Adapted from Rock Me on the Water, HarperCollins Publishers, 2021.

When cbs first placed All in the Family on the air, on January 12, 1971, it irrevocably transformed television. After a shaky first season in which it struggled to find an audience, the show prospered, rising to become No. 1 in the ratings for five consecutive years, a record unmatched at the time. All in the Family commanded national attention to a degree almost impossible to imagine in today’s fractionated entertainment landscape. Archie Bunker’s catchwords—stifle, meathead, and dingbat—all became national shorthand. Scholars earnestly debated whether the show punctured or promoted bigotry.

Its success not only helped lift The Mary Tyler Moore Show, M*A*S*H, and the other great topical comedies of the early 1970s, but also cemented the idea that television could be used to comment meaningfully on the society around it—an idea the networks had uniformly rejected throughout all the upheaval of the 1960s. That legacy—the determination to connect the medium to the moment—reverberates through shows as diverse as Fleabag, Atlanta, Breaking Bad, The Wire, and countless others. The night that CBS initially aired All in the Family was the first step on the road toward the Peak TV that we are living through today.

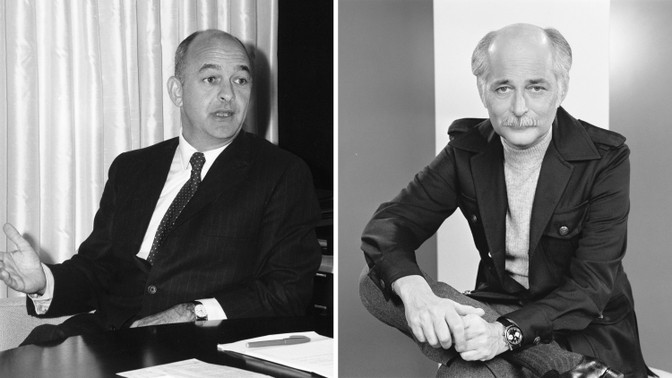

Initially, though, it was something of a miracle that All in the Family reached the air at all. Before CBS bought it, ABC had rejected it twice. And before All in the Family, shows that tried to achieve more relevance had almost all failed, mostly because they were too laden with good intentions to attract an audience. That All in the Family not only reached the air but prospered was the result of two men: Norman Lear, its staunchly liberal creator, and Robert D. Wood, the conservative president of CBS, who put it on the schedule. That act revolutionized television, but both men were unlikely revolutionaries.

Norman lear was the son of a man whose dreams dissolved quickly but whose resentments outlived him in the work of his son. Herman Lear was a small-time salesman and entrepreneur, and a fountain of dubious get-rich-quick schemes. His wife, Jeanette, according to Norman, was self-absorbed, discontented, and, like her husband, volatile. Later, they would become Lear’s early models for Archie and Edith Bunker. Throughout his childhood in Connecticut and Brooklyn, Lear’s parents immersed him in an environment of barely controlled chaos. The two of them, Lear would often say, “lived at the ends of their nerves and the tops of their lungs.” At the peak of argument, the veins in his neck bulging, Lear’s father would beat his fists against his chest and bellow at Lear’s mother, “Jeanette, stifle yourself.”

Like many children of the Great Depression, Lear found direction and structure in the military. After drifting through a few semesters at Emerson College, in Boston, he enlisted in the Army Air Force following Pearl Harbor and flew dozens of bombing missions over Germany. After a few years working as a Broadway press agent and, later, for his father, Lear made a decision that proved a turning point: He loaded his wife and infant daughter into a 1946 Oldsmobile convertible and pointed it toward Los Angeles. There, he hoped for a fresh start, but struggled to find work. He was reduced to selling furniture and baby photos door-to-door with a man named Ed Simmons, an aspiring comedy writer who was the husband of Lear’s cousin.

Through the 1950s, Lear’s career advanced in step with the growth of television itself. These were the years of television’s so-called golden age, when earnest dramas such as The Philco Television Playhouse groomed a steady stream of young directors for Hollywood. Lear marinated in the other great television product of those years: the star-led variety shows, such as Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows, that drew on traditions of vaudeville and radio comedy.

Lear thrived in this world. He began to ricochet between Los Angeles and New York, mastering the breakneck pace of television production—he survived the constant deadlines, he later recalled, on Dexedrine to stay awake for all-night writing sessions and Seconal to sleep when they were over. He honed his sense of comedy, absorbing the rhythms of sketches that had to quickly grip an audience’s attention between singers and dancing acts.

