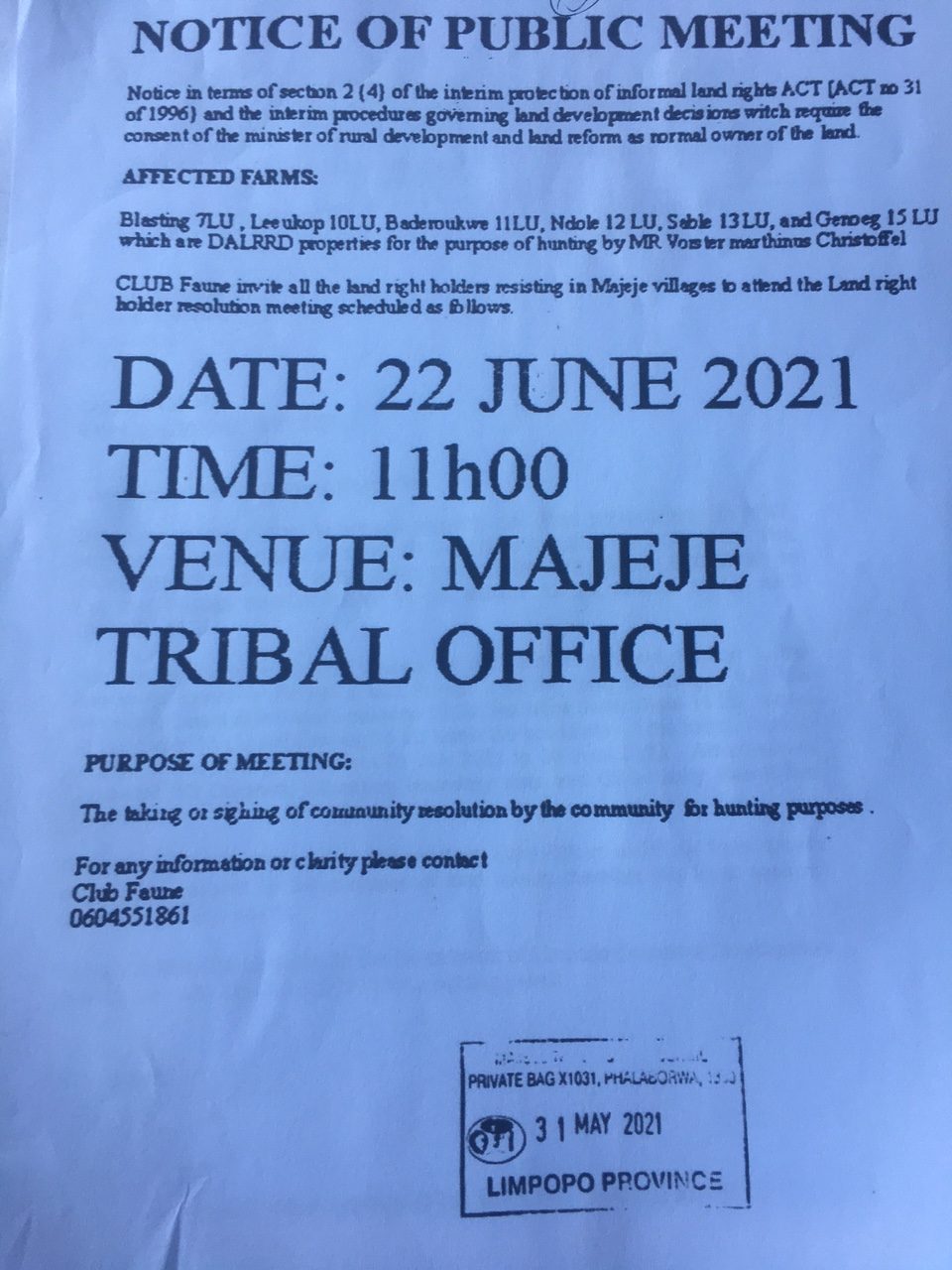

Malan took us through the paperwork to demonstrate that, for him at least, everything was legitimate. After LEDET’s initial quotas, he explained, the next step was allocation of the hunting rights. Here, DARDLR had assigned the rights from 1 July 2021 until 30 June 2022 to one “Christoffel Marthinus Vorster,” a Phalaborwa-based hunting outfitter and middleman from whom Malan — like Swanepoel on the Mabunda portion of the quota — had then bought them. As the third step in the process, Malan handed us a copy of the “Notice of Public Meeting” that had been advertised by Vorster for 22 June 2021 in the “Majeje Tribal Office”. This was the all-important “taking or signing of community resolution… for hunting purposes” as required by section 2(4) of IPILRA.

