A shoot-out at a Big Bend ranch captured the nation’s attention: first as an alleged ambush by undocumented migrants, then as a fear-mongering hoax. The real story is much more mysterious.

Walker Daugherty was lying in bed when he jolted awake, suddenly alert. He shook his fiancée, Ashley Boggs, to rouse her. “I heard voices outside,” he said. “I need to check it out.”

It was about 9:30 p.m. on January 6, 2017, at the Circle Dug Ranch, a 15,000-acre desert spread in the Big Bend, about two hundred miles southeast of El Paso. Inside the ranch house, a humble rock homestead built on the side of a barren hill, it was quiet.

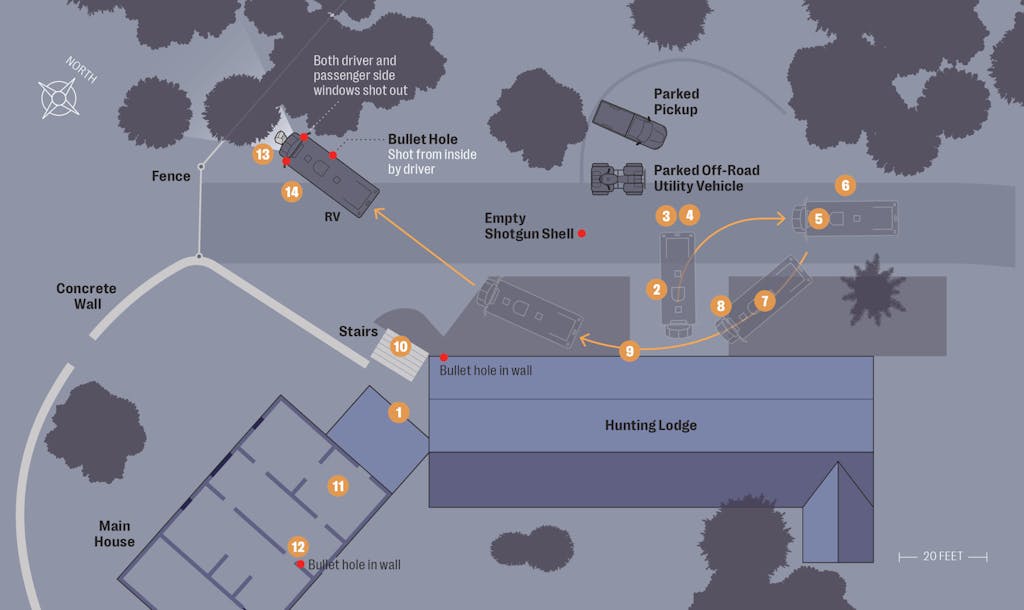

Walker, 26, was working as a guide for his family’s hunting business, now called Big Rim Outfitters, along with Morgan and Michael Bryant, his younger sister and her husband, who were asleep in a separate room. Their two clients that week—a chiropractor and a registered nurse from Pensacola, Edwin and Carol Roberts—had retired for the evening to their RV, a rental with splashes of desert scenery on its white exterior, which they’d parked in front of a hunting lodge with a dining hall and bedrooms, about fifty feet east of the main house. Edwin and Carol were sharing the camper with their Jack Russell terrier, Tinker Bell, and a talking African gray parrot.

Walker, who is a lanky six foot three, reached next to his nightstand for his loaded double-barrel shotgun, a Remington 12-gauge, and walked to the front of the house. He cracked open the door to the porch, where a single light illuminated a set of steps dropping six feet to a dirt-and-gravel yard. He stood there for a moment in his boxer shorts, listening in the dark. Then he heard the screams.

Ashley, 27, called out from the bedroom, telling Walker to wait for her, but he’d already run into the darkness. She was loading her pistol when she heard him outside, yelling at someone, “Hey, what are you guys doing?” She raced to alert Morgan and Michael.

In the days to come, the story of the “border ambush” that followed would reverberate outward from the Circle Dug, taken up by blogs and national media, then by politicians and late-night talk show hosts, all certain that they knew the real story of what happened that night.

Even before he heard the voices outside, Walker had been on edge. The ranch is isolated, lying just five miles east of the Rio Grande. It’s a stark moonscape of windswept hoodoos and valleys of lava rock all bounded by the dramatic rim of the Sierra Vieja, one of the state’s most remote mountain ranges. The nearest stretch of paved road, FM 170, peters out in Candelaria, a flyspeck border village more than seven miles to the south.

The Circle Dug had been burglarized less than three weeks earlier: someone had taken hunting knives, a flashlight, frozen pizzas, soft drinks, camouflage hunting jackets, and a $600 sleeping bag. The day after the burglary, Morgan was surveying the ranch’s bleak hills from the roof of the house when she looked through her spotting scope to the east and saw a group of people hiking up the Sierra Vieja.