Some of these films (including Come Blow Your Horn and Divorce American Style) managed respectable box-office returns, but none generated much critical excitement. No reviewers saw in the Lear and Yorkin movies, or their succession of television specials with soft-edged mainstream entertainers, the profile of anything new. Looking back, one Hollywood executive described them in those years as “yeoman producers, just guys that would get their heads down and do the work.” Little of Lear’s work in the 1960s signaled that he had much to say about the way America was transforming around him. “Here’s an example, and it rarely happens, of a guy who was smarter than his career,” recalled Michael Ovitz, a co-founder of Creative Artists Agency. “Norman Lear was far more intellectually proficient than the things he was doing.”

Within a few years, millions would agree, but not until Lear met another World War II veteran who was an even more unlikely candidate to transform the nature of television.

The career of robert d. wood, the CBS executive who ultimately put All in the Family on the air, proceeded almost exactly in parallel with Lear’s. While Lear served in the Army Air Force during World War II, Wood spent three years in the Navy, including time in the South Pacific. After the war, he graduated with a degree in advertising from the University of Southern California in 1949, the same year Lear arrived in Los Angeles with his young family.

Wood started his career in ad sales for the CBS radio affiliate in L.A., KNX. By 1960, he’d risen up the ranks to become vice president and manager of the network’s local television affiliate. His elevation to that role anointed him as a prince in the CBS empire. The affiliate, KNXT, was one of the five TV stations around the country that the federal government permitted CBS to own and operate directly during this period. These “O&O stations” were concentrated in the largest markets and generated enormous profits. CBS granted great autonomy to O&O general managers like Wood and marked them as future leaders. The network also pushed managers to deliver on-air editorials, like those in local newspapers, but left them almost entirely free to decide the content.

Wood was a gregarious boss, with a salesman’s effortless capacity to make friends and create camaraderie. He knew everybody’s name and had time to talk to anyone. “Didn’t matter who they were … he was your buddy,” Williams said. Wood’s politics were consistently conservative, reflecting the center of gravity in L.A. media and business circles during the 1950s and ’60s, in which he mingled easily. In 1962 and 1966, respectively, KNXT endorsed Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan for governor. In 1964, when the first demonstrations by the free-speech movement erupted at UC Berkeley, Wood, in one of his on-air editorials, called the demonstrators “witless agitators” and insisted that they “be dealt with quickly and severely to set an example for all time to those who agitate for the sake of agitation.”

This promotion placed him atop the most powerful and profitable of the three television networks. CBS’s preeminence was symbolized by its imposing Midtown Manhattan headquarters, an austere and dramatic spire of charcoal-gray granite known as Black Rock. From his 34th-floor office, Wood entered a Mad Men environment that appeared frozen in time. This was a more urbane, cosmopolitan, and cutthroat world than the domesticated cycle of Junior League dinners and weekends at the beach that Wood had left behind in Los Angeles. But he took to it naturally. To many around him, Wood came across as the West Coast equivalent of an Ivy Leaguer, confident and smooth, if no intellectual; he was always more comfortable discussing football than philosophy.

But for all the power and profitability that CBS projected through the late ’60s, it couldn’t entirely ignore the social changes of the era. CBS faced disruption from the same demographic-driven transformation of its audience that had staggered the movie studios and sent weekly admissions in movie theaters plummeting through the ’50s and ’60s. Like Hollywood, the television networks faced a growing disconnection between their musty products and the young Baby Boomers whose swelling numbers and growing buying power were reshaping the market for popular culture. And Wood, with his grounding in Los Angeles, felt the tremors earlier than almost anyone else around him.

In 1961, newton minow, the chairman of the Federal Communications Commission, disparaged television as “a vast wasteland.” But he would have been just as accurate to call it “a vast cornfield.”

Through the 1960s, the networks stubbornly looked away from the simultaneous earthquakes disrupting American life: the civil-rights and antiwar movements, the nightly carnage of Vietnam, the rise of the drug culture, the sexual revolution, and the feminist awakening. Instead, they mostly offered viewers a gauzy, pastoral vision of America.

With only three networks, shows needed to attract enormous viewership to survive. The prevailing aim at the networks and the advertising agencies was to produce what became known as “the least objectionable program” that could draw the most diverse viewership. In practice, this translated into shows that would be acceptable not only to urban sophisticates but also to small-town traditionalists. So, off the CBS assembly line flowed a procession of banal comedies celebrating the simple wisdom of rural life, including The Beverly Hillbillies and The Andy Griffith Show. Surrounding them were variety shows and comedies led by aging figures from the ’50s and even earlier, such as Ed Sullivan and Lucille Ball. Each night, CBS chronicled the tumultuous strains tearing at America on Walter Cronkite’s newscast and then spent the next three and a half hours of prime time trying to erase them from viewers’ minds.

