Texas Ranger James Holland became famous for cajoling killers into confessing to their crimes. But did some of his methods — from lying to suspects to having witnesses hypnotized — ensnare innocent people, too?

Roughly 24 hours before Larry Driskill confessed to a murder he claimed he couldn’t remember, a stranger in sharply creased cowboy clothes approached him at the barn where he was working. The metal star above the man’s left shirt pocket indicated he was a Texas Ranger.

“Am I in trouble or what?” Driskill asked.

“No, we think you might be able to help us,” Ranger James Holland replied, inviting Driskill to chat at the sheriff’s office in Parker County, Texas. As they cruised the rural back roads west of Fort Worth on that afternoon in January 2015, Holland made small talk, drawing out that Driskill, a 52-year-old grandfather with a salt-and-pepper mustache and good-ol-boy twang, had served in the Air Force. Now, he oversaw county maintenance work performed by jail trustees. His worst brush with the law, he said, was a DWI in his 20s.

Holland, who was secretly (and legally) recording this exchange, occasionally teased at his intentions: He said he was part of a small crew of Rangers who focused on unsolved murders. “They put us together...and tell us that we can do whatever we want, as long as we solve cases,” he says to Driskill on the recording, which I obtained through a records request to the Parker County district attorney.

Once they arrived at the sheriff’s office, Holland offered Driskill coffee and reiterated that he wasn’t under arrest. The Ranger pulled out an image of a petite woman with dirty blonde hair.

“She don’t look familiar to me, period,” Driskill said. “I ain’t never seen her.”

The woman was Bobbie Sue Hill. Nearly a decade before this conversation, kids had stumbled upon her body in a creek bed under a bridge, less than a mile from Driskill’s home. Investigators pieced together that she was a 29-year-old mother of five whose husband had died in a car accident. She had been struggling with drug addiction and subsisting in a series of squalid motels near downtown Fort Worth. Hill’s boyfriend told investigators that he had seen a man drive off with her in a white van.

In their reports, the police signalled this could be the work of a serial killer. Fort Worth officers were already looking into the death of another sex worker, who entered a white van seven months prior and was also found in a creek bed. A third woman had accepted a ride from a man in a white van, and narrowly escaped after he fondled her at knifepoint. But despite these promising parallels, the leads dried up. “The lack of physical evidence in this case is frustrating,” one investigator wrote in a 2006 report.

In the small, fluorescent-lit room, Holland told Driskill that police had recorded his license plate near where Hill was taken and put his name on a list of men who “troll prostitutes.” But perhaps Driskill was just a good Samaritan who had given Hill a ride the night she was killed.

“I don’t ever remember giving someone a ride,” Driskill replied, “but that don’t mean I didn’t give someone a ride, either.”

Holland was lying about the license plate and the police list. This was perfectly legal — and effective, since Driskill rummaged through his memories and recalled driving through the area to visit his father, make car payments, and — perhaps — to bid on some home renovation work. He also remembered giving a woman he didn’t know a ride once, but not to Fort Worth. Eventually, he produced a hazy recollection of dropping someone off at a dollar store about a mile from where Hill was abducted.

In a recent interview at a prison in east Texas, Driskill told me that he didn’t believe he had witnessed a crime, but kept talking to the Ranger because he wanted to be helpful. Given his own work with jail detainees, he saw Holland as a fellow lawman.

But Holland interpreted the trickle of memories as a sign that Driskill was withholding information. In his genial drawl, the Ranger pointed out Driskill’s tendency to say, “Not that I know” and “Not that I can remember,” rather than just, “No.” He pulled out a picture of Hill’s corpse. “I think you’re afraid that you’re gonna get caught up in this deal,” he said, adding that if the DNA results he was awaiting matched Driskill, he’d be in trouble. “I don’t want you to be afraid,” the Ranger continued. “I want you to help me get the son of a bitch that did this.” But, he also said, “You’ve got to be honest with us, ‘cause if you’re not, then all of a sudden, I start looking at you as maybe the person who did this crime.”

That night, over barbecue, Driskill told his wife he was just a potential witness and had nothing to worry about. The next morning, he took a polygraph test. Many courts have deemed such tests unreliable, but police still use them in interrogations. His results indicated “deception,” and Holland dropped the previous day’s pretenses. “We already know it’s you,” he said.

