Changing the narrative of hospital circumcision shame

Others, though, are devastated. They may be eligible to attend, but missing classes, in anguish over what’s happened to their bodies. Some may even be suicidal.

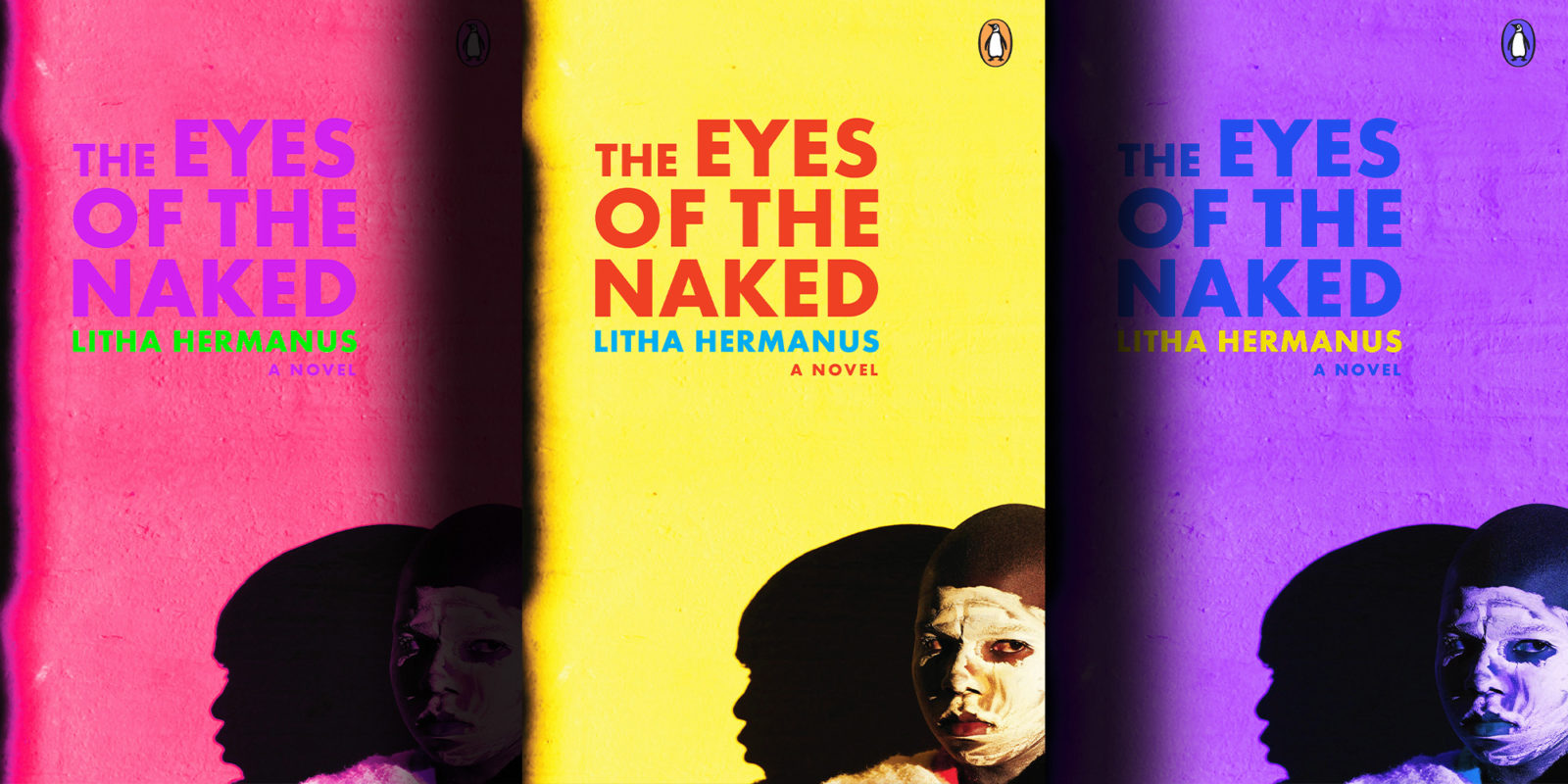

These maimed young boys may be faceless to most South Africans, but I’ve seen inside the eyes of one. Their dismal sense of loss remains with me to this day. Along with my own angst around traditional Xhosa manhood, I came to write about it in The Eyes of the Naked(Penguin/Random House):

The boy was being attended by a medical doctor. A permanent grimace was on his face. He swayed his head side to side, his body failing to hold back shudders, in the manner of one managing extreme pain.

