Portrait of David Livingstone. Image: Wiki Commons

***

The plan was insane. After months of dehydrating himself through the Kalahari Desert, David Livingstone planned to ride his plodding white ox named Sinbad from the Chobe River to Luanda – from the eastern tip of the Caprivi Strip to the Atlantic Ocean. Then he would walk right across to the Indian Ocean.

Nobody he knew of had done such a daring trip. He had no idea if rivers, lakes or hostile tribes blocked the way. Traders, he would write, had told him there were many English in Luanda. “Thither I prepared to go,” he wrote, “and the prospect of meeting with countrymen seemed to overbalance the toils of the longer march.” That was odd, considering that he spent most of his life in Africa avoiding his fellow countrymen.

The party – Livingstone and 27 Makololo porters – had three muskets, a rifle and a double-barrelled shotgun plus 10 kilos of beads, a small tent, a sheepskin blanket, a horse rug, some tea, coffee and sugar, a sextant and some spare clothes “to be used when we reached civilised life”.

“I had always found,” he commented, “that the art of successful travel consisted in taking as few impedimenta as possible.” One wonders, then, why he needed so many porters.

His trip to Luanda nearly killed him, but by 1855 he was back at Linyanti, nearly 4,000km later. The die was cast: Livingstone set eastwards to complete his walk clear across Africa, from west to east, one of the 19th century’s greatest feats of exploration.