Holland offered Driskill possible explanations: Perhaps he strangled Hill accidentally during sex. Or, had Hill and her boyfriend tried to rob the Air Force veteran, sending him into violent “military mode”? “You’re on the edge of the Grand Canyon,” Holland continued. “I’m asking you to take a jump off the edge. ... I’m going to hand you a parachute.” Then he asked Driskill to utter two words: “I’m sorry.”

“I’m sorry if I took somebody’s life, but I don’t think I did,” Driskill said as he began to cry.

But slowly, Driskill accepted Holland’s theories, confessing even as he repeated that he couldn’t remember any of it. Sheriff’s deputies arrested him at his home that evening.

In jail, having traded in his denim work clothes for black and white stripes, Driskill came to believe that his admissions made little sense. Still, fearing a skeptical jury, he pleaded no contest. He was sentenced to 15 years at a state prison, where he soon made contact with lawyers at the Innocence Project of Texas. Holland, for his part, would go on to become one of America’s most celebrated homicide detectives.

When officers pull off jaw-dropping successes in cold cases, their tactics are seldom questioned. But over the next year, as lawyers go to court on Driskill’s behalf, Holland’s work will likely face more public scrutiny than ever before.

Over the last year, I identified a dozen of Holland’s best-known cases. I used public record requests to gather more than 30 hours of audio and thousands of pages of reports and court testimony, and I shared excerpts with detectives, psychologists and other scholars. I sent findings and scholarly analysis by email and certified mail to both Holland and the Texas Department of Public Safety, which declined to authorize an on-the-record interview, as did the Parker County Sheriff’s Office. As I finished reporting, a state spokesperson said that Holland, who is in his early 50s, retired from the agency at the end of last year. I sent him a final request in late December to interview him post-retirement, and he did not agree to an on-record interview.

One of Holland’s key tactics — lying to suspects — remains common and protected by the courts. But in the search for Bobbie Sue Hill’s killer, the Ranger also used more contested methods, including hypnosis and hypothetical narrations of the crime. Altogether, his tactics demonstrate how far a detective can go without breaking the law, and how easy it is for the legal system to rely on a questionable confession. Even after years of high-profile exonerations, academic research on why innocent people are convicted, and attempts by judges and lawmakers to fix the problems, detectives continue to use techniques that are known to produce false confessions.

Across the country, fewer murders are getting solved year by year, and a growing backlog of cold cases — especially those without strong physical evidence like the Hill case — may incentivize detectives to take similar risks.

An elite class of state officers, the Texas Rangers are probably best known for inspiring a long-running TV series and the name of a professional baseball team. But they have been on the frontlines in the battle to resolve cold murder cases, working more than 160 of them since 2015, and closing more than 30. The Rangers — 166 strong as of last year — also police the Texas/Mexico border, uncover public corruption, and investigate deaths involving local law enforcement.

The Rangers’ two-century history is marred by episodes of hunting Black people who escaped slavery, massacring Tejano villagers, and harassing civil rights leaders. When the Rangers have faced scandal more recently, it’s usually about their homicide investigations. In the 1980s, they fed a man named Henry Lee Lucas details that allowed him to claim killings he could not have committed. Rangers also played roles in the wrongful convictions of two Black men, Clarence Brandley and Anthony Graves, who were exonerated from death row in 1990 and 2010, respectively.

Their current image blends ruggedness and sophistication. Doug Swanson, author of “Cult of Glory: The Bold and Brutal History of the Texas Rangers,” described it to me as “Scotland Yard in cowboy hats.”

In recent years, James Holland has come to embody this mystique. He rose to prominence in 2019 after obtaining 93 murder confessions from a California prisoner named Samuel Little. Over 700 hours, the pair shared grits and milkshakes while addressing each other as “Jimmy” and “Sammy.” The Los Angeles Times christened Holland “a serial killer whisperer of sorts,” while “60 Minutes” observed a “swagger that would make John Wayne envious.”

His journey from state highway patrol to pursuing serial killers is documented in a personnel file full of words like “flawless” and “gifted.” He grew up in suburban Chicago, according to the Los Angeles Times, and ended up in Texas for graduate school in criminal justice. He made his mark using traffic stops to search for drugs and guns. “As a trooper, I was extremely successful in criminal interdiction,” he once testified. “I found behaviors and language that indicated that someone was lying.”

