AS ALWAYS, Steve-O is the punchline. The 47-year-old begins his touring comedy show The Bucket List with a joke highlighting the unlikelihood of his being here to deliver it. He didn’t die jumping off a balcony and lying unconscious in a pool of his own blood trying to impress a woman as a young “attention whore”—his accurate term, with which he liberally seasons his continuous “diatribes” (also his accurate term). Steve-O did not perish getting sepsis from stapling his scrotum to his thigh for his Don’t Try This at Home video or blowing himself up by shooting fireworks out of his ass on Jackass or inhaling 600 canisters of nitrous oxide a day—and filming the whole thing—during a period of drug use so prolific he spent his time communing with hallucinated friends inside his apartment and sending hostile email missives to a group of corporeal friends he rarely saw and who in 2008 had him involuntarily committed to a psych ward after he informed the entire “Rad Email List” that he was planning to throw himself out of his third-floor bedroom window.

“Most people would be delighted to hear that they’re actually not going to die in their early 30s,” Steve-O says now, almost 14 years into the sobriety wrested from what he believes is a familial predisposition to addiction. “It came to me as a crisis. I was confronted with the most terrifying possibility: I was only like halfway through my life.” He had little money and no idea how to make more, having alienated his personal and professional connections and seeming to possess few skills beyond inspiring people to shout, “Oh shit, it’s Steve-O!” when they saw him. “The ultimate fear for me would be to be a recognizable personality and totally broke,” he says.