CBS’s first attempt to reflect the changing culture came in 1967, when it premiered The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour. The Smothers Brothers, Tom the leader and Dick the straight man, were a modestly successful duo who had built an audience through albums and a nightclub act that combined stand-up comedy with gentle parodies of folk music. Their show was a hit from the outset and quickly became the one spot on television that seemed conscious of the burgeoning youth culture. Cutting-edge bands such as Buffalo Springfield, the Byrds, The Who, and Simon and Garfunkel all appeared.

As the show’s audience grew, Tom Smothers in particular became determined to use the platform to deliver a distinctly liberal message about contemporary issues, especially the Vietnam War. Tom said, “There’s no point of being on television … at this point in time, with what’s going on in this country, and not reflect what’s going on,” recalled Rob Reiner, the future All in the Family star, who joined the show for part of its final season as a writer. CBS censors predictably recoiled, snipping lines from some segments and rejecting others completely. The show had supporters inside CBS, but the network’s senior leadership grew weary of the constant arguments. Wood canceled the show in early April 1969, less than two months after he’d assumed the network’s presidency.

The cancellation underscored the difficulty of changing CBS. But pressure for a new approach was building, and it came, surprisingly, from the network’s business staff. CBS had the biggest audiences, but ABC and NBC were successfully wooing advertisers with their arguments that they had better audiences: young, affluent consumers in urban centers. “It was the sales department that said if we want to be competitive, we ought to try to get a younger profile with our audience,” said Gene Jankowski, a CBS ad executive who later became the network’s president.

Wood had not been elevated to the presidency with a mission to transform the network. He arrived with no announced mandate or vision; nor did he hope to leave his mark on the culture. He didn’t talk about the network as a public trust; he saw it, unsentimentally, mostly as a vehicle to sell soap and cars. Michael Ovitz, then a young agent, recalled that no one in the creative community looked to Wood for insight. “He never read a script,” Ovitz said. “And if he did, no one cared what he had to say about it.” Neither did Wood feel any urge to provide a platform for the new voices and social movements agitating for change: Even after he moved to more liberal New York City, his politics remained anchored well right of center. Irwin Segelstein, a top CBS programming executive, later said of Wood, “Bob is really Archie Bunker. The radical-right Irish conservative.”

But the advertising department found Wood receptive to its arguments for a new direction. One day in February 1970, Wood came to the sales department and said that CBS had to get younger in its programming and its audience. Privately, he told CBS executives that he feared losing the younger generation to the edgy new movies emerging from Hollywood, like Easy Rider. “A certain genre of films were pulling young people away,” Wood said later. “I sensed a shift in the national mood.” Wood knew he needed a program that would make a loud statement in order to attract new viewers. He “wanted to get some show that would cause some conversation,” recalled Perry Lafferty, the former director and producer serving as CBS’s vice president for programming in Hollywood. Norman Lear, during the first two decades of his show-business career, had displayed neither much interest nor much facility in generating conversation, but Lear would provide Wood exactly what he was looking for, and then some.

All in the family began as a British television show titled Till Death Us Do Part, the story of a working-class bigot, his sharp-tongued wife, their daughter, and her husband. It caused a sensation in Britain for its frank treatment of racism and other previously taboo topics, and its potential as a template for an American show seemed obvious. But when CBS tried to acquire the American rights to Till Death, it discovered that they had already been sold to Norman Lear.

The material had instantly detonated with Lear: The battles between the bigoted father and the liberal son-in-law reminded him of his own struggles with his father, Herman. In late summer 1968, he acquired the rights to the project and secured a contract from ABC to develop a pilot.

Lear did not begin adapting Till Death with any ambition to transform television. “I have never, ever remembered thinking, Oh, we’re doing something outlandish, riotously different,” he recalled. “I wasn’t on any mission. And I don’t think I knew I was breaking such ground. I didn’t watch Petticoat Junction, for Chrissake. I didn’t watch Beverly Hillbillies. I didn’t know what I was doing.” To the extent that he had an ulterior motive, it was more financial than artistic: Lear was attracted to owning a situation comedy that would provide a lasting stream of revenue if it were syndicated for reruns.