Holland became a Ranger in 2008 and began working out of Decatur, a small town north of Fort Worth. According to department records, he has been involved in more than 200 investigations, showing a rare gift for talking to murder suspects. “This is kind of my calling, dealing with these really strange cases, the serial killers, the ritualistic killings,” he told “48 Hours” last year.

One of his first murder cases involved Jose Sarmiento, a suspect in a 2005 killing who moved to Mexico before police could arrest him. Holland got his phone number from his sister and persuaded him to fly back to Texas and confess. Sarmiento later claimed that the Ranger threatened to “put up some money to drug dealers” who would target his family. But in court Holland denied threatening Sarmiento: “Did I appeal to him emotionally, mentally? Absolutely. Was that coercive? No.”

Murder victims’ families have praised Holland for the way he seems personally moved by their pain. Gay Smither, whose daughter Laura was murdered by a serial killer named William Lewis Reece told me, “Jimmy Holland is my hero.” After speaking with Holland, Reece agreed to help investigators find the remains of his victims.

“I’ve worked hundreds of murders, put people on death row, done all kinds of things. I have seen people get probation, seen people get a couple years. And I’ve seen the other end of the spectrum,” Holland told Larry Driskill at one point. “People always ask me, ‘How do you sleep at night, knowing what you do?’ I always tell them this: I go to bed with a clear conscience … I give people the opportunity to tell the truth and to help themselves out … I’m not just throwing people in jail for the hell of it.”

Some of Holland’s biggest successes involved convincing serial killers already behind bars to give up their secrets. But when a suspect is free, Holland has used a different set of skills. Sometimes, he begins with a lie.

CHAPTER 3: THE WEAPON OF DECEPTIONThe Supreme Court paved the way for lying to suspects in a 1969 decision, but researchers are increasingly concerned about the practice. The National Registry of Exonerations has recorded more than 350 false confession cases since 1989, finding that police were accused of deception in a quarter of them. “The suspect comes to question their own sense of reality,” said Saul Kassin, a John Jay College of Criminal Justice psychologist who has studied confessions for decades. “This isn’t about being a bleeding heart. Usually, the real perp got away and killed others. That’s on your shoulders if you obtained a false confession.”

Last year, lawmakers in Illinois and Oregon banned the deception of juvenile suspects, based on the idea that they are especially vulnerable. The Innocence Project (which is not related to the group representing Driskill) said lawmakers in a half dozen other states have expressed interest in pursuing similar bans, and some may cover adult suspects.

Lying is one of several tactics that Holland’s approach shares with the Reid Technique, an interrogation method that has dominated the field since it emerged 70 years ago, replacing beatings and torture. The technique is so influential it has shaped a generation of television and movies — think claustrophobic rooms and smooth-talking detectives. But even without violence, researchers believe that it’s still too easy to manipulate an innocent person into confessing.

John E. Reid and Associates, the company that pioneered the technique, insists that false confessions arise when detectives violate their training. Lying “should probably be a last resort,” the company’s president, Joseph Buckley, told me in a recent interview. Still, he says it would be wrong to ban the practice entirely, arguing that false confessions usually involve additional coercive tactics. Of the 12 cases I reviewed with the help of forensic experts, Holland has attempted to deceive at least seven suspects.

Back in 2005, investigators combed the area around Bobbie Sue Hill’s body and collected four fresh cigarette butts. One of them carried human DNA, and eight years later, a crime lab matched it to a Dallas woman. She denied knowing about the murder, but described a man she dated in 2005 who had choked her during sex. The Parker County Sheriff’s Office enlisted Holland to interview this man, who flatly denied any knowledge of the crime. (Given their limited role in the case, we have chosen not to name the woman and man. The man did not respond to a letter sent to prison, where he is serving time for drug possession.)

Now that Holland was involved, he decided to interview Timothy Dawson, an organic chemist who became a suspect in 2005, after reporting his mother’s white van stolen. He had a record of violent crime and had spent time with people on the margins, including sex workers. According to prosecutors’ records, Dawson’s wife told a detective he’d been “extremely paranoid” around the time of Hill’s death.

Holland showed Dawson a picture of Hill, and he admitted she looked familiar. Then the Ranger said the victim’s brand of hair dye was found in his van. There is no indication in Holland’s report that this was true.

