Dumba has spent her life performing in circuses around Europe, but in recent years animal rights activists have been campaigning to rescue her. When it looked like they might succeed, Dumba and her owners disappeared

When the family was at home, their “daughter” lived in an outdoor pen of about 500 sq metres – the size of two tennis courts – surrounded by an electric fence. To give Dumba exercise they would lead her into an adjacent patch of oak forest where she could forage and wander. Visiting the Kludskys in June 2018, the journalist Albert San Andrés found that the neighbours were delighted to have an elephant next door – their local “diva”, as one put it – and children would come out from the nearby town to see her. But the Kludskys told Andrés that animal rights activists were making the family’s life hell.

In the early 2010s, a Spanish animal rights organisation, Faada, had begun petitioning the Spanish authorities to take Dumba away from the Kludskys, on the basis that it was cruel to keep her in such a small enclosure with no other elephants for company. In 2014, the authorities duly inspected the property and recommended some improvements. The Kludskys, they said, should provide Dumba with shelter and a pond to bathe in, as well as more “environmental enrichment” – or psychological stimulation. Faada staff and volunteers continued to photograph and film Dumba from the Kludskys’ perimeter fence. There were further inspections culminating in a visit in July 2018, again commissioned by the authorities, of a team of experts in elephant welfare. They reported that, although Dumba now had a tent, her outdoor enclosure was too small, her shade was inadequate and she still had no bathing pool.

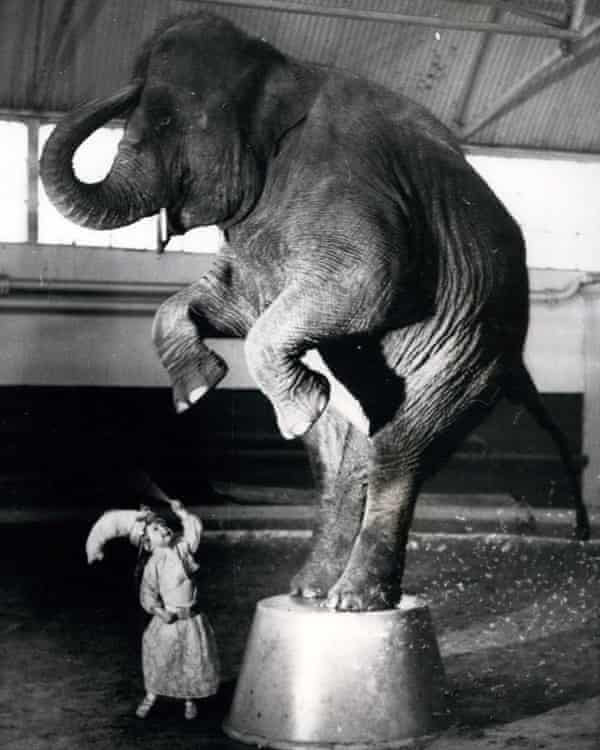

But the authorities took no action, and the Kludskys continued to tour in Spain and France, where circuses that feature animal acts can still draw a crowd. Kruse sometimes dressed up in sparkling gowns and turbans, and Dumba wore matching bracelets. At shows, the elephant, who weighs three and a half tonnes, would kneel on command and stand on her hind legs. She twirled her trunk and drop-kicked balls for treats, then posed for photos at €10 a go.

In recent years, circus families like the Kludskys have come under increasing pressure as public opinion has turned against the use of wild animals for entertainment. Today, many circus elephants in Europe are reaching old age. Campaigners want them placed in specially built sanctuaries, where they can enjoy retirement with their own kind. But their owners insist that for the elephants, being separated from their human “families” would be traumatic. The Kludskys and their supporters feel they are accused of cruelty by people who know nothing about the lifelong bond between elephants and their trainers, or the elephant’s pleasure in learning new tricks. The two sides are implacably opposed.

When Covid-19 broke out across Europe, the Kludskys left a circus in Zaragoza to sit out the pandemic at home. There was no more work but, while Spain was under strict lockdown, at least there was no more scrutiny either. They shielded: Kruse took care of the shopping while George went no further than the nearest farm to fetch Dumba’s hay. Then, in August 2020, Faada changed tack. Instead of focusing on Dumba’s welfare, they turned their attention to the risk Dumba might pose to the public.