The Circle Dug is positioned in a corridor frequently used by both drug smugglers and undocumented migrants. Hunters at the ranch frequently come across empty water bottles and old sleeping bags left in shallow caves where people seek shelter before their climb up the Sierra Vieja near Capote Falls, the tallest waterfall in the state, which spills over the mountain rim and plummets 175 feet to the desert floor. From the top of the Sierra Vieja, a twenty-mile hike leads to a lonely stretch of U.S. 90 between Marfa and Valentine, where migrants are picked up by smugglers.

Morgan called Border Patrol to report the burglary, and agents apprehended the group of migrants she’d spotted on the Sierra Vieja and recovered some of the stolen property. According to a Border Patrol report, a member of the family said they were being “overrun” by migrants: in December 2016, several groups had come to the ranch house to ask for water and other assistance.

When Edwin and Carol arrived at the Circle Dug for their week-long hunting excursion a few weeks later, Walker told them about the break-in and asked if they planned to arm themselves in their RV. Edwin, a heavyset former college football player, replied that he had a .357 Magnum revolver. “Okay, just keep it close to your bed,” Walker said, as Edwin would later recall. (Through their attorney, he and Carol declined a request for an interview.)

On the first day of the couple’s hunting trip, Carol shot an aoudad, a species of wild sheep with curved horns and a long beard that originated in the mountains of Northern Africa and has become invasive in the Big Bend. The next day—January 6—the hunters came up empty-handed. They returned home at four in the afternoon, enjoyed a dinner of ribeyes, shrimp, and potatoes, and called it an early night. Edwin had a small cocktail, and Carol had a glass of wine. Contrary to later speculation, no one in the camp was drunk. The couple, then both in their late fifties, watched part of a movie in their RV and went to bed.

They were nodding off when they were awakened by a frightening noise. The locked side door of the RV was rattling loudly. It sounded as if someone wanted in. Tinker Bell barked. Edwin jumped out of bed and grabbed his gun. “Who is it?” he later recalled asking. “Hey! I got a gun in here. Go away.”

The door handle shook again. He heard a man’s voice outside the RV: “All we want is the motor home.” The demand, he noted, was delivered in clear, unaccented English. Tinker Bell was growling loudly in Carol’s arms, and she didn’t hear the voice. But to Edwin, the man sounded sinister, terrible. “It was just like the devil was on the other side of that door,” he said later. Then he heard the door rattling again. He shot a single round through it.

Back at the ranch house, Ashley bolted out onto the porch and down the stairs. She saw Walker hiding behind Edwin and Carol’s RV but didn’t see anyone else. “Where are they?” she asked.

“Go back inside now!” Walker shouted. “They have guns!” Walker had been standing only ten or fifteen feet from the RV door when Edwin shot it. Walker assumed an unknown assailant, not Edwin, was doing the shooting.

Meanwhile, Morgan and Michael were getting dressed as quickly as they could. Morgan, 24, grabbed her revolver. Like Ashley, she was packing a .38 Special. Michael, 32, sturdily built and balding on top, got his Bushmaster AR-15, a semiautomatic rifle.

They hurried to the front porch, where they heard Edwin and Carol screaming and the RV’s horn honking. Michael ran down the steps. He saw Walker behind the vehicle, barefoot and in his boxer shorts. Morgan stayed on the porch as Michael darted for cover behind an off-road utility vehicle. Then he ran to join Walker.

Michael had not heard Edwin’s round go off, but he immediately sensed that Walker was “super hyped up.” Walker told him that he’d been shot at. Edwin and Carol, he said, were being held hostage in the RV. “How are we going to get them out?” Michael asked. Michael thought he heard another gunshot. The reverse lights flashed on, and the engine revved: Edwin had moved to the driver’s seat. Suddenly, the motor home was backing up. “They’re trying to steal the RV,” Walker said. The question of why a hijacker would blare the horn while absconding in a stolen vehicle did not cross Walker’s mind. He was preoccupied with protecting his clients from an apparent kidnapping. “Shoot the tires!” he said.

Walker fired first, deflating the rear passenger-side tire. Michael shot twice at the front tire on the same side. The RV lurched forward. “Take out the driver!” Walker yelled. His view through the front windows was obscured by curtains; he ran alongside the vehicle, then pressed his shotgun to the passenger window and blasted through it and the curtains. Michael fired twice into the cab. Then he backed up to a tree and waited for someone—anyone—to emerge from the RV.

In the tense moments after Edwin had shot a hole in the door of the RV, Carol had peeked through the back window, where she saw the barrels of two guns behind the motor home. Those barrels belonged to Walker’s shotgun and Michael’s rifle, but Edwin and Carol didn’t know that.

Edwin told Carol to “dump” to the floor. He threw the RV in reverse, aiming to run over the armed men lurking behind them. Then he put the RV in drive. Edwin was hastily steering the RV toward the house, still honking the horn and hollering to get the attention of their hunting guides—his allies, he called them. That’s when Walker shot through the passenger window, peppering Edwin’s right arm with buckshot. The passenger and driver’s side windows both shattered, pelting Edwin with glass. His ears rang; his arm was bloody and numb. Blood spattered the steering wheel, windshield, and ceiling and even dripped down the outside of the driver’s side door. Veering out of control, the RV crashed into a cedar post holding up the roof of the hunting lodge, then sideswiped the retaining wall as it approached the house.