In a recent phone interview, Dawson unequivocally denied involvement and said he was put off by Holland’s swagger. “He came in big doggin’ it. I had the aha reaction. ... He wasn’t trying to solve this crime. He was trying to hang me!” He remembers telling the Ranger, “If you want to solve the case so bad, you take the fucking charge.”

According to Holland’s later court testimony, the Parker County Sheriff’s Office thought Dawson was a “very good suspect,” but the Ranger said they had the wrong man. Holland had already begun searching for a new suspect, by less common means.

In October 2014, James Holland tracked down the only person who reported seeing the man who drove off with Bobbie Sue Hill: her boyfriend, Michael Harden. Tall and languorous, he was known to meander with a cane down the streets of Fort Worth’s skid row. Holland found him at the city’s downtown jail, where he was facing drug charges.

Harden had met Hill roughly a year before her death. They lived in motels, supporting their drug habits through her sex work and his odd maintenance jobs. One night, they stood outside a gas station, pretending to use a pay phone so she could advertise to johns. Harden saw a white van drive up and down the street numerous times. He felt suspicious, and when the van finally pulled up, he told Hill not to go.

“That’s OK,” he recalled her saying. “I’ve got it.”

Harden told Hill to bring the man to a side street. When he walked over to check on them, Harden saw through a foggy window that the man had removed his shirt. “His eyes got big,” Harden told me during an interview. “He put his glasses on, he realized it was me, and then he threw that fucker into gear.” After Hill’s body was found, Harden blamed himself for letting her go. He also wondered if it was a hate crime, since she was a White woman and Harden was a Black man.

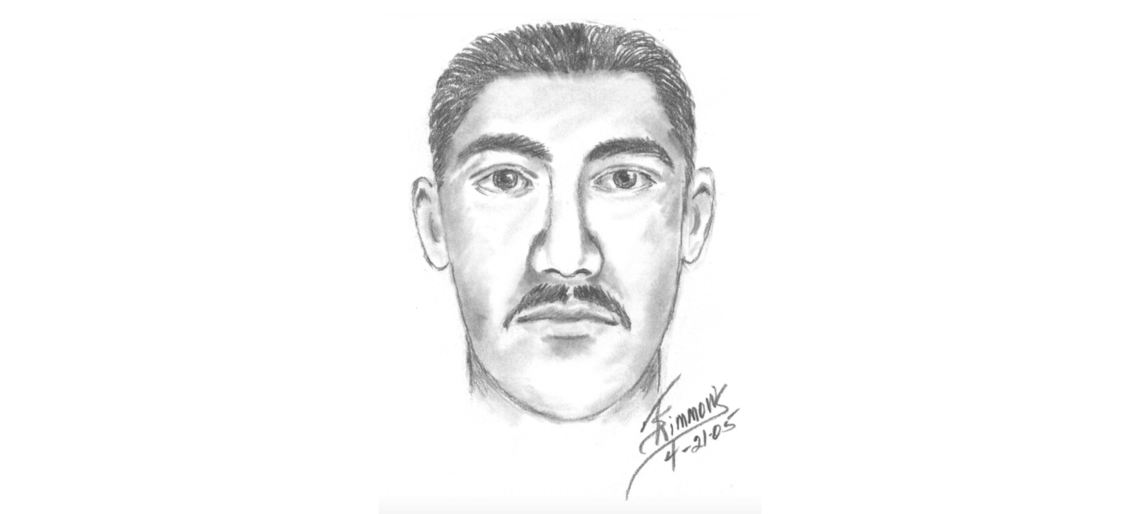

The police produced a sketch of the driver based on Harden’s description, which showed a wide, boxy face, prominent eyebrows and a thin mustache. Records do not indicate that it led to any suspects.

Nine years later, Holland asked Harden to try again, with some “weird” memory exercises. Holland turned off the lights, and asked Harden to close his eyes, picture details like the victim’s hair, and summon the sounds of their friends’ voices. He then directed him to replay his memories in reverse chronology, and to imagine himself at the top of a telephone pole, looking down at the van.

“Did you see a mustache?” Holland asked about the driver.

“No, he didn’t have a mustache,” Harden said.

Holland was using elements of the “cognitive interview,” which was developed several decades ago by American psychologists who wanted to help police get more useful information from crime witnesses and victims. (One of these psychologists, Ronald Fisher, read Holland and Harden’s exchange and said the Ranger did a generally good job.) When detectives use this method — which has not faced the same criticisms as the Reid Technique — they ask witnesses to revisit the entire context of the events, including smells and sounds.