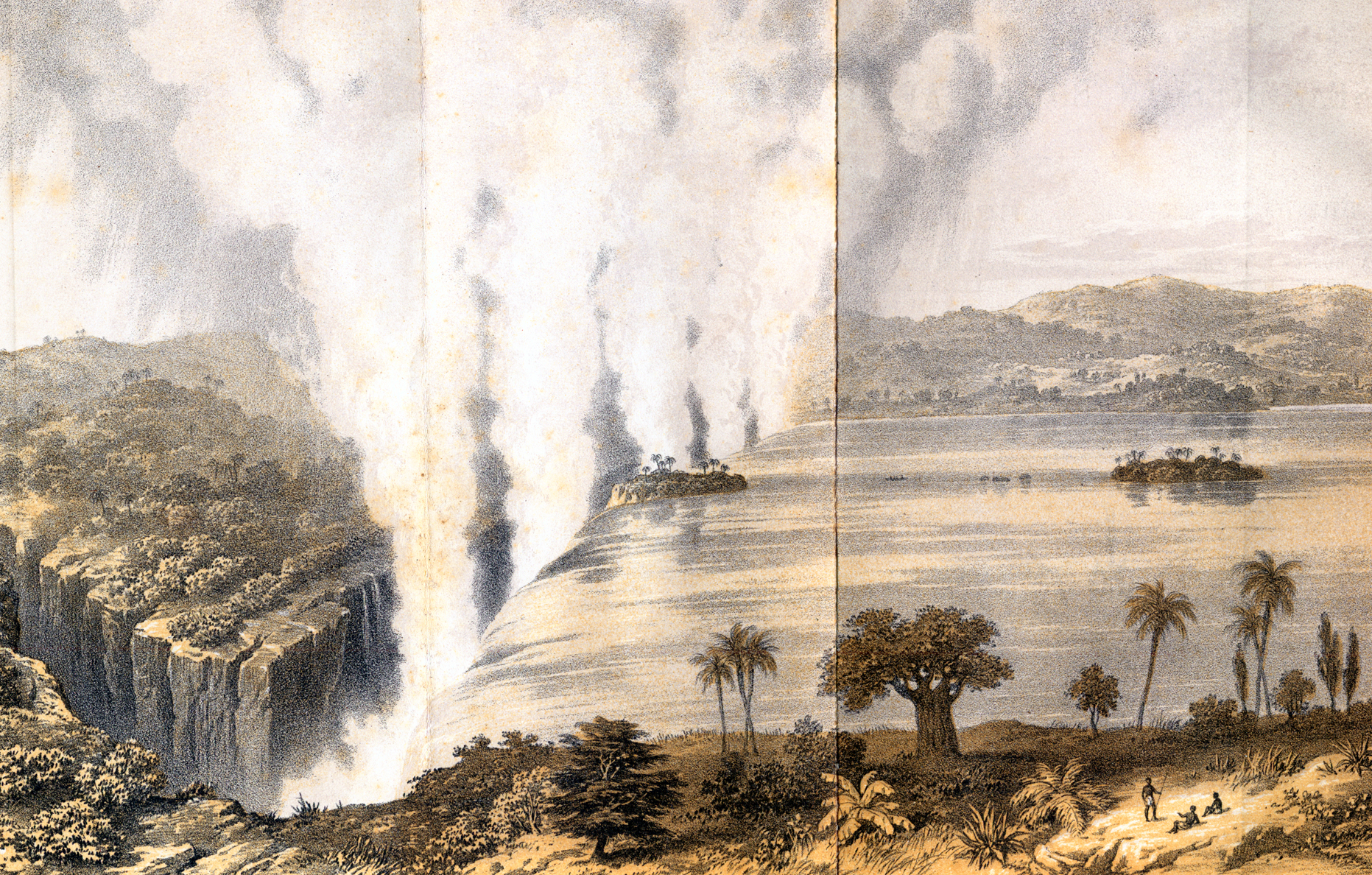

He decided to travel on the north bank of the Zambezi under the impression that Tete, the farthest Portuguese inland station, was on that side (it wasn’t). Accompanied by Chief Sekeletu of the Makololo, Livingstone headed downriver by canoe. Soon after leaving, the chief asked Livingstone: “Have you smoke that thunders in your country?” He pointed at columns of vapour rising into the blue sky, their summits seeming to mingle with the clouds. Livingstone soon heard a dull roar, and the boatmen brought them to an island in the middle of the river “on the very edge of the lip over which the water rolls”. They stood and stared at the boiling torrent below them.

In his travels, the missionary almost always noted and respected local names of rivers, mountains and areas. But when he beheld the great falls on the Zambezi, he was so awestruck he departed from this policy and named them after Queen Victoria.