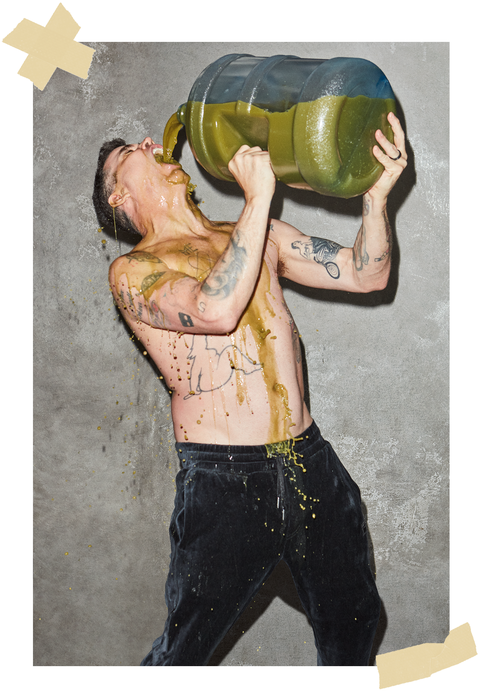

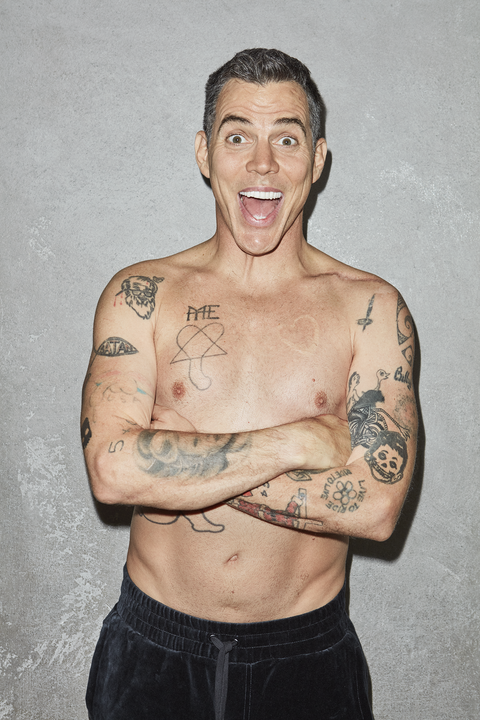

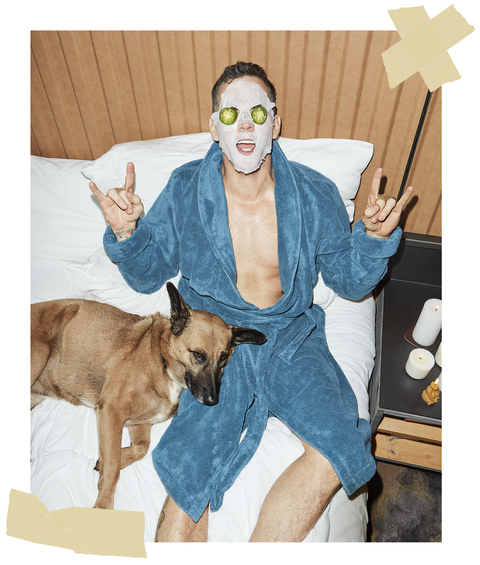

But in a series of events as improbable as surviving his attempts to destroy himself for our entertainment, Steve-O transformed himself into someone who is a credible model of men’s health. After taking the novel steps of “changing my lifestyle and actually taking care of myself and being concerned with my health,” he began doing stand-up, mainly comprising compellingly self-deprecating stories about stunts he then shows video of. He wrote a 2011 memoir called Professional Idiot, which sold more than 170,000 copies and is revealing even for someone whose rectum we have become acquainted with. Its follow-up is a self-help book, which will be published this September.

Steve-O has since appeared in the Jackass movie Jackass 3D and stars in this month’s Jackass Forever. He began a podcast and a hot-sauce line and a merch fulfillment center that works with Tony Hawk. He stopped eating meat for animal-welfare reasons and became engaged to stylist and designer Lux Wright, who has both appropriate boundaries and a stomach that allows her to unflinchingly hold a camera and film Steve-O shitting into a box fan. He has traded in fuck-your-knees Vans for a style of white Asics you could describe only as “tennis sneakers” and moves nimbly for a man who has inflicted so much bodily trauma on himself, evident only in the slight quiver of his hands as he texts Tommy Lee to let him know he’s wearing a Mötley Crüe T-shirt for his interview. Only a vestigial I remains of the shit fuck tattoos he had lasered off the traditional love hate positions on his fingers.

So despite the joke, being Steve-O in his 40s is actually quite a nice position. “But if I go out there and say, ‘I’m in a terrible position. I’m Steve-O in my 50s . . .’ ” he says with clear concern, “I think that’s a considerably less funny joke.

“Maybe the more I grow, maybe I just want to get out,” he says. Then Steve-O identifies the problem with escaping himself: “I don’t know how to get out.”

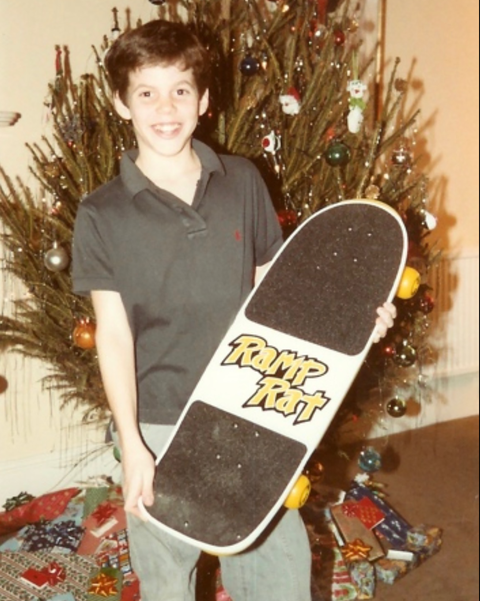

BEFORE TAKING ON the role of Steve-O, he was Stephen Glover. In sixth grade, Glover’s teacher wrote something on his report card that would both explain and inform this transformation. “Socially, Steve’s attempt to impress his peers frequently has had the opposite effect,” it read. His (often literally) naked pleas for attention mostly involved self-harm: making himself bleed, setting himself on fire. Glover would do anything and do it on camera, with hopes that others would be interested enough to watch, which made him problematically useful in the punk-stunt subculture he wound up on the periphery of. After dropping out of the University of Miami, he balanced his desperation to be seen, even with derision, with a desire for legitimacy; he enrolled in the elite Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey clown school in 1997. But a true vessel didn’t exist until Jeff Tremaine, editor of the skateboarding magazine Big Brother, partnered with Johnny Knoxville and future Oscar winner Spike Jonze to create Jackass for MTV.

The prank and stunt series premiered in 2000 and was a tremendous hit, begetting six spin-offs and four films, the first three of which collectively grossed $336 million. The Joe Rogan–led Fear Factor followed less than a year later, and Ridiculousness, the illegitimate child of Jackass and America’s Funniest Home Videos, now airs in virtually every time slot on MTV. Erin Buckels, a professor of psychology at the University of Winnipeg, says of these shows’ popularity, “There’s something primal in seeing people get hurt. It’s arousing. And that could be a negative or positive experience.”