When Harden opened his eyes, another investigator showed him photographs of faces. Harden pointed to one and said he was 70% certain it was the driver. The Ranger then showed him pictures of vans. Harden’s description of the vehicle changed as well, from a minivan with side windows to a windowless work van.

It is impossible to know precisely why Harden’s memories changed, although Christian Meissner, who studies cognitive interviewing, said it was possible Holland had contaminated his memory by showing him pictures of faces and vans.

Cognitive interviewing emerged at a time when judges and scientists were increasingly skeptical of another new and popular police technique: forensic hypnosis. Detectives argued that hypnosis improved recall, but psychologists were concerned it could make a witness overly confident about a mistaken memory. Throughout the 1980s, many courts banned testimony from witnesses who had been hypnotized, meaning police could no longer use it in numerous states.

But Texas remained a hub for forensic hypnosis. In 2020, The Dallas Morning News found that the Texas Rangers were among the last detectives nationwide to regularly use the method. Last year, Texas Gov. Greg Abbott vetoed a bill to ban testimony following hypnosis, even as the Texas Department of Public Safety formally ended its hypnosis program. The department did not, however, express doubt about previous cases solved with the practice.

And the program was still in full swing in 2014, when Harden agreed to be hypnotized. A week later, he had a session at the jail with another Ranger, Victor Patton, who told Harden to count backwards from 100, imagine grains of sand on top of his head, and describe the abductor’s face.

In a recent interview, Patton told me hypnosis was usually a last resort, and only useful if new claims could be corroborated. “It’s almost permission for people to tell you something they suppressed, or don’t want to talk about,” he said.

After the session, a forensic artist interviewed Harden and produced a strikingly different sketch, featuring wire-rimmed glasses, a flat-top haircut with shaved sides, and a darkened area above the lip that could suggest a faint mustache.

Then, to account for the passage of time, the sketch artist produced an “aged” version, with a few more wrinkles and more pronounced jowls and smile lines.

When I found Harden at a motel in Fort Worth this past April, he did not clearly remember the hypnosis session. But he was skeptical. “Whatever the fuck I saw when I wasn’t hypnotized is going to be what the fuck I saw when I [was] hypnotized,” he said. When I showed him the two sketches — produced in 2005 and 2014 by two different artists — he said the latter more closely reflected his memory.

And yet now — seven years after the hypnosis session, and 16 years after he actually saw the face — Harden told me he did remember a mustache, after all.

I described the disappearance and reappearance of the mustache to Gary Wells, an Iowa State University psychologist who has studied composite sketches since the 1980s. Although sketches have helped solve numerous crimes, Wells said that even in ideal conditions, it’s difficult for people to accurately describe faces because we remember them holistically and not feature-by-feature. And “memory doesn’t get better with time,” Wells said of the nine-year period between Harden’s sketches. He also noted that the witness's recall could have been contaminated by the thousands of faces he’d seen since the crime. “Any change is a big flag.”

The Innocence Project has found that nearly 70% of people freed through DNA testing were convicted, in part, due to an eyewitness misidentifying them. In a quarter of these cases, a composite sketch was involved. Errors grow more likely when the witness and perpetrator are of different races, as they were in Harden’s case.

Two months after Harden was hypnotized, the sheriff’s office put out a press release showing a full-size, windowless white van, the “age-progressed” sketch, and James Holland’s phone number. Within days, the Ranger received a call from a local pawn shop owner who was sure the image depicted his longtime customer Larry Driskill.

CHAPTER 5: HYPOTHETICALLY SPEAKINGAmong the people who thought the sketch did not particularly resemble Larry Driskill was Larry Driskill. “I thought, Does that really look like me?” he told me.

During the second day of questioning, Holland shifted into a tactic less routine than lying: the hypothetical.

He told Driskill (truthfully) that Michael Harden, the victim’s boyfriend, had undergone hypnosis, but then said (falsely) that Harden admitted to trying to rob him. Based on this lie, Holland asked Driskill to describe the attempt without committing to it.

“Start with that… Just say, ‘Hypothetically, I was down there, and they were trying to rob me,’” Holland said.