Like the rest of us, he was naked under a white blanket. But his was held open. As I passed close to him, I understood why his face signalled more agony than should’ve been present with the loss of a foreskin. He’d lost more than that. What was left was like a sausage on a flaming grill, the meat inside it swollen and ready to split open its casing. The member was gangrened; soon to be amputated.

The look in the boy’s eyes can be best described as a desperate, voiceless cry. Someone he trusted had thrown his life off a high cliff, and he didn’t know how he’d ever stop himself from falling. All seemed over but death.

****

I was 18 years old when I got the cut. The custom isn’t something I’d sought with enthusiasm. While it was expected, it wasn’t considered of utmost importance in my family.

Also, my best friends of many years (two white brothers and a Ghanaian boy), had no relationship with it. They’d ask why I had to do it if my family weren’t faithful traditionalists.

I lived within a Xhosa community and had other friends, was the answer. They, and other peers, would interrogate me about it if I went through life without umgidi (a post-circumcision ceremony). Ask Fikile Mbalula. He was 37 years old when his peers forced him to “fix” the pout in his pants.Besides, my father had done it. And I had two older brothers. The eldest was enthralled with the idea. Because he was a pre-marital child, he was raised by our grandmother in the rural Transkei until high school. So his ideas around manhood were formed on what one might call culturally rich ground.

Still, the cut was not something discussed much at our house.

I would come to find out that even in my father’s own youth it was downplayed. Unlike when he was younger though, something changed. The men with whom he worked and socialised by the time I came of age were conscientious with their customs. As we approached my date, fights ensued between my parents regarding the event.

My father was baying for traditional blood. Over my mother’s dead body!

This was in 1994, before the many reforms that would be introduced to the custom. A time when botched jobs existed, as they do now, but alongside rampant HIV infection, in the deadlier days of the disease.

In many ways, my mother was more present than my father as a parent. Perhaps this made her comfortable with her demands, even though the opinion of women is forbidden in this arena. After many disagreements, my dad conceded. I would use a hospital and move on to the appropriate setting.

Fortunately, a relative had farmland. I was allowed to use a mud-and-thatch hovel on his farm along with two other initiates. It wasn’t “the mountain”, or a glade in some forest, but its redeeming factor was precisely in that it wasn’t a backroom from where I could hear my own mother.

Still, this was not the age-old way of erecting one’s own grass-dwelling, and burning it down when emerging as a “man”. These things mattered.

****

And so it is that my experience with traditional manhood is knotted with angst. And not for nothing… Over and above the choices made by my parents I have my own indiscretions.

In certain contexts, my status renders me a boy: a persona-non-grata – a dog. (Woof!)

Firstly, my attacker was a childhood friend. I still considered him one; certainly not a foe. Yet, when we encountered each other for the first time after our respective hibernations, he lashed out in a vitriolic way. But there were mutual friends about. They made sure the incident didn’t escalate beyond words. I would have gladly cleaned the Holiday Inn parking lot with his smirk. It didn’t matter though; he’d already won. The source of our public disagreement was rooted in my “shame”.

But even odder than being attacked by a one-time friend was the following:

While my accuser was a “mountain man”, two of the guys with him weren’t. We’d seen each other at the hospital on a couple of occasions. This was either for the cut or during check-ups. Yet, their friend didn’t know their secret. And it wasn’t my place to expose them.