At the house, Morgan had cocked the hammer of her revolver as soon as she heard the hail of gunfire. She was watching from the porch as the RV hit the hunting lodge and rumbled across the yard from east to west. In her recollection, that’s when her brother sprinted toward her. As he lunged up the stairs, he was framed by the glow of the porch light. Then Morgan heard another shot.

A lone bullet struck Walker in his right rib cage. The force rocked him sideways. It felt like a hot, sharp iron poking his side, he would later say. On impact, the bullet flattened into a mushroom shape. It plowed into his abdomen, destroying the upper third of his liver, then tore through his right lung and diaphragm. The bullet didn’t stop until it reached the bottom of his left lung, where it lodged not far from his heart.

Walker took a breath, and blood spurted from the wound. Walker had seen plenty of lung-shot animals during his career, and they didn’t last very long. Assessing his wound, he thought, That’s not going to work.

Morgan helped her brother into the house. He collapsed into a chair in the kitchen, already in shock. Morgan panicked. She needed to put down her .38 pistol, but it was still cocked. Instead of lowering the hammer to disengage it, she pulled the trigger and fired a round that went through her own camouflage backpack and into the wall. She placed the gun on the kitchen table and gathered blankets from a couch, pressing them to Walker’s wound, stanching the blood.

Ashley had been in the house looking for a phone to dial 9-1-1 when Walker and Morgan came through the front door. Only then, Ashley would later tell investigators, did she see Edwin and Carol’s motor home zoom past the front steps. Morgan remembered the timing differently, saying she saw the RV drive by before she saw Walker racing toward her, which places the vehicle in the direction of the unknown shooter. Either way, the RV lumbered about fifty feet past the steps before slamming into a boulder, where it came to a stop.

Ashley finally found her phone and called 9-1-1. Michael, meanwhile, had no idea that Walker had been shot. Still outside, looking for his brother-in-law or any sign of the intruders, he was standing in front of the porch steps when Edwin appeared, seemingly from nowhere. He had bailed out the driver’s side door, leaving Carol in the motor home. “You shot me! You shot me!” Edwin screamed, using his injured right arm to point his .357 Magnum at Michael.

“Drop the gun!” Michael said. “It’s me, Michael!” Edwin lowered the revolver. “I’ve been shot, man,” he said. “I’m bleeding bad.” Michael helped him up to the kitchen. Edwin kept asking after his wife, so Michael went outside to check the RV. He found Carol still on the floor. She’d been screaming for Edwin, and when he didn’t answer, she assumed he was dead.

Michael led Carol to the house, and she and Edwin retreated to a bedroom by themselves, where Carol, who had more than three decades’ experience as an intensive care nurse, applied pressure to Edwin’s wounds. Michael helped Walker to the floor and stayed beside him. Despite their six-year age gap, the men had been close friends long before Michael married Walker’s sister. For a couple of years, the two lived together in a travel trailer while working construction jobs in Austin. Now, as Walker struggled to breathe and coughed up blood, Michael held his finger over a blanket against the hole in Walker’s abdomen and waited for help to arrive.

At 9:50 p.m., an emergency dispatcher for the Presidio County Sheriff’s Office, in Marfa, the county seat, received Ashley’s frantic call. “We’re at the Circle Dug Ranch,” Ashley told the dispatcher, barely maintaining her composure as Morgan screamed in the background. “There’s illegals here, and they’re shooting at us. They shot Walker.”