“That’s admitting to something that I don’t even know happened,” Driskill replied.

“No it’s not,” Holland said. “When you say ‘hypothetically,’ it’s not locking you into anything.”

Holland offered Driskill chewing tobacco, and as they spat into cups, the suspect dropped his resistance. His hypothetical statements slowly became an admission.

“I was giving her a ride to the house and there was a confrontation in the vehicle,” Driskill said. “I think she was trying to take my billfold from me, and I went to defend myself, to try to push her out of the car, and my hands went from her chest to her neck. And I guess I choked her down.”

“You guess or you did?” Holland asked.

“I did. I did choke her down then. ...I guess my military [training] kicked in when she tried to assault me.”

In a later version, Driskill said that he and Hill were having sex when she reached for his wallet. But he also continued to say he couldn’t remember any of it and broke down in tears a second time.

Writing to me from prison last summer, Driskill summoned a seemingly unrelated memory. While he was in the U.S. Air Force, a jet exploded at a training base, and he was ordered to handle soldiers’ remains. “It made me sick when [Holland] showed me pictures of the dead girl, and my mind took me back to that day tagging body parts,” he wrote. He believes post-traumatic stress disorder made him receptive to Holland’s argument that he snapped into “military mode” and blacked out.

After Driskill said he killed Hill, he and Holland discussed how he might have disposed of her. At the Ranger’s urging, he drew several pictures of her corpse folded into trash bags, depicting how he taped them shut. Driskill told me these drawings were guesses based on crime scene photos that Holland showed to him earlier. But Holland told him he was corroborating information only the killer would know.

Later on, Driskill contradicted some known facts, saying the victim asked him for a ride outside a 7-Eleven almost a mile from where she was taken. Holland asked if he was certain. He said he wasn’t, and then mentioned a cross street even further away from the abduction site.

Without more evidence, it is impossible to know whether Driskill gave a false confession, lied to Holland about his inability to remember, or lied to me about his innocence. But several researchers who examined excerpts from Driskill’s interrogation transcript identified red flags.

It’s well known that false confessions can arise from stress. “I was hungry, tired, scared, nervous, and just wanted to do whatever it took so I could go home,” Driskill wrote in a July letter. “I was pretty desperate to get out of that room, but the Ranger was always between me and the door.”

But Driskill also describes a momentary belief in his guilt. “I’m sitting there thinking, Could I really do this?,” he told me. “Subconsciously, he had me thinking that I did it.”

His temporary belief in his guilt also squares with academic findings on just how easy it can be to implant memories, especially when hypotheticals are involved. In a 2015 study, Canadian researchers used suggestive memory exercises to convince college students that they had committed fictional thefts and assaults. The researchers concluded, “What something could have been like can turn into elements of what it would have been like, which can become elements of what it was like.”

After reading interrogation excerpts, University of San Francisco law professor Richard Leo noted the moments when Holland pushed Driskill to claim self defense. Some scholars call this “minimization,” while some detectives call it finding “the out.” The problem, experts say, is that minimization can skirt dangerously close to a promise of a lighter sentence, which can further convince innocent people that confessing is their only way out.

In a recent email, Parker County district attorney Jeffrey Swain said Driskill’s confession was credible, despite the factual errors. He was struck by how Driskill correctly described how the victim’s body was found, even when the Ranger pressed him with alternative possibilities. The prosecutor praised Holland’s patience and skill, but acknowledged that prosecutors faced an uphill battle without physical evidence. “While we are confident that Mr. Driskill murdered Bobbie Sue Hill,” he wrote, “that doesn’t mean that the case was an ideal or easy one for a jury.”

CHAPTER 6: THE POWER OF FATIGUETwo weeks after Driskill’s arrest, Holland traveled north to Gainesville, a town of 16,000 where deputies had reopened the unsolved 1997 murder of Shebaniah Sarah Dougherty. The 20-year-old had disappeared after working her shift at a video store, and people found her body while walking in a wooded area. A key suspect had died in a car accident before detectives could find enough evidence to arrest him.

In April 2015, Holland drove to the workplace of Dougherty’s friend Christopher Ax. The Ranger learned that their families were close, that they had once gone on a date, and that he regularly visited her at the video store. Ax explained that he’d left town after a police officer suggested that he could be a suspect.