Buckels uses the term “everyday sadism” for normal people who get pleasure out of others’ pain; she likens the impulse to laugh when the Jackass guys run through a hallway of Tasers dangling on strings—deemed “vicarious sadism,” versus gratification from inflicting suffering—to the excitement some get from pornography. (Glover, who went to rehab for sex addiction after getting sober, doesn’t watch porn because he believes it’s detrimental to relationships.) Either way, you like what you like, and then your brain comes up with excuses for why it’s okay. Glover chose to do this. He was having fun with his buddies. He was making money off it, starting with $1,500 for the first season of Jackass—paltry, but still significantly more than he had been earning selling drugs in the parking lot of Grateful Dead concerts. “We make sure that you don’t have to feel bad about your everyday sadism, because we’re inviting you to enjoy it,” Glover says after learning of the concept. “So it’s completely permissible to enjoy it, because it’s understood that the reward is your attention; you’re actually being generous when you enjoy it.” In other words, you’re allowing the Jackass cast to have careers.

One other justification an audience might have for being amused by the pain inflicted upon the Jackass guys is that these people deserve to be punished for the qualities that have made them famous. Bam Margera is cocky and torments his parents; Knoxville is the sicko who put this thing together; and Glover is Steve-O, the man whose less egregious acts of spotlight chasing include getting his own face tattooed on his back. “It’s schadenfreude,” Buckels says. “We like to see deserving, high-powered people get hurt. And if they have a certain persona that’s almost antisocial, maybe that does help us release any kind of hesitance we have to laughing at that.” Part of the brilliance of Jackass was the cycle it created: The shittier the cast acted, the more celebrity and money they gained from that shittiness, and the more fun we had watching them treat themselves like shit.

But as Glover became more well-known, his behavior—and substance use—went from bad to unbearable. He began urinating on red carpets and terrorizing his neighbor. He recorded a hardcore comedy-rap album, which inspired him to try, and repeatedly fail, to get arrested. Cops would recognize him and let him go. Was it not a crime that Steve-O had drugs on him, or was it simply a benefit of being a famous white guy?

Glover denies this was some grand design. “I don’t know about cultivating douchiness to make it permissible for [audiences],” he says, allowing “perhaps that was part of my subconscious.” He has another theory: “Maybe it was that I had some kind of low self-esteem or something, and I felt like I deserved that.” He often felt as though his Jackass costars were superior to him. “These guys just had this charisma on camera, and they could make anything funny without risking their bodies or making some huge thing. [Chris] Pontius is that way. He’s just a genius. For them it came more natural; they’re just talented. I feel like to get footage and to get screen time, I always had to work harder.”

Knoxville led the team of people who, physically and very much against his will, forced Glover into rehab. The process of getting sober through Alcoholics Anonymous involves moving the focus away from your own fears and grievances and excuses and onto your impact on others. (Glover forgoes the Anonymous part because Steve-O doesn’t do anything anonymously.) “The fourth step is an inventory, where we go through our resentments,” he says. “It’s pretty clever the way it’s designed, because it’s really easy to start out making a ‘fuck you’ list. ‘Fuck this person! This person fucked me!’ So I did that, and then when I sat down with the inventory, what was so crazy is that I had written down a list of people I treated horribly. And I’m talking about how I’m mad at them. Recovery is so much contingent upon smashing the ego. And a career in attention seeking . . . like, it [seemed as if it] wouldn’t even work.”

Still, when Glover was invited to be part of Jackass 3D in 2010, fresh out of a halfway house, he said yes. “I was afraid,” he says. “I was exposed. I was super uncomfortable.” In that film, he appears to be physically recoiling even when not being shaken inside a bungee-cord-powered, feces-filled portable bathroom. He hides behind the cast he feels inferior to, smiling nervously and silently because he’s too afraid to throw out jokes and have them not land without the cushion of intoxication. One of his costars, Ryan Dunn, would die in a drunk-driving accident a year later.

With Jackass Forever, Glover felt secure in what he could bring to the film. He’d spent a decade touring—“My comedy career has been considerably more lucrative for me than my Jackass career,” he says—and accruing the most social-media followers of any of the castmates, including Knoxville. With the producers feeling like Margera couldn’t safely take part, Glover is the indisputable second lead of the film. So he went to Knoxville, Jonze, and Tremaine and asked for an amount of compensation commensurate with what he calculated to be his worth.