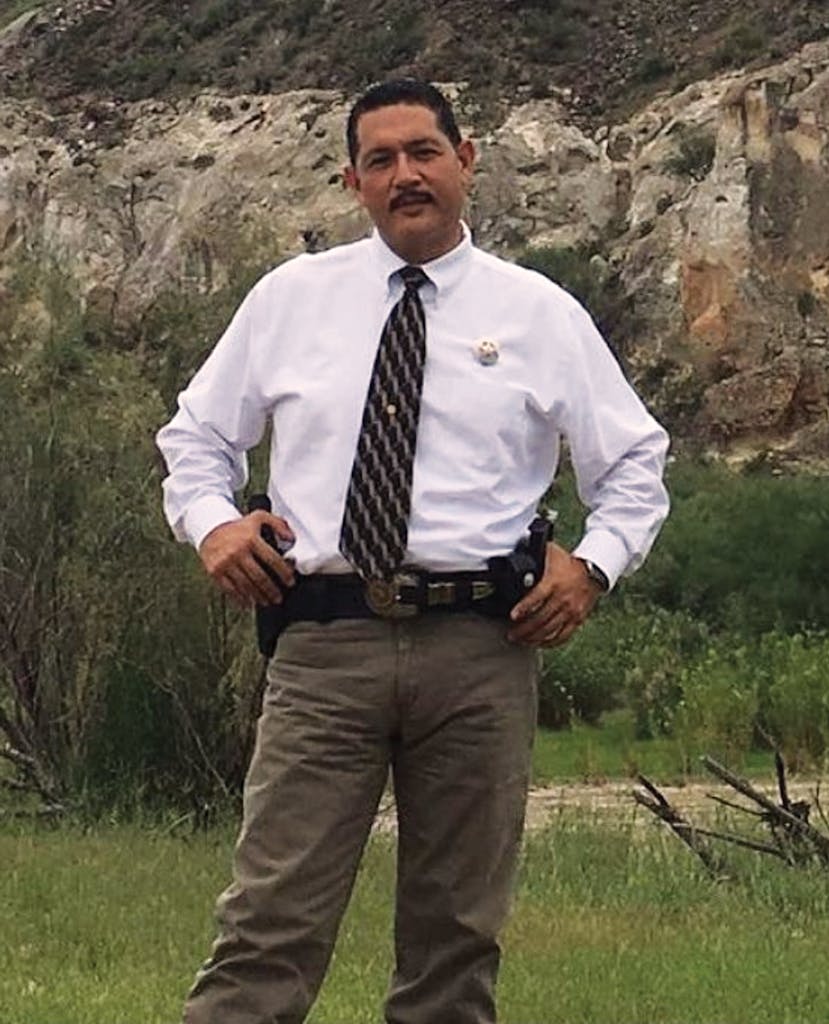

At the time, 41-year-old Joel Nuñez, the chief deputy of the Presidio County Sheriff’s Office, was responding to a medical emergency relatively close to the Circle Dug. Nuñez is a third-generation resident of Presidio, a Rio Grande town of roughly four thousand people sixty miles south of Marfa. He has served as a lawman for more than two decades, and he looks the part: his white shirts are crisp, and his dark, gelled hair is nearly as close-cropped as the goatee he now sports.

That night, an ambulance driver had been unable to find a ranch near the ghost town of Ruidosa, where a teenage girl was suffering from severe abdominal pain, so Nuñez had driven more than an hour northwest from his home to guide the ambulance to the correct residence. Presidio County is the fourth-largest county by landmass in Texas—it’s more than twice the size of Rhode Island—so the half-dozen deputies in the sheriff’s office cover a wide territory.

About sixty yards from the Circle Dug headquarters, the road crests a hill and takes a sharp right, revealing an overlook of the secluded house below. Nuñez stopped there and climbed out of his truck. It was just after 10:30. He paused for a few seconds, watching for trespassers and listening for gunshots, vehicles, noises—anything.

Nuñez regarded Presidio County as a safe and quiet place, and he couldn’t remember the last burglary he’d investigated. (He was unaware of the burglary at the Circle Dug just three weeks earlier.) But the dispatcher had told Nuñez there had been screaming and gunfire on the 9-1-1 call. It occurred to him that he didn’t know what he was walking into, or whether he’d walk out.

As Nuñez stood under the starry night sky, looking down at the ranch house, he heard and saw nothing out of the ordinary. He got back into his truck and drove down the hill, parking close to the house. He jumped out of the vehicle, his semiautomatic rifle drawn, then approached the front door, calling out to identify himself to the hunting party. He entered the kitchen and saw Walker bleeding on the floor. Nuñez asked his dispatcher to send backup from Border Patrol and other nearby law enforcement, as well as a helicopter to evacuate Walker. Then he posted up near the front door, fearing another attack. He waited an interminable forty minutes for the first Border Patrol agents to arrive. One of them, a medic, took over Walker’s treatment and gave him an IV.

At 11:20 p.m., Border Patrol agents led by Silverio Escontrias, the chief patrol agent for Presidio Station, began to walk the perimeter of the house, looking for signs of assailants. They also jagged southward, on the chance that they might catch an intruder fleeing to Mexico. Dozens of agents combed the ranch for vehicles, footprints, spent shell casings, or people hiding in the brush. Then they checked the surrounding ridges and hills. Nothing.

The crime scene was declared secure at a quarter to midnight. The officers had found no footprints that didn’t belong to the hunters themselves, Nuñez would later report. The only bullet holes and spent casings were traced to the hunters’ guns. This doesn’t seem right, Nuñez thought.

Michael walked Nuñez and Escontrias, soon joined by Presidio County sheriff Danny Dominguez, through the scene of the shoot-out. Although he was clearly shaken, Michael had an almost-photographic recall, with each gunshot accounted for. Nuñez exchanged knowing glances with the other lawmen. “Did you hear what he just said?” he quietly asked them afterward. “It seems like they just shot each other.”

At 1:33 a.m., a helicopter flew Walker to the University Medical Center of El Paso. Edwin was driven to a Big Bend–area medical clinic, then flown to the same hospital. Border Patrol agents scoured the area for the rest of the night. At about three in the morning, Nuñez, Morgan, Michael, Carol, and Ashley drove to the sheriff’s office in Presidio, where the hunters wrote down witness statements. Nuñez returned to the Circle Dug after sunrise and continued to search for clues.