The Ranger called Ax numerous times over five weeks and told him — falsely — that his DNA had been on Dougherty's socks and shoes. Over the course of these conversations, Ax recalled seeing the previous suspect at the video store and said the man had hit on his friend. He also remembered eating pizza with Dougherty at her job then going to his house to hang out, but 18 years later he couldn’t remember if this happened the day she was killed.

Using elements of the cognitive interview, Holland told Ax to close his eyes and focus on the flavor of the pizza they’d shared. Eventually, Ax said that the night she died, Dougherty was at his house watching TV as he rubbed her feet.

“Almost every fiber of me was saying, Stay the hell away from this guy,” Ax told me recently. “But my family was saying, ‘You need to go help him,’ and I kind of took her death personally. I really wanted to help get closure for [her] family.” Ax also admired Holland’s job title; as a teenager he had aspired to be a Ranger himself.

Against the advice of a lawyer, Ax agreed to take a polygraph. He failed, and Holland began to alternate between accusations (“You were there when it happened.”) and offers to help (“I want to prove definitively that you didn’t do this.”)

Ax failed the test around 9 p.m. Around 2 a.m. in response to Holland’s questions about how, hypothetically, he would have killed the victim, Ax described accidentally choking Dougherty, but added that he didn’t know if this was a memory or the “vivid imagination of a tired mind.” Holland secured an arrest warrant a few days later. At the jail, Ax repeatedly said he had no memory of killing anyone, but Holland encouraged him to believe he had done so in self defense.

The recording of their exchange, obtained from the Cooke County district attorney’s office, is more than eight hours long. Ax told me he remembers little beyond exhaustion and disorientation. At times, he believed he killed his friend: “He’s a Ranger — if he says it’s true, I guess it’s true,” Ax said. But at other moments, he was certain of his innocence and seemed to feel hopeless about his ability to prove it. At one point, Ax asked Holland to shoot him.

Early in the evening, Ax suggested they visit the area where Dougherty’s body was found. When they entered the barn near the site, Ax said he remembered the walls. A story emerged, with the Ranger and the suspect each supplying connective tissue: Dougherty made a sexual advance in the car, Ax rejected her, and she hanged herself. “I remember the arms were down.” Ax told Holland. “I think I took her down.”

Like Driskill, Ax had served in the military, and was traumatized by a fellow soldier’s death — a suicide by hanging. He too wondered if the police interrogation revived this stress, contributing to the blur between memory and invention.

Back at the sheriff’s office, they ate pizza, which Holland suggested might jog Ax’s memory. As they began discussing a green rope found around Dougherty’s neck, Ax threw up. Holland hinted this was a sign of guilt. (Ax says now he was just sick.) They talked through a scene of Dougherty attacking him with the rope. “If she comes at you with that thing and starts trying to wrap it around your neck and you’re pushing it off and it ends up around hers...” Holland said in the recording.

Later, Ax said, “I don’t remember every detail of it, but I can see it...I wish like hell I couldn’t.”

After 20 months in jail, Ax was released on bond. As the case crept towards trial, Cooke County prosecutors sent the victim’s clothing out for DNA testing, which had improved in the years since the crime. The results indicated a high probability that the DNA belonged to the original suspect, not Ax. In September 2018, the district attorney dropped charges, stating in a press release, “We cannot blindly seek convictions or close our eyes to evidence that points in a different direction than we are heading.”

Eric Erlandson, a prosecutor who worked on the case, was more cautious. “I listened to every second of audio on that case and I was convinced he did it,” he told me. The DNA sample was small and left room for error.

Ax maintains his innocence and told me many people in his town are still convinced of his guilt, which makes it difficult to make friends, date, or find steady work. He said several loved ones died while he was in jail. Mostly, he blames Holland.“I don’t hate many people in this world, but he is one of them,” Ax said. He predicted that Holland “is going to do this to another innocent person.”

No DNA results came back to aid Larry Driskill’s defense. From 2015 to 2017, Parker County law enforcement worked to build a case around his confession. A few days after his arrest, the sheriff’s office discovered that in 2005 he had worked for a casino party company, and sometimes drove a white cargo van. They seized the van. Inside they found black duct tape, which they believed matched the kind of tape found with the victim’s body 10 years earlier.