Glover eventually got a producer credit. But he did not get a dollar more than Dickhouse Productions initially offered him. He claims he’s fine with it. The film is great, he projects as much onscreen charisma and confidence as one could ever imagine from a man whose testicles are being stung by bees, and, he says, “the fact is that I have multiple other revenue streams, which all benefit [from Jackass]. So I would have been cutting my nose off to spite my face if I wasn’t in the movie because I didn’t get the deal I wanted.”

It also would have meant cutting ties with Knoxville, whom Glover says he admires like no one except his own father and praises as reflexively as someone else might spit to ward off the evil eye. Knoxville calls while we walk through Washington, D. C., looking for a preshow Covid-vaccine booster with Wendy, the stoic service dog trained to help with Glover’s psychiatric and mobility issues. (Besides his exact Jackass film earnings, the precise conditions that require Wendy’s service are the only topic Glover declines to further discuss.) He immediately puts Knoxville on speakerphone.

“Cap!” Glover says. “Dude, you’re on the record right now because I’m being followed around by Men’s Health magazine for my feature article.”

I ask Knoxville if he’s ever had a conversation with Glover that wasn’t documented.

“Well, you never know what you’re going to get when you call Steve-O,” Knoxville says in his bemused drawl. “Usually, you’re going to be on record. There’s some kind of filming going on. There’s always some type of shenanigans, but he always is very up-front about letting you know.”

Glover confesses we’d just been talking about him: “I said, ‘I don’t fucking like Knoxville getting in front of bulls. I totally worry about his brain.’ And then I said, ‘My dad is 78 years old, and I pay such close attention to every correspondence and every conversation because I’m so terrified of Dad not being so sharp anymore and any kind of dementia creeping in. It’s tragic as fuck to say, but I do the same thing with Knoxville, you know? Looking at his texts, talking on the phone, whenever we’re hanging out, just [wondering], Has the brain trauma fucked up the captain?’”

Knoxville seems less than thrilled that Glover is speculating about his potential cognitive decline to a national magazine. “Well, that’s very sweet, Steve-O,” he says. “But unlike your father, I was never that sharp to begin with; otherwise I wouldn’t be doing what I’m doing for a living, okay?” He excuses himself from the conversation he didn’t sign up for and asks if Glover can call him back.

“I absolutely can,” Glover says, beaming his giant veneers at the phone. “And bravo, brave captain, for putting yourself down, and in the same stroke proving that you are, indeed, so fucking sharp and my concerns are unwarranted.”

“Oh, yeah, sharp as a butter knife,” Knoxville says. “All right, well, I love you guys. I will speak to you later.”

“Love you, Knox,” Glover says.

Later, Glover will tell me, “I know that it’s counterintuitive to describe Jackass as something that’s wholesome, but I feel strongly that it is. . . . There’s just nothing mean or dark.” I trust him so deeply I almost forget that he parses his captain’s text messages looking for signs of CTE from the movies they make together.

“THIS WHOLE SHOW is all about existential panic, this race against the clock to do the most spectacularly dumb shit possible before it becomes creepy to watch,” Glover says of his Bucket List tour. “Knoxville believes that the older we get, the funnier it is”—that one day Bad Grandpa and the other prosthetics-enabled elderly characters featured in Jackass can just be the actual geriatric cast. Glover is “not so sure.”

With the meticulous dedication Glover once put into chronicling his self-destruction on video, he is constructing a miniature empire to escape to once he’s done with all this. The Wild Ride! podcast, YouTube videos with names like “My Ten Worst Stunt Injuries” and “Breaking Down Every Drug I Ever Did,” the merch distribution, plans for an animal-sanctuary eco-lodge and maybe a tattoo shop. “I’m not that great at giving tattoos, but I’m shockingly better than you would imagine,” he says. “And the reality is there’s pretty crazy demand for a shitty tattoo from Steve-O. I’m mindful about thinking of ways to support myself without being an attention whore.”

