When the Twitter account of its own chief executive, Jack Dorsey, was taken over by hackers last year, a stream of tweets with racial slurs, profanity and praise for Adolf Hitler were posted for 30 minutes. Weeks later, the food writer and campaigner Jack Monroe lost £5,000 from bank and payment accounts accessed from a hijacked phone.

Both were victims of “sim-swap” fraud, a scam that has mushroomed in the last few years and has led to victims losing thousands, often before they even know anything is amiss. Fraudsters take control of a mobile phone account through a mixture of confidence tricks and online stalking, and then use those details to get access to the owner’s bank accounts.

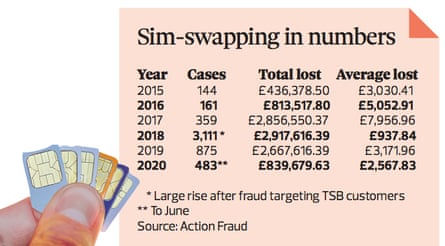

Figures from Action Fraud, the national fraud reporting centre, show the number of people falling victim to this type of scam has increased substantially since 2015 and that it has resulted in losses of more than £10m to UK consumers. So how can you ensure that your phone, and therefore your bank details, are safe?

The scam

Variously called sim splitting, simjacking, sim hijacking and port-out scamming, the fraud focuses on moving control of someone’s phone account from their sim card to one controlled by the criminal.

“The tactic hasn’t changed significantly over the years,” says David Emm of cybersecurity firm Kaspersky. “The criminals obtain a victim’s personal information – bank details, address, etc – by trawling through social networks or by mining data stolen during the breach of an online company’s systems. They then contact the victim’s mobile phone provider, pretend to be the victim, request a sim swap and change personal settings.”

Emm says that in some cases fraudsters work with an insider to assign the victim’s number to another sim. “One, more recent, tactic is to request a porting authorisation code [PAC] to port the victim’s number to a different network,” he says. “Once they ‘own’ the victim’s number, they are able to intercept bank authorisations sent via SMS – or other … codes that the mobile number is used for.”

Often the fraudster will use information that has been put up on social networks, such as a mother’s maiden name, a birthday or the name of a pet, to help build up an information base on the victim.

Last week we featured an Observer reader whose number was stolen by a criminal who used the reader’s identity to request a PAC to transfer it to the criminal’s phone. Payments of more than £1,000 were then made from the victim’s bank account to an online money transfer service.

Last year the FBI warned of the risks of sim-swapping, saying it was a common tactic to get around security measures such as two-factor authentication, where users have to give two pieces of information, such as a password and a code sent to their phone. This warning prompted the UK’s National Fraud Intelligence Bureau to also raise concerns. The FBI wants more complex forms of authentication to be introduced.

How to know you have been scammed?

Usually someone first becomes aware that they have fallen victim to a sim-swap scam when their phone stops working or they discover they are unable to access bank and credit card accounts. Or they may get a text message or an email prior to the swap taking place.

“It’s vital, if that happens, to contact the mobile network provider and inform them, so that they can investigate what has happened,” says Emm. “It’s also vital to contact the bank, or other online services where you use your mobile as an additional form of authorisation for transactions.”

NatWest’s head of fraud prevention, Jason Costain, says: “Banks take measures to defend against sim-swap. However, our industry, like many others, relies upon the telephone companies to ensure adequate ID checks are performed before a sim-swap is permitted. The telephony sector is working to mitigate the threat.”

A spokesperson for the Financial Ombudsman Service said that when money is fraudulently taken from someone’s account they should contact their bank, where it should be deemed a “disputed transaction”. It is then up to the bank to investigate and decide whether it will pay back the money. If it doesn’t, the customer can go to the ombudsman.

“If a consumer is unhappy with the outcome, they should get in touch with our service and we’ll see if we can help,” said the spokesperson. “We’ll make our decision about what happened using evidence provided by the consumer, the bank and any relevant third parties. In reaching a decision, we’ll consider relevant laws, any regulations that applied at the time, any industry codes of conduct in force at the time and the terms and conditions of the account that the disputed transaction was made from.”

Avoiding the problem

As with many frauds around bank security, there are simple ways for consumers to avoid being scammed:

Don’t respond to unsolicited emails, texts or phone calls. These may allow attackers to access personal data which can then be used to convince the bank that they are you.

Don’t overshare personal details on social networks. Avoid putting your birth date, that of children or relatives, the name of your first pet or school, as these are all frequently used as the answers to questions that banks ask.

If your phone stops working normally, inform both your bank and your mobile phone provider.

Try and use an app such as Google Authenticator for one-time passcodes.

Use passwords that only you will know and which are unique.

No comments:

Post a Comment