Finally, as the fourth step in the process, LEDET had entered the picture again with the allocation of hunting permits. The farms on which Malan had been authorised to hunt were the same farms that belonged to the Majeje community, a fact he knew from prior experience. But for Swanepoel, who was new to the region, there was a problem. On his own hunting permits, which were shared with Daily Maverick, he had been allocated the same Majeje farms.

“We actually passed each other out in the veld,” Malan told us. “We smiled and waved, but neither of us knew what the other was doing there. Later, when we started talking, we realised that something was very wrong.”

The kicker for Swanepoel, he explained, was when he realised that he could not secure the proper signatures for export of the “hunting trophies” to his international clients. Eventually, this resulted in Swanepoel withholding R677,000 in payments to one “Chris van der Westhuizen” of African Pride Hunting Safaris. As it turned out, there had been three middlemen involved in the on-sale of the quotas to Malan and Swanepoel — Vorster, who had originally been assigned the joint rights by DARDLR, his partner Victor Britz and Van der Westhuizen.

Given the amount of money involved, it wasn’t long before the lawyers’ letters started flying. In a letter dated 19 October 2021, addressed from Van der Westhuizen’s attorneys to Swanepoel, it was noted that the agreement to purchase the hunting quota of the Mabunda Traditional Authority had been concluded at R150,000 per buffalo and R460,000 per elephant.

“We have been informed that during September 2021 you conducted guided hunts for clients for the hunting of 13 buffalo and two elephant,” the letter stated, “through our client acting as agent and intermediary in order to facilitate your hunting activities in respect of the quota allocated to the Mabunda Tribal [sic] Authority at Letaba Ranch (allocated solely and exclusively to our client by agreement between our client and Mr Chris Vorster and Mr Victor Britz).”

Translated, this meant that Swanepoel owed Van der Westhuizen a total of R2.87-million for the September hunt. The attorneys noted that Swanepoel had paid the majority of the amount, but that he “refused to pay the balance of R1.2-million to [Van der Westhuizen] due to undue influence and interference by a third party, [Malan]”.

On 21 September, the letter continued, Swanepoel agreed to pay the outstanding R1.2-million subject to a number of conditions, including that “all transport permits” for the skins, tusks, tails, ears, buffalo skulls, capes and shoulder mounts were arranged.

“You subsequently and during late September 2021 made payment of R543,000 directly to Chris Vorster for the outstanding amount owing to the Mabunda Traditional Authority but have failed and/or refused to make payment of the balance of R677,000 due, owing and payable to our client, despite demand.”

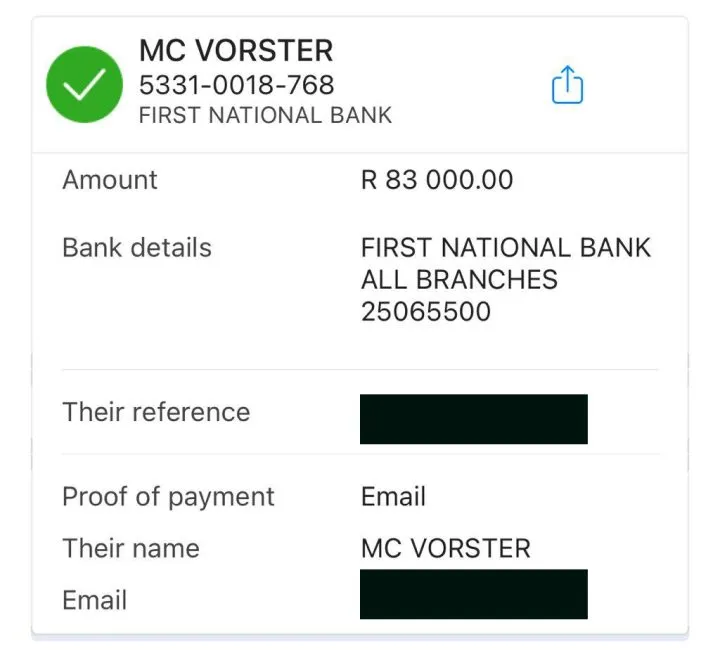

At the venue in Pretoria in early November, Swanepoel handed over evidence of the payments that had been made, including the R543,000 directly to Vorster.