Nuñez was sure that Walker had shot Edwin. The question was, who shot Walker? Nuñez suspected that Michael had done it inadvertently. Michael had also fired his semiautomatic rifle into the cab. Both of those shots passed through the passenger and driver’s side windows, possibly grazing Edwin’s arm but leaving not so much as a scratch on the RV itself. Investigators had found one of Michael’s .223-caliber bullets embedded in the concrete plaster of a wall near the steps where Walker was injured. Nuñez wondered whether Michael’s other bullet had struck his brother-in-law as Walker was running up the steps.

To Nuñez, the hunting party seemed like good people. He’d heard them praying throughout the night, and their stories had never wavered under questioning. They adamantly believed they’d been attacked by trespassers, and Nuñez wanted to give them the benefit of the doubt. He just wasn’t convinced that anyone else had been out there.

The Robertses’ RV at the Circle Dug after the shoot-out on the night of January 6, 2017.

Courtesy of the Presidio County Sheriff’s Office

The hunting lodge and main house at the Circle Dug on the morning after the shoot-out.

Courtesy of the Presidio County Sheriff’s Office

For Walker, the night of the shooting was a blur of disconnected moments. He remembered his family praying for him on the kitchen floor of the Circle Dug. He felt calm, believing that God was telling him not to worry, that he would be fine. After that, he remembered pain, the cold, and being loaded onto a stretcher before passing out. He briefly awakened on the helicopter and was jarred by the sight of a masked man, an EMT, looking down at him. Walker was roused again when the chopper thudded to a landing in El Paso. Emergency personnel rushed him inside the hospital, like a scene from a TV drama. “And then I was out,” he would later say. He remained unconscious for several days.

As Walker lay in his hospital bed, news of the alleged ambush spilled from the mountains and badlands of the Big Bend and quickly went viral online. A friend of Ashley’s set up a GoFundMe campaign for Walker, who did not have medical insurance. In just two days, the page generated $18,000 from more than two hundred donors, with the gifts eventually reaching $26,280.

Donald Trump’s inauguration was less than two weeks away. His ultranationalist presidential campaign, in particular his description of Mexican immigrants as “rapists” and “criminals” and his promises to build a wall along the southern border, had polarized the country. Trump supporters leaped on the Big Bend shoot-out story. Facebook posts and various blogs, including Culture Vigilante and Freedom Daily, ran with it, the latter framing the shooting as a vicious attack by an invading “gang of illegals.”

On January 8 agriculture commissioner Sid Miller posted two photos of Walker to his Facebook page. In one, Walker is in camouflage, kneeling and smiling beside a dead African antelope. In the other, he’s slumped in a hospital bed, eyes closed, an intubation tube running down his throat. “Walker is a man of God and is now a hero,” Miller wrote in the post. “This is why we need the wall and to secure our borders. Anyone who says that the people illegally crossing into our country are just those seeking a better future for their families simply do not understand what is happening on our borders. There are violent criminals and members of drug cartels coming in and [we] must put a stop to it before we have many more Walker Daughertys.”

Nuñez was infuriated when he saw the post. He didn’t believe there had been an ambush, and he resented Miller’s attempt to exploit the shooting for a political agenda.

First, Walker had been an avatar for right-leaning nativists. Now the narrative flipped.

He had listened to an interview that a Texas Ranger named Juan Torrez had conducted with Edwin in the hospital shortly after he woke up from surgery on his arm. Edwin told the Ranger about the sinister voice that demanded his RV, a command delivered in unaccented English. In Nuñez’s experience, almost no one in that stretch of the borderland spoke without an accent—certainly not the migrants crossing the desert in the middle of the night. He also wondered why anyone out there would want to take a big RV, anyway. It would have been impossible to drive the motor home up the rough and craggy foot trails to the rim of the Sierra Vieja. And it would be nearly as challenging to sneak the vehicle back to Mexico.

Nuñez was also dubious about the possibility that drug runners had ambushed the hunters. He knew that Mexican cartels hired people to backpack drugs across this far-flung corner of West Texas, but he’d never heard of them shooting at anyone. The last thing smugglers would want is to draw attention to themselves in an area that is already crawling with the law. Indeed, more than three dozen agents and law enforcement officers from a bevy of local, state, and federal outfits had descended on the Circle Dug Ranch to search for the alleged RV bandits that night.

Nuñez still believed that a stray bullet from Michael’s AR-15 had struck Walker. Nevertheless, in the days after the ambush, apprehensive ranchers around the Big Bend called the Presidio County Sheriff’s Office to ask if there was any truth to the unusual allegations. One rancher told Nuñez he was ready to start shooting border crossers on his property. Hoping to calm fears and counter what they considered a false narrative of border violence, Nuñez and county sheriff Dominguez insisted there was no evidence of an attack. On that part of the border, “gun violence just doesn’t happen,” a Border Patrol spokesperson told the Albuquerque Journal.