The organisation told Spanish authorities that the Kludskys were breaching security regulations. An elephant, being a potentially dangerous animal, had to be enclosed by a thick-barred steel fence. But the local council refused the Kludskys permission to build an unsightly elephant fence in a scenic rural zone. That was the double bind the family found itself in last September. And that’s when they decided that their next act would be to disappear. They stocked up Dumba’s trailer with hay, filled the water tank, loaded her in and heaved up the ramp behind her. Then they nosed the truck slowly out of the gate and travelled north.

When Faada campaigners learned what had happened, they were furious. On 27 September, the group lambasted the Spanish authorities on Twitter for their inertia. In failing to confiscate the elephant, they argued, the authorities had forfeited Dumba’s last chance to see out her final years in peace and comfort. Míriam Martínez, the head of Faada’s wild animal division, was upset that the Kludskys had given them the slip. “We did not want that to happen,” she said, gravely. But she knew the elephant couldn’t stay hidden for long.

Alorry carrying an elephant doesn’t move very fast. Still, it took no more than a day to travel the 400km to the Kludskys’ destination, crossing from Spain into France just south of Perpignan and hugging the Mediterranean coast as far as Montpellier, before travelling north into the rural Gard region. When they rolled into the tiny village of Euzet, in the foothills of the Cévennes mountain range, the locals were expecting them.

“I was informed that the elephant was going to be here about 28 September,” Cyril Ozil, mayor of Euzet, told me recently. It had been Ozil’s responsibility to check that the paperwork for a wild animal in transit was in order. He knew the family had a friend living locally and had come through with Dumba before. The Kludskys set up camp on their friend’s 30-hectare property, parking their unmarked trailer next to Dumba’s tent.

The Kludskys settled into a new rhythm. Each day, George and Martyn accompanied their friend on a tractor to fetch hay from the next village. Dumba eats around 65kg of it a day, supplemented by alfalfa, cereals, vegetables and fruit. She is a picky eater, but loves bananas, which she eats by the bunch. The Kludskys took her for daily walks, having the run of their friend’s fields, vineyards, olive groves and woods. When necessary they guided Dumba with the elephant keeper’s traditional tool, the ankus, essentially a pointed stick with a hook. Most of the time, though, Kruse said Dumba chose where to go. Occasionally, she stopped to tear up tufts of grass with her trunk, or snap off branches of evergreen oak. At night, Yvonne and George slept in the house while Martyn bedded down next to Dumba in the tent. “She is used to having at least one of us nearby,” Kruse told me.

The Kludskys had hoped to find work in a zoo or safari park, then think about selling the Caldes property to buy another where they could live legally with Dumba. “We did not count on Covid complicating our lives so very much,” Kruse said. When a new lockdown began in October, they hunkered down.

Euzet, which has about 450 inhabitants, is a slash of limestone against a mat of dark green. The locals are taiseux – they don’t say much – and they have a tradition of supporting the underdog. For months, word of Dumba’s presence did not spread far beyond the village. But then, when they were out for their stroll one day in early January, the Kludskys came across some hikers. By the nature of their questions, Kruse guessed that one of them was an animal rights activist. “I remember saying to my husband at the time, ‘Oh here we go, that’s the end of our peace and quiet,’ and sure enough I was right. It was the beginning of a very vocal, organised and international campaign against us,” she told me.

On 18 January, One Voice, a French organisation that works with Faada, announced to their followers on Twitter: “We have found Dumba on a rubbish tip in the Gard. Exploited, kept in a lorry, her life is emblematic of every circus animal’s … this suffering must stop!” The organisation filed a complaint to the public prosecutor in the nearby town of Alès, citing animal mistreatment. Having ordered a veterinary inspection, the prosecutor declared himself satisfied that the elephant was well cared for, but he didn’t publish the vet’s report – and despite pressure from One Voice, he still hasn’t.