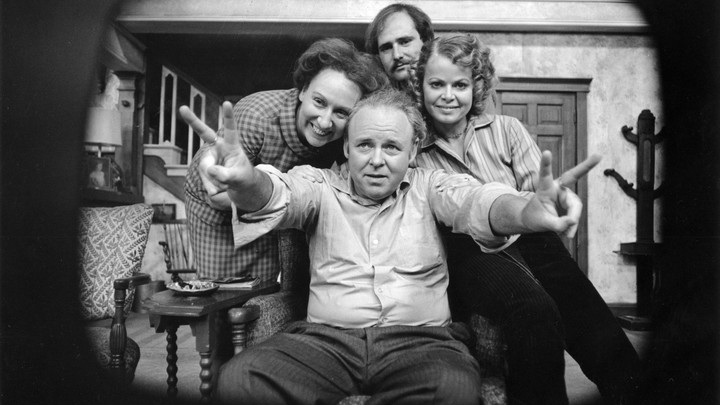

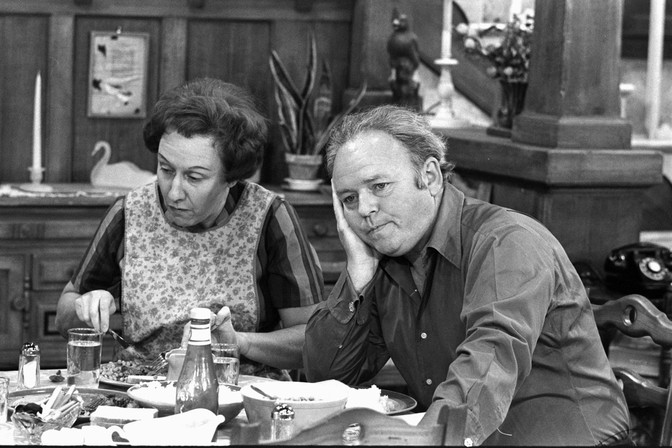

Lear moved quickly to write, cast, and film a pilot for the show, which he initially called Justice for All. He relocated the setting from London to Queens. For Archie and Edith, he chose Carroll O’Connor and Jean Stapleton. Neither was a household name, but both had worked steadily: O’Connor had been a character actor in dozens of movies and television shows through the ’60s, and Stapleton had worked on Broadway and in television. Lear cast two lesser-known younger actors as Mike and Gloria, and shot a pilot in late September 1968. ABC, however, rejected it—as well as a second, redo pilot he shot a year later.

Lear’s agent pushed the concept to CBS. Wood was initially hesitant, but soon recognized that he had found his conversation starter. He later explained his thinking to the sociologist Todd Gitlin: “I really thought the pilot was very, very funny … It sure seemed to me a terrific way to test this whole attitude about the network.” Just a year after Wood buried the Smothers Brothers, he gave new life to Archie Bunker.

Even with Wood’s support, the show faced formidable headwinds within CBS. William Paley, the autocratic chairman of the board, hated it from the outset, considering it vulgar. But Wood was determined. “Bob Wood had balls,” said James Rosenfield, an ad salesman at the time who went on to become the president of CBS. “He really had balls, and what I never understood to this day was how that happened, because Bob Wood came out of sales. He didn’t have any clout with the Hollywood community. He didn’t know Norman Lear, but he understood that there was an opportunity here for significant change in the medium, and he made it happen.”

With the go-ahead from CBS, Lear reshaped the cast with new choices for the younger roles. For Gloria, the Bunkers’ daughter, he chose Sally Struthers, a young blonde whom Lear had seen on the Smothers Brothers and in the movie Five Easy Pieces. For Mike, the son-in-law, Lear looked closer to home, casting Rob Reiner, the son of his longtime friend Carl Reiner. In addition to his writing for the Smothers Brothers, the younger Reiner, with long hair and unabashedly liberal views, had become the go-to casting pick for the industry’s stilted first attempts to acknowledge the changing youth culture, on individual episodes of The Beverly Hillbillies and Gomer Pyle. “I was like the resident Hollywood hippie,” Reiner said later.

For the director, Lear chose John Rich, a skilled television veteran whom he had met two decades earlier. Coincidentally, Rich had been approached at almost exactly the same time to direct The Mary Tyler Moore Show, which preceded All in the Family on the air at CBS by four months. While Mary was pathbreaking in its own, quieter way—illustrating the changing roles of women in American society through deft and affectionate character studies—to Rich the show didn’t appear nearly as revolutionary as Lear’s project. “It was 1970, and the dialogue that was written then just blew me away,” Rich remembered. “And I called Norman … I said, ‘You aren’t going to make this, are you?’ He said, ‘Yeah.’ I said, ‘Is anybody going to put it on?’ He said, ‘They say they will.’”