The sheriff’s office concluded its investigation less than two weeks after the shoot-out, recommending that Michael and Walker be charged with deadly conduct, a third-degree felony, for firing their guns in the direction of other people. The brothers-in-law were indicted on February 15. Presidio County district attorney Sandy Wilson would later tack on a more serious charge for each man: aggravated assault with a deadly weapon, a second-degree felony punishable by as much as twenty years in prison.

Wilson and Nuñez speculated that the voice Edwin had heard outside the RV had been Walker posing as a thief as a prank—a prank that went horribly awry.

First, Walker had been an avatar for right-leaning nativists. Now the narrative flipped, and he found himself on the receiving end of national scorn from liberal detractors of the incoming president. Some speculated that members of the Daughertys’ hunting party had either pulled a blame-the-Mexicans defense to cover up their own drunken rumpus or that they were so riled by Trump’s anti-immigration rhetoric that they got spooked and shot one another in a bumbling exchange of friendly fire. On February 21, Stephen Colbert mocked Walker by name on CBS’s Late Show. “The truth hurts,” Colbert riffed during his opening monologue. “Not as bad as those bullets, but still.”

For the most part, Walker was oblivious to the widespread derision. While he was in the hospital, his family didn’t even mention the criminal allegations, believing his medical condition was too precarious for him to hear the difficult news. Doctors had cut a football-size opening from his sternum to his navel to operate on his liver and other organs, an emergency procedure to stop the internal bleeding. Then there was a second operation, to remove blood clots from his liver. It was too dangerous to remove the bullet, so the doctors left it in his lung, where it was eventually ensconced in tissue. The wounds became infected, and Walker experienced life-threatening sepsis, with fluid draining into bags. He shed forty pounds from his already-lean frame. “He lost so much weight he was skin and bones,” Morgan told me.

When his parents finally did break the news to him about the criminal charges, he said, he didn’t understand: How do they figure we did anything wrong? But on April 11, after three months in the medical center, he turned himself in to the Presidio County Jail and was released on $10,000 bond. He returned to his family’s land, near the Gila Wilderness of western New Mexico.

He was still so weak he could scarcely move or eat. Every bite cramped his stomach. When his gallbladder failed, it was removed. Another three months passed before he was able to move around normally. Once Walker was feeling better, he and Ashley called off their engagement. “I was with him the entire hospital stay,” Ashley recalled, beginning to cry softly, “and he had a lot of draining bags and stuff coming out of his body for a really long time. I stayed with him until he got the last drainage bag pulled out of his body.”

The criminal charges against Michael and Walker made headlines not only in the United States but in Mexico and Canada. (In the January 2018 issue of Texas Monthly, the magazine gave the duo a Bum Steer Award for their role in the alleged “hoax.”) Sandy Wilson offered the brothers-in-law a deal of ten years of probation in exchange for a guilty plea.

The two decided to fight the charges together. Walker accepted that he had shot Edwin by accident, but he was certain Michael hadn’t shot him: the bullet entered Walker’s body from his right side, while Michael, it seemed, was to his left.

“Maybe a guilty person would take that plea deal,” Walker explained later. “But I ain’t guilty, and I don’t want to be treated guilty, and I don’t want that on my record.” If convicted, the men would forfeit their legal right to carry a firearm, ending their careers as hunting guides.

In March 2018, Wilson withdrew her offer of probation and presented the brothers-in-law with a far more punitive deal of ten years behind bars. That same month, Edwin and Carol filed a $1 million civil lawsuit naming several defendants they accused of negligence: Walker; Michael; Bob Daugherty, Walker and Morgan’s father (though he wasn’t at the ranch that night, he’d scheduled the hunt); the family’s outfitter business; and the owner of the Circle Dug. After the shooting, surgeons had carried out skin grafts and installed 28 screws in Edwin’s arm, in addition to a nine-inch titanium plate, which held together his radius bone. “My arm was hanging off like a piece of hamburger,” he said in a civil deposition in August 2018, adding that he’d lost the use of his right arm. “I have intense pain,” he said. “It’s to the point I don’t sleep at all.” Carol was also prescribed medication to help her sleep through recurring nightmares. She became her husband’s caregiver after his injuries, which had strained the marriage of the high school sweethearts.

The lawsuit rocked the Daughertys—Edwin had been a hunting client of Walker’s father for twenty years. But then a new finding upended the case once again.

Just a couple weeks before Edwin and Carol Roberts filed their suit, Michael and Walker’s criminal defense attorneys, Liz Rogers and Jaime Escuder, hired a ballistics expert to study X-rays of the bullet in Walker’s lung. The consultant, Richard N. Ernest, had supervised the firearms section of the Tarrant County Medical Examiner’s District, in Fort Worth, for nine years; he also owned Fort Worth–based Alliance Forensics Laboratory.

Ernest knew that Michael had fired his rifle at least three times that night. The weapon Michael used, an AR-15, is a .223-caliber, high-velocity rifle originally developed for the Army in the late fifties. It fires bullets that are less than a quarter of an inch in diameter, or narrower than a pencil.