Frustrated by the prosecutor’s failure to act, One Voice commissioned other vets to examine video footage of Dumba. The vets had some concerns about her health: she was too thin, had dry, scurfy skin and was probably suffering from joint pain, they said. The pop star Cher, who co-founded the animal welfare charity Free the Wild, wrote to the French minister Barbara Pompili, who was deliberating on whether to ban wild animals in circuses, asking her to end Dumba’s “daily torment”. Pompili replied, expressing noncommittal sympathy (“a judicial inquiry is under way”).

People dug up old photos of the family going about their business, and posted their protests on social media: “This is #Dumba being hosed down in a parking lot. Seriously? Concrete for an elephant you have already crippled? Just another example of how Dumba is being abused by the Kludskys and their pathetic staff, we need to get her away from them now.”

Once the family’s location had been made public, a steady stream of journalists and the simply curious tramped out to Dumba’s camp, just beyond the village proper, and the Kludskys greeted them politely. When I turned up in early February, Kruse was cordial, if a little wary. It was a cool, sunny afternoon. Emerging from the transporter’s cab wearing jeans and a warm jacket, she led me inside the tent and up to the electric wire that marked off the elephant’s 10 x 8 metre pen. Instinctively, as Dumba’s trainer, she placed herself between the animal and her audience. Female Asian elephants have a reputation for moodiness, but everyone I have spoken to who has met Dumba has described her as calm and docile.

She is nearly 3 metres tall. I gazed up into her amber eyes, and she flapped her ears and waved her trunk, which like her ears is speckled pink, in what seemed like a joyful welcome. George – diminutive, muscular, all smiles – climbed down from the trailer to say hello. Czech by origin, he let his wife do the talking, and by then her talk was resentful. When Dumba lifted one foot, as if offering to shake hands, Yvonne clicked her tongue. “They’ll tell you she does that because it relieves her joint pain,” she said, referring to the animal rights activists. “But we taught her that trick years ago.” She blamed One Voice for putting her family’s health at risk by undermining their attempts to shield from Covid.

It’s hard for a non-expert to know if an elephant is healthy or happy, but mayor Ozil – no expert himself, he’s quick to admit – was present during the official vet’s inspection that took place while Dumba was in Euzet. “If the vet had confirmed the association’s charges, I would have been the first to ensure that she was removed from her jailers,” he said. “That wasn’t the case.”

By then, his office was receiving hate mail. “Please let Mayor Cyril Ozil know how you feel about his complacency with Dumba’s suffering and his support towards Dumba’s abusers,” one animal rights campaigner tweeted on 26 January. The residents of Euzet did not appreciate this, or the false media reports that Dumba was living in a landfill and that the Kludskys had fled a lawsuit for animal mistreatment in Spain. “Everyone in Euzet who saw the elephant was shocked by what they read in the press,” Ozil said. Many locals felt that the harried family should be left in peace.

While One Voice’s complaint was being investigated, the Kludskys had to stay in Euzet, but on 20 February, shortly after the complaint was dismissed, they vanished again – leaving just a square of yellowed grass where Dumba’s tent had been. A day or two later, Ozil received a text message saying that they had arrived safely at their new destination: “Dumba ate almost the whole way as usual … Thank you for everything. Yvonne, George and Martyn.” Even if Ozil knew where they’d gone, he told me, he wouldn’t say.

As something close to circus royalty, Yvonne Kruse represents a proud tradition brought low in the court of public opinion. In 2021, she is a pariah, but 70 years ago, her parents were the height of glamour. Kruse’s Swedish-born father, Gösta Kruse, trained elephants for the Bertram Mills Circus, the UK’s biggest postwar circus, in its big-top heyday of the 50s and 60s. The high point of his career, he wrote in his memoir Trunk Call, came in 1952, when a young Queen Elizabeth II watched his elephants perform at London’s Olympia. Kruse’s mother, Liverpudlian Joan Fowles, also worked for the same circus – her speciality was riding cantering horses standing up, each foot on the back of a different horse – and on the day the couple married in Southport, then part of Lancashire, in 1955, they rode past admiring crowds on an elephant named Jennie. A year later, their daughter Yvonne was born. An elephant pushed her pram, and she was photographed aged two with three of them stacked above her.