To get to this oasis, Glover has mapped out what he calls a “delusional vision.” First, Jackass director Tremaine will watch The Bucket List and agree to help him present it to Netflix, which will buy and distribute it, enabling Glover to play his next shows in arenas. “That felt grandiose and kind of crazy, but I can’t help it,” he says of dreaming aloud of something on that scale. His final outing will be the Gone Too Far tour and will feature, among other stunts, Glover receiving breast implants (“huge, hairy man titties,” as he says); getting a penis tattooed over his eyebrow; and having a bullet shot through his open jaw, which will cause comedy “purists” like Marc Maron to take him seriously as a stand-up. Then he will finally be free from the blessed trap of being Steve-O: generating enough attention to fulfill his primal need but in a way that keeps him from garnering the esteem he truly craves. It’s an issue he was conscious of before it ever came up; in an unpublished memoir he wrote while serving a ten-day sentence for a DUI in 1996, the unfamous 21-year-old neatly penciled, “They call me Steve-O. I’m thinking about switching back to Steve Glover, because now I’ve kind of begun a career and I don’t know if I want a nickname when I’m famous.”

When I gently point out that his way out of seeking attention is to get the attention of a major entertainment corporation, the top tier of stand-up comedians, and an entirely new and much larger audience, Glover takes it in. “I agree,” he says. “There’s something inherently paradoxical about my pitch.”

Wright, Glover’s fiancée, says she told him, “You’ve already proven your worth in the entertainment industry. Your work isn’t corporate driven, so it’s not surprising if it doesn’t happen. At the same time, you don’t need them. You don’t need validation from anybody. You and all the Jackass guys did this thing: You created this genre that nobody else had ever done. And because you guys created it, you are that legacy. That’s never going to change.” (Wright also told me Glover will not be shooting a gun into his mouth.)

Glover calls me a few days after our time in D. C. to clarify the plan. “I imagine a time, say, five years down the road, where I’ve done my thing,” he says. “I’ve now had my fake boobs and then gotten them removed. I’ve had the dick on my forehead, and I’ve gotten it lasered off. I’ve gone back to my current status quo: a deteriorated guy pushing 50 years old. And maybe it all worked out the way I thought; maybe I really hit that big home run I was looking for. Then I’m in a position of saying, ‘Okay, do I really want to keep trying to raise the bar?’ ” Though no accomplishment has ever satiated him in the past, he thinks the answer will be no.

While we’re on the phone, I tell him I got in touch with his sixth-grade teacher, the one who’d come up with the assessment Glover has repeated so many times. The one who wrote the story Glover always tells about himself: “Socially, Steve’s attempt to impress his peers frequently has had the opposite effect.” I quoted the Mrs. Iacuessa of around 35 years ago to the present-day Mrs. Iacuessa. She was shocked. She wouldn’t have said that to a sixth grader! Besides, she’d adored Steve. “He was starting to decide who he was and what he wanted to be,” she said. “He had the biggest smile. He was a boy!” Then I reminded her of the second part of the report-card note, which Glover does not quote in interviews. “Perhaps if he had more empathy . . .” she wrote.

Mrs. Iacuessa responded that I should ask Glover about his father, a retired packaged-foods and tobacco executive who traveled with his family around the world and then left them in larger and larger homes as he went on longer and longer business trips. While he was away, Glover’s mother began saying she was sick and staying in her bedroom to get drunk, eventually telling the family she had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and that she was undergoing chemotherapy. It was a lie.

I asked Mrs. Iacuessa what specifically I should inquire about Glover’s dad, and she replied with one phrase: “his anger toward Steve as a young lad.”

I tell Glover what she said and posit a theory: What if the thing that had acted as something between a career blueprint and doomsday prophecy wasn’t ever meant to be either? What if Glover wasn’t even supposed to read the message? What if his teacher had been trying to help him by nudging Glover’s lone capable parent, a man whose absence created a black hole of need and who became angry when his son filled the emptiness by acting out to get attention?

“It’s kind of piercing to hear,” Glover says quietly. He pauses for his only break in speech in any of our interactions. “That’s pretty, pretty heavy.”

We talk a little more. About the book, about Glover’s father, whom he’s now close enough with to have him join in shooting fake semen out of multiple dildos at an effigy of Johnny Knoxville—the two men Glover fears losing the most, bound by a simulation of bukkake. Then Glover contemplates the kind of attention this article will bring. His publicist warned him, among other things, not to take his dick out in front of the Men’s Health photography team. “For all of the publicist’s concerns, like ‘Oh, be careful, you’re on the record, they’re always going to be super nice, and then they’re just gonna write . . . .’” He trails off, indicating all the unflattering potential stories one could tell about Steve-O. “And I was like, ‘Cool, man. Great. There’s absolutely nothing that I intend to try to hide.’” Glover isn’t ready to stop exposing himself just yet.

No comments:

Post a Comment