Rich’s uncertainty, even incredulity, was widely shared. Even with CBS’s approval, the show’s future always seemed tenuous to the cast and crew as they worked toward their January 1971 premiere. “We knew we were doing something good, but we didn’t think anybody was going to go for this,” Reiner remembered. O’Connor was so skeptical that the show would survive that he held on to the lease for the apartment in Rome where he had been living and made Lear promise to pay for a first-class ticket back if the show was canceled.

Lear, too, felt that CBS’s commitment was only conditional. Yes, Wood had bought the show, but he remained skittish about it. “He wanted to take a chance, but he fought me tooth and nail,” Lear remembered. Wood and CBS were simply uncertain that a show this different from their usual programming would find an audience. “That’s all they worried about,” Lear said. “It’s as simple as ‘We don’t know if this works.’ We know the Hillbillies and Petticoat Junction—we know that works. We don’t know if this works.” During the filming of an early episode, Rich was in the control room when Wood stopped by the set. “I hope you know what you’re doing,” he told the director, “because my rump is on the line here.” Just weeks before the show was scheduled to air, CBS still had failed to sell any advertising to air with it.

From the start, Lear participated in an unrelenting push and pull with the CBS censors over the show’s language and content. The network’s caution was evident in the time slot it selected for the show: Tuesday, a night it didn’t view as pivotal, at 9:30 p.m., between Hee Haw and the CBS News Hour. In advance of the premiere, Wood sent a telegram to CBS affiliates quoting a speech he’d delivered the previous spring: “We have to broaden our base,” he wrote. “We have to attract new viewers. We’re going to operate on the theory that it is better to try something new than not to try it and wonder what would have happened if we had.”

CBS even developed an unusual disclaimer to appear just before the show’s first episode, explaining that All in the Family “seeks to throw a humorous spotlight on our frailties, prejudices, and concerns. By making them a source of laughter, we hope to show—in a mature fashion—just how absurd they are.” To the cast, the disclaimer “was ridiculous, because they’re putting the show on the air, and yet they’re trying to distance themselves from the show at the same time,” Reiner remembered.

CBS’s ambivalence crystallized into a single choice: which episode to air first. Lear wanted to start with the third version of the pilot, which he had taped with the new cast. Viewed even decades later, the episode is explosive. Summoning painful memories, viscerally connected to his characters, Lear, then in his mid-40s, found in his script a passionate and urgent voice he had never before tapped. Within minutes, Archie is raging against “your spics and your spades”; complaining about “Hebes” and “Black beauties”; calling Edith a “silly dingbat” and telling her to “stifle” herself; and describing Mike as a “dumb Polack” and “the laziest white man I’ve ever seen”—the latter a reprise of an insult that Herman Lear used to direct at his son. Mike, just as heatedly, is blaming crime on poverty and insisting that he and Gloria see no evidence that God exists. In the opening scene, Archie and Edith arrive home early from church and catch Mike kissing Gloria amorously as he carries her toward the bedroom. Archie is scandalized: “11:10 on a Sunday morning,” he grumbles in his thick Queens patois.

This was all a bit much for CBS, especially the “Sunday morning” line—which clearly suggested that the young couple was on their way to have sex (during daylight, no less). The network insisted that Lear take it out; he refused. Wood offered a compromise: The line could stay in if Lear agreed to push the pilot episode back to the second week and run the projected second show first. Lear refused again. He believed the pilot episode presented “Archie in full,” with all his prejudices and animosities on open display. Airing it was like jumping into the deep end of a pool; CBS and Lear together would “get fully wet the first time out,” as Lear later described it. In what would become a common occurrence, Lear told Wood he would quit if CBS started with the second episode.

On January 12, 1971, the date that All in the Family was scheduled to appear for the first time, Rich and the crew were performing a dress rehearsal for the season’s sixth episode in the CBS complex known as Television City, at Beverly Boulevard and Fairfax Avenue in Los Angeles. Just before 6:30 California time, they crowded into Rich’s small control room, where they could watch a network feed as the show’s 9:30 eastern airtime approached. They might have caught the final minutes of Hee Haw, a last vestige of television’s obsession with rural audiences, before the control room filled with the disembodied voice reading CBS’s strange disclaimer. Then came the sounds of Jean Stapleton at the piano as she and Carroll O’Connor sang the show’s nostalgic theme song, “Those Were the Days.” Still, it wasn’t clear yet which episode CBS had placed on the air. Within moments came the image of Mike pursuing Gloria in the kitchen and her parents arriving home early from church, the initial scenes of the pilot. The CBS eye had blinked. Television’s search for a new audience had finally torn down the curtain separating it from the tumultuous changes unfolding around it. Through that opening would emerge some of the greatest television ever made.

======

No comments:

Post a Comment