But around the time the Bertram Mills Circus was drawing its biggest crowds, a quiet revolution was beginning in the science of animal cognition. Studies were leading to the recognition that some animal species were capable of complex mental operations and feelings. They were not as different from humans as had once been thought. Over the next few decades, observers of elephant behaviour discovered that elephants can identify each other at up to 2km distance, by picking up very low-frequency sounds. They reported that an adult female knows the voices of up to 100 others, and remembers them for years. A daughter stays with her mother until her death, which she grieves – guarding the body in silence, for example, or covering it with leaves. Elephants are empathic and loyal, intelligent and sociable. They’re also self-aware, being among the few big-brained animals that can recognise themselves in a mirror. And though elephants have been tamed, they have never been domesticated in the sense of being selectively bred, like dogs or horses. “Tamed” is a relative term, too: “They can’t habituate to small spaces,” says the elephant researcher Joyce Poole.

These revelations jarred with people’s knowledge of how circus animals were kept, and the cruel way in which they were often taken from their mothers in infancy and kept in isolation. In the UK, which led the way in changing public perceptions, there were orchestrated campaigns against animal acts in circuses from the early 80s. Circus supremo Gerry Cottle, whose first job was “shovelling up elephant shit”, sold his last elephant in 1993 and eventually supported a ban, on the grounds that animal acts were now giving circus a bad name. That ban, the Wild Animals in Circuses Act 2019, came into effect last year. Dozens of European countries have now prohibited wild animals in circuses. Germany and Spain are notable exceptions, with local but not nationwide bans, while France announced last year that it would phase out animals in travelling circuses.

The problem is what to do with the animals that remain. According to the European Elephant Group (EEG), based in Germany, there are just shy of 100 circus elephants left in Europe. Elephants can live to 70, though their life expectancy tends to be significantly shorter in captivity. Most that remain in Europe are middle-aged or older. These are the animals that concern Muriel Arnal, the president of One Voice. She is now in her 50s, and lives in Brittany. Her passion for rescuing began when she was on holiday at the French seaside aged about 10, and saw an elephant in a parked circus lorry. The presence of a large, exotic animal in a cage shocked her. “Every day I filled my backpack with bread and walked 2 or 3km to give it to him,” she told me. Though she studied business administration at university, when it came to choosing a career she decided to follow her idol, Dian Fossey, and devote her life to animals.

Arnal set up One Voice in 1995, and scored a notable victory five years later when she had a chimpanzee called Achille removed from a circus and sent to an ape sanctuary. After that, she turned her attention to lions, tigers and elephants. Today, One Voice has about 17,000 supporters, whom she refers to as “non-violent warriors”, and she campaigns tirelessly against animal cruelty in any form – hunting, fur, experimentation, circuses. She wants France to ban animal performing of all kinds, not just travelling circuses. There is something quasi-religious about the way Arnal discusses her calling; she talks a lot, patiently and calmly, about the “martyrdom” of animals, and their “despair”.

While Arnal considers people who make their living from performing animals unfit to look after them, William Kerwich, president of the French union representing animal trainers, insists no one is better qualified to care for an animal than the trainer who has known it all its life. He is deeply suspicious of the do-gooders who set up animal retirement homes paid for by donations from a public who, he suggests, have been duped into thinking that all circus folk are animal torturers. “If there were to be a ban – and we’re not there yet – it is out of the question that our animals should go to a sanctuary where there is no one competent to look after them,” he said. The union, Kerwich told me, was standing squarely behind Yvonne Kruse.

What ageing elephants need, says Scott Blais, is space, autonomy and the company of other elephants. Blais, who set up a sanctuary in Tennessee in 1995 and another in Brazil in 2016, keeps elephants in a setting as close as possible to conditions in the wild, and says previous owners who have returned to visit their old elephants often marvel at their transformation. It was at the Tennessee sanctuary that workers witnessed the extraordinary reunion of two former circus elephants, Shirley and Jenny, in 1999. The two had spent one season together at a circus when Jenny was a calf. After a separation of more than 20 years, they recognised each other and bent the steel bars of an elephant fence in their eagerness to get close to each other. They became inseparable, and for seven years, until Jenny died in 2006, their relationship was like that of mother and daughter.