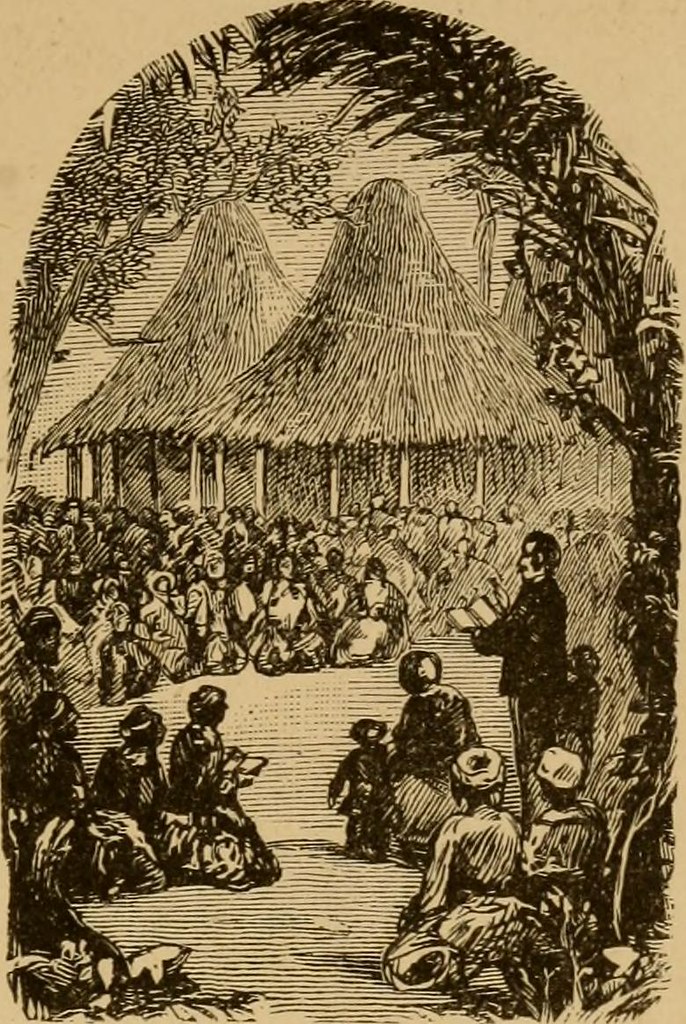

Livingstone was a marvellously perceptive ethnographer and naturalist. Plodding down the river, he took time – sometimes days – to question people about their customs, or to note species, often drawing them with meticulous care.

When he met the Batoka at the Kafue, however, their lack of front teeth startled him. They had them knocked out at puberty, and considered anyone with front teeth to be ugly. When he asked the reason, the Batoka told him “they wished to look like oxen, and not like zebras”. The answer left him even more puzzled.

As Livingstone dropped down the valley, he speculated on the food value of maneki fruit and the seeds of nux vomica; watched in amazement as mopane trees folded their leaves, presenting the smallest surface to harsh sunlight; experimented with the navigation abilities of soldier ants, concluding (quite rightly) that they tracked by scent; watched “plasterer” wasps stunning creatures in which to lay their eggs.

He filled pages of his diary on the environmental value of termites; noted the diets of oxpecker birds; turned “with a feeling of sickness unrelieved by the recollection that the ivory was mine” when his men killed an elephant and followed honey guides to see if they really led to honey (they did – 114 times to hives and only once to an elephant).

His legendary cool saved him when a band brandishing battle axes threatened his party. A warrior, howling and in a frenzy – his eyes protruding, his lips covered in foam – advanced on the missionary, axe raised.

“I felt some alarm,” he wrote, “but disguised it from the spectators, and kept a sharp lookout on the battle axe. After my courage had been sufficiently tested, I beckoned to the others to remove him… I should like to have felt his pulse to ascertain whether the violent trembling were not feigned.”

Several days downriver from the Luangwa River his party had been threatened by warriors under Chief Mpende. The missionary roasted an ox and sent a hind leg to the chief. Mpende responded with friendship, saying a mozunga (Portuguese), his enemy, would never have done such a thing.

“All the slaves of Tete are our children,” he told Livingstone. “The Bazunga have made a town at our expense.” The chief lent them canoes to cross to the south bank, where Livingstone had been told the tribes were friendlier. Several years later he would regret that route for what he failed to see.

Travelling southeast through forests, he was amazed at the “hum of insect joy” all about. “The universality of organic life,” he told his diary, “seems like a mantle of happy existence encircling the world.” Of the birds he exclaimed: “These African birds have not been wanting in song so much as in poets to sing their praises.”

One night Livingstone’s party was surrounded by soldiers, who turned out to be from Tete. As luck would have it, they were friendly. Next morning the soldiers cooked up “the most refreshing breakfast I ever partook of” then they all headed downriver to the Portuguese settlement. He found Tete “in a lamentable state”. What he had missed in his more southerly route (with unforeseen consequences), were the terrible Cahora Bassa rapids.

In Tete Livingstone heard talk of a river named Shire which, it was said, drained a great lake, the Nyanja. He logged this information for future use and journeyed down the river past Senna to the Zambezi Delta, then northeast to Quelimane on the Indian Ocean coast, which he reached in May 1856.

It was four years since he left Cape Town, three since he had heard from his family in England. He caught a sailing ship to Mauritius, then hitched a ride home to England on the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Ship Company vessel Candia. There he received a hero’s welcome but found his family impoverished, his wife, Mary, a virtual alcoholic. A bestselling book later, he was back in Africa where he would eventually die in a swamp. DM/ML

No comments:

Post a Comment