“I want to know where the money has gone,” he told Daily Maverick. “I paid R2.2-million to two people in eight days, and that’s a helluva lot. Where is it?”

IV.

The obfuscations and evasions that we met in our attempts to get answers to this question were spellbinding in their creativity. Max-Wilhelm Rossle, an associate at Peter Le Mottee attorneys, sent a 1,100-word response on behalf of Van der Westhuizen in which he repeated different versions of the following sentence: “All quotas allocated at Letaba Ranch and all hunting rights held by Mr Chris Vorster are, in the absence of material evidence to the contrary or a formal finding to the contrary by a competent Court, accepted by my client to be bona fide and prima facie legitimate and lawful until proven otherwise or overturned by a competent Court of Law.”

At the beginning of the missive, however, despite the fact that Rossle had acknowledged in his letters to Swanepoel the above mentioned R543,000 payment “directly to Vorster” — a payment that had clearly been accepted by Van der Westhuizen too — he’d stated that Daily Maverick “should in no way attempt to… link the commercial affairs of [his client] to those of Club Fauna France and its role-players”.

Accordingly, when it came to distribution of the funds and the pivotal issue of the Mthimkhulu community’s share, Rossle suggested that Vorster and Britz were the only ones with the answers.

As with Van der Westhuizen, we had only two questions for Vorster and Britz of Club Fauna France. First, did the company, acting on behalf of Chief Ngove and the Mabunda Traditional Authority, obtain a resolution from the Mthimkhulu community for the 2021/2022 hunting quotas? Second, what portion of the R2.2-million paid by Swanepoel to Van der Westhuizen and Vorster had been distributed to the community?

In the 24-hour period after the questions were sent, Vorster — whose son Marthinus Vorster had been sentenced to five years in prison for “anti-black terrorist activities” and the desecration of an ANC politician’s grave (upon arrest in 2010, the police had confiscated “pipe bombs, semi-automatic guns and ammunition”) — sent a series of emails to Daily Maverick requesting a face-to-face meeting.

We had our facts “completely wrong,” he stated, and he would make himself available to personally hand us the “documentation” and set the record straight. In the end, despite repeated requests, Vorster did not send us the alleged documentation. Neither did he provide substantive answers to our questions.

As for Chief Ngove, whose name was listed on LEDET’s 2021/2022 quotas, our questions were basically the same: was there a community resolution and to whom had the hunting proceeds been distributed? But the second question, this time, had a much broader scope.

“Daily Maverick has noted,” we began, “that the Mabunda Traditional Authority has not been registered in terms of the Communal Property Associations Act of 1996. Given this apparent fact, to whom have the hunting proceeds been distributed since 2015, when the co-management agreement for the Mthimkhulu Game Reserve was signed between the Mabunda TA and LEDET?”

Chief Ngove’s response was as dismissive as it was brief:

“I have been advised by our attorney that it is not advisable to comment on a live court matter. Regrettable that I cannot be of assistance at this stage.”

Then there was LEDET, which opened by taking the same line as Ngove. We wanted to know, since the communal land rights of the Mthimkhulu community had been recognised by previous government officials (including the former DG of DARDLR), which legal precedents had motivated the eviction order. In other words, why did the tenets of IPILRA no longer apply? We were told, as if this was somehow new information, that the matter was before the Polokwane High Court.

Okay, but did the Mthimkhulu community give their free, prior and informed consent to the 2015 co-management agreement between LEDET and the Mabunda Traditional Authority, as required by the tenets of IPILRA?

The non-answer read as follows: “LEDET has signed a co-management agreement with the Mabunda Traditional Council (Ngove) in which the Mthimkhulu Community form part of the larger community structure under the tribe.”