Elephants have shown they can retain a bond with humans, too. Joyce Poole recalled her reunion with a wild African elephant after 12 years. When she called out to him, he recognised her voice, walked up to her car window, and “allowed her to touch him”, she said. Elephants also kill humans, in captivity and in their ever-shrinking natural habitat, but these numbers are tiny compared to the numbers of elephants killed by humans each year.

‘Where is Dumba now?” pleaded a One Voice supporter on Twitter on 21 March. “Is there any way to know if she is safe?” It was a month since the Kludskys had left Euzet. It wasn’t just animal rights activists who wanted to know where the Kludskys and Dumba had gone. So, too, did the couple behind a new elephant sanctuary in south-west France.

In 2011, seeing that bans on wild animals in circuses were looming across Europe and realising that rescued animals would need somewhere to go, two Belgian elephant keepers at Antwerp zoo decided to set up the continent’s first elephant sanctuary. Supported by donations, including from animal protection organisations such as One Voice and the Brigitte Bardot Foundation, Sofie Goetghebeur and her partner, Tony Verhulst, bought 28 hectares of rolling woodland in France’s Périgord-Limousin regional natural park, and created Elephant Haven.

The first phase of the sanctuary’s construction was completed in July 2020, and when I visited recently, Goetghebeur and Verhulst gave me a tour. The design of Elephant Haven is based on what science tells us about how best to manage elephants in captivity. There is a large wooden barn big enough to accommodate three elephants, complete with an elephant fence, a thick carpet of sand and a dispensary for medical attention. Seven hectares of the property have been fenced off for elephants to roam in, and video surveillance has been installed. There is an orchard to supply the elephants with fruit, and an underground spring, which is important as elephants can drink more than 100 litres a day, and like to bathe. There are mud pools for wallowing, and log walls for back-scratching.

There is just one problem: there are no elephants. Ten years after their dream was conceived, Goetghebeur and Verhulst have no rescues to show for it. They knew that the first elephant would be the hardest. An elephant’s human “family” was bound to be reluctant to part with it if the sanctuary had no elephant company to offer. But isolated in their rural idyll, Goetghebeur and Verhulst, who are not yet 50, seemed tired and demoralised. Their sponsors, they admitted, were getting impatient. “Everyone wants to know when the elephants will come,” Goetghebeur sighed.

For years, she and Verhulst tried to make contact with the Freiwald circus family in the Netherlands, owners of that country’s most famous elephant, Buba, but they never got a reply. The Dutch banned wild animals from circuses in 2015, but an exception was made for Buba because at the time there was no obvious home for her. Last December, after a political tussle involving the Dutch agriculture minister, it was decided that Buba should remain with the Freiwalds.

The pair had no more luck with Longleat safari park in the UK, which they hoped to persuade to part with its only elephant, Anne, who is in her 60s or possibly even older. In 2011, Anne was removed from a site near Peterborough belonging to a circus, after an organisation called Animal Defenders International secretly filmed her being beaten by a handler. Longleat took her in, and 10 years later she is still there, pampered but with no company apart from three Nubian goats.

Anne’s rescue had been organised by vet Jonathan Cracknell, who told me her previous owner continued to worry about her welfare long after he had been convicted of maltreating her. “If the weather forecast said rain, he’d ring up and give my team advice,” he said. (The judge acknowledged that the owner loved animals and that he had not been aware of the abuse.) Cracknell left Longleat in 2016, since when a small grassroots group called Action for Elephants UK has been lobbying Longleat to release Anne to the French sanctuary, but so far the safari park has resisted all such calls. In a statement, Longleat warned of the high risks involved in “uprooting her from familiar surroundings and people she has learned to trust, and transporting her to a new, unknown location with the prospect of being left in the company of other elephants she does not know”.

Anne often sways – a form of repetitive behaviour indicating psychological disturbance, thought to stem from past bullying by humans and other elephants. Joyce Poole, who has studied elephants in the wild for more than 40 years, told me there was no reason Anne couldn’t still form an attachment to another elephant, as long as the introductions were handled properly. But there is also her advanced age to consider: if she were to die en route to France, Longleat would probably get the blame. It’s genuinely difficult to know what’s best for Anne now, said Cracknell.