While Driskill awaited trial, a fellow detainee named Jesse Carrington came forward, claiming Driskill had confessed to him on the recreation yard. Driskill denies the encounter. Carrington, like many jailhouse informants, was not a disinterested party: In his case file I found an email from a prosecutor, who promised to reduce his sentence for theft, in exchange for testimony against Driskill. When I reached Carrington via Facebook Messenger, he stood by his story but told me he wouldn’t have testified to it in court because he “didn’t know enough about his situation.” Driskill didn’t know about the informant’s hesitation. As far as he was concerned, the jury would hear that he had admitted to murder not once, but twice.

Driskill's lawyer tried* to get his confession to Holland barred from trial because he had not known he was a suspect. The lawyer also noted gaps in the interrogation recordings, caused by equipment malfunctions. But before a judge could rule, Driskill pleaded no contest to the murder charge. He is due to be released in 2030, although he will be eligible for parole this summer. “I feel like I lost everything,” he told me. He and his wife are divorcing. His adult children don’t visit him. His mother used to make the four-hour drive to his prison, but eventually he told her not to bother.

When I asked him about James Holland, Driskill addressed him directly. “You’ve ruined my life. Should you be able to walk around free, screwing other peoples’ lives up?” At other moments, he was more forgiving: “I don’t hate him. I’m upset with him — but I’m not mad at him. I don’t want revenge. That’s in God’s hands.”

Lawyers from the Innocence Project of Texas, who declined to discuss the case, are still investigating. Swain, the prosecutor, said he agreed to let them send items to a lab for DNA testing. “In our view, none of these items are the type of things that would change how a jury would have viewed the case,” he told me, expressing frustration that Driskill waited until after he “received the benefit of a plea agreement” to declare his innocence.

At the same time, the Rangers have not technically closed Driskill’s case. They are still trying to solve the murder of Trina Nash, a sex worker last seen entering a white van in Fort Worth, seven months before Hill’s death. When I requested records, I learned that the Rangers consolidated the two cases under a single “report number,” suggesting they may pursue Driskill for Nash’s death as well.

When Driskill received his prison sentence, Bobbie Sue Hill’s family gathered in the courtroom to watch. “My mom’s short life enriched the lives of so many people,” Hill’s oldest daughter, Ashley Lor, said in an official victim impact statement. “She’ll be loved and missed forever.”

They had spent 12 years waiting for this moment, but the heartbreak had begun well before her death. They remembered a rambunctious child, who had a loving relationship with her brother and a contentious one with their single mother. She dropped out of high school and married her boyfriend. By the time she was 27, they had five children. “Her kids were her life,” said her cousin Cindy Elmquist during a recent phone interview. (Her children, as well as a sibling, did not respond to requests for interviews.)

In October 2003, Hill’s husband died in a car accident. His family took in the kids, and she began disappearing for days at a time. Elmquist would drive over to East Lancaster to look for her. “I saw her sitting on a curb and I barely recognized her. Her face looked so weathered,” she said. “We would say, 'Girl you need to get home, get off them streets. Something is going to happen to you.’”

Hill’s aunt Judy Tatum told me she would help Hill pay for places to stay and deliver food when she’d complain of hunger. “She saw her flaws and didn't want to pass it on to her kids,” another cousin, Billy Day Jr., wrote to me. He remembered her crying as they used drugs together. “She didn't believe she could be what her kids deserved. So she stayed away, seeking any means to numb her senses, memories, and dreams.”

Several weeks before Hill disappeared, she indicated to her oldest daughter that she was ready to return home. Then her mugshot flashed across the local news. “Everyone thought it was never going to get solved, and that nobody cared,” Elmquist said. When the Texas Ranger came along, they were thrilled. Still, they were bothered that Hill’s public image would be defined by her worst moments. They wanted the world to know there was so much more to her.

If Larry Driskill’s team does convince a court to free him, it may tarnish the reputation of Holland, and present a public relations problem for the Texas Rangers. But it will be Hill’s family that has to return to not knowing the identity of the person who killed her, or whether that person is still out there.

Edited by Akiba Solomon. Design and Illustrations by Bo-Won Keum. Photo editing by Celina Fang. Development by Katie Park. Audio editing by Marci Suela.

Picture of Bobbie Sue Hill adapted from a driver’s license photo obtained from the Parker County District Attorney’s Office.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly described Larry Driskill’s trial lawyer. He was appointed by the court, rather than hired by the defendant.

No comments:

Post a Comment