Can LEDET then prove that the Mthimkhulu community has been receiving benefits from hunting since 2015?

Again, the same nonsensical non-answer, with a brazenly absurd twist at the end for effect: “LEDET has signed a co-management agreement with the Mabunda Traditional Council (Ngove) in which the Mthimkhulu Community form part of the larger community structure under the tribe and all benefits accrued to the tribe are for the benefit of the communities under the tribe.”

This was about as direct an admission as Daily Maverick was likely to get: if LEDET, as the “competent authority” in charge of the hunting quotas and the permits, had proof that the Mthimkhulu community were receiving their rightful benefits, we can only assume that the department would have shared it with us.

As for the absent community resolution for the Mabunda portion of the 2021/2022 hunting quotas, LEDET referred us to DARDLR, with which “the IPILRA mandate lies”.

At the time of this writing, Minister Thoko Didiza’s office had yet to reply to our questions.

V.

If it’s to be placed anywhere, this investigation must be placed within the context of the UN Convention on Biological Diversity’s “New Global Framework for Managing Nature through 2030”. Drafted in Montreal in July 2021, the framework, which ultimately seeks the ratification of 196 member countries, includes 21 “targets” for the end of the decade.

The first of these targets reads as follows:

“At least 30% of land and sea areas global (especially areas of particular importance for biodiversity and its contributions to people) conserved through effective, equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas (and other effective area-based conservation measures).”

The science on which this target is based is inarguable. In May 2019, working off the contributions of 145 “expert authors” from 50 countries — plus the inputs of another 310 “contributing authors” — the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) released a report that environmentalist George Monbiot called “the biggest and worst news humanity has ever received.”

At the time of the report’s release, IPBES chair Sir Robert Watson had these words for the world’s press: “The overwhelming evidence of the IPBES Global Assessment, from a wide range of different fields of knowledge, presents an ominous picture. The health of ecosystems on which we and all other species depend is deteriorating more rapidly than ever. We are eroding the very foundations of our economies, livelihoods, food security, health and quality of life worldwide.”

And so, given that the first measure for the amelioration of these effects is protection of 30% of the planet’s surface — with “conservation corridors” listed as a primary method — it’s hardly a stretch to argue that South Africa’s Greater Kruger conservancy is a major player in humanity’s fate.

Which begs the question: do the 21,200 square kilometres that make up the KNP and Greater Kruger — an area of protected land as large as Belgium — serve as an example of an “effective, equitably managed, ecologically representative and well-connected” conservation corridor?

To the first pair of criteria, if the story of the Mthimkhulu community is any indication, the answer is obviously “no”. By definition, an effective and equitably managed corridor cannot sustain a system of entrenched corruption that robs 26,000 human beings of their collective income.

Neither can it sustain the trade in bushmeat — the snares in the village square; carts transporting elephant limbs — that is a direct result of the hunger and desperation caused by such corruption.

Also, if a corridor is to be “well-connected,” the boundary fence that separates it from the outside world cannot, by implication, be porous. Human-wildlife conflict must be kept to a minimum and the threat of a viral outbreak, like foot-and-mouth disease, must be strictly and properly managed.

We are therefore left with only the third criterion, “ecological representation,” on which KNP and the Greater Kruger can score some positive marks. But here, although the reserve’s biodiversity is healthy and intact, the illegal hunting of keystone species is another problem over which SANParks has no apparent control.

“The management of community land adjoining Kruger National Park remains a complex issue,” stated Luthando Dziba, the acting CEO of SANParks, when Daily Maverick put these issues to him. “SANParks developed the Greater Limpopo Transfrontier Conservation Area (GLTFCA) Cooperative Agreement framework in 2018 in order to ensure there are shared principles about cooperation for conservation and development in the Greater Kruger and the Greater Limpopo TFCA. There are however conservation areas that fall outside the mandate of SANParks and these include the Mthimkhulu Private Game Reserve and the Letaba Ranch, which are under the management authority of LEDET.”

Dziba hoped, he told Daily Maverick, that SANParks did not “appear evasive”. But on this story, as he must have known, evasion was the central theme. DM/OBP

No comments:

Post a Comment