When I visited Goetghebeur and Verhulst in March, they were still hoping to bring Anne and Dumba to Elephant Haven. But their approaches to Kruse – through Facebook, and a letter delivered via an intermediary – were met with silence. Goetghebeur and Verhulst realised they were up against a “gentleman’s agreement” within the circus community not to send them an animal. As far as Kruse was concerned, Elephant Haven was backed by people who had tried to “kidnap” Dumba.

As I was leaving the sanctuary, Verhulst shared a last thought: “The worst thing is they argue they are really attached to her, but she is for sale. You can buy Dumba if you want.” Photographs and emails have circulated online suggesting that Dumba was for sale as recently as September 2020, for €180,000. When I asked Kruse about this, she denied it. “We were offered €200,000 some years ago but declined. That is not our way.”

Whatever the truth, Kruse’s claim that she loves Dumba like a daughter is certainly complicated by the fact that the elephant is the family’s main source of income. “Yes the animals are dear in the dollar sense, but that’s all,” said Arnal. “The trainers who mistreat them and keep them in abject conditions – as in Dumba’s case – have no affection for them.”

Kruse said in an email to me that Covid had been a financial disaster for the family. They had had no government support and were living off savings and the generosity of family and friends. “I find it ironic,” she said, “that the associations which are supposedly trying to help and save the animals never once got in contact with us to offer a bale of hay or sack of carrots.”

Over the first weekend in April, news broke that Dumba had resurfaced in Germany. After the Kludskys left Euzet, Muriel Arnal told me, One Voice had dispatched investigators to tail their vehicle. “We had lost Dumba once, it was out of the question that we should lose her again,” she said. On 2 April, they announced the elephant’s new whereabouts: the Kludskys had left Dumba in a wildlife park between Berlin and Hamburg. The photo the organisation released seemed to show Dumba in a bare prison cell – though the bars containing her were those of an elephant fence, the likes of which the Spanish authorities had demanded the Kludskys install in Caldes.

Dumba’s new home, the Elefantenhof Platschow, is run by Sonni Frankello, scion of a German circus dynasty. Comprising an old farm with stables, barns and green space, it hosts a range of animals including a dozen elephants, which occupy three of its seven hectares. The public pays to see, feed and ride the elephants, and though the animals don’t tour, they do perform and they can be hired out for events.

The Kludskys stayed with Frankello’s family for 10 days in late February – “to see that the transition went smoothly”, Kruse said – then returned home to Spain to allow Dumba to complete her integration. By the time they left, Kruse and Frankello said Dumba had started bonding with another elephant called Susi who arrived at around the same time, from a Spanish circus. The two were introduced via a shared paddock where a cable separated them initially, until it was considered safe to remove it. By early April, Dumba and Susi were mixing freely, and being introduced slowly to some of the other elephants.

Neither Kruse nor Frankello would say if Frankello had paid for Dumba, but Kruse told me the move was permanent – that they had done what they thought was best for Dumba, in the circumstances – and that her family were desperately missing their daughter: “The first cut of hay in the fields, not having to buy all those apples and carrots when I go shopping, not being able to sit by her when reading or my husband not going for a last muck out, more hay for the night and a cuddle around midnight remind us constantly of our loss.”

One Voice is keeping up its campaign for Kruse to be prosecuted for mistreatment. They are still trying to persuade the Alès prosecutor to publish the report of the vet who inspected Dumba in Euzet, so that they can use it to support the lawsuit. While Dumba continues to suffer, Arnal told me, they won’t give up. On the Kludskys’ side, Kerwich, the animal trainers’ representative in France, used the same words – “On ne lachera pas” – we won’t give up.

When he felt she was ready, Frankello planned to resume teaching Dumba to perform tricks, adapting to her age and aptitudes. “I know she is good at football,” he said. “She is also very good with her trunk, so perhaps I’ll teach her to do jigsaw puzzles.” Like many circus people, Frankello sees training as the highest form of enrichment, and believes that circus elephants get mental stimulation from performance and enjoy attention and applause. Covid rules were strict this spring, in the German state where the Elefantenhof is situated, and he had weeks to hone her drop-kick before the first vaccinated visitors arrived in May, to watch and laugh and clap.

No comments:

Post a Comment