As Ernest studied the X-rays, he realized the bullet in Walker’s left lung was almost twice the diameter, and up to three times the mass, of Michael’s .223 ammo.

The bullet had been damaged on impact, and Ernest was unable to precisely determine its original size. He could not rule out a .38 Special, which Morgan and Ashley were carrying at the Circle Dug, or a .357, which Edwin used to shoot the hole through the RV door.

Wilson, the district attorney, was dubious of Ernest’s assessment, questioning his radiological expertise. “They needed a radiologist who knows how to read an X-ray and understands the concept of how shadows enhance the size of the object,” she explained via email in August. In response, Ernest told me that he worked on the case with a radiologist and has decades of experience reading X-rays. “This type of examination is done in crime labs all the time,” he said. “It’s not something that’s new or novel.”

In the fall of 2018, Wilson recused herself from the criminal case; a new attorney on her staff had worked on the civil suit on behalf of the Circle Dug Ranch owner, which Wilson cited as a conflict of interest. Tonya Spaeth

Ahlschwede, who is based in the town of Mason, more than three hundred miles away from Presidio County, and serves as district attorney for the 452nd Judicial District, was appointed to prosecute the two men in Wilson’s stead. Ahlschwede’s office hired its own forensic specialist, Howard Ryan, a retired medical examiner and state police lieutenant from New Jersey, to assess Ernest’s report.

During a phone call on August 1, 2019, Ryan told prosecutors that Ernest had measured the bullet correctly. Ballistics experts for the defense and the prosecution were now in agreement: Michael, it seemed, had not shot Walker.

One month later, on a blazing-hot September morning at the Circle Dug, lawyers for the defense laid out their case directly to the prosecution. Rogers, accompanied by Walker, Michael, Morgan, and a family friend named A. Alan Griffin, a Houston oilman who had assisted Walker and Michael throughout their defense, guided two members of Ahlschwede’s staff around the stone house and up the front steps, re-creating the scene of the shooting. Not only did the ballistics report exonerate Michael, the lawyers argued, but there was no way Edwin could have shot Walker either. His RV, they argued to the prosecution, was swiping the retaining wall of the hunting lodge on Walker’s left, or to his east, when the bullet struck him from the west, where no one in the hunting party was at that moment. Ashley, who’d been right inside the front door at the time of the shooting, and Morgan, who’d been on the front porch, were never considered suspects. The bullet in Walker’s chest must have come from an intruder, the attorneys said.

Other details still didn’t add up. Walker was convinced someone fired on him while hiding by the west side of the house, where the ground is about six feet higher than the surrounding desert. This vantage point would have given the shooter a clear view as Walker was reaching the top of the stairs. But Border Patrol found no fresh tracks near that side of the house. They did encounter a three-foot-wide spatter of blood just below the steps, which led Nuñez to believe that Walker was shot there, rather than at the top of the steps. Walker and Michael insist the blood puddle belonged to Edwin, who was bleeding profusely from his arm. The investigators did not test the blood, but in Nuñez’s offense report, he stated that Morgan told him she saw Walker get shot at the bottom of the steps.

A contradiction in Morgan’s and Ashley’s witness statements created further confusion. The RV was initially parked about fifty feet east of the house’s front steps. During the shoot-out, it rolled past the steps and crashed into a boulder about fifty feet to the west. In her statement, Ashley said Walker was shot before she saw the RV driving by. From that direction, it would have been impossible for Edwin to shoot Walker. But Morgan’s statement described the RV passing the steps just prior to Walker’s shooting. In that event, Edwin would have been positioned west of Walker when Walker was shot from the west. However, Edwin has never been a suspect in the Circle Dug shoot-out and is not accused of any crime.

Walker’s absolution of Edwin aside, the bullets in the latter’s revolver raised more questions.

“I knew it was never Edwin that shot me,” Walker said. “The way he came through, it’s just physically impossible. He’d never get a shot off. And to be driving an RV at the same time with a shot-up arm, he had to be steering with one of them because one arm was shot. There’s just no possible way.” Walker also believes the bullet’s trajectory through his chest does not match an angle possible from the RV.

Walker’s absolution of Edwin aside, the bullets in the latter’s revolver raised more questions. In his only statement to law enforcement, Edwin described firing the gun just one time, through the RV’s door. When officers unloaded his .357 Magnum, a six-shooter with a steel barrel and wooden grip, they removed four live rounds from the cylinder and two empty cartridges—the gun had been fired not once but twice. And yet no member of the hunting party, including Edwin himself, recalled his shooting the revolver at any other time during his visit to the Circle Dug. Much later, in his civil deposition, Edwin would continue to insist that he had fired the gun just once and that no one else had used his weapon. But he could not account for the second shot.

Edwin further stated that no one from the offices of the Presidio County sheriff or district attorney ever questioned him about the spent bullet casing or any other matter. (Nuñez said he would have liked to speak with Edwin but did not have the opportunity.)