I’d soon find out how much pressure was felt by Xhosa initiates around this issue. Lying about the authenticity of one’s circumcision experience is more common than you might think. It’s a viable (though precarious) way of mitigating the backlash of humiliation, violence, or being ostracised.

Generally speaking, all boys want to become men the “real” way. However, for most, it’s parents who decide which side of the blade their manhoods will fall on – the side of “the spear” or that of “the scalpel”. Parents should be duty-bound to the lives of their children, before they are servants to culture. Their decisions should hinge highly on the state of safety evident or lacking within the ritual.

****

For his own part, my father understood the trials and tribulations of living among traditionally solidified men with litanies of clan names, while being something far from that. I’m more concerned with the project of personal decolonisation. I’ve come to find moral decrepitude in being in a cultural wilderness and doing nothing about it.

Had I the power to relive the custom, would I make different choices from the ones made by my parents? Yes! But, while on the side of the “authentic” cultural experience lies the glory, the way to it is paved with the scariest possibilities of disfigurement and death. Surely both are worse than “shame”.

I’ve often vacillated between absorbing and disregarding my so-called shame. But I’ve come to dismiss it because the memory of the gangrened initiate has allowed me to do so, more and more over time. The following is no small realisation:

My parents were right in their choice to protect me. The mutilated boy I saw that day could easily have been me. I should think in the very same way regarding my son.

****

Things have improved though. My gangrened initiate faced his tragedy 20 years before Prof Van der Merwe’s team at Tygerberg Academic Hospital were successful with the inaugural penis transplant. Still, sane minds would favour a rise in safer traditional circumcisions than in transplants.

Another improvement is that since 2005, male circumcision for those under 18 has been regulated by the Children’s Act. It’s a protective framework for under-18 boys and even those under 16. Medics are also sent to check on the health of the boys in licenced schools, in order to mitigate hazards.

Some schools, though, evade the law. In the past, Prince Mahlangu – member of the CRL Rights Commission – has suggested that out of all existing schools, only 2% are problematic. Is it honestly this number that’s responsible for the epidemic of approximately 300 amputations and 8,000 hospital admissions over the last 12 to 13 years, according to the Medical Brief?

In 2018, it was reported that Nelisile Nongqa’s sons in Gabazi (Eastern Cape) were attacked in their sequestered state as initiates, because one of them had previously tried his circumcision at a hospital. He was brutally beaten, on his newly circumcised member, and all over his body. The irony? He was punished for doing a manly thing: righting a previous wrong, and this was reportedly at a legal school.

In the last two months, over 20 deaths were recorded during the recent initiation season. The CRL Rights Commission even called for the immediate suspension of certain schools in the Eastern Cape. Fact: schools may only be “suspended” if they’re licenced. The two examples above beg the question: Should one feel safe simply because a school is considered legal? No!

Another question: Is there a way of keeping this process traditional while lessening the degree of danger? There are many thoughts out on this, but here are mine:

Manhood needs to be redefined and codified if we are to continue doing this, without being accomplices to injustice. Manhood needs to be intentionally imbued with timeless values, but also a strong sense of what it means to be a man in today’s local and global world, in utilitarian and progressive ways. The institution hinges on much more than one’s activity over four weeks of hibernation in the bush.

And let no MAN continue to feel bad for going to the hospital. The custodians of the culture are the reason our parents sent us there. By feeling humiliated for going to the hospital we allow ourselves to be taken hostage for decisions that were not ours to make. Furthermore, we allow ourselves to be taken hostage by those who cause the conditions that compel our parents to send us to hospitals in the first place.

Let’s rise up with purpose and show that manhood is deeper than a cut. Do not be me! By feeling humiliated by my accuser all those years ago in a Holiday Inn parking lot, I did something I should never have done. I allowed myself to hear the logic of a lion in the bleating of a sheep. DM

Litha Hermanus is the author of The Eyes of the Naked – a political and psychological novel, published by Penguin Random House. Follow him on Twitter @Lithahermanus

No comments:

Post a Comment