In early October, the acting district attorney dropped both charges of deadly conduct and aggravated assault against Walker and Michael. Nuñez was preparing evidence for a criminal trial when an investigator called him from the district attorney’s office. “It’s over,” the investigator told him. “It’s not going anywhere.” Walker was working in his shop when his attorney phoned to share the news. Walker immediately called Griffin. They cried together over the phone. The following spring, Edwin and Carol settled their civil lawsuit against the hunting guides for less than a quarter of the sum they’d sought. Although the shoot-out had garnered international media coverage in 2017, the local Big Bend Sentinel was the only newspaper to report that the case had been dismissed.

On a sun-bleached morning this May, the ocotillos and desert willows were blooming in vibrant hues of red and pink when I met Nuñez at his Presidio office. In addition to his full-time job as chief deputy of the sheriff’s department, Nuñez is the chief of police for the local school district. A wooden plaque on the wall behind his desk, presented by Sheriff Dominguez, commended Nuñez for coordinating the multiagency response to the Circle Dug shooting and for the personal risk he accepted on the night of January 6, 2017, when he alone responded to reports of shots fired at the isolated ranch.

Nuñez was still upset that the deadly conduct charges against the hunters were dropped. He believed he built a strong case. “This was clean and clear, open and shut. They pretty much admitted to everything that happened,” he said of the witness statements provided the morning after the shoot-out, which he said would lead any reasonable person to suspect that Michael had shot Walker. Not only was no trace of an intruder found at the ranch, he noted, but no member of the Circle Dug hunting party saw anyone else on the property that night. “Not one person saw anybody except each other,” he said. “But they assumed. They all assumed there was somebody there”—because Walker had said so, he added.

Five days after my visit with Nuñez, I drove to the Circle Dug to meet Walker.

He hadn’t been particularly eager to see me. He had never been interviewed about the shoot-out and wasn’t sure that talking to a journalist after all this time would do him any good. But when I arrived, there he was, a beanpole in a tattered baseball cap, with a toothy grin and a beard of blond scruff. He was standing beside the same gate that Nuñez rammed open that winter night in 2017. He unlocked it and shook my hand.

The drive from the gate to the Circle Dug headquarters was a bumpy twenty minutes of dirt roads and muddy crossings through Capote Creek, often dry but now puddled from spring rains. When we finally reached the headquarters, Morgan and Michael were hard at work reroofing the hunting lodge. Walker poured us coffee. We pulled chairs up to a patio table just a few feet from the location where the bullet struck him a few years back.

For the most part, Walker said, he had put the incident behind him. He told me he often forgets about the bullet left in his chest. Surgeries have cost him some of the strength in his core muscles, but he otherwise experiences no ill effects from the shooting. “You just kind of forget about it,” he said. “You know, out of sight, out of mind.”

Walker’s family and friends remained deeply aggrieved on his behalf, and Walker said the experience had made him leery of news media. “I always felt like reporters were doing it to make a political point, and I didn’t want to be used for that,” he said.

He also rejected the suggestion that he’d been itching for a fight after the home burglary—that he was prepared to “kill or be killed.” “It was never like that,” he said. “The last thing I would ever want to do is to pull a trigger, but when you’re shot at by someone else, that changes the story a little. People can speculate all they want and say what they would have done in that situation until they’re shot at, and your adrenaline goes through the roof.”

Members of the Daugherty family have not felt welcome in the Presidio area since the incident. (The manager of the Chinati Hot Springs, a nearby resort where I’d stayed the night before my meeting with Walker, scoffed when I mentioned the shoot-out: “Nothing has ever happened like that—ever,” she said, “so we all knew something else was up. There’s just no way.”) The family considered looking for a different hunting lease farther from the border, but they decided against it; Walker didn’t think that Big Rim Outfitters’ clients were in danger. “It was just a freak deal,” he said.

Walker poured me another cup of coffee. The sun had risen beyond the red-and-brown native rock walls of the ranch house as the desert heat took hold of the day. After we’d chatted for an hour or so, Walker asked me a question. “Tell me this,” he said. “How did you feel when you first heard the story? Like, what went through your mind? Did something sound fishy to you?”

In the days and weeks after the shooting, as news dribbled in, it had been easy to fill in the gaps with politically influenced assumptions. Inconvenient details were shaved from the edges. Culture warriors had shaped dueling narratives from an incident that, while horrific for the few people involved, would not have been a blip on the national consciousness if it had occurred anywhere but the U.S.-Mexico border. Even now, nearly five years later, the question of who shot Walker Daugherty still feels like a political Rorschach test.

Walker said he doesn’t speculate about the identity of the supposed intruders. He explained that while he’d assumed, in the moment, that the ranch was under attack by migrants, he’s perplexed by the unaccented English that Edwin heard through the RV door.

“We’ll never know,” he said, “because we don’t know who was here, and there was no evidence of them being here—besides the bullet in me.”

This article originally appeared in the October 2021 issue of Texas Monthly with the headline “Who Shot Walker Daugherty.” Subscribe today.

No comments